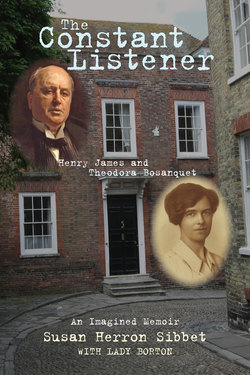

Читать книгу The Constant Listener - Susan Herron Sibbet - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

“The Awkward Age”

December 1907

. . . the quite incalculable tendency of a mere grain of subject-matter to expand and develop and cover the ground when conditions happen to favour it.

—Henry James

Preface to “The Awkward Age” The New York Edition, volume 9

A telegram from my aunt Emily arrived, announcing she was to arrive in Rye the next day. She said she happened to be visiting with a friend and hoped to come over to spend the afternoon. Mr. James had asked for an entire morning’s work. That meant that the afternoon would be mine, and I could take her to all the sights in Rye. But, oh dear, she wanted to meet Mr. James and see where I was working. I could not have that happen. He would seem such a strange sort of person for Aunt Emily’s niece to be spending time with.

Aunt Emily had always held high aspirations for me. Oh, not marriage and social position as the other aunts on my father’s side did. No, Emily was my dearest aunt, my mother’s sister-in-law. And I think I was always her favourite, too.

I am not sure why I was special to her, because I was the wildest of all the cousins. Perhaps she liked me because I had most needed her help, or perhaps it was because I was quite different from what was expected. But whatever the reason, my aunt Emily always took notice of me, though I do not believe she understood me any better than any of the other aunts did, and there were plenty of other aunts, all of them aunts by marriage. My mother had only suitably business-minded brothers, six of them. They all were married, and Aunt Emily was married to the youngest, my uncle Ras, and lived in a big house in Kensington. As much as she liked me, not even Aunt Emily seemed to understand what I thought or cared about, even while I was young and still living with my father. No one understood why I enjoyed repairing bicycles. And I am sure that no one at home ever read one of Mr. James’ novels, for they hardly read any books at all.

“Home”: What a strange-sounding word now, after all these years settled in London with Lady Rhondda—my Margaret—and with the Second Great War more than a decade behind us. Where was my home then, in those days when I first went to Rye? I was startled then if Mr. James suggested I go home on the days when his struggle to find the right words overcame him, when it appeared to me that he had spent too much time away from his dictation and had lost the thread.

Even then, I thought it strange to call my boarding house and its cramped, cold room “home.” When forced to return home to that room, I was miserable; it was noisy and through the thin walls I heard voices, but those were voices of no one I knew or wanted to know. I felt quite lonely there. On cold winter days, that room was dark and even damp, and the old wall-paper was yellowed, greasy, while the one low-browed window opened only onto an unkempt patch of grass and the alley with its cans for cinders and rubbish.

When I was young, I used to have a lovely room in our old, brown house across the road from my grandfather’s big house filled with Bosanquet uncles and aunts and cousins in Swansea, the older, more fashionable part of the Isle of Wight. My father was the youngest boy of eight. His eldest sisters, my aunts Bessie and Bert, were much older. I am sure they never approved of me, especially when I wanted to go to university, for they had very definite ideas about what a young lady—a well-behaved young niece—should be, and whatever that was, I was not that. I wish I had met my father’s younger sister, Georgie. She was most unusual. I had always heard that she’d never married, wore her hair cut off very short, rode horses, raised dogs, and was not at all like the other sisters. But she never came to visit.

At first we lived near my Bosanquet grandfather, and I grew up believing the Bosanquets to be the busiest, most energetic of families, with our golf games at dawn, cricket before luncheon, croquet tournaments in the afternoon heat, and tennis round robins at tea-time.

My father was happy and busy in those days, when he was assistant vicar in a big, popular church. I don’t remember his being at home often, fortunately not enough to notice much about me. I was an ungainly girl afraid to make many friends. My older cousins across the road, Queenie and the boys, fascinated me, but often they were busy, and so I would read or play alone with my cats; we always had two or three feline generations, mother and daughter and granddaughter, and they were my best friends.

My mother and father liked it best when I was quiet. When my father was home, he was usually doing something in his study, and my mother was often in her room with the door closed. She always rested after lunch, every day of her life, a real rest, not a few minutes of sitting down with her eyes closed. No, she went up to her room (and of course she and Papa never slept in the same room in those less-demanding times) and had several private hours without interruption. By unspoken agreement, the household protected her. Everyone told me to keep quiet and be good; even then, my mother’s health was not strong.

