Читать книгу Barry Sheene 1950–2003: The Biography - Stuart Barker - Страница 9

CHAPTER 3 PLAYBOY

Оглавление‘Two women sharing my bed was old hat as far as I was concerned.’

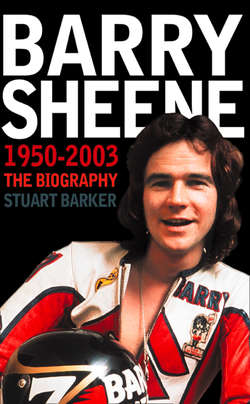

It’s fair to say that there is no long-standing tradition of motorcycle racers being pin-ups, heart-throbs, playboys or style gurus, but Barry Sheene was all of these things and a whole lot more, besides being a phenomenally successful racer. Ever since his first sexual dalliance over a pool table in the crypt of a London church, Barry never left anyone in any doubt about his sexual orientations. Certainly wealth, fame and the perceived glamour of his chosen profession helped considerably in his conquests of the opposite sex, but his boyish good looks and easy charm were already in place long before any material success.

Sheene was born with a natural blond streak in his otherwise brown hair which, he claimed, was a result of his mother having received a nasty shock during pregnancy when a child walked out in front of her car. According to Sheene, who presumably got the story from his mother, the incident was enough to leave a birthmark on his head which in turn caused the blond streak to grow from it; he related this story many times to prove he was not dyeing it and hence ‘not turning into a pouffo’. It seems Sheene was destined to stand out from the crowd even before he was born. Blond streak aside, the long, flowing locks were all his own doing, together with overgrown sideburns a fashion ‘must’ in the seventies. ‘Having your hair cut in the seventies,’ he observed, ‘was like having your legs amputated. It just wasn’t on.’

Sheene was not built like an athlete, but his frame seemed to serve him well enough when it came to the fairer sex, and what he lacked in the Adonis physique stakes he more than made up for with his ready wit and devil-may-care attitude. In 1973, his looks were deemed worthy of an appearance in Vogue magazine, an accolade of which no bike racer before or since can boast. The man behind the lens was none other than David Bailey, one of England’s most celebrated photographers, more used to working with Mick Jagger, the Beatles, Salvador Dali and Jack Nicholson than with motorcycle racers. The Vogue job wasn’t Sheene’s only modelling stint, either; his other assignments included posing in a pair of underpants alongside a semi-naked woman in the Sun – again, not the most traditional extra-curricular activity for a bike racer, a point that was not lost on Sheene. ‘I reckon I finally destroyed the popular concept of a biker when I was pictured in the Sun. This wasn’t quite what traditional bike enthusiasts had come to expect, but I’m sure it helped to undermine the myth that all those who rode motorcycles are dumb, dirty and definitely undesirable.’ Sheene even went on to have his own weekly column in the Sun in the seventies, which gave him a much coveted mouthpiece in the country’s biggest-selling newspaper.

Image was always important for Sheene, and his greatest role model was Bill Ivy, whom he had known and admired since childhood, as he admitted in an interview for Duke Video in 1993. ‘I suppose one of the biggest influences when I’d just started racing was Bill Ivy because [he] used to race for my dad and was a good mate of mine and I loved his lifestyle. I mean, he was always surrounded by crumpet, all young ladies. I suppose I sort of modelled myself on Bill in that he always used to dress the way he pleased and his lifestyle was a lot of fun, and the woman side of it was the bit I envied the most.’ Sheene’s former rival Mick Grant witnessed Barry’s dealings with the media first-hand and reckoned he played up this playboy image. ‘He was just very good with the media. He was probably better with the media than he was at riding, and he was okay at riding.’

