Читать книгу Art of War - Sun-tzu - Страница 25

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

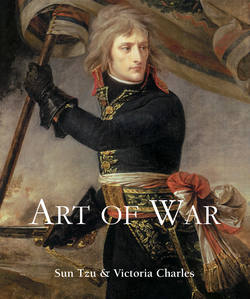

Antiquity to Christianisation of the Roman Empire

Battle of Milvian Bridge

(28 October, 312 CE)

ОглавлениеMilitary tactics are like unto water; for water in its natural course runs away from high places and hastens downwards. So in war, the way is to avoid what is strong and to strike at what is weak. Water shapes its course according to the nature of the ground over which it flows; the soldier works out his victory in relation to the foe whom he is facing. Therefore, just as water retains no constant shape, so in warfare there are no constant conditions.

(Sun Tzu, Ch. 6, 29–32)

The celerity of Constantine’s march has been compared to the rapid conquest of Italy by the first of the Cesars; nor is the flattering parallel repugnant to the truth of history, since no more than fifty-eight days elapsed between the surrender of Verona and the final decision of the war. Constantine had always apprehended that the tyrant would consult the dictates of fear, and perhaps of prudence; and that, instead of risking his last hopes in general engagement, he would shut himself up within the walls of Rome. His ample magazines secured him against the danger of famine; and as the situation of Constantine admitted not of delay, he might have been reduced to the sad necessity of destroying with fire and sword the imperial city, the noblest reward of his victory, and the deliverance of which had been the motive, or rather indeed the pretence, of the civil war. It was with equal surprise and pleasure, that on his arrival at a place called Saxa Rubra, about nine miles from Rome he discovered the army of Maxentius prepared to give him battle. Their long front filled a very spacious plain, and their deep array reached to the banks of the Tiber, which covered their rear, and forbade their retreat. We are informed, and we may believe, that Constantine disposed his troops with consummate skills, and that he chose for himself the post of honour and danger. Distinguished by the splendour of his arms, he charged in person the cavalry of his rival; and his irresistible attack determined the fortune of the day.

The cavalry of Maxentius was principally composed either of unwieldy cuirassiers, or of light Moors and Numidians. They yielded to the vigour of the other. The defeat of the two wings left the infantry without any protection on its flanks, and the undisciplined Italians fled without reluctance from the standard of a tyrant whom they always had hated, and whom they no longer feared. The praetorians, conscious that their offences were beyond the reach of mercy, were animated by revenge and despair. Notwithstanding their repeated efforts, those brave veterans were unable to recover the victory; they obtained however, an honourable death; and it was observed, that their bodies covered the same ground which had been occupied by their ranks. The confusion then became general, and the dismayed troops of Maxentius, pursued by an implacable enemy, rushed by the thousands into the deep and rapid stream of the Tiber. The emperor himself attempted to escape back into the city over the Milvian Bridge, but the crowds which pressed through that narrow passage, forced him into the river, where he was immediately drowned by the weight of his armour. His body, which had sunk very deep into the mud, was found with some difficulty the next day.

(adapted from: The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by E. Gibbon)