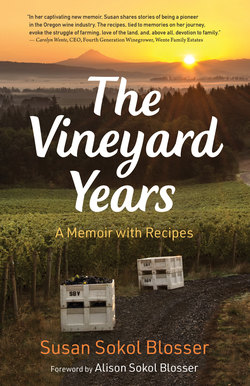

Читать книгу The Vineyard Years - Susan Sokol Blosser - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Mac & Cheese Days

In the last two weeks of 1970, my husband, Bill Blosser, and I each gave birth. I had our first child, Nik, and Bill closed the deal on our first piece of vineyard land. We were together in our excitement about both, but since the vineyard began as Bill’s passion and I was utterly alone having Nik (fathers at that time weren’t allowed in the delivery room), I think of them as one birth for each of us.

Baby Nik actually had a longer gestation period than our land purchase. The idea of a vineyard seemed to arrive out of nowhere, a bit of whimsy that took on a life of its own. We were driving our Volkswagen camper bus from Chapel Hill back to Oregon, where Bill was to teach urban planning at Portland State University. Near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, we stopped to browse at a flea market. It was Pennsylvania Dutch country, and we thought we might find an antique treasure hidden in the junk. We meandered through with the other bargain hunters and, somewhere in the midst of tables laden with wooden clocks, rusty fruit bins, and old kitchen utensils, Bill started talking about starting a vineyard. He later confessed he had been thinking about it for some time and finally had enough nerve to bring it up.

“What do you think about growing grapes?” he asked, as we bent over a particularly handsome mantel clock.

“Grow grapes?” I asked. I turned to look at him. “You mean to make wine?” His question—unexpected and unconventional—startled me.

“Why not? I think it would be a neat thing to do.” He sounded a bit defensive and I understood why. It was a wild, improbable idea.

We lost interest in the mantel clock and headed back to our camper. All the way back to Oregon, this outlandish idea kept coming up. We’d drive along in silence, listening to whatever local radio station we could get, and suddenly Bill would bring up the subject, again. I listened, wanting to be a supportive wife, and the more we talked about it, the more interesting it became.

We both liked wine. Bill had spent a year in France during college, taking classes in Paris and then working as a dishwasher at a mountain resort near Grenoble. He had emerged from that experience a wine-drinking, French-speaking Francophile, with a worldliness that had attracted me to him in college. I had spent the summer after high school studying in France, and I had grown up drinking wine from my father’s wonderful wine cellar.

The idea of going back to the land and growing something that made life more enjoyable appealed to us. We would never have been attracted to soybeans or corn, but growing wine grapes had both aesthetic and emotional appeal. Wine symbolized culture and sophistication. People had been making wine for centuries—how hard could it be?

Really hard, as it turned out. The arrival of our two new babies determined the direction of our lives from then on. In our mid-twenties, we had been married four years, and had spent most of that time in graduate school, first in Oregon for my Master of Arts in Teaching from Reed College and then in North Carolina for Bill’s Master of City and Regional Planning from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. We had studied hard and played hard.

Our 1968 Volkswagen camper bus, a miniature house on wheels, had carried us all over the continent. We hiked and picked wild huckleberries in the Mount Adams Wilderness in Washington State. We camped near Old Faithful at Yellowstone National Park and fled, early the next morning, singing loudly to scare off a nosy grizzly bear that had appeared during the night. We drove to Lake Louise and across the wheat-colored plains of Saskatchewan, fighting headwinds that held our boxy vehicle under forty miles per hour. We explored the entire Blue Ridge Parkway of Virginia and North Carolina, sleeping in the bus and cooking over campfires, stopping only for supplies and a new block of ice for our tiny refrigerator. With no kids, no pets, no house to worry about, we never hesitated when another trip beckoned.

Summers in Chapel Hill, we played tennis every evening, waiting for the muggy heat to retreat before we went out. Winters, we tried out complicated recipes from Julia Child’s new cookbooks. We judged the recipes by how long and involved preparation was against how much we enjoyed eating the finished product. Over elaborate dinners with the other student couples, mostly Northerners like us who were fascinated with Southern culture, we discussed politics, civil rights, and feminism. We protested the Vietnam War and drove to Washington, DC with friends to join the candlelight vigils and marches.

When the baby and the vineyard arrived, life abruptly changed course. Road trips, camping and hiking, tennis after dinner, spontaneous parties—all these became memories. After a few years, I started to think of them as a past life.

Back in Portland, we found a house to rent and began researching the geography, soils, and climate that wine grapes required. We had celebrated our engagement at a picnic on the grounds at Beringer Winery in 1966, but locating in Napa didn’t interest us. Other parts of northern California might be possible. On a visit to Bill’s folks in Oakland, we scouted for possible vineyard sites around Ukiah and Mendocino, where Bill’s family had homesteaded in the 1850s. Northern California could be the place for us, but we continued looking.

Driving through Oregon’s Willamette Valley countryside one Saturday, we stopped at a one-room real estate office in Newberg to inquire about land. It was useless to ask directly about vineyard land back then, because real estate agents had no idea what that meant. Bill was describing the kind of land he was looking for, in terms of slope and exposure and soils, when the agent said, “See that guy over there, looking at the book of listings? He just asked me the same question.” That guy, Gary Fuqua, was soon to plant one of the earliest vineyards in the Dundee Hills and become one of Bill’s best friends.

