Читать книгу The Constant Listener - Susan Herron Sibbet - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

“In the Cage”

August 1907

The action of the drama is simply the girl’s “subjective” adventure—that of her quite definitely winged intelligence; just as the catastrophe, just as the solution, depends on her winged wit.

—Henry James

Preface to “In the Cage” The New York Edition, volume 11

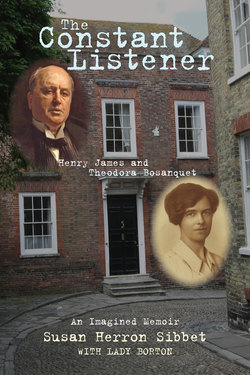

It was no accident that Henry James and I met in the summer of 1907, though I had known nothing of him beyond the revelation of his novels and tales. That heavy morning in August 1907, as I sat in a top-floor office near Whitehall, compiling a very full index to the “Report of the Royal Commission on Coast Erosion,” my ears were struck by the astonishing sound of passages from “The Ambassadors” being dictated to a young typist. Neglecting my Blue-book, I turned around to watch the typewriting-machine operator ticking off those splendid sentences, which seemed to be at least as much of a surprise to her as they were to me.

When my bewilderment had broken into a question, I learnt that the novelist, Henry James, was on the point of returning from Italy, that he had asked to be provided with an amanuensis to typewrite his dictations, and that the lady at the typewriter was making acquaintance with his style. Without any hopeful design of supplanting her, I lodged an immediate petition that I might be allowed the next opportunity of filling the post, supposing she should ever abandon it. I was told, to my amazement, that I need not wait. The established candidate was not enthusiastic about the prospect before her and was even genuinely relieved to look in another direction. If I set about practising on a Remington typewriting machine at once, I could be interviewed by Henry James himself as soon as he arrived in London. Within an hour, I had begun work on the machine.

Of course, that morning, when I first heard of the possibility of working for Mr. James and went after the job with all my heart, I’d had little experience of working for anyone. I had graduated from university the year before, with my degree in geology but without any clue as to how I was to make my living. I was only very sure that I did not want to become a teacher as my friends Nora and Clara from Cheltenham Ladies College had reluctantly trained to be. No, I had already tried the local dame school while waiting to pass my university entrance exams, and I knew I could never do that again. Like Nora and Clara (and unlike most of my other classmates at Cheltenham), I knew that I would not be marrying any time soon, if at all. Instead, when we finished our training, Nora, Clara, and I went to London and shared a flat. While Nora became the administrator of a small girls’ school, Clara and I looked for other possibilities.

It was Clara who found Miss Petherbridge and her establishment to train educated females for practical jobs in the Whitehall government offices that were now at last opening up to young women seeking employment. Miss P. was a middle-aged spinster, ambitious and kind, who happily kept us practising away in rooms she had found near Whitehall. No matter what level of education we had upon arrival, Miss P. started us all at work on the very lowliest of government tasks, and so I was there training to be an indexer—not a stenographic typist or any sort of typist.

Saying that I knew nothing of Mr. James beyond the revelation of his novels and tales actually means that I knew quite a bit about him. Mr. James had been part of my life ever since I was able to read his work by myself. His characters were my friends, his heroines aspired to the same high goals I did and had the same wishes and dreams that I did. I eagerly devoured each new book as it came out, delivered to us by Mudie’s Lending Library.

I remember the lost afternoons when I first found “The Portrait of a Lady” and devoured it, lying in my bedroom, weeping silently, feeling the great promise of that brave girl and how the cruel and more experienced, unscrupulous friends surrounded her with their selfish schemes and blinded her to what might bring her happiness. I loved all Mr. James’ poor, blighted young girls—Daisy and Nanda and Maisie and Fleda Vetch, even poor little wild Flora in “The Turn of the Screw.” I believed Mr. James gave me, with his stories of the pain and power of cruelty and of love, of open deceit and agreeable divorce, of new and old wealth, a more realistic idea of what went on in the drawing-rooms of Belgravia and maybe in the girls’ bedrooms at Cheltenham than had any sermons in my father’s church.

And so, after I went to Miss Petherbridge to ask for the chance to work with her esteemed client, Mr. James, she agreed that if I would practise and be patient, soon enough she would arrange for the promised interview with the famous author.