Anything Barry did to improve his own personal standing and image usually seemed to have a positive effect on motorcycle racing in general. He might have had to get rid of the saucy patches he wore on his leathers (‘Happiness is a tight pussy’; ‘I’ll make you an offer you can’t refuse’) once he became famous, but he was still capable of attracting attention to himself as a rider. White leathers when most others wore black, the colourful Donald Duck motif on the helmet, the gimmick of making a victory V sign whenever he won a race (which signified victory to the spectators while appearing as something very different to the riders behind him), a caravan to take girls back to rather than an oil-stained van – all these things helped Barry’s personal pulling power as well as the overall image of the sport.

The caravan was introduced during the 1971 season, and while Sheene himself claimed to have bought it on hire purchase, his brother-in-law Paul Smart said that Barry ‘blew half his money on it’. However it was paid for, it was money well spent, as Smart explained: ‘The only thing he was world champion at was sex. In every country, there used to be a hell of a competition for the girls in the paddock. Barry won, of course. The thing is, he’d never give up. He could have three blow-outs but he’d just keep going until he scored. The caravan body eventually fell off the chassis.’ Years later, Sheene admitted this to me, and the caravan falling apart led to another problem, as he explained. ‘As I was welding [the chassis] I lost the St Christopher my mum and dad had given me for luck. At the very next race [the 1972 Imola GP], my bike seized, threw me up the road and punctured my stomach, so my mum and dad bought me another St Christopher.’

The more polished Barry’s image became, the more ‘crumpet’ he could pull. Sheene’s first serious girlfriend was Lesley Shepherd, whom he met in 1967 when he was just 17. They dated for the next seven years but split in 1974 after a relationship which, by Barry’s own admission, was not quite monogamous. He openly confessed to seeing other girls during his foreign travels of the period, some of whom he’d met on the dancefloor. Like most youngsters who lived through the seventies, Barry Sheene loved his disco dancing. It wasn’t so much for the physical benefits that could be gained from all that strutting under a sparkling glitter ball as the fact that it was an easy way to meet girls – and when it came to that Sheene never missed a trick. When he was recuperating from injuries sustained at Mallory Park and aggravated later at Cadwell Park in 1975, the biggest frustration for Sheene wasn’t his inability to ride a bike, it was not being able to dance: ‘[My] inability to get on that dancefloor made me even more determined to get back to peak fitness as quickly as was humanly possible.’

As usual, Sheene only wanted the best and most exclusive when it came to nightclubs, and his annual membership of Tramp near Trafalgar Square was, as far as he was concerned, £30 well spent. There he could mix with fellow celebrities and, naturally, a bevy of gorgeous models. Barry was never shy about boasting of his female conquests, once professing to be every bit George Best’s equal when it came to hitting it off with top models – and in the seventies when he was at his peak, keeping up with Best was no mean feat. The evidence would certainly seem to support Barry’s claim when one considers that it wasn’t unusual for him to have three women on the go at any one time; he often had to juggle them around to avoid potentially embarrassing double-bookings on the same night. ‘As far as women went,’ he said, ‘I was the man for all seasons. A different girl each night was my regular pattern. There were even weeks when I would be saying goodbye to one young lady, immediately chatting another up on the phone and eyeing the clock to see how soon the third would be arriving.’ Of course, sometimes the double-bookings were intentional. ‘I had tried everything that I had read about and a whole lot more besides. Two women sharing my bed was old hat as far as I was concerned.’ Even when he was fit enough to be at a race track rather than recuperating from injury, Sheene, unlike many other top sportsmen, refused to observe the energy-saving, no-sex rule on the evening or morning before an event. If Barry felt like ‘getting his leg over’, an inconvenience like a motorcycle race wasn’t going to stop him.