Her room was cool and dark in the early afternoon, even in summer. She had the shades drawn and the curtains closed, doubly dark there in her cave of shadow and bed and dresser. She always slept under a cover of some sort, a soft knitted pink blanket in winter and, in summer, the most beautiful coverlet—crisp and white, made of embroidered linen and lace, an impossible dream of a bed cover. When I was young, my mother seemed to me a very silly woman, but I understand, now that I am older than my mother was when she died, that she wanted only to have beautiful things always around her, that she wanted her life to be beautiful, too, and so she made a little ritual, I realise now, of going up to her darkened room at the same hour every day.

“For a little bit,” she would announce at the luncheon table. “I’ll go up now for my little rest, for a few minutes. I always feel so much better after I’ve had my rest. Please forgive me. Perhaps you both should take a rest as well. I think it’s best for us to save our store of energy, while we can,” and so, with a coy wave, up she would go.

I always felt a little lost when my mother was sleeping in the middle of the day. I had too much energy to lie down at midday when I was young. The maid could not persuade me to stop playing and rest for a few minutes even if she promised to look at a picture book with me, but once I was old enough to read for myself, I would take my book and disappear outside, and no one could pull me back, even for meals. And then when I got my first bicycle, oh heavens, I was free at last to go wherever I could imagine, flying down those sandy lanes, my long legs out on each side, my short hair loose, blown back by the breeze I had created.

Though I understood even then that my mother was not well and needed rest to save her energy, nevertheless, her door was closed all too often when I wanted her. There were some good days when she would be in her sitting-room by the window, writing letters or painting with a tiny brush some water-colour scene on stiff paper the size of my hand. She and Papa wrote and illustrated a story book for me, a rhyming version of “The Three Bears,” but it was such a strange little book that I was afraid of it, I think. I did not like how it portrayed what happened to bad little girls. Goldilocks looked terrified by the huge bears, and even the youngest bear frightened me when his little wooden chair burst under him, with the sharp splinters flying everywhere, the way my parents drew the story. I guess they thought I would laugh at his predicament. I don’t think Mama ever understood my fear of meeting strangers, or of the dark, and so I had to pretend to be strong and brave for her. No matter how hard I tried, I could never be the good little girl my parents had wanted.

Sometimes, though, my books would not be enough, and I would escape that quiet house to go across the road and find my cousins. I thought I must be a bit of a Bosanquet after all because I did like to run outside and play games, especially with my boy cousins, especially cricket, which was their favourite, too. Because I was tall and strong and fast, they always let me into their games. We felt that playing cricket was our birthright, for, as Bosanquets, we were extremely proud of being related to our famous cricketer cousin, T. A. Bosanquet, whom we admired much more than our philosopher cousin, Bernard Bosanquet.

As we grew older, the boy cousins became more uncomfortable when I came out to play, but I always believed that it was because I had grown taller and was faster than they were. I was proud of being chosen to be on my school teams, but my strength and fame at cricket only seemed to embarrass my mother. I remember her scolding me for rips in my play skirts and grass stains on my knickers. She would worry that I was playing too rough and too wild for a proper sort of girl. I tried to reassure her by bragging that they loved what I did at my school. Even Cheltenham Ladies College, the bastion of propriety and wealth that the family had packed me off to, could be happy with such an excellent cricket player.

But then at the end of my first year, when I came home from Cheltenham, I found things to be very much changed. My family had left our beautiful big brown house, left our cats and cousins, and moved to Dorset and a new house, the Hermitage it was called, and a new parish, Uplyme. My mother seemed even more tired, and there was a new baby brother.

They never explained to me what had happened, why the birth had been so difficult. Now, I wonder if perhaps my mother was too old. My parents always seemed old to me, and they had waited for a long time, even for me, and I was already ten when Louis was born. Perhaps something had gone wrong, for my mother was never well again, and poor little Louis—We all felt that there was something not quite right about him. Our house had to be kept absolutely quiet, for once the baby began to cry, there was no way to comfort him. We went through a succession of nurse-maids and other servants, who did not want to stay on. Louis was always the most beautiful and the most difficult child. Perhaps I did not help much either, since I moped about the new place, complaining, wishing to be back at my grandfather’s, back with my friends at school, anywhere but there.

In that regimented quiet, once again I found my only freedom in books. I read all the time, so that my parents could not say I was making too much noise. Instead, days would go by when no one heard a word from me.