Our offices near Whitehall were too noisy and public for meeting prospective clients. Because Miss P. and Mr. James were old acquaintances, she arranged for our appointment to be at her flat late one afternoon on a long, hot August day. I walked the few blocks in the hopes that stretching my legs would calm me. The hot sun glared off the hard, white house fronts; as I climbed the steps, I could feel my shirtwaist sticking to my back, where the heat had made it quite damp. I banged the knocker and was shown into a sort of anteroom to wait. Miss Petherbridge and Mr. James were talking; I could hear their low voices from beyond the closed door, and then the door opened.

Miss Petherbridge came out, all cool and comfortable in a crisp, beige linen dress, which I had never seen her wear at the office. She apparently had dressed up for this meeting. She had done her hair differently, too, not all pulled back into a bun but with side curls, softer, more attractive. Since she was tall, taller even than I am (and I am nearly six feet tall myself), it seemed strange for her to look so delicate. I put my hand up to my hair and its combs and pins, afraid to think how I must look after my hot walk.

Miss Petherbridge seemed more excited than usual. Her voice was high, and the words came fast.

“No, no, my dear, you look fine, come in, don’t keep Mr. James waiting for you.” She held the door for me to go into the front parlour. Her introductions were quick. Then she was gone, and I was alone with Mr. James.

I stood speechless in panic, but to my relief, I found I would have time to retrieve my composure, time even to study this great man, for he immediately began to speak at length, and apparently he expected no response, since he left no pauses.

He was standing beside the fireless grate and gestured for me to join him and sit down. As we settled ourselves into the two chairs set facing each other, I noticed that he was dressed in a rather peculiar combination of the properly dark morning coat and trousers worn with a most un-British sort of soft and flowing silk tie in a brilliant red and blue spot, and with a broad, expansive waistcoat of a comforting yellow check. It made me wonder who chose his clothes. I knew he had never married, but it did make me feel a bit more relaxed to see his not-infallible taste displayed. Perhaps even Mr. James was a victim of his own enthusiasms; perhaps after all his years in England, he had still not quite got the hang of our English taste. Perhaps there was something I could do to help him.

As he continued to express his apparently deep and long thoughts about his pleasure in making my acquaintance, I looked into his open face and was quite struck by his handsome, bright look. His eyes were clear, grey, penetrating and now were slightly twinkling at my own apparently staring, curious gaze. He was tan, quite burnt actually, and his light hair was only a fringe about his beautifully shaped, shining head.

I wondered where he could have been travelling, to be so tan, and as if reading my mind, he went on, saying, “I’m just back from a month’s motor-flight with my dear friend, Mrs. Wharton, in her amazing automobile, speeding along that glorious hilly spine of Italy. With her usual good fortune, even on the voyage home we enjoyed the best weather.”

I thought then that he had the look of an experienced sea captain, with his brown skin and those direct, sharp eyes, but I wondered at the mouth, such a sensitive, expressive feature. No, no sea captain would have survived with so much of his soul revealed as Mr. James. He was still talking in his beautifully resonant voice, with neither a British nor an American accent, I noticed.

“Miss Bosanquet, I want to be sure you understand the special circumstances, the arrangements I require for someone to come to work for me. My home is in the most provincial and adorable of towns, the ancient village of Rye, on the Sussex coast, a perfect antique town, but very quiet, nothing there for a young woman to entertain herself. Well, there is golfing, I suppose, but then you perhaps don’t aspire to that most daunting of sports.”

I was so amazed at his gentle, kind manner, his apologetic tone that I could barely pay attention to what he was saying. Was this the great novelist, the author of the terrifying “The Turn of the Screw,” the shockingly risqué “The Sacred Fount,” the deeply disturbing “The Golden Bowl”? Here was that looming presence, the mind that had put forth such monumental works, novels of such depths and heights—cathedrals, even. Now, was he asking if I desired to play golf? I could hardly believe my ears.

Mr. James went on. “The work itself will not be too taxing, I trust. We will work every day, including Sundays, for three or four hours, from ten to one. There may be other typewriting projects for you after our mornings together, making clean copies, corrections, but those morning hours of ours will be sacrosanct. Perhaps Miss Petherbridge has told you of my current project, that I have embarked on a massive effort, the revised edition of all my most important works. I will include only the pieces I deem worthy, and there will be corrections and revisions to be made, but most of our time will be used to dictate the prefaces for each volume as I come to them. At present I have the first seven prefaces completed, but now I need to pick up the pace.

“As you will find out, I like to write while standing up, moving about, dictating to a steady typewriting machine; I like the ease of speaking these essays of memory, these excursions into my thoughts about writing itself. I got into the habit of dictating about ten years ago, when I had something wrong with my right hand and arm. It happened part way through a short novella—‘The Awkward Age,’ I believe—and the new procedure seemed an aid to my imagination. I liked it, though there are those who don’t agree. My brother says he can tell exactly where my dictating began.”

