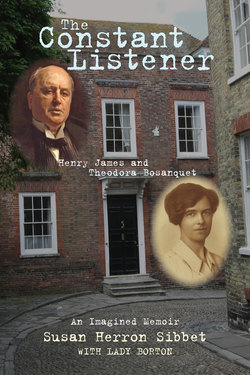

Читать книгу The Constant Listener - Susan Herron Sibbet - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

“The Spoils of Poynton”

1908

The horizon was in fact a band of sea; a small red-roofed town, of great antiquity, perched on its sea-rock, clustered within the picture off to the right; while above one’s head rustled a dense summer shade, that of a trained and arching ash, rising from the middle of the terrace, brushing the parapet with a heavy fringe and covering the place like a vast umbrella. Beneath this umbrella and really under exquisite protection “The Spoils of Poynton” managed more or less symmetrically to grow.

—Henry James

Preface to “The Spoils of Poynton” The New York Edition, volume 10

As it turned out, after the excitement and strain of Aunt Emily’s visit, I was needed to help Mr. James keep on the narrow track, back to the prefaces. As the dark winter days shortened, our work seemed to slow. We were poring over several volumes containing all his short stories, struggling mightily to fit them into a new arrangement. The publisher thought the volumes would be too long with the way Mr. James had so carefully divided them.

Some mornings, I could see that Mr. James was tired, even when we started. From the quantity of new work he had readied for us by hand, apparently the night before, I wondered if he had slept at all. It was on one such morning that he seemed to be having more of a struggle to locate the exact word, and his usual slow pacing before the windows became halting, even agonisingly blocked. Finally, he stood at the mantel, his bent back to me, apparently thoroughly stumped for the word, audibly searching among the many possibilities, ones that sounded the same, ones that had the same rhythm of syllables, ones that meant somewhat the same:

“. . . the air as of a mere disjoined and lass—lassitudinous . . . asinine . . . [long silent pause] . . . acerbated . . . exacerbated . . . exasperated . . . aspiration . . . aspirated . . . [longer silent pause] . . . ulcerated . . .”

Through that struggle, my mind began to wander, since my chosen book that morning had not been good enough for such a long pause. I looked down at my shirtwaist, with its crisp white pleats, and tried to brush away a smudge from the carbon paper.

Mr. James spoke. “Now I’ve got it: disjoined and lacerate-d lump of life . . .” Then he went back to his notes, and we marched endlessly on.

Shortly after one in the afternoon, Mr. James put away his notes. His tone was kindly. “I believe that’s a goodly amount for today, Miss Bosanquet. I wouldn’t want to appropriate your afternoon as well. We’ll begin again tomorrow at this spot.”

I pulled the cover over the typewriting machine and stacked the good copies and carbons.

And then I was free to return to my rooms and try to wash out the smudge, for this was my last clean shirtwaist, and I had no time or money for the laundry.

I had been well trained by Miss Petherbridge to watch every detail of my appearance. I was most particular whenever I went to Mr. James. I had only a small dresser mirror in my dark little room at the back of the house. I could slant the mirror up to fix my hair or slant it down to try to see if my hem was straight or my stockings had gone baggy and wrinkled. I never have wanted for much of a mirror, but I remember that room and that mirror as a particular trial. Getting ready in the morning, I would actually change my shirtwaist several times and turn back and forth before the mirror in that cramped room, trying for the best effect, that desired combination of crisp, tailored efficiency and tender, helpful femininity. In those days, I still had hopes for some possible combining of the two very distinct and combative parts of my nature.

“My nature”—What a strange phrase that is, implying so much of what I was born with, like a wild animal, and yet also with a meaning of what I myself added, what I brought on myself.

“My nature”—I am flooded with all that phrase contains—my family and how they struggled with my wild nature, how my mother tried to make me appear sweeter, smaller than I was, bedecking me in frilly dresses, pulling me close in those old photographs. And my wild behaviour: No one could rein me in, not even when my mother was ill, not even after she had died. I roamed the cliffs and hills of Lyme Regis, met my friends secretly and helped them to write and perform plays.

I was a puzzle to my parents. Only my cousin Queenie really understood. Once when we were all together at our grandfather’s, she told my fortune, using the latest fad, phrenology, to read my character from the bumps on my head. Meanwhile, she helped me do my hair, putting it up for the first time. It was that sad, lost Christmas when my mother was quite ill, and so I had gone to Queenie for help. She was the girl cousin closest to me in age, one year older but much more experienced. She lived in London, and she went to parties all the time.