During his recovery period in 1975, Sheene found that he had a lot of spare time on his hands, and the most natural way he could think of to fill it was to chase girls. The fact that at the time he was sharing the London home of his great friend and aristocratic socialite Piers Weld Forrester, who was probably most famous for his association with Princess Anne before her marriage to Captain Mark Phillips, made for rich pickings on the female front. Forrester and Sheene received countless invitations to high-society parties and Sheene confessed that the women he met were major contributors to his recuperation process. ‘My favourite part of the rehabilitation process was trying to bed as many women as possible,’ he said. Chas Mortimer, himself the product of a public-school education, admired the way Sheene was able to break down social barriers and become accepted by the aristocracy. ‘There were quite a few people from the aristocracy in those days who used to be associated with racing. Barry would always be up at the Piers Forrester parties in London and he was a great one for hob-nobbing with the landed gentry, and you know what the landed gentry are like when they meet a cockney who appeals to them. All of a sudden, like Michael Caine in the film world, you become socially acceptable, whereas in other spheres of life cockney-ism might not be acceptable for them. Motorcycling tended to be a working-man’s sport and car racing tended to be the landed gentry’s kind of sport. Barry was able to transcend the social barriers, which are very strong in the UK, stronger than anywhere else in the world probably.’

Forrester’s death during a minor bike race at Brands Hatch in 1977 devastated Barry; it was yet another reminder of how dangerous motorcycle racing was in the seventies. According to Mortimer, the dangers of the sport even affected how close some riders got to one another. ‘Barry and I have always got on quite well together, but we were never the best of buddies. We were from the same generation and it was difficult in those days because a lot of people were getting killed and you didn’t want to make too much of a mate of someone in case they got wiped out.’

During the same recovery period, Barry also treated himself to the ultimate status symbol: a Rolls Royce Silver Shadow complete with personalized registration plate, 4 BSR. Racing rival Phil Read already had one, which might have been reason enough for Sheene to follow suit, but he always claimed he was swayed by Rolls Royce’s reputation for reliability than by the status-symbol trip. The only probable reason Barry didn’t buy a Roller any earlier than he did was because he’d lost his driving licence for 18 months for drink driving. By his own admission he’d had ‘a few rounds of drinks’ in King’s Lynn, Norfolk, with a friend before being involved in an accident while driving home. Barry claimed he got slivers of glass in his eyes from the collision and went straight home to rinse them out, only to find a police car awaiting him. Barry later appeared at King’s Lynn Crown Court protesting that he had fully intended to call the police to report the incident as soon as he had washed the glass out of his eyes, but his licence was suspended for a year with another six months added on as part of the points totting-up system (he already had various other minor offences on his licence). Sheene was also required to take another driving test in order to regain his licence, which he eventually did, but for one and a half years he needed to be driven everywhere he went, except on the Continent, where he drove himself.

The King’s Lynn incident wasn’t the only occasion when Barry found himself with a spot of car trouble. He very nearly drowned after some hire-car antics in Italy in 1974 went overboard – quite literally. Sheene was fooling around in the Fiat with fellow racers Kenny Roberts and Gene Romero, experimenting with a somewhat unorthodox driving method: Roberts took the wheel, Romero operated the foot pedals and Sheene applied liberal and erratic doses of handbrake at his leisure. The result was predictable, even if the location was a little unusual: the trio ended up in a canal, the Fiat turned upside down and sinking fast. Romero got out relatively easily but Barry was temporarily snagged up in the very handbrake he had so recently been abusing. He, too, eventually got out, but he still had to rescue Roberts who was calling for help, trapped in the quickly submerging vehicle.

On another occasion, again in Imola, Sheene parked his hire car in the town square unaware that the market was due to take place the following morning. When he returned to the car he found stalls all around it, one in particular utilizing the bonnet. Oblivious to the jeers of the traders who were convinced that Sheene was going nowhere until the market was over, Barry simply climbed into the car, floored the accelerator and smashed through the stalls. Dumbfounded pedestrians could well have been forgiven for thinking a James Bond movie was being filmed in their home town. After all, the two did have a certain number in common.