I could only nod my understanding, my appreciation of his problems then, his huge project now, but some small voice was niggling away in me, asking: What was I letting myself in for? How many years would I spend doing someone else’s work when all I really wanted was to work on my own writing? Ever since my dearest friend, Ethel, had encouraged me to use my brain, to follow my aspirations, I had dreamed of writing. I did not know what, exactly, but I knew that I would have to earn my own way, and it would be a struggle. But now, should all my time and energy be given to someone else’s writing, even to someone as famous as Mr. James? Yet I wanted to be there, I wanted to learn, to be inspired in his presence. I wanted to be generous, and so I pushed those thoughts away, and with my whole being, I kept nodding, agreeing, ignoring that little, selfish voice.

Mr. James described the arrangements he had undertaken for the comfort of his amanuensis: There was a boarding house called Marigold Cottage quite nearby, with an accommodating landlady, Mrs. Holland, whom he understood to be a good cook and who would provide me with a room and meals. We would work at Lamb House. He had arranged for delivery of a fine, new typewriting machine, a Remington, the best, he had been told, all in order to make my work even easier. He went on in his quite charming way, in spite of my shy, frozen silence in response.

Soon enough I was back outside on the dusty, bright London street, having agreed to everything, even the very low rate of pay he was offering. I knew nothing of payment—I had never yet been paid for any of the work I had done on the indexing, since I was still in training. In fact, I had no idea of whether Mr. James’ arrangements were good or even proper. Should a single young woman go to a man’s rooms, even such an older man, to take dictation to his typewriter (as we stenographers were called in those days)? It was all a new business to me, for I had only worked for a few months with Miss Petherbridge and her “girls,” as she called us.

In 1907, Miss Petherbridge found us girls, or sometimes we found her. We were that new phenomenon: university-educated young women, women who wanted more from life than to wait at home and pull taffy until we married. We were what the newspapers called the “New Woman.” No one quite knew what to make of us.

The infernal typewriting machine was changing everything. At first, the machines were a mere substitute for the local printer down the street or the copyist who worked late nights to ensure that a court brief or financial agreement had the correct number of copies. But as more typewriting machines appeared, the arrangements of work-rooms and offices had to shift, because the stenographers became women willing to work for lower rates than male secretaries and copyists.

Previously, most novelists, including Mr. James, had written quickly in longhand, with the first version the final version. They were accustomed to sending their pages straight to the publisher to have the lines typeset; perhaps even Mr. James was never truly sure what he had written until the galleys came back as proofs to be corrected. Now, with the typewriting machine, all that had changed. Thoughts of personality, handwriting, and female circumstances meant nothing when a man could dictate to the typewriter. We would take down all the man’s words and arrange them into one clean copy ready for his immediate corrections and our retyping.

This was the new method Mr. James was in love with, the machinery he wanted me to be his agent for, yet when he interviewed me, I still had not learnt more than the rudiments of that process or how to use a typewriting machine.

I went to Miss Petherbridge the next morning to report on my interview and to hear from her what the financial arrangements to which I had agreed really meant.

“Oh, dear, Miss Bosanquet, you have let him take advantage of you, if I do say so myself. Even if he is my old friend, I am surprised at him. What did you ask?”

“I didn’t ask anything. In fact, I think I hardly spoke a word; he seemed to do enough talking for the both of us.”

“Well, perhaps I should have prepared you. When Mr. James came to me, asking for a special sort of young woman to be his amanuensis, he even admitted that it was because a woman would be less expensive than a man. This enormous project of his—it’s weeks, months, perhaps years of work! Poor Mr. James was concerned how much it would finally cost, and a woman does require far less, after all, than a man who might have a family to provide for. But my dear, I am glad for you! You must have made a good impression to have him make up his mind so quickly. Well done! Congratulations!”

“But Miss P., there is one difficulty—I’ve only the barest idea of how to use the machine. Can you suggest someone to give me lessons or perhaps a book I could use? Can I learn to typewrite quickly enough? He wants me to come to him in a few weeks.”

“I know what you need,” Miss Petherbridge said in her usual brisk way, and soon enough I was seated in a private office at the end of the hall before the large, shiny, black-and-gold apparatus, and a book, “The Curtis Method to Speed Typewriting,” open to “Lesson One: Familiarise Yourself with the Machine.”