I can remember the feeling of her brushing and brushing my unruly hair, and then she surprised me by her comments, saying I had an interesting head, and that she could read my character from its shape and its various bumps.

I held very still, and she moved her soft, delicate hands through my hair, gently massaging and talking in her beautiful, low voice.

“Dora, I can feel that you are jealous and a flirt.”

“I don’t believe you.” She was right, but still I had to act sceptical. “How can you tell that?”

“No, wait, I can do more. You are generous, sulky . . . you have no religion but some affection.”

I knew she was even more correct, at least about being sulky, as my poor father could attest, and about having no religion; I thought of all the missed Sundays, the giggling through chapel. I relaxed even more into the wonderful feeling of her hands.

And certainly I was a flirt—ask my friends from Cheltenham Ladies College, that very particular finishing school my parents had, with great hopes, sent me to. Sometimes we would have a dance with ourselves, no men, after a formal dinner in the Great Room at Holyon House, and we would all dress up in our long white gowns, practising with each other the different steps. I loved to dance, and I went from girl to girl, wanting to dance with everyone. During our secret cocoa parties, after the lights were supposed to be out, going to each other’s rooms, I would go to so many different rooms that my friends would tease me about being an outrageous flirt. But I liked being friends with all the girls. I did not mean to flirt; it’s that I have always been curious about other people. I want to understand what they are really like.

I suppose Queenie was right. I did want to be generous and affectionate, but then that jealous part would come in and make everything complicated. I remember wailing to Queenie, “Why do my friends not like each other, too, as I like them? Why do they always want to have me all to themselves?”

Her only answer was to continue her report: “And you are very independent in some things.”

I liked to hear that; I knew I was named after my father’s father, Theodore Whatman Bosanquet, but I used to pretend I was like Empress Theodora of Constantinople, that brilliant strategist famous for her bloodthirsty appetite.

I asked Queenie, “Do you think I’ve had too much freedom? I sometimes behave as if I were a boy, but I’ve been alone so much, I don’t know. I wonder if deep down I’m not all mixed up. Maybe I really don’t care about what people think about me and how I act. I’ve always liked being odd, liked being the one to fix machinery, and to be really good at cricket when girls are not even allowed to run. I like to write my own bloody adventures.”

Queenie went on touching the surface of my head and along the ridges behind my ears, then moving up to the tender area along the temples. “I can feel that you are artistic and not at all practical.”

How could she have thought that? Whenever I tried to draw, it came out looking strangely flat and dead—like my old fossil-rock drawings from the Lyme Cliffs or the sketches of dissections I used to do with my father. I have always wanted to be around people who are artistic, but until recently I was a little afraid of them, too. Where do they find their ideas? They seem so self-sufficient, so centred on themselves.

I wanted Queenie to go on, and I asked her if those two characteristics, being practical and being artistic, had to be opposites. I certainly felt practical, if being practical meant keeping track of the details of daily life, such as knowing how much money was left in our household account when my father left me in charge. To my mind, being practical meant listing the pantry order perfectly before the household ran out of things and before my father shouted at me again for forgetting. But being practical also meant teaching myself to refrain from turning silly and sentimental about my feelings, such as missing my mother, or my pashes at school, or worrying over whether anyone really cared for me.

But by then, Queenie had finished pulling my hair up into an elegant French twist. She shook her head at my questions, and with a hug, she gave me one of her own black velvet bows to cover all the stray wisps that still escaped from the combs no matter how hard we tried. And so, beautifully together, we went down to join the family.

Now, standing before that impossible mirror on Mermaid Street in Rye, how I wished Queenie were nearby or at least that I had one of her clever velvet bows with me. What a struggle it was to put my hair up into a simple twist that day, when I was to dress for my first rather large-scale social occasion in Rye, a literary tea-party given by some woman I had not yet met, a friend of a friend. I certainly did not feel very independent or flirtatious. Instead, I felt nervous.

I wondered if I might see Mr. James there, and as I pulled and smoothed my hair tightly back, I had to laugh at the sudden thought of his broad forehead, his smooth skull—What would Queenie have made of his character? I never could induce her to say whether someone could be artistic and practical at the same time. I certainly was learning about Mr. James and his practical, methodical approach to his writing with each new day, but I was not seeing much of what I would have called his artistic side.