Sheene’s laddish behaviour might have continued unchecked, but his womanizing days came to an abrupt end in late 1975 when he met Stephanie McLean, a 22-year-old glamour model, former Playboy bunny girl and star of the classic Old Spice surfing advert. Stephanie was at the time married to top glamour photographer Clive McLean, with whom she had a five-year-old son, Roman. Such was Sheene’s standing as a national celebrity in early 1976 that a picture of him stepping out on town with Stephanie made the front page of the Sun – a somewhat dubious honour reserved for ‘class A’ celebrities and a sure sign that Barry was now a household name, in Britain at least.

Barry first met Stephanie at Tramp while he was still on crutches. She had seen the Thames Television documentary surrounding his Daytona crash and asked to borrow his leathers for an October modelling assignment which Sheene himself attended. He was instantly smitten with Stephanie and appeared to give up his womanizing almost overnight, even if such a drastic change of lifestyle threatened his image. ‘I couldn’t give a monkeys about the bachelor playboy image being ruined,’ he said. ‘The image was only there because that’s what I was like.’ Sheene later admitted that settling down to a one-woman relationship wasn’t as difficult as he thought, although his very words seemed tinted with an air of nostalgia for good times past. ‘With a massive list of conquests behind me, I knew I had completed all the running around I had ever wanted,’ he said. ‘Since settling down to a steady relationship with Steph, I have never once yearned for those wild times: the days of the paddock groupies; the passionate notes waiting for me when I returned to hotels after a race; the women who simply wanted to experience sex with a celebrity. All that is behind me now.’

Meeting Steph might have marked the end of Sheene’s direct involvement with other women, but it certainly didn’t stop other girls swooning over him, or even rowing over him. At Cadwell Park in 1976, two girls had a stand-up fight outside Barry’s caravan as they fought to get near him for his autograph, and on another occasion a girl approached Barry wielding a pair of scissors in a desperate attempt to snatch a lock of his hair. It was the kind of behaviour previously reserved for rock stars, and it prompted the media to refer to Sheene as a rock star on a bike.

Barry certainly lived up to the tag in 1979 while staying in a five-star hotel before that year’s French Grand Prix. Trying to get a good night’s sleep before the race, Barry became increasingly annoyed with the band playing at full volume downstairs. When a phone call to the manager had no effect, in protest Barry emptied the contents of his mini-bar over the balcony near where the band was playing, but again to no avail. When another call to the manager failed to subdue the noise, Sheene performed the classic rock star attention-grabber: the 26-inch colour television was lobbed out of the window and it shattered into a million pieces, loudly enough to be heard over and above the offending band. They stopped playing straight away and Barry got his peaceful night’s sleep. In fact, he got more than that. Upon returning to the hotel after the race, he found that a new television had been placed in the room along with an ice bucket and two bottles of champagne by way of apology on the management’s behalf for permitting so much noise at the dance.

Despite his attachment to Stephanie, Barry’s eye for the ladies did not go unnoticed by the organizers of the 1977 Miss World competition. In an era when the contest was a worldwide must-see television event, Barry was asked to cast his expert eye over the contestants. After Mary Stavin (who would later date the aforementioned George Best) won the event, the press asked Barry to dance with her while they took some pictures. Stephanie at that point promptly left the building, leading observers to believe she was in a jealous rage and had stormed out on Barry. According to Sheene, however, Steph was just tired of all the media attention and had decided to leave for a bit of peace and quiet. The press didn’t buy it, but either way it meant more mainstream publicity for Barry as most major newspapers ran a story on the incident the following day.

As infatuated as Sheene was with Steph, and as much as he claimed to have ‘retired’ from his sexually rapacious lifestyle, he still found it impossible to let go of his bachelor status when push came to shove in 1976. Speaking to Thames Video in 1990 for The Barry Sheene Story, he explained, ‘We were due to get married in 1976 and everything was planned. We were living in Putney, and three days before we were due to get married I was lying in bed that night and I thought, “I can’t get married. I’m scared to death of getting married, I really can’t.” I said to Steph, “Look, I can’t get married. I can’t do it. I love you, I adore you, you’re the best thing since sliced bread, but I don’t want to get married.” Obviously for Steph it was quite upsetting, you know, because she thought, “Oh, Christ, what’s going to happen now? I’ve split up with my husband, got a divorce, and now he doesn’t want to marry me.” You know, why wouldn’t I want to marry her? Obviously [it looked like I] didn’t want to be with her but that wasn’t the truth, I was just scared to death of getting married. So it was a bit of an uneasy period for the next couple of months.’