I think it was like that, too, when I went to Rye, far from my family and friends once again. No matter how lonely I felt, I could still lose myself in books and, this time, in Mr. James’ library. As he looked over my shoulder, he saw me finishing book after book, and he would even suggest what I should read next, so that I might go ahead to his new stories, or look at a play he was going to revive, or even go back and see what his newly dictated prefaces were like. I was happy to think I had more, new, unpublished writings by Henry James to read.

After all this time, I can still remember the shock of pleasure I felt as a young girl when I read my first James story. That was one night when a more experienced girl at Cheltenham smuggled to me that strangely affecting ghost story, “The Turn of the Screw.” I remember turning the pages, slowly at first, mystified, then hungrily devouring the book, and eagerly seeking out all the rest—novels, novellas, stories, everything. When I had to leave school because my mother was very ill and needed me at home, I was glad I had books for comfort.

My mother was taken from us when I was twenty. It was Aunt Emily, her brother’s wife, who came to help. I think she must have felt sorry for me, a young girl left alone with a small brother and a bereft father. Of course, I thought that I was grown up then; after all, I had been in charge of myself and of our household for the long months of my mother’s illness. But I remember that during the time the different aunts stayed on with us after the funeral, it was Aunt Emily who could make me cry—her voice sounded so much like my dear mother’s—and she tried to comfort me, something my father never tried to do.

It was also Aunt Emily who was there and who knew what to do when I fell ill. A bad head cold suddenly turned terrifyingly worse—high fever, headaches, and then my ear was in excruciating pain until suddenly, with a feeling of intense pressure, then release, my eardrum burst. I was ill that time for several weeks and needed Aunt Emily to take care of the household and keep me from complete despair, but as things do, I got better, and she could return to her own family.

The next year, when I went to prepare for the exams for university, only Aunt Emily listened to me talk about what I was about to do. I wondered if she wished that she herself had gone to university, but of course when she was young, there had been no real opportunity. After I received my degree, I think she was proud, though of course she never said so. She only glanced at the piece of parchment I had tacked up on my bedroom wall; she touched the Latin words, then went on talking of her garden and the weather.

It was against my father’s wishes and the other aunts’ dire warnings that I shared a flat in London with my school friends and went to work with Miss Petherbridge in Whitehall. Even that outrage did not seem to faze Aunt Emily. She would invite me to dine with her and my cousins at Honiton Street, and though she never asked about my work and I never really spoke of it, I am sure that she knew. Her present for my birthday that year was a very smart leather belt, with a note indicating that I was to use it to look handsome when I was on the job. I was very pleased that she might approve of me, because all the other aunts were in a dither over my working at all. They were at my father like a flock of sparrows, but of course he did nothing, said nothing; soon enough, he had his new bride and their new house. My father was the last person to be concerned about me, about what work I was doing or even where I was living. Even before I was twenty-one, when I left to go to university in London, he informed me that I was to be on my own since I was so smart. From then on, I would have to make do with my mother’s inheritance; once he re-married, he and Annie would not send me any more funds.

Now, all these many years later, I see why writing this is so difficult. I can’t seem to stick in one place. I keep wanting to write as if I am talking to someone, but that feels too personal. I am afraid there are things I should not be saying, afraid there are people I will hurt, even though my father has been dead now for thirty years, and my poor dear aunts have been dry and dead even longer. My cousins, even the youngest ones, Queenie’s children and the others, have long given me up. I believe they think I am stranger than even my aunts thought; they whisper about me across the cocktail table whenever I attend family gatherings. So what do I care if I tell things that might hurt people’s feelings? And what do I care if I tell the truth? But I do care that it makes sense. I do care that I tell it well, and not this haphazard sort of unstructured writing—I suppose I can always return later and clean it up, but that was not the method I learnt at Mr. James’ knee, or should I say, at his elbow.

I did not mean to be writing about my father or even my aunt. I meant to be writing of those first days with Mr. James and how what I was doing there was unusual for a young woman, but now, all these years later, who could understand that? These days, young girls go into unrelated older men’s houses and do all sorts of things every day and night, and no one thinks anything of it. But in 1907, so soon after the Old Queen died, so soon after King Edward, that wild royal, had become the leader of the Empire, well, who knew what to think?

Certainly Aunt Emily did not. And that was why she came to Rye so soon after I began to work for Mr. James. She had decided I needed a family visit. When she arrived, I was still up in the Green Room, trying to finish. I heard the knocker thump, and she was brought upstairs.