The real estate agent, shaking his head at what crazy things people wanted to do, tried to help. “Have you talked to the guy up on Kings Grade Road?” he asked. “A big friendly guy. He has just planted a vineyard and seems to know what he’s talking about.” Following the agent’s directions, we found the ramshackle house where Dick Erath, his wife, Kina, and their two toddler sons were living. Dick had bought the property and planted vines in 1968.

But Dick and Kina had not been the first, either. Two other couples, the Courys and the Letts, had bought land in the Willamette Valley a few years earlier. Dick and Nancy Ponzi had also just bought land. These four couples were working regular jobs, living as cheaply as possible, and putting all their extra time and money into their vineyards. Finding them inspired us to keep going; we were not alone.

These founders of the Willamette Valley’s wine industry, plus those who, like us, came shortly after—Myron Redford, David and Ginny Adelsheim, Joe and Pat Campbell—stood out with their quirky individuality. Scruffy sideburns, beards, and mustaches aside, they were smart and enterprising, finding various paths to wine, discovering it as a passion and changing course to pursue it against all odds. With diverse backgrounds in engineering, music, philosophy, history, and the humanities, coupled with a fierce spirit of independence, we were united in a passion for Pinot Noir. We were trying something that hadn’t been done before and we eagerly shared information. The collaborative nature of the Oregon wine industry became one of its most notable features. Did any of us anticipate that our youthful adventure would create an industry that would, in one generation, add over two billion dollars to the Oregon economy? I surely didn’t.

In the early 1970s, it was a boys club. And an interesting group of boys it was. Dick Erath brought his engineering mentality and love of science to the table, spending long hours researching grape clones, trellis systems, cultivation methods, propagation systems, and the like. He always had a hearty laugh and welcomed everyone into the industry, just as he had Susan and me. Dave Lett was something of a hermit, not really liking committee work or lobbying, but he was deadly effective in marketing and was an early supporter of tough labeling standards and land use laws. Dave Adelsheim was one of the easiest possible people to work with and had a keen perception of what was needed to develop a lasting industry, from labeling laws, to the grape tax, to marketing programs, to being a key player in the establishment of the International Pinot Noir Celebration. When we needed an effective diplomat to solve a knotty problem, Adelsheim was the man.

Bill Blosser

Cofounder, Sokol Blosser Winery

Like most of the other couples, neither Bill nor I had any business experience. We hadn’t even taken a business class in college. That didn’t stop us; we could learn. No tradition of fine winemaking in Oregon? We would create one. We knew we could lose everything, but none of us had much, so that was no deal killer. Our college professors had touted a liberal-arts education as training for life—we could do anything with it. Planting wine grapes in Oregon represented a risk most easily made by people in their twenties, an age when optimism has not yet been tempered by experience.

To prove we were not entirely crazy, we would point to the master’s thesis Chuck Coury had written at the University of California, Davis, in which he showed that the climate of the Willamette Valley was virtually identical to that of Burgundy, whose Pinot Noir wines were world-renowned.

Bill and I wanted be part of this great Oregon experiment of growing Pinot Noir, the Burgundian red grape with a reputation for being difficult. We focused on planting a vineyard. Starting a winery seemed so far in the future, we never talked about it. The immediate challenge before us would be figuring out to how grow wine grapes in this new, untested region. If we succeeded, it would take all of our smarts as well as our physical strength and stamina.

After looking at possible vineyard sites in the hills of the northern Willamette Valley, we found what seemed the perfect piece of land in the Dundee Hills, about thirty miles southwest of Portland. The area, known for its giant, sweet Brooks prune plums and hazelnuts, is a series of gentle hills ranging from three hundred to a thousand feet in elevation. Our eighteen acres, at the five-hundred-foot level, had been an orchard, destroyed by the Columbus Day Storm, a powerful windstorm famous for its devastation. The old prune trees sprawled across the land in haphazard fashion, few still upright. Local lore was full of stories of the damage and death caused by that tempest, which we assumed had happened recently because it was such a common point of reference for local farmers. We were shocked to learn that it had occurred in October 1962, almost a decade earlier. The stories told with so much immediacy showed the long-term impact of weather on a farming community. We weren’t deterred. Perhaps because we hadn’t lived through its ferocity, the storm seemed a remote, one-time event.

The old orchard had been waiting for us, the downed trees obscured by a labyrinth of blackberry vines and common vetch that had blanketed the hillside over the years. Knowing that fruit trees had once flourished, and that Dave and Diana Lett’s new vineyard was just down the road, cinched our decision to buy the land. Even with our limited knowledge, we knew that the presence of an orchard meant the hillsides would be frost-free in early spring when those trees blossomed and thus would be safe for grapes, which leafed out at the same time. We bought the land for eight hundred dollars an acre and hired a local farmer to clear it. It had been just five months since the subject of a vineyard had first come up.

From the beginning, the vineyard was Bill’s baby. I mirrored his excitement and didn’t want to disappoint him, but it was years before I experienced the passion that he felt from the start. I didn’t flinch at the challenge, the commitment, or the money we put into the project. But it took time for me to feel that it was a genuine partnership.

Our rented house in southwest Portland, so far from our property, became increasingly inconvenient. With Bill teaching at Portland State University, we had only weekends to work the land. We found a farmhouse to rent about a mile from our property, and our family—Bill and me, baby Nik, and our cats, Cadwallader (Caddie) and Tigger, moved there in May 1971. The house had a long, narrow front yard ideal for rooting grape cuttings in nursery rows. The small bushy plants would then be planted as dormant rootings the following spring.

