Читать книгу The Twinkling of an Eye - Sue Brown - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

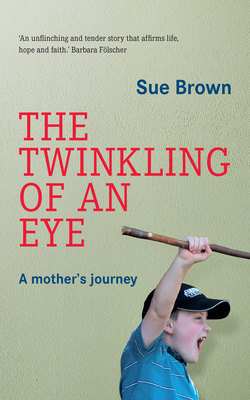

FAMOUS CRAIG BROWN TAKES CENTRE STAGE

ОглавлениеI’m not sure what I’ll do, but – well, I want to go places and see people. I want my mind to grow. I want to live where things happen on a big scale.

– The Ice Palace by F. Scott Fitzgerald

____________________________

‘I don’t want a shaved head!’ says a worried Craig to his doctor. It is the morning of Sunday 2 January. Dr Farrier has examined Craig – and he is happy for him to go home until the operation. My child has had two days to adjust to the idea of this tumour that is inside his head, and his thoughts are now turning to the practical aspects of getting it out – in particular, what will be done to his hair.

‘If you are prepared to have a number-three haircut, we will not have to shave,’ replies the sympathetic surgeon, himself the father of two young boys. Craig visibly relaxes onto his pillow at this acceptable compromise; and also at the feeling that he has been heard, that his concerns will be respected.

We drive to the hairdresser first thing Monday morning. Now so aware of the raised pressure on his brain, and the possibility of further bleeds from the tumour, the world outside of the hospital’s controlled environment feels a frightening place. I am also reluctant to bump into acquaintances, not ready to tell such sensitive news to just anyone.

Craig is known at the salon for unfailingly putting on a great show of protest at each back-to-school haircut, and for his very genuine attempts to talk his way out of their thorough washes.

I briefly explain the reason for this unexpected visit. The staff’s welcoming smiles fade.

I sit in the chair beside him – there are no other clients at this early hour – as a plastic cape is gently fastened around his neck, and the clippers adjusted to their number-three setting.

The hairdresser runs it back to front, with utmost care, and the clumps of dark-blond holiday hair tumble one by one, until his head is evenly covered in stubble.

Craig studies himself bashfully in the mirror, and pats it gingerly.

I want to cry at how much younger he looks, so painfully exposed and vulnerable, but I smile instead, and say: ‘You look cool.’ He grimaces at me.

Back at home, Craig resumes his Guitar Hero Nintendo Wii game, having especially asked Dr Farrier’s permission yesterday. As much as watching it makes me nervous, he is also allowed to play his beloved table tennis, but pauses to scratch his arms, itching due to the high doses of cortisone.

Dr Farrier phones in the early afternoon to say that he has found a colleague willing to assist him. Surgery has been scheduled in two days’ time – on Wednesday 5 January.

Reading between the lines, I gather that – in addition to many being on leave, some neurosurgeons would simply prefer to do a biopsy of the tumour – and await the results before attempting such major surgery. I feel the deepest gratitude towards ours – and his colleague, whom I suspect is interrupting his holiday – for doing their all to give my son the best possible chance of survival.

The doorbell rings, and I see a familiar smile and trademark baseball cap. They belong to Dave, my children’s beloved tennis coach. It’s only when he steps inside and removes his cap that I notice he has had a number-one haircut – in solidarity with Craig.

I swallow a big lump, overwhelmed by the generosity of this gesture, and show him through to the TV room where my son is on the couch, worrying about his operation again.

The day before the operation dawns. The TV room already sports an impressive array of gifts and get-well-soon cards from visitors.

The pressure on his brain is still eliciting some inappropriate comments from Craig, whose entrepreneurial spirit suggests that I find him a little bowl for cash donations to capitalise on all this sympathy. On the guilt of those who have been angry with him. I am not quite sure if he is serious or just teasing me.

That night, after he has had his last pre-operation food and drink, he lies in bed and begins to ask all the questions that have been bothering him. About injections, and drips, and I assure him they will put him to sleep using a gas mask before they do anything at all. Where will everything be inserted? And how? How long will it take?