“Dora, my dear,” she exclaimed as she took off her tiny brown suede gloves and lifted her fashionably dotted veil to look around, “what a charming place your Mr. James lives in. And how hard you must be working!”

“Aunt Emily! You’ve surprised me!”

The room was strewn about with open books, piles of papers, ink pots, red and black, and I was still rudely sitting at the typewriting machine.

“Let me finish this line,” I said. “You’re so early!”

I went to help her with her things and to lean down to give her my customary kiss on her soft, papery cheek. She was dressed in her favourite colour, that rich cocoa that set off her dark eyes so well. Even after she removed her delicate little hat, her silvery hair was still its usual perfection in its braids and elaborate coils. She smiled, and I thought that her face showed a little tiredness from the journey, for her pleasant smile lines had deepened and her skin was not its usual perfectly transparent rosiness. She was telling me she had caught the earliest train.

“I was that eager to see you, my dear. And we’re all so curious about what it is you’re about here.” She looked around the room with its mess and books everywhere, so different from her tidy, plush-velvet Kensington home. “I’m afraid we’re all worried about your Mr. James, and what it’s like for you here all alone, without friends or family. My dear, whatever were you thinking?”

And so for the hundredth time I had to try to explain to someone, and even worse, a woman from my mother’s generation, what I was doing there with Mr. James. I was not homesick and was certain I would be fine once I was accustomed to the typewriting machine and to Mr. James and his unusual working style. By now, he almost seemed to be more like me than anyone in my family. But I could not tell Aunt Emily that! Looking around his masculine, leathery book-lined study, I could barely speak. My reticence had once again returned.

“Aunt Emily, I’m not sure—I need to work, I need to be on my own. As you know, my father—”

“Oh, don’t speak to me of your father, I’m not thinking about your father. He’ll do fine with that nice new bride to take care of him. No, Dora, it’s you I worry over. What are you doing here? Won’t you come back to the aunts and let us try once more to find you a husband? You know, you barely gave us a chance last summer before you hurried back to London and took a job in that secretarial bureau. Aunt Ellen and I were mortified. Really, my dear, none of our other nieces has ever done any such thing. Even Cousin Freddie when she went down to Swansea to teach in a boys’ school did not surprise me as much. Have we really failed you so badly?”

I knew I had to answer something, for my dear aunt had my best interests at heart, but what could I say? I could not explain how I had come to be there, instead of making the rounds to all the aunts and uncles, repeating the circuit until someone found the right man for me to marry. Well, I knew that would NEVER happen. When I was younger, my deep love for Ethel had made that clear to me, even if no one but my friends believed in me. But how could I tell this dear aunt the things that I had held silent in my mind and heart for so long, for years—a lifetime, it seemed—the things that would disturb her so?

While I was hesitating, Aunt Emily moved around the room, nervously fingering an object here, a piece of paper there, lifting up a book to look at the title by the light of the window, then putting it down with a shake of her silvery head. She turned again to me. “I suppose I’d better come right out with it. What we really want to know—Is it proper, do you think, for a gentleman’s daughter to be here, doing this sort of work? You know we’re not at all familiar with what it is you are doing here.”

I tried once again, explaining my work as literary secretary to Mr. James, helping with his correspondence, of course nothing personal, and then his real work, writing the prefaces, the stories, and the plays.

“Aunt Emily, I imagine as he dictates to my typewriting machine that he is talking only to me, as if I were his friend and we were sitting together over tea. He tells me about how he got his ideas or where he ran into trouble—it’s as if we are partners or old friends. He seems to tell me everything.”

“But Dora, is it proper? Is it right for a young, unmarried woman to be here in a man’s house, alone with him, upstairs, up in his room? I’ve never heard of such a thing!”

I had to think for a minute why it seemed right to me. Of course, I had been uncomfortable at first. It was a small, intimate house and very much arranged for the comfort of the elderly bachelor who lived there, but then I thought back to why I had wanted to work with Mr. James from the first instant I heard about the job.

“Oh, he’s fine, Aunt Emily! Ever since I was a girl, I’ve loved his books. Maybe some things I could not understand, some subject matter was too old for me, and some things I still don’t understand. He is very deep, Aunt Emily. But always I’ve felt that Mr. James had a special gift, a way of making complicated things clear, as if he were writing for me or girls like me. Maybe it would help if I could show you.”

I went to the shelves to look, and Aunt Emily went to sit carefully on a small, old chair beside the writing desk. But first she had to move a book, which had been left there; she turned it over, with its yellow wrapping, its foreign-looking cover and French title, and she put it down carefully without checking inside. Then, looking around, frowning at where my typewriting machine made an ugly shadow on the floor, she folded her hands to wait.