California, with its nascent wine industry, was then the only source for wine grapes, so when Bill visited his folks in Oakland, he and his dad drove to Wente Vineyards in Livermore, hoping to buy some of Karl Wente’s certified, virus-free Chardonnay cuttings. Bill was thrilled when Karl himself greeted them warmly in his small office. “Gonna grow grapes in Oregon, eh?” he said. “Great idea. I always wondered why no one was trying the cool-climate grapes farther north. I think you have a chance to make some great wines up there.” These words of encouragement from a successful third-generation winegrower further motivated Bill. He and his dad returned home with cuttings of all the varieties we thought might grow in our cool climate—Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, Riesling, and Müller-Thurgau (a cousin of Riesling). Bill always remembered Karl Wente’s welcome and encouragement, but never saw him again. The great man died suddenly at age forty-nine, six years later.

The big white farmhouse we rented sat beside the old state highway, a picture-book place with its tall, shady trees along the front and old, untended cherry and prune orchards along the sides and back. But any romantic notions we had about country living quickly dissipated. From across the narrow road, one of the area’s major turkey farms assaulted every one of our senses from the day we moved in. Hundreds of white turkeys lined up at the fence to clamor at us, red jowls bobbing and beady eyes staring. From time to time huge trucks went by carrying stacks of large cages crowded with turkeys. White feathers floated to the ground long after they had passed. The odor of turkey manure, ranging from pungent to gagging, depending on the heat and wind direction, maintained a constant presence. The gentle breeze that cooled me while I worked in the vegetable garden also enveloped me in the rank smell of turkey.

Bill and I had often talked about what fun it would be to buy an old farmhouse and fix it up. Realizing what it would take to make our rented farmhouse comfortable ended that fantasy. We were told that our house, like a number of others in the valley, was the work of some barn builders who came through in the early 1900s. They built houses the way they constructed barns—framing studs set more than two feet apart, little attention to detail, no insulation. My homemade cotton curtains fluttered in the wind even with the windows closed, and the smell of turkey manure leaked in through the cracks. Over the years, residents had added sections to the original house, so that by the time we moved in, what had once been an animal shed in the back had become part of the house.

The cats roamed freely through the abandoned orchards, sleeping by day, hunting by night, and wreaking havoc on the mouse and gopher population. After Tigger was run over one gruesome night, Caddie did the work of two. She was a fearsome hunter and ate most of her prey outside, leaving the front teeth, whiskers, and large intestine on the doormat to show us her prowess. But occasionally she thought they’d taste better inside; one night she leapt up and came flying through the open window above the head of our bed. I opened my eyes in time to see Caddie, clutching a giant gopher in her mouth, pass over me, inches from my face. I listened to her chewing her prize for a few minutes, and then turned over and went back to sleep, making a mental note to watch where I stepped in the morning.

For the first few months, until the cats pared down the population, the mice were the most active inhabitants of our house. I learned to put my feet in my slippers slowly after once feeling a living fur ball cowering in the toe. When my mother visited from Wisconsin, I sat with her at the kitchen table trying to keep her engaged in conversation so she wouldn’t see the mice scampering across the floor. She turned and saw them, of course, as soon as I stopped talking to take a breath. They only reinforced her belief that Bill and I were living in the wilderness. She must have enjoyed herself anyway (or else felt I really needed help), because by the end of the decade she and my father had moved to McMinnville, seven miles from us, where they spent the rest of their lives.

Our house stayed warm because we kept the huge brick fireplace in the living room going fall, winter, and spring. We had plenty of firewood from downed trees, and a big fan in the fireplace sent waves of heat through large vents to warm the rest of the house. We splurged on new carpet for the living room, a gold shag found at a discount warehouse. Shag was in fashion, and we bought a special rake to make the long threads lie in the same direction. But even with the carpet neatly combed, the place was never more than tolerable. We were near our vineyard and the rent was only a hundred dollars a month, so we put up with it.

As an urban girl, my gardening experience had consisted of growing a sweet potato propped on toothpicks in a glass of water, a grade-school science project. In Oregon, surrounded by fruit trees and plenty of land, I felt compelled to have a vegetable garden. I went wild with the Burpee seed catalog, inspired by page after page of captivating photos of pristine vegetables. The seeds I planted would surely grow into that picture-perfect produce if I followed the instructions on the seed packets. But did “plant in full sun” mean I should plant the seeds on a sunny day, or in a sunny spot? One gardening book advised, “Harvest during the full moon.” Should I pick my vegetables under moonlight, or could I pick them in daylight if there was to be a full moon that night? I laugh now, but at the time I was genuinely confused.

That first spring, after savoring the catalog descriptions all winter, I planted everything that looked interesting, from peas to pumpkins. I kept the growing season going right into fall, but I was way out of my league. Overwhelmed by the successes—I’d never seen so many zucchini—I was also befuddled by pest problems. I had no idea whether the cute little bugs I saw crawling around the plants were going to help me or destroy the garden. I knew ladybugs were good, but how about the ones with black spots that were yellow instead of orange? Captivated by the wonder of working with the earth, I came back every year with a little more knowledge and renewed hope. My garden taught me that every year gave me another chance, the secret to a farmer’s optimism.