I wondered about his other characteristics. I knew Mr. James did not go to church, because he expected me to work on Sundays. I had seen him being quite affectionate with his little dog, Max, worrying over every whimper and squeak. I suppose the world saw Mr. James as a famous man. His books had made him wealthy and independent, but of course he’d had no contrary expectations to fight off, as I had with my family. He seemed quite settled and happy in his successful literary career. And sulky? When things did not go right for Mr. James, like that morning when Mrs. Paddington kept interrupting with one household problem after another, I had seen him annoyed, but with good reason. I could imagine him as a good, devoted friend but not as a flirt, not as a jealous lover. I was quite sure that, at age sixty-four, he must have been too old to feel any of that.

That afternoon tea was my first such invitation, sent by a Mrs. Dew Smith, a friend of my old friend Nora Wilson’s family—and therefore she was probably very rich and very well-placed. I wanted to make a good first impression, and part of me was also nervous about the possibility of meeting my august employer there; it might be the first time Mr. James and I would meet socially, outside of our working arrangements.

I carefully chose my deep blue cashmere because it was almost clean and the colour would set off my eyes. I laughed to think of Mr. James noticing the colour of my eyes—Had he ever yet really looked at me? I hoped to impress him that I, too, could be a part of Rye’s social scene and prove to him that I was more than the body behind the typewriting machine.

As I walked down the hill and across town, following Mrs. Dew Smith’s instructions, I felt again the conflict between my two sides—hard, ambitious, and practical or tender, creative, and passionate. Which was I?

What was I doing in sedate little Rye, pretending to Mr. James that I was a competent, self-possessed working woman, quietly and calmly sitting before him at his typewriting machine? What did he know of me? Only what Miss P. had told him, and what did she know? I had hidden my wild nature from her as well, combed my unruly hair up into rolls and pins. I had worn a tidy skirt and shirtwaist to work in her establishment and had kept to myself, never talking with her about my real life with my friends, Nora and Clara, reading each other’s writing, sending off our hopeful stories and poems signed with made-up names.

As I had learnt from Mr. James’ prefaces, he prided himself on his sensitive consciousness and might have missed nothing in his apprehension of other people, but I liked to think that I had fooled him, at least before that afternoon.

When I arrived at Mrs. Dew Smith’s, I could see that her house was big and appallingly new, on the Romney side of Rye with a view of the yachts and the golf course. Apparently she had plenty of money and did not mind showing it off. I arrived a little early—Well, I was exactly on time, but that was early for what we used to call a tea-fight. I introduced myself to my hostess. She was full of gossip about our mutual acquaintances, Nora’s parents, and I was glad I did not have to make much explanation of my employment, of what had really brought me to Rye.

Looking around the room as more women arrived, bedecked in their lace and feathers, velvet and ruches, I did not see any others who looked as if they had ever heard of the New Woman or of working for a weekly salary. Mrs. Dew Smith chattered on and filled all the space, and when others came in, I could move away gracefully.

I was glad the constraint of meeting my hostess was over and I could hang back, for timidity had overcome me again like a huge wave and I was floundering beside the tea table, hoping my cup and saucer would not slip from my hands, wondering how to juggle the sandwiches, biscuits, iced cakes, napkins, little plates, tiny forks, sugar tongs, and all the other paraphernalia of the tea table spread before me.

I heard that familiar voice first, then saw that Mr. James had come in soon after the crush had reached its height. Our hostess was clearly thrilled with his presence. She rushed across the room, her shrill voice blaring her pleasure. With pride, she brought him through the crowd, introducing him wherever it was necessary, though I noticed it was not often necessary, for he knew so many people. The slow procession was making its way straight to the tea table—and me—and my hand began to tremble. Would he make a fuss, embarrass me, shame me? Or would he not acknowledge even knowing me and shame me even more?

I put my cup down with a rattle and snatched up a sandwich and bit into the cold cucumber, the smooth creamy mayonnaise, but then the dryness of the white bread was too much. I could not swallow, and then he was there before me. I secretly wiped the mayonnaise from my fingers on the table cloth, knocking several of the biscuits to the floor. I gave one a little kick to send it farther under the table in the nick of time.

But as Mrs. Dew Smith began to pronounce my name, Mr. James took my hand with a great friendly roar of laughter. He was clearly glad to see me, surprised, and yet not totally surprised, all the while keeping my hand in his and easing all discomfiture.