I prided myself on being good with machines. At my home near Lyme Regis, it was my responsibility to keep the bicycles in good working order. I kept my own tools, wrenches, grease can, and oil can in the tool shed, and many times I would go out there when I wanted some quiet, away from my father and his little voice practising his sermons or reading out articles of interest from the weekly paper. In the tool shed, I could take my bicycle apart, spread the pieces all over the floor, and work for hours, happily forgetting all about his demands. Because I was famous for my knowledge of bicycles and other machines, even my most proper friend, Ethel Allen, and her sister often asked me to come down to St. Andrew’s to look at their bicycles. Usually it was some mechanical problem, nothing very complicated, often a loose chain or brake pads to be tightened. I always dropped my own tasks and sped down the hill from Uplyme for any chance to be with Ethel.

I suppose in those days, still in the reign of Queen Victoria, it was unusual for a girl to be interested in machines, but I always had been. They made sense to me, somehow—logically constructed, beautifully put together. Unlike with people, if something went wrong with a machine, using attention and patience, I could figure out the problem and make everything right.

This machine I was facing was formidable but not daunting. I soon learnt that I would have more time to practise, for Mr. James could not arrange for my room and board with Mrs. Holland until October.

“The Curtis Method” seemed very clear and logical. Soon enough, as instructed, without looking at the keys, I was practising away, typewriting, but only the silly nonsense words for those first lessons. I opened the book:

bab cab dab fab gab

bob cob dob fob gob

I thought how strange English letters and words could be. Whatever makes us speak as we do? My mind would wander off, my hands would slip to the wrong keys, and I would have to start again:

cat cot cut dot dat dut

This project was becoming less and less appealing. I did want to work for Mr. James, even for his low rate of pay, but why did the typewriting have to be so boring?

However, I did improve as the days of practise went on. Soon, I was ready to try sentences, paragraphs, even whole pages, but I found that going for speed had its disadvantages. Not looking at the keys but, instead, using the home keys was actually quite difficult. One slip and my typewriting turned into

qw294lit rqw5, e3lig34q53ly,

2ihou5 e3lidqdy, 5 h3 435u4n.

What I had typed did not make any sense! My fingers had been on the wrong keys. I moved them and tried again. All was well, until I lifted my hand to throw the carriage return and once again came back to the wrong keys. Perhaps I needed to abandon Mr. Curtis. I did not have time for this. I tried looking down at my fingers for several words—my words!—and it was better. I could still use the home-key method, but if I could look to find the less familiar keys—the O, the P—it was much better. I hoped if Mr. James were simply dictating, I would have a chance to look down, and I might be able to typewrite for him without so many mistakes.

One afternoon, in frustration, I pulled a newspaper from a pile and began using the typewriting machine to copy the first article I saw:

The New Woman

Special to the “Gazette” by M. Perry Mills, on assignment in America, August 1, 1907

It is only at the end of the last century that women have entered the professions or gone into business. Among our grandmothers it was an unheard-of thing for a woman of good family to earn her own living. If her husband died, or if she were a spinster with no money of her own, she was taken care of by the next of kin in the masculine line, or scraped together a scanty living doing embroidery or some other “ladylike” task. It never even occurred to her that she could fit herself out for work, enter public life or the professions. . . . Such a suggestion would have been met with exclamations of horror as something truly impossible and unfeminine.

My thoughts went to my aunt Emily and the box of books our “maiden aunt” always brought along with her when she was required to come and stay with us. How I suspected she might have longed for an education.

Reading on, I skipped down to

How different conditions are today! Girls go to college with their brothers, take their degrees and sally forth into the world to struggle for themselves, if not on quite equal footing with men, yet every day more and more attaining that end. It is the age of “working women.”

And yet such a state of affairs did not come about suddenly, nor is it wholly the result of women’s discontent with domestic life. It is rather more the outgrowth of the times—the natural evolution of womankind in the history of the race. The increased cost of living, the higher standard required of young men entering the professional and business life, and the consequent necessity of prolonging the period devoted to preparation for that life, are heavy factors in the movement.

That nine women out of ten would prefer marriage and the making of a home for themselves to achieving success in any profession is just as much of a truth today as it was a hundred years ago.

I stopped typing and made a rude noise, then looked around to see if anyone were still in the office, but it was so late that the office was empty. I laughed and said out loud to myself, “This is one to show to Nora and Clara back at the flat!” Then I bent my head back to my exercise book. Meaningless letters were easier to deal with than some idiot’s rantings about the New Woman.

After another hour of practise, when the evening light was nearly gone, it was time to stop and go back to the flat or do something fun. I rubbed my hands, stretched my fingers wide apart, curled my fists, and, with a groan, stretched my tired arms over my head. I heard an answer to my groan.