While our grape cuttings in the front yard sprouted leaves and roots, we searched for vineyard equipment we could afford, which meant it had to be secondhand. The weekly agricultural paper listed the farm auctions and used equipment for sale everywhere in the valley. We needed a tractor and other equipment, so Bill and I, with Nik in the backpack, attended farm auctions almost every weekend. When we found the right tractor at the right price, an early 1960s Massey Ferguson orchard model, we happened to be at an auction at the other side of the valley. The only way for us to get it home was for Bill to get on the tractor and drive it. As he bounced along country roads in the open air at less than fifteen miles per hour for the two hours it took to get back, Bill didn’t need my sympathy. So proud was he with our new purchase, he confessed he felt like a king piloting his carriage. Nik and I rattled along behind him, in case the old tractor broke down, in our ’54 green Chevy pickup, which we called Truckeroonie.

Truckeroonie had been Bill’s first vehicle, bought while we were at Stanford. Despite a two-year rest while we were in Chapel Hill, it was feeling its age. Bill commuted to Portland in the VW camper, so when Truckeroonie broke down, I was at the wheel. I learned never to go out in it without rain gear, rubber boots for walking in the mud, and a backpack for Nik. I will always be grateful to Hank Paul, the local mechanic in Dayton, the nearest town, who got used to my sudden appearance in his shop. His scruffy little white dog, with the shaggy hair over its eyes, always scampered out to greet me. Hank would stop what he was doing; Nik and I would climb in Hank’s big pickup, with the dog; and we would drive back to wherever Truckeroonie had stalled so Hank could get it going again.

With its old green cab, worn leather seat, and long wobbly stick shift, Truckeroonie had taken us camping in the California redwoods country, where we had slept under the towering trees, and to the San Francisco Opera House, where we had watched Rudolf Nureyev make jaw-dropping leaps across the stage. Truckeroonie was our transportation, whether I wore dirty jeans and hiking boots or a slinky black dress and high heels. One day, Bill came home with a shiny new sky-blue pickup. We sold old Truckeroonie to a farm kid excited to get his first wheels. I had a lump in my throat watching him drive it away.

Always on the lookout for used equipment, when we heard that the local pole-bean farmers were switching to bush beans, we jumped at the chance to buy their used poles and wire. We sorted through piles of old bean stakes to find the strongest, straightest ones, and then Bill soaked them in foul-smelling, poisonous pentachlorophenol so they wouldn’t rot when he put them into the ground.

Not all our penny-pinching deals worked out. The spring after Nik was born, Bill bought an old Cat 22, a small Caterpillar bulldozer. The farmer guaranteed that it was almost ready to go. The cans of parts sitting on it, he assured us, would go together quickly. For the next two months, Bill and his dad spent many hours in that farmer’s field, forty miles from home, trying their best to put the thing together. Nik and I started out going along, but got bored sitting in the field watching them try to match the pieces. They got it running enough to load the little crawler on a trailer, along with miscellaneous cans of parts, and brought it to the vineyard. When, at long last, Bill proudly tried it out, he discovered it would turn only to the right. Neither he nor those he consulted ever did get it to work right. It was a long time before he was able to chuckle at his great money-saving scheme. We sold it for parts to someone equally ambitious about making an old Cat 22 run again.

Bill orchestrated our first vineyard planting in the spring of 1972. Bill’s family—aunt and uncle, cousins, and sister—came to help. When we were ready to put the plants in the ground, I drove the tractor, with Nik in the backpack, freeing Bill to carry the heavy bundles of dormant plants and pails of fertilizer. My job was to drive down the row, stop at the right spot, and drill a hole. The auger was mounted on the back of the tractor, so lining it up with the marker stake required prolonged twisting to look behind me. Nik had a great view of all the activity, but at seventeen months he was not happy being cooped up and his weight in the backpack made my job even more tiring. My back ached after the first hour.

August 1971. Bill Blosser (left) and me (right), with eight-month-old Nik on my shoulders, taking a break as we work on our new vineyard property. Bill is wearing his French vigneron beret.

I was rescued by Bill’s parents, Betty and John Blosser, who took their vacation time to drive up from Oakland and work in the vineyard for a week. Bill’s dad, an orthopedic surgeon, had a grin from ear to ear as he took my place. He loved driving the tractor. I never heard him complain about the twisting, or about back pain. Grandma Betty freed Nik from the backpack, played countless games of patty-cake, fed him, and made sure he napped. I gratefully accepted her help. From then on, until they finally moved to Portland, John and Betty came up every year, and we intentionally postponed major projects until they arrived.

We planted five acres that first year—one White Riesling, one Müller-Thurgau, one Chardonnay, and two Pinot Noir. When it was all over, we walked to the top of the hill and surveyed our new vineyard. I stood next to Bill, who had Nik on his shoulders, and looked out over the valley. Little sticks poked out of the reddish dirt in neat rows, and the freshly turned soil smelled clean and sweet. I was sweaty and hot, but a chill went up my spine. We had done it. We had literally put down roots.

WHEN PEOPLE ASKED, AND they always did, why and how we ever decided to start a vineyard, I was slow to answer because I really wasn’t sure how it happened. I said we were part of the back-to-the-land movement of the early 1970s. I said it was because we had more guts than brains. But I winced inside as I answered. Yes, starting a vineyard was unconventional, even outlandish, but neither of us were known for eccentric or bizarre behavior. We weren’t flower children or hippies, although our kids like to portray us that way. I picture us as a fresh-faced young couple, well educated, solidly middle class, and looking to be engaged in life with a purpose.