“Ah, yes, my dear Miss Bosanquet, how wonderful that Mrs. Dew Smith should have invited you as well, and we can meet this way. Now, I hope to hear some of your words for a change. You are so efficient and steadfast in our work, listening to mine,” and he paused, waiting for my reply.

Of course, now that I was to answer, I was choking and could only sputter and mumble and nod in a friendly way, but he let go of my hand and went on, turning to our hostess, covering my embarrassment, my gulping of tea, swallowing.

“I feel so blessed to have Miss Bosanquet with me. I was struggling with this project, could not find the right sort of assistance, and a very old, very dear friend brought us together—” Mrs. Dew Smith nodded encouragingly as he went on, telling her all about his enormous, ambitious project of revisions.

I was glad he had been so friendly towards me, but I was a little startled, too, at the picture he painted of his long relationship with Miss Petherbridge, but then I realised they must have long been old friends in some way for him to accept me as unquestioningly as he had. While he continued talking, Mrs. Dew Smith piled up an ample plate for her famous guest and led him to a large comfortable chair near the other worthies of the town, between the short, red-faced man I knew to be the mayor and a handsome young sportsman, who apparently was visiting, from the look of his golf-course plaids and casual air.

I happily swallowed another gulp of my tea, feeling quite pleased that Mr. James had shown his friendship for me and that I had not been required to say anything.

“That was a close call,” a young woman said from the corner nook behind me.

I turned and saw Miss Bradley, tall and blonde, with large dark eyes that took in everything. I had met her several times at her parents’ intimate afternoon teas. I nodded, and she went on.

“You know, he’s quite sweet when you’re used to him, but I remember that my first conversation with our local famous man was terrifying. I was a little girl when he would come to our house and talk and talk. I was afraid he wanted me to respond, but now I know he only means to be kind and to make everything go well. Mr. James has long been an old friend of my father.”

Miss Bradley standing there before me—a vision she was—gestured towards an old gentleman who had replaced the golfing youth sitting near Mr. James.

“My father and Mr. James can talk Shakespeare for hours.” She turned back to me. “I’ve known Mr. James all my life. Miss Bosanquet, ah, Theodora, or should I call you Dora? Oh, why don’t you just call me Nellie?”

And so, we began an easy conversation, so easy that I was comfortable even when Mr. James came back to talk with us and refill his plate and cup.

“Miss Bradley,” he said, “you are back from your studies in Paris, I see.”

“How good of you to remember. Yes, I am home again.”

“And how is your painting? There is so much to see here in our lovely Rye—the old houses, the water, the light—Ah, our sky has been ‘done’ so many times. But I’m sure you bring us the latest techniques. I hope for your father’s sake, that you’re home to stay.”

“I want to stay—If only I can find a proper studio, where I might give lessons.”

“Ah, yes. I have such happy memories of my own youthful painting days back in America at the side of my artist friends so many years ago. Oh, you must find your own place, mustn’t she, Miss Bosanquet?”

He turned to me for support, and happily I found my voice and spoke of the places I had seen in Chelsea, the studios and rooms my friends had set up, and the women whom I had seen painting, sculpting, even writing there.

Our conversation went on easily, openly, for somehow Mr. James made opportunities for me to speak, and my restraint disappeared. I was entranced by the lovely Miss Bradley, and it seemed Mr. James encouraged our friendship, even promising not to work me so hard so that I might have more time for visiting. Later, I wondered if perhaps Mr. James had known what I needed to make me happy—a new friend, the possibility of friendship.

Mrs. Blomfield came over and was introduced, and Mr. James seemed so casually to remark, “I hope you find a chance to show my young friend your lovely home at Point Hill. I shouldn’t spoil the surprise, Miss Bosanquet, but when you do visit, I hope you’ll pay special attention. Perhaps you may see something that will interest you after we begin the next preface, the one for ‘The Spoils of Poynton.’” With that, he turned away to speak with our hostess, who had brought over one last offering to his altar.

In a low, conspiratorial tone, Nellie Bradley admitted that she had never heard of that most interesting novel. “Now, I can tell you. Actually, I’ve never heard of any of his stories or novels. I’ve never read a word. I don’t like to read, but I do like to be read to while I’m painting.” She paused meaningfully and then added, “Perhaps some afternoon you might come to me?”

And so, we made the arrangements.