“That bad, is it?”

I turned to find that Clara, my closest friend in London, had come in behind me. She came over to give my shoulders a quick, comforting squeeze. I must have seemed tired. She looked as fresh and bright as when she had set out that morning from our flat for her job as secretarial assistant to Lord Milne. Her perfect frock was without a wrinkle, her heavy gold hair was still perfectly smoothed up into its high combs, her clear white skin was as flawless as ever. I put my hand up to my chin, where I knew there was another inky blotch. Clara laughed her light laugh and held out my jacket from the rack by the door.

“About ready to go? We can stop for a quick bite at the pub and still reach the theatre in time.”

I collected my things into my string bag. “I’m so tired. I’m not at all sure about this . . .” and I showed her the exercise book. “It’s been weeks, and my neck hurts, my fingers are sore, and my back aches. I actually like it when the machine breaks down. I know how to fix the blessed machine—but I don’t know how to use it.”

“Now, now, Dora, you always underestimate yourself. You’re getting really good. Look at this!” Clara pulled a sheet from the waste-paper basket and read in her melodious voice, “Pap nap tap sap, pip nip tip sip, pop mop top sop. Not one mistake! Oh, look at this one!” Clara picked up several half-filled pages lying on the table beside the machine and read out loud,

The Tattler Tells All

The Huntsman’s Ball was honoured with our most brilliant young debutentes, Miss Georgina Sedly and Miss Maria Whitworth, but the person most talked about this lively season is the handsome raven-haired, blue-eyed Miss Margaret Haig Thomas. . . . It is rumoured that Miss Thomas, one of the wealthiest daughters of the land, may soon be leaving our glittering dinners and gorgeous balls for the less than brilliant weather of Oxford and the dingier halls of Somerville.

“Dora, what made you type that one?”

“I don’t know. It caught my eye, someone very rich who leaves the social scene to go to university—It seemed different.”

“This is good typewriting. You’re getting better. The only mistakes here are in the spelling of ‘debutante’ and in the spacing.”

I put the cover over the machine with one motion, then gave the cover an extra tug. “I hate the space bar. I hate the machine. I wish I could secure this job some other way.”

I took Clara’s arm as we walked side by side down the long hall, past the empty rooms. “You know, Clara, there really are not enough jobs. Even if all of us go to university and complete our degrees, there will not be enough work for women unless men open up the rolls and hire women to teach in men’s classes, hire women to write and edit the newspapers and books, fill the publishing houses, hire women to be the lawyers and clerks and agents.”

Clara stopped and turned to look at me. “Dora, you surprise—You, the shyest woman I know, you’re starting to sound like one of those militant Suffragettes.”

“But, Clara, I’m stuck. I have no money of my own, only a little more than the hundred pounds a year my mother left me. And my old home is no longer my own, now that Father and his new bride are all caught up with planting the garden with exotic shrubs. The only future Father and Annie can imagine for me is to teach horrid little girls or find a husband or move about again and again to all the cousins. I guess Annie still believes I will find someone to marry someday. After all, I might have the same good luck she did, catching someone older and settled, like my father.”

“Can you try to talk to them, tell them that what you want is different, that you want to be on your own?”

“Oh, no, no. I feel muffled up and invisible when I’m there. I don’t dare even speak. But what I really want is to write. The real excitement of this typewriting business is that now I can typewrite my own stories and make them look quite professional, as if I had hired a secretary. It’s curious what the typewriting does. I can feel my writing all so much more clearly when I am typing my own words. It flows out of my fingers; it’s so different from writing with a pen. I even practise on the typewriter on pieces from my diaries. Maybe I’ll send them to you and Nora when I am with Mr. James. Oh, I don’t know how to express it, but taking this job seems to be changing everything.”

Clara was a little breathless, trying to keep up with my longer legs as we walked quickly along the street towards the entrance to the Tube. “I’ve always liked what you write, Dora—your letters are wonderful, and your essays and stories. Someday you’ll be published, I know. Only, I wonder, if you do get the job, what will Mr. James think of another writer in his room?”

“I would never tell him. I could never tell him. I imagine he will think I really don’t know very much, that I’m only a girl who happens to be there to be the extension for his hands. I don’t think I would want him to know much about me, about what I do know. That will be my secret.”

“How can you keep yourself secret? You’re so obviously intelligent and capable.”

“But you see, I wonder if he would want anyone for his amanuensis who was too smart, too able. My father used to say that I should hide what I think, that men never like it when a woman seems to know too much. Besides, it will be easy for me to be quiet with Mr. James. I probably will not be able even to speak around him for days.”