It is only with the perspective of time that I realize, looking at the bigger picture, that Bill Blosser and I were bit players in a drama far larger than we knew. We shared a small part of the incredible entrepreneurial energy that enveloped the world when we were young and ready for adventure.

The decade of the first plantings in Oregon vineyards, 1965–75, was one of political and social upheaval. When those of us who lived through it look back, what stands out are the Vietnam War, civil rights, and feminism that dominated the news. Race riots, antiwar protests, political assassinations, and bra burning were what we saw every time we turned on the TV news. What we didn’t see, but experience today in every facet of our lives, was what was happening behind the scenes in the business world, which was facing its own upheaval.

Radical thinking flourished in more than politics. This was a decade in which young entrepreneurs started looking at the world differently. Innovative companies that became household words got their start. Apple, Starbucks, Microsoft, Nike, and many more all began in that decade. Laptops, lattes, cell phones, high-end sneakers, word processing, gourmet home cooking—all these things that have become part of our lifestyle had their birth or blossomed in the decade between 1965 and 1975. It was an extraordinary time on all fronts and we are still reeling from the momentum created.

When Bill and I decided, in 1970, to start a vineyard—out-of-the-box thinking for two history majors—we were manifesting the innovative energy of the time. Like the Eraths, Letts, Adelsheims, Campbells, and Ponzis, who also dreamed of European wine grape vineyards, we were each following our own dream, not realizing we were part of a global phenomenon.

IN 1973, BILL AND I decided it was time to move out of our drafty rented farmhouse. We had lived the seven years of our married life in rented housing, never more than two years in the same place. I was pregnant with our second child, and we wanted a home of our own. We tried to buy a house nearby, but there weren’t many and none were for sale, so we had to build. A sloping corner of our vineyard, not good for grapes, would work for a house. Bigleaf maples and Douglas firs lined the west side, but we could look east, north, and south over the vineyard from the second floor.

The library’s books of house plans showed us boxy houses that seemed too conventional. Far more enticing were plans for vacation homes. These had imaginative shapes and angles that could be fun to live in. We chose an octagonal pole house. Neither of us had ever seen such a house, but it sounded interesting and we liked the idea of views from eight sides.

We hired a contractor from a nearby farming community, whose workers came from a local commune. We planned to have them only frame the house. We would do the rest ourselves and Bill took six months off to work on the house. He installed the whole electrical system and beamed with pride and relief when it passed inspection. To save money when he put up the drywall, he carefully cut and fit small pieces into the odd angles that an eight-sided house created. It took so much time that we decided to hire professionals to do the taping and ready it for painting.

The men we hired couldn’t believe that Bill had used so many tiny pieces and never stopped complaining about all the odd shapes they had to tape. I did much of the painting of the walls, propping myself against the ladder with my increasingly pregnant belly. We moved into our almost finished home just in time to celebrate Christmas. One month later, Alex was born.

We were thrilled to finally be in a home of our own, but it didn’t take long to discover that while an octagonal house looked good on paper, it was full of angles that made rational furniture arrangement almost impossible. None of the rooms had the square corners required to accommodate a cupboard, a TV, or a chair comfortably. Our main living area—living room, kitchen, dining area, master bedroom, and large deck—was on the second floor, overlooking the vineyard. The kids’ bedrooms were on the first floor. Below that, a daylight basement opened to the carport. We framed in space for a motorized dumbwaiter, with the idea that I wouldn’t have to carry groceries up two flights of stairs. But in the eighteen years we lived there, we never got around to building it.

As the second child, Alex had the advantage of my having been broken in by Nik. The youngest of four siblings, I never babysat or even paid much attention to children. I had no idea how to handle babies and was nervous that I would do something wrong and wouldn’t be a “good mother.”

In the rented farmhouse, I was generally alone all day, sometimes in total silence except for Nik’s wailing and the creaking of the rocker where I sat holding him, unable to stop the tears of helplessness flowing down my cheeks. Nik just kept crying. I changed his diaper and nursed him, held him, rocked him, and sang softly to him. What could it be? I reread my paperback copy of Dr. Spock’s book until it was falling apart.

Checking out the vineyard on a sunny day in early spring before the vines leafed out. Bill has four-month-old Alex in the backpack. Three-year-old Nik is in between me and Bill’s father, John Blosser.

It took me a long time to loosen up enough to enjoy my baby. Later I understood that his crying reflected my insecurity, and I carry a rueful tenderness in my heart for Nik who, as the first child, had to bear my learning curve of motherhood.

As I relaxed, I was surprised to discover how interesting, how much fun, and how individually distinctive my children were. My two boys were born three years apart: Nik, reserved and intellectual, with an unexpected silly streak; Alex, gregarious and unconventional, with an unexpected intellectual streak. They complemented each other, and the older they got, the more fun they had together. I found motherhood deeply satisfying, but never easy.

With the vineyard in its infancy and only a few acres planted, I had time to get involved in non-farm activities. I joined the McMinnville chapter of the American Association of University Women (AAUW) and through my new friends learned of a teaching opportunity at Linfield, a small liberal-arts college nearby in McMinnville. I grabbed the chance to indulge my interest in American history and do the work I had trained for. Hired as an adjunct professor, I taught for the next two years, first History of the American Revolution, and then History of Women in the United States. I had my own office in the History Department and worked so hard that I managed to turn teaching one class into a full-time job. The whole experience—planning and giving lectures, talking to students, being one of the faculty—was intellectually invigorating. The department chair gave me the freedom to formulate the syllabus for the courses, and I felt as if I were in graduate school taking a tutorial, except that I was also teaching it. The material was always fresh in my mind because I was absorbing it only days ahead of my class. Here was the stimulation I craved, and I stayed until it became a luxury I couldn’t afford. I was needed in the vineyard.

