Читать книгу The Twinkling of an Eye - Sue Brown - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

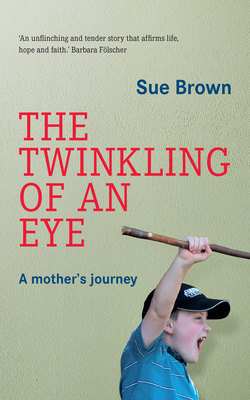

THE GRIN THAT STOLE CHRISTMAS

Оглавление‘I can’t explain myself, I’m afraid, Sir,’ said Alice,

‘because I’m not myself, you see.’

‘I don’t see,’ said the Caterpillar.

‘I’m afraid I can’t put it more clearly,’ Alice replied, very

politely,’ for I can’t understand it myself to begin with;’

– Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

____________________________

I have always loved the beautiful simplicity of that first moment of a family holiday.

Neil, Meg, Craig and I are together in the car, packed with all we need for the next carefree week or two – dog, cats and guinea pigs safely at the kennels; house locked and the busy excess of our lives left behind. I can feel my shoulders relaxing as we drive around Rondebosch Common, past the Red Cross Children’s Hospital on the corner. All that we really need, and all that gives me joy, is contained within the car’s sheltered interior.

The familiar opening lines of Stewart and Riddell’s fabulous Muddle Earth audio book, describing the moon as being as yellow as an ogre’s underpants on wash day, set a light-hearted tone as we join the N2 freeway. And we are on our way.

This December it is a particular relief to be done with the pressures of school and work, and to be leaving town for ten summer days at Arniston, a restful seaside village three hours east of Cape Town.

Recorded by Meg on her camera, Craig is in a silly mood. He entertains us with an imaginary character puppeteered by jauntily perching his sunglasses on his knuckles. He sings us songs, his water bottle a pretend microphone, and points out pastures filled with placid, grazing sheep – ‘Georges and Georginas’, as he calls them.

Soft shadows of clouds laze across the red earth and yellow-green fields of the Overberg, the Western Cape’s blue mountains rimming them all. The road winds seaward. Past the towering grain silos of Caledon, the farmlands flatten out, and the sky seems to expand accordingly. We marvel at vast groups of our national bird – exquisite blue cranes.

The white-washed, thatched cottages of Arniston are in sight when I hear Craig’s gruff voice speaking to my mother on his cellphone: ‘Hello Granny, it’s Craig! I haven’t seen you and Grandad for such a long time. Please will you come to Arniston with us at Easter time?’

I smile across at Neil, a little puzzled at, and amused by, this initiative.

‘It will be so fun and all!’ His final, irresistible addition to his invitation. I am surprised when my parents, having said that they find the long trip from Hilton village in KwaZulu-Natal down to the Cape too much, immediately say yes to their grandson.

He is not surprised at all.

Holiday smells of salty air, roof thatch and freshly laundered linen welcome us into the cottage that we have rented for the past two Easters. Craig makes a beeline for the cosy upstairs lounge that he commandeers as his room, craftily escaping from helping to unpack the car, and finding instead the overflowing bookshelf of his favourite Calvin and Hobbes and Madam and Eve cartoon books. The physiotherapist in me insists that he is now too tall to curl himself into the little alcove bed, so he will sleep on the daybed instead.

My sister Kate and husband Alex arrive to join us. We are soon down on the beach flying kites and playing beach bats with Meg and Craig. My bachelor cousin David also drives out from Cape Town. His theatrical bent and fun-loving nature are enthusiastically welcomed. I photograph Craig boogie-boarding in the chilly turquoise water, yellow sun top clinging to his plump torso. He has gained weight over the past year, asking frequently for snacks – but, when I query why he is eating so much, he simply says: ‘I don’t know why, I am just hungry.’

At low tide Neil, the children and my energetic family scale the rugged hill beyond the beach, then scramble down the steep rocks to enter the vast Waenhuiskrans cave below. They return home – where I have sneaked in a quiet afternoon read and nap – after visiting the soft-serve ice-cream van in the beach parking lot. Neil lights the fire for the evening braai. After eating our fill, we clear the table for a relaxing evening of board games.