I found the page. “Here, one of his young heroines is talking about how hard it is to grow up in this day and age. You’ve watched my girl cousins and me struggle. Listen . . . Here in this morning’s preface, Mr. James has young women in mind:

“‘One could count them on one’s fingers (an abundant allowance), the liberal firesides beyond the wide glow of which, in a comparative dimness, female adolescence hovered and waited.’

“Mr. James goes on to describe the ‘inevitable irruption of the ingenuous mind’; and then says,

“‘The ingenuous mind might, it was true, be suppressed altogether, the general disconcertment averted. . . . A girl might be married off the day after her irruption, or better still the day before it, to remove her from the sphere of the play of the mind;’

“Can you see, Aunt Emily? It’s as if he spoke our hopes aloud, finding words for us young women:

“‘That is it would be, by this scheme, so infinitely awkward, so awkward beyond any patching-up, for the hovering female young to be conceived as present at “good” talk, that their presence is, theoretically at least, not permitted till their youth has been promptly corrected by marriage—in which case they have ceased to be merely young. The better the talk prevailing in any circle, accordingly, the more organised, the more complete, the element of precaution and exclusion.’

“Aunt Emily, if we younger women can only find our own way, a way out of this ridiculous set of impossible expectations. Can’t you see?—Whenever I read this, it makes me feel that he sees us. He wants to help us, here in our preposterous position, caught between what we want and what is expected. He describes one of us, a young woman of 1907, kept modest and ignorant, and yet she’s still expected to know so much. We’re supposed somehow to stay innocent and yet understand every innuendo, to be good and also wise, to act helpless and yet to be strong, to appear beautiful and at the same time completely artless.”

Aunt Emily had moved uncomfortably in her chair. She did not like my use of “innocent” and its implied, unspoken opposite. She raised her head and protested, “But Dora, the old ways were there to protect the young girl—”

“My point exactly. Now, we are without protection. Everyone claims to admire the New Woman, but then no one knows what to make of us. What do we want? And what does it mean when we’re brought up among such contradictions, when we are encouraged to try for good jobs and independent incomes, then required to give it all up if we ever marry? Or we’re supposed to remain innocent and pure yet can attend university with our brothers and argue about biology and economics, educating ourselves, but for what? For glorious disappointment. And now we have those impossibly idealistic Suffragettes, trying to persuade the public that all women, except the Irish, should have the Vote. They make beautiful speeches with their classical allusions, their goddesses and martyrs and glorious hand-embroidered banners—and all the time they’re divided among themselves as to when or whether they should blow up Parliament. Oh, it’s all so confusing—But I know that when I read Mr. James, I feel safe, I feel understood. Working beside him, I feel useful, I even feel a little like I might somehow learn to understand myself.”

After my outburst, Aunt Emily shook her head, and I changed the subject to ask after the new baby cousins I was sorry to have missed at the holidays. My aunt stayed on to share the tea Mr. James had arranged. I gave her sandwiches and a cup of tea, but probably it was not her usual flavour. I am afraid that the sort of biscuits Mr. James usually provided seemed rather small, and his sharp-flavoured cheese crumbled. I can see her familiar, exquisite gesture as she brushed the crumbs off her delicate fingers with her handkerchief, then folded her hands in her lap and looked around, still silent. In the face of all my words, she was too perplexed to speak.

But later that day, when Aunt Emily had gone and Mr. James had returned from his afternoon away, I realised that something had changed. Somehow, my aunt’s unspoken questions had been answered. It was not by anything I had said, I was sure. Perhaps it was Mr. James’ lovely home, Lamb House itself, with its solid evidence of rank and presence and position, that reassured her. Before she left, we took a turn up and down the gravel paths of his walled, formal garden and looked at the neatly labelled beds of perennials, the prize-winning rose-beds, and his awards (earned by his gardener, George!) proudly hung on the wall of the glass house, each medallion engraved to “Mr. H. James, Esquire.” There, in the cool winter afternoon’s light, surrounded by the grey stone and ancient pale-rose brick walls, everything was orderly and snug in Mr. James’ well-tended and protected winter garden.

And so, my aunt left me with a long hug, pressing a specially wrapped package into my hands, insisting that I open it after she had left. It contained several of her large, and justly famous, plump currant scones along with her hastily written note explaining that I was to share the scones with my employer.