PEOPLE IN THE LOCAL farming community were curious about us since none of the farmers had experience with wine grapes. Our first contact with the community was Carrie and Les McDougall, a retired couple who lived in a pink, ranch-style house on the large lot adjoining the top corner of our property, the site of our first planting. Summer evenings we’d see them settled on folding lawn chairs in the driveway in front of their house and we’d join them when we finished work. The four of us talked about farming and looked out across our rows of grapevines, past a few big maple trees, and down onto the patchwork of farms on the valley floor. The distance made it seem peaceful, but farmers work long days, and the valley was full of activity.

“Golly, look at that,” Carrie would say, pointing to a tiny tractor moving slowly across a light green field in the distance. “I guess George is letting little Sam drive the tractor now.” Then Les would pipe up with “Look, over there,” and nod toward a spray of water moving back and forth across a faraway patch of dark green. “Phil’s irrigatin’ his beans again tonight. Must have a good contract this year with the cannery.” They’d point out a crew moving the water lines in a field of broccoli and tell us how a young man had been killed when the long piece of irrigation pipe he was moving crossed an electric line. From their lawn chair lookout, the McDougalls knew what was happening on every parcel of land.

Over the course of the 1970s, we bought several parcels of producing orchards from other neighbors, Ted and Verni Wirfs, who became our good friends as they slowly retired from farming. Ted showed his tractor skills helping us during grape harvest, hauling full totes of grapes from the steepest parts of the vineyard down to the winery. His expertise proved invaluable when it rained and the wet, slippery hillsides made maneuvering treacherous for less experienced drivers.

Verni knit Christmas stockings personalized with the names of each of our kids, provided us with one of her kittens when we wanted one, gave me starts from her unusual African violets, and showered us with a large box of her seasoned pretzel/cereal snack mix every Christmas.

Ted had an endless repertoire of stories about his years of farming, and he and Verni became a source of comfort and encouragement. After visiting with them, the problems we were struggling with always seemed more manageable. They lived from harvest to harvest with a curious combination of fatalism and optimism—making the best of whatever hand Mother Nature dealt and then welcoming each new year as a fresh start and another chance. As novices, we were grateful both for their advice and because they took us seriously. Many local farmers stopped short, looked at us sideways, and narrowed their eyes when we told them what we were doing. “You’re growing what? Why’re you doing that? Nobody’s done that around here.” Ted and Verni won our hearts and our loyalty by supporting us with their farming knowledge and their friendship.

I met many of the local farm wives when I accepted Verni’s invitation to join the Unity Ladies Club, which took its name from the local Unity School District, which had actually ceased to exist long before most of the club members were born. The ladies were older than I was, ranging in age from forty to nearly eighty. Each month a different member hosted and her dining room table, covered with a lacy crocheted tablecloth, would be laden with plates of freshly baked cookies, homemade pies or cakes, local walnuts and hazelnuts, and the obligatory dish of mints.

We chatted, sipped coffee or sweet punch out of flowery china teacups, and ate primly off the hostess’s best china. It was a Norman Rockwell painting and reminded me of the fun I had as a little girl having tea parties with my dolls and my mother, pretending I was grown up, and a lady. Here was the real thing. The ladies were very kind to me. When I was pregnant with Alex, they surprised me with the first (and only) baby shower I ever had.

Most of the women had lived their entire lives in the area and our conversation focused on their interests—mainly families, health problems, and crops. Meetings always had their share of “Did you hear about …?” Ruth Stoller, wife of one of the major turkey farmers, held the unofficial title of county historian, and entertained us with tales of local towns. In the early 1900s, stern-wheelers had brought people up the Yamhill River from Portland, giving Dayton, a little town near us, the name for its main drag, Ferry Street. Ruth showed us old pictures of passengers on one of the stern-wheelers, women in long dresses and bonnets and men wearing vests and straw hats.

The club leaders were the wives of the wealthiest and most successful farmers, the ones who raised turkeys, row crops, wheat, berries, or tree fruits. No one would have guessed, then, that within twenty years all the turkey farms, and most of the orchards and berry fields, would be gone, and nurseries and vineyards would be the area’s primary agricultural industries. By the turn of the twenty-first century, not a single turkey was being raised for sale in the county.

At the Unity Ladies Club in the 1970s, we weren’t looking to the future. We savored the moment, gossiping, exclaiming over the hostess’s culinary skills, drawing names for our “secret pals” each year, and exchanging homemade Christmas and birthday gifts. There was no reason to think our world would be any different in years to come. We could not have imagined how significantly the landscape would change over the next two decades.

AFTER BUYING TED AND Verni’s orchards, summer and fall turned into a continual harvest. We needed whatever income we could generate, so we kept the producing orchards going until we could afford to replace them with grapes. Life went like this: cherry harvest in late June, peaches July through August, prunes in late August, grapes in September and October, and walnuts in November.

