Читать книгу The Twinkling of an Eye - Sue Brown - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

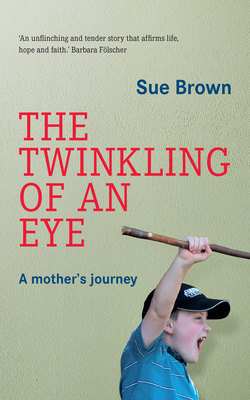

THE BOISTEROUS BOY IN THE CRYSTAL BALL

ОглавлениеBut Reepicheep here has an even higher hope. Everyone’s eyes turned to the Mouse. ‘As high as my spirit,’ it said. ‘Though perhaps as small as my stature.’

– The Voyage of the Dawn Treader by C.S. Lewis

____________________________

‘How are babies born, Mom?’ Craig’s gruff little question hovered, expectantly, inside the warm car. Safely strapped in, the 120-km coastal drive to Hermanus for lunch with friends had kept him still long enough to send his five-year-old mind into overdrive.

Neil, busy driving, had an amused little smile as I swivelled in my front seat to face Craig, launching into my best, impromptu account of his own birth. It was an induced labour in hospital, for which his father only just managed to call a nurse and doctor in time for Craig’s headlong delivery.

I sensed shy Meg squirm in anticipation of her little brother’s verdict, while he paused to absorb the facts. The spreading grin on his round face pre-empted the words: ‘That’s so cool, Mom! So it was just like, “Bombs Away!” ’

As we laughed, I remembered again the awe and gratitude with which I was overwhelmed that day of Craig’s arrival, as I had been on the day of his sister’s birth – so aware that the physical description of childbirth, although enough for my tiny son’s question, fell hopelessly short of conveying the first sight of my babies.

The sense of fleetingly experiencing the mystical, the divine, for there are no words.

I had been dedicated to my work as a physiotherapist for the decade before Meg’s birth, giving my all to my patients’ treatment.

By the time Craig, our second child, was born, I had transformed from one who never cooed over a pram, even worried that I might not feel the same about my own babies, to a woman immersed in full-time motherhood.

There had been concerns about Craig’s growth in utero.

‘Hmmm, growth retardation,’ the radiographer had muttered while doing our 32-week ultrasound scan – after which I religiously rested on my sides to maximise the blood flow through the placenta, until I could feel Craig’s strong movements inside me.

These were worrying days that only heightened our giddy relief at his safe, albeit hasty, delivery, and perfect health.

But his unsettled first night in the nursery led the sage nursing sister to predict: ‘You’re going to have a tough time with this child.’ Lulled into complacency by an idyllic first two years with peaches-and-cream Meg, I smugly dismissed her prophecy.

How difficult could this new baby possibly be? This nurse clearly had no idea what a calm and competent mother I was.

Neil had a demanding job, and had started studying towards a correspondence MBA degree.

He also had, very soon, a newly humbled wife – exhausted as weeks of colic turned into sleepless months. The illusion of the calm, coping mother of his children welcoming him home for dinner was reduced to the reality of a desperate, weepy and barely civil woman. His freedom to play the golf he loved was a distant memory – the closest he came to a course that year was the TV screen, while rocking his unhappy son.

Then one day, a week before his first birthday, Craig decided it was time to walk – showing off to Neil that evening his staggering steps, and his four baby teeth in a huge grin. He sufficiently tired to fall into his first full night of sleep, which meant that we could finally do the same, and life looked up for us all.

‘Oh dear,’ said Meg one day, of Craig’s menacing approach upon her teddies’ tea party, ‘I got a trouble!’ – typically summing up the determination with which he launched himself into toddlerhood. His pale-blue-turning-brown-blanky – its satin-ribbon edge unravelling from the rub of his little fingers – his beloved Barney and ever-present dummy became our critical rescue-and-recovery kit when his plans were thwarted.

I was mortified by my powerlessness to deal with his tantrums in public places, while Meg developed a beautiful way of disarming her tempestuous little brother when the frustrations of life got the better of him.

To Craig’s furious, ‘Meggy, I am going to cut you up and put you in a pie!’ she replied kindly: ‘Oh Craigy, you’ve just been reading too much Beatrix Potter!’

At the other end of his emotional spectrum was a disarming smile, mischievous twinkle in his eye and a no-holds-barred zest for friends and life. He ran to me at the preschool fete to press his gift of a lavender bag, purchased with ten precious tokens, hastily into my hand – leaving me aching as I stood in the sun and watched the back of his little blond head rushing off towards his friends.

I searched through a glut of annoyingly naïve books for help in parenting one so small – yet so astoundingly persistent. My son’s grey-green eyes sparkled with a self-belief, and a competitive streak incontestably his dad’s, but there remained the enigma that was uniquely this boy.

For what purpose had such life force been packed into this tiny child, who was diagnosed with hereditary growth delay at age seven? This little cuckoo chick, or so he felt, in my nest? Small or not, he would warn his friends that they had to be nice to him, because he might be bigger than them all one day.

He had great plans. He would lead a band, be the next Cristiano Ronaldo. Or he was going to make it ‘straight to the big time’ as a top lawyer. ‘I don’t want to work my way up … I already win all the arguments at home.’

Craig’s welcoming beam greeted any guests to our home, impatiently in wait with a barrage of stories to be told. Celebrations were counted down to, and relished.

On sunny afternoons, a friend to play, the air filled with laughter, the scent of over-ripe lemons whacked for a six with a cricket bat, and grass stains on boy’s knees. Calls of, ‘Come and watch, Mom!’ and, ‘We are hungry – but only for treats!’

Craig’s face read like an open barometer of emotions, leaving us in no doubt about his opinions. That charismatic beam would reflect in faces around him – but a cocked right eyebrow could develop into full-blown storm clouds of disapproval, sending all scurrying for cover. Strong feelings that once led to tantrums would mature into an impressive ability to speak up in defence of his friends.

At age ten, a black-and-white sense of justice led him to abstain when asked by a teacher to vote on a classmate’s punishment, insisting on explaining his reasoning in private after the lesson to the surprised ‘sir’.

Craig decided to play chess, ‘which grows brain cells’, rather than much-vaunted rugby, ‘which will damage them’ – an unwitting stand against the fate awaiting him before the end of his junior-school years.

Fondly dubbed ‘The Famous Craig Brown’ by a friend’s grandpa, our son would soon be catapulted ‘straight to the big time’ in a way not even he could have imagined. And I would grasp the awful, and awesome, purpose for which every bit of his irrepressible spirit and feistiness had been intended.