Sheene did remarkably well to keep this story from the press at the time; it would have been the celebrity marriage of the year had he been able to go through with it. But he still had Steph to deal with in what must have been an uncomfortable situation. ‘Steph took it really fantastically well,’ Sheene continued, ‘there’s no two ways about that, and so after a few years it was all forgotten and we agreed to get married when we wanted children. At the end of 1983 we were talking, and I always intended to give up racing at the end of 1985, so I said, “What we should do is, we could get married now, start to try and have children, that’d be really nice.” So we organized to get married on 16 February 1984 and then we started [trying to have children]. Steph had gone off the pill sort of three months beforehand, and we thought, “Right, we’ll start trying for kids now,” and the very first time we did it without protection she fell pregnant and Sidonie was born nine months and three days after we got married.’

After Sheene fell for Stephanie, a new passion for flying helicopters filled the women-chasing void. He might not have been any good at school, but Barry displayed his potential for learning by sitting and passing his helicopter pilot’s licence with ease and in record time – just three weeks. The instructors at the flying school said it couldn’t be done in that timeframe, but Sheene insisted it had to be because that was all the time his hectic schedule would allow. Barry passed his final exam on the very last day of his three-week course in the winter of 1980–81.

Today, many motorcycle racers – Mick Doohan and Jim Moodie, to name just a couple – fly helicopters, but back in 1981 Sheene was, as usual, the first. For anyone used to handling a motorcycle at 180mph, learning the physical aspects of flying helicopters appears to be relatively easy, but what was outstanding about Sheene getting his licence was that he managed to apply himself to studying for and passing all the written examinations. Just as he had demonstrated with languages, Sheene proved once again that it wasn’t a lack of aptitude for learning that had kept him back at school, it was simply because he didn’t want to be there. The late Steve Hislop, eleven times TT winner and twice British Superbike champion cast some light on the scale of Sheene’s achievement. ‘You have to be very committed with your studying if you want to fly a helicopter as you have to sit exams in air law, navigation, meteorology and all sorts of technical stuff like flight performance, planning and human performance. And you also have to type-rate for different kinds of helicopters [like passing another driving test every time you change car]. I know that Barry has flown Enstroms, Jet Rangers, Agustas and Hughes 500s, so he would have needed to type-rate for each one.’ Just months after being interviewed for this book Steve Hislop was tragically killed when the helicopter he was piloting crashed near his home town of Hawick on July 30, 2003.

Sheene had previously owned a Piper Aztec aeroplane, a light, twin-engined six-seater which he often hired out for charter work to earn some extra cash, but he sold it in 1982. Having found light aeroplanes unpractical for flying to race tracks where there is not always enough room to land, Sheene bought himself an Enstrom 280 Turbo three-seater helicopter capable of almost 120mph. He singlehandedly set the trend for turning up at bike meetings from the air, thus avoiding the queues, cutting down on travel time and further enhancing his image while he was at it. There was another practical side to buying a helicopter, as Sheene explained to Thames Video. ‘I spent money on cars, which was a total waste of bloody time. At one time I had a bloody Rolls Royce, a 500 Mercedes, a 928 Porsche. I walked outside one day and thought, “What on earth do I want this for?” So by the next day I’d got rid of two of them and I bought a helicopter. The helicopter was something that enabled me to do five or six things in a day, and it was productive because in a week I’d be doing 30 things that I got paid for so it was something that earned itself a living.’