The best part of our newly acquired orchards was that tree-ripened fruit introduced me to delicious new tastes. Before we owned the orchards, for example, I had only eaten canned Royal Anne cherries, which my mother would serve as a special dessert. How much better they were fresh and ripe off the tree. The whole family would go down after dinner and wander from tree to tree, plucking the biggest ones and popping them into our mouths for dessert. “Let’s go down and graze in the cherry orchard,” one of us would suggest and we’d all troop down the hill. I had also never eaten a tree-ripened peach. I couldn’t believe how much more flavorful it was than any I had bought in a store.

I felt it my duty not to let anything from our orchards go to waste. We were overloaded with fruit, even though I canned, froze, pickled, and made jam, preserves, and brandy. It became too much of a good thing. After about two years I admitted defeat. Worn out, it was a relief to finally accept that I simply could not use, or give away, all the fruit, and that I would have to let some drop to the ground.

The first orchards we took out were the peaches. They were the most difficult to grow and we didn’t have a secure market for them. Even after we had taken out all our trees, I liked to help Ted and Verni pick and sort their peaches for the fresh market. It was too big a job for the two of them, and they were so good to us that I was glad to help. Harvest started about five in the morning, while the peaches were still cold and firm and wouldn’t bruise from handling. We strapped on harnesses attached to large aluminum buckets so we had both hands free to pick. Unlike cherries or grapes, which could be harvested all at once, peaches had to be picked as they ripened, every few days. Everything about growing peaches was difficult, from fighting disease to propping up the trees laden with fruit, to the ordeal of picking. After experiencing a growing season, Bill and I concluded the only reason to go through all this was to enjoy the taste of a fully ripe peach. Besides being sweet and juicy, a tree-ripened peach has a perfume, intense and captivating. No other fruit we grew enveloped the senses so completely.

This was one place I couldn’t include the kids. Alex wanted badly to help me pick, but his hands were too small to get around the whole peach and twist it off without either bruising it or tearing the skin. Sometimes he would walk down to the peach orchard, about a quarter mile away, to find me when he got up. I think he knew we would be close to finishing and Verni would have something good for him to eat. We always finished the picking morning with freshly baked coffee cake. We sat as long as we could, until finally someone would say, “Well, guess it’s time to get back to work.” Alex and I would trudge back up the hill.

Cherry season had rituals of its own, from bringing in the bees in March to delivering the harvest to the processor in early July. There was nothing easy about any of it with the big old trees that comprised our orchard. Work began in the spring, as soon as we had a few dry days and could get in to work the soil. When the trees bloomed in March, we brought in beehives to pollinate the blossoms. We hoped for sunny days, but too often it was so cold the bees wouldn’t come out of their hives, and the beekeepers had to come to the orchard to feed them.

Full bloom in the cherry orchard enchanted me. Delicate white blossoms with a touch of pink covered the trees, giving them a gauzy, ethereal quality. Standing in the middle of the orchard surrounded by twenty-foot trees with frothy white, sweet smelling blossoms, listening to the steady hum of the bees doing their job, the cares of daily life receded.

Our aged cherry trees had thick trunks. Their branches hung low, making picking from the ground easier. The Latino crew we hired to harvest arrived early to cook breakfast before work. The smell of tortillas and onions greeted us as we came down to start the day. These men worked hard but still had time for animated conversation and jokes, and the sounds of their lively camaraderie filled the air. Each picker worked with a two-gallon aluminum bucket, a harness, and a wooden ladder. After the cherries were dumped into large wooden totes, we loaded them on our truck and took them to the brine plant at the end of the picking day.

Delivering handpicked cherries was a ritual of its own. After I got proficient driving our twenty-foot flatbed truck, I would make the trip with one of the kids—Alex always wanted to come—and our dog, Bagel, who was willing to go anywhere as long as she could ride. Thirty totes, three layers of ten totes each, put our truck at its maximum load. I tied the cargo down and drove slowly to avoid sudden stops.

During the peak of harvest, there would be a string of trucks at the cannery at the end of the day, waiting to be unloaded and sampled. Small pickups, straining under the weight of one tote, alternated with large flatbed trucks carrying many layers of totes. We sat in the long line, with the doors open to catch the breeze, and waited for our turn. The slow-moving line of trucks laden with fruit moved in a choreographed dance with the fast-wheeling forklifts unloading totes.

Payment depended on how well our cherries fared in the grading, which took place while we watched. The forklift brought several totes over to the grader, who put handfuls from random totes into a small bucket, and then examined each cherry. I held my breath with every one. Perfect cherries with stems went to the drinks-cocktail market, fetched the highest price, and went into pile number one. The second pile was perfect cherries without stems, suitable for the baking market. The third pile was rejects—cherries that were split or showed any rot—for which there was no compensation. My heart sank at every reject. After sorting, the grader weighed each pile, calculated its percentage of our sample, and applied that percentage to our whole load. Growers tried to top-dress their totes, putting the best cherries on top, but the graders knew to dig down to get the samples. During cherry harvest, the cannery stayed open to receive cherries long past dark, often until midnight.

We farmed the cherries longer than the other fruits. In 1987, with relief but also nostalgia, we took out the last cherry trees. Finally, we could give our entire focus to our vineyards. But alas, there was no more grazing in the cherry orchard after dinner.

BILL AND I WERE on a steep learning curve. From the time we cleared our first piece of land in 1971 to building the winery in 1977, everything we did—starting a family, farming orchards, building a house, planting a vineyard, starting the winery—was a new experience. As soon as we put the vines into the ground, we were on an express train, with nature at the wheel. Everything needed our attention at the same time. Life was so full, and moving so fast, that we didn’t have time to reflect on the wisdom of our undertaking. We fell into bed and slept soundly every night, waking only when a baby cried.