Craig, usually thriving on the company, seems to lose concentration and interest in the games. He passes the odd inappropriate, harsh comment, which upsets even my indulgent sister. He is emotional and exasperated when I take him upstairs to his ‘man cave’, as we have called his room, to reprimand him.

In the morning he seems lethargic, struggling to keep up with Neil and Meg on the bike ride – unfit and overweight, we decide. Meanwhile, Craig’s daily dose of little white tablets have masked any nausea and jettisoned my suspicion of illness. I listen to the housekeeper’s stories: she is distraught that her teenage son, influenced by a cousin who has been released from prison, has fallen victim to drug addiction.

My son’s behavioural issues pale in comparison.

We enjoy calamari and chips, seafood curries and spicy fishcakes on the Arniston Hotel veranda, and the impossibly beautiful view of the sea and brightly coloured fishing boats. Neil and Craig walk down later in the afternoon to watch Manchester United playing soccer on the hotel’s TV – a beer and Coke respectively in hand.

As on each visit, we drive to Cape Agulhas to climb the red-and-white-striped lighthouse tower, and walk along the path to the southernmost tip of Africa. Craig poses for a photo with one foot on each of the Indian and Atlantic Ocean signs. Meg sits quietly on the rocks and gazes out to sea, brown plait down her back, a wayfarer into her own world.

It is a bleak, rugged coastline, scattered with shipwrecks and their tragic tallies of lives lost. Stark reminders of the power of the sea, and our relative human frailty. A tarnished memorial plaque lists the names and ages of four young brothers drowned together in the wreck of the Arniston. The others walk on ahead, but I linger behind to read, shivering – despite the sunny afternoon – at the words: ‘Erected by their disconsolate parents.’ It brings to mind the story I recently read about Horatio Spafford’s beautiful hymn, It Is Well with My Soul.

Staggeringly penned, I learnt, when Spafford was shown the site in the Atlantic Ocean where all four of his daughters were drowned. Another almost mythical tale of near inconceivable sadness from the 1800s – and of a faith that as a parent I dare not try to imagine.

We return to Cape Town two days before Christmas. I am always reluctant to drive back to the busy city; and this holiday, although a respite, has not relieved my feeling of unease.

Craig had stood next to me at David’s car door to say goodbye, and then horrified us both by jokingly wishing his beloved second cousin a car accident on the way home. I feel sick at this comment, and Craig’s seeming lack of remorse about it. This year, the spirit of Christmas feels somewhat absent.

Falling ill and on antibiotics, I stay at home on Christmas Eve. Neil takes an excited Meg and Craig – wearing his black fedora, as he does for all special occasions – to David’s for dinner. But our party-adoring son excuses himself from the table, only to be found fast asleep on the couch.

But the next morning is Christmas morning, and concerns are obscured by the thrill of opening presents, and the big family lunch at Neil’s parents. Craig is delighted with his new tennis racquet, and the irregular bounce of tennis balls lobbing against the wall outside is comfortingly normal as the day draws to a close.

On Boxing Day Craig appears in the lounge doorway in his pyjamas. He looks straight at me and smiles; but it seems that only his right eye creases, and that it is only his round, right cheek and corner of his mouth that lift. Assuming that he is doing this to imitate his teen idol, I probe him about the marked asymmetry of his face, my tone almost an accusation: ‘Does Justin Bieber have a lopsided smile?’

He looks a little puzzled, then tries again, managing a somewhat-more-even smile.

Steeped in denial, this amazingly soothes me for a little longer.

Halfway through an afternoon play session with Dylan, the two of them appear dripping wet in the kitchen. Craig is ashen. Claims he has developed a sudden, severe headache while swimming. He vomits, then insists he is better. He is sick again while we drive Dylan home, but cheers up for TV on the couch – even surprising me by asking for supper.

On 30 December our son begs to go to bed while we are entertaining friends – to which I irritably respond that he must not be rude.

It is only on the very last day of 2010 that this curve of escalating symptoms would reach its critical mass – at long last assuming its true form, breaching my maternal defences once and for all.