Читать книгу Art of War - Sun-tzu - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

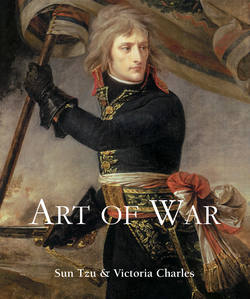

Antiquity to Christianisation of the Roman Empire

Battle of Issus

(5 November, 333 BCE)

ОглавлениеIf your opponent is of choleric temper, seek to irritate him. Pretend to be weak, that he may grow arrogant.

(Sun Tzu, Ch. 1, 22)

In 333 BCE, Darius, King of Persia, at the head of an immense army, marched toward the Euphrates, full of confidence that he could crush the invader, Alexander, as he would an obnoxious insect. With his immense army, Darius continued his march across the plains of Assyria. In the meantime, Alexander had heard that Darius was encamped at Sochos, in Assyria, two days’ journey from Cilicia. He immediately held a council of war and all his generals and officers intreated him to lead them against the enemy. Alexander arrived at Issus, left his sick in that city, and marching his whole army through the pass, encamped near Myriandros, a Syrian city. Darius, having sent his treasure to Damascus, a city of Syria, marched in a westerly direction a short distance into Cilicia, then turned toward Issus. He arrived not knowing that Alexander was behind him, for he had been assured that this prince had fled before him. On learning that Alexander had passed into Syria, he barbarously put to death all the sick that were in the city, except a few soldiers, whom he dismissed, after making them view every part of his camp, in order that they might inform Alexander of the prodigious multitude of his forces. The latter could scarcely believe the report of the magnitude of the king’s army. He immediately made preparations to march to meet the Persians. At daybreak, the following morning, the army arrived at the place where Alexander had determined to engage the enemy.

Having heard that Alexander was marching toward him in battle array, Darius advanced with his army to meet him. Darius made his cavalry cross the river again, and dispatched the greater part of them toward the sea, against Parmenio, because they could fight on that spot with greater advantage. Alexander, observing the enemy’s movements, began immediately to transform his battle organisation, behind his battalions in order to prevent their being seen by the enemy.

Alexander performed the duty both of a commander and a private soldier, wishing nothing so ardently as the glory of killing with his own hand, Darius, who, was seated on a high chariot. Many of the Persian nobility were killed. The horses that drew Darius’s chariot, being quite covered with wounds, began to prance about, and shook the yoke so violently that they were on the point of overturning the king, who, afraid of falling alive into the hands of the enemy, leaped down, and mounted another chariot. The rest of the Persians observing this, fled as fast as possible, and throwing down their arms made the best of their way. Alexander had received a slight wound in the thigh; but happily it was not attended with ill consequences.

The Macedonians also signalised themselves with the utmost bravery, in order to preserve the advantage which Alexander had just before gained, and support the honour of their phalanx, which had always been considered invincible. The Macedonians lost 121 of their best officers, among whom was Ptolemy, the son of Seleucus, who had all behaved with the utmost gallantry.

The routing of the Persian cavalry completed the defeat of the army. The Persians lost in this battle 100,000 men, while the historian relates that Alexander lost only 150 horses and 300 infantry. But the Macedonian loss must have been much greater.

(adapted from: The Battle Roll by E. Perce)