I am surprised I know so few of the answers. Perhaps I have been afraid to visualise the details; perhaps I’ve just decided to trust our surgeon implicitly. But I take a pen and pad from his shelf, and we write down all his questions.

As a game of hope, we also estimate the number of people who have offered prayers, putting that number at about 800. But I recognise a slightly hollow ring to my assertions about the power of all this prayer, as terrified and as tense as I find myself on this night before his surgery.

I sleep on and off – alert for any sounds that Craig has forgotten he is nil per mouth, perhaps to get up for some water, but he seems to sleep soundly. Lying still, I will myself to go back to sleep – to the respite that it offers from the anxious waiting. My retreat to a subconscious place, which I have discovered has not yet been infiltrated by the reality of Craig’s tumour.

Meg sleeps over with her cousins. She has also been spending time with her Nana, and will spend this operation day with a friend, whose mom I know will provide a calm presence. I feel that she will be better off with these other caring people in her life than a mother in fight-or-flight mode.

I have not yet learnt to stop repeating the mistakes I made when I was in and out of hospital before her brother’s birth. That she needs to be involved. That not voicing her worries – in stark contrast to her very vocal brother – should not make me complacent about the agonies she is enduring behind that sweetly smiling face. My maturity, I am aware on some deep level, again lags behind the needs of my eldest child.

We’re up at first light, taking Craig back to ‘his’ room and a hero’s welcome at the children’s ward. His tog bag is packed with clothes, movie DVDs, his favourite Soccer World Cup blanket. His soft dog is safely stowed away for his return from ICU.

Dr Farrier arrives – greeting his patient first, and complimenting him on the haircut, as if he is the only one in the room. The doctor is very quiet. Is this his normal, or is he tense about the surgery he is about to perform?

‘Please can I have the tumour in a bottle?’ asks Craig. ‘I want to smash it with a hammer!’

The doctor smiles. ‘I will have to take it out in very small pieces – but I promise to break it up really well for you.’

‘Has anyone seen the anaesthetist?’ he asks, but finds only blank looks for answers, and little shakes of heads among the nursing staff. But the porters have arrived to wheel Craig up to theatre. It is time to go.

Walking behind Craig’s bed, I see a scruffy man in late middle age walking towards us down the hospital corridor. Papers spill from an overstuffed brown leather bag slung over his shoulder. I feel disbelief that this could possibly be the man about to anaesthetise my son.

Neil stops to help pick up the reams of patient stickers trailing him, on which ‘Mstr Craig John Brown’ are very clearly printed.

‘Sorry I am late, I had forgotten my wallet, and had to go back home,’ he casually explains.

I am overawed at the size of the operating theatre that we enter, its enormous lights like the compound eyes of gigantic insects looming over us. But the efficiency of the staff in their green scrubs – including even the eccentric anaesthetist now at the head of the operating table – calms.

In a cruel parody of the bright lights of Seussical the Musical, not so very long ago, Craig is now at the centre stage of a very different type of theatre. The baby kangaroo has been disrobed of his golden outfit, stage makeup and cocky attitude.

In their stead are a small white body clad only in underpants and a sterile, oversized green gown, and a scalp exposed by a severe haircut.

Shivering, he wiggles obediently sideways onto the narrow steel operating table, and is covered with more of the thick, green sheeting. He asks for a ‘last touch’ of the silver crucifix a friend has given him. I have promised to wear this on his behalf. I hold the hand nearest me under the covers, while he helps the anaesthetist hold the mask over his face with the other.

His eyes close within seconds.

I may now give him a kiss, but I shakily decline: ‘He has not liked being kissed by me since he was three – he would not like that.’

I am gently escorted out of the theatre, stumbling away down the long passages in my own, bulky theatre garb, and slippery, green overshoes. Tears course down my face at the agony of leaving behind my boy, on the other side of those closed steel doors.