My father’s business success in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, enabled him to indulge his love of wine and become our partner in 1974. He invested as soon as he was convinced we were serious about our project. He invested only a bit of cash, but he encouraged us to expand by guaranteeing loans for us at the Milwaukee bank that handled his business. His help was crucial, because local banks thought we were just as crazy as everyone else did and refused to lend money to such a risky project. With my father’s help, we were able to buy adjoining parcels of land as they came up for sale. We benefited from having our vineyards contiguous. On the other hand, financing our operation so completely through debt left us undercapitalized and financially vulnerable, a condition that plagued us for years.

Daddy envisioned a family winery where we could ferment the grapes we grew and craft them into fine wines on our own land and by our own hand. Bill and I, barely able to keep the vineyards and orchards under control, were daunted at the thought of adding a winery. But spurred on by my father, Bill started researching startup costs and building materials and hired a marketing consultant to help estimate income and costs for the first ten years. He hired a winery design consultant to help lay out the winery and select equipment. As Daddy’s enthusiasm grew, he talked my three older brothers into investing.

The next step, getting permission to site a winery on our property, became an unexpected hurdle. The land use regulations we both strongly favored became our stumbling block. Because of his training, Bill was a firm believer in land use planning and didn’t mind having to go to the county planning commission for approval to construct a winery on farm property. Oregon had just buttressed its land use laws, the legacy of Governor Tom McCall, one of the state’s most colorful and well-loved politicians. McCall took a forceful stand on controlling growth that gained national attention. In a CBS interview in 1971, he quipped, “Come visit us again and again. This is a state of excitement. But for heaven’s sake, don’t come here to live.”

When Governor McCall pushed the Oregon legislature to pass a state land use bill in 1973, mandating that each county decide how the land within its boundaries should be used—what should be designated agricultural, residential, commercial, or industrial—Bill put his planning degree to use by getting involved. His goal was to convince county planners to designate the hillsides where we had vineyards as agricultural, rather than as residential “view property,” which was the route they were headed. Hillside soils, with their lower fertility and excellent drainage, suited wine grapes, and gave the vines natural frost protection because they were a few degrees warmer than the valley floor. The small group of winegrowers worked together to convince the county that vineyards were the wave of the future and the hillsides should be designated agricultural.

The designation of hillsides as agricultural, with twenty- and forty-acre minimums, became vital protection for the wine industry. The efforts of the early winegrowers meant the hillsides in Yamhill County would become dotted with vineyards instead of trailer parks or subdivisions. In neighboring counties, where the growers were less active in shaping the law, hillside housing developments encroached on farms and vineyards as the population of metropolitan Portland expanded.

Oregon entered the twenty-first century as the only state in the nation with a comprehensive land use program. Governor McCall’s land use initiative, Senate Bill 100, passed at an extraordinary time in Oregon’s history, when visionary and strategic politicians from both political parties found a way to work together, thinking of future generations and the betterment of the state. Its implementation coincided neatly with the development of Oregon’s new wine industry.

As we moved ahead with our winery plans and applied for the land use permit, we saw a side of Yamhill County that we had known was there but hadn’t paid much attention to—teetotaling religious fundamentalism. Without our knowledge, a few fervent winery opponents carried around petitions requesting that the county deny our permit. While the petition said nothing about God, religion, or the evils of alcohol, we found out that the leaders of the petition drive were either Mormons or members of the Church of God, a fundamentalist Christian denomination. Both groups were vigorously anti-alcohol. As long as we only farmed, we were accepted into the community. But the winery we were proposing represented something new and threatening. We suddenly found ourselves thrust into the role of outsiders.

Our neighbors’ imaginations ran wild thinking about the terrible possibilities. “Do you want drunks from the winery roaming the hills?” the petition carriers would ask their neighbors. They mentioned rape. “Our homes and women wouldn’t be safe.” Petitioners asked their neighbors to imagine the flashing neon signs that would undoubtedly be on top of our winery to attract people off the highway a quarter mile away. In sum, a winery would be a blight on the neighborhood, threaten the well-being of their families, and endanger their quality of life. If I had believed all the things they said would happen, I would have been against us too. The petition recorded fifty-three signatures. I was saddened to see the signatures of some of my Unity Club friends. No one had talked to me about their concerns—they had just signed.

Adding fuel to the religious opposition was political opposition roused by Bill’s work on the county land use plan. Saving hillsides for agriculture might have been good long-range planning, but it infuriated farmers who had wanted to divide their land into smaller parcels or build more than one house on it. After working on the county plan, Bill was appointed to the Yamhill County Planning Commission, whose task was to uphold the new plan. He recused himself when we applied for our winery permit. People who had been denied their petitions saw a chance for revenge. One opponent stated flatly, “Blosser kept me from getting my request; I’m sure as hell going to keep him from getting his.”

The hearing before the Yamhill County Planning Commission, February 17, 1977, took place in the basement of the Yamhill County courthouse. The low-ceilinged hearing room was packed when we arrived. I wondered what had brought out all these people and was shocked when I found out they were there for us. Or rather, against us. We were blindsided. The fierce looks on people’s faces made it clear that Bill and I were the enemy and it was their mission to defeat us. Our permit request was the second item on the agenda. The commissioners never got to the third item; our hearing took up the rest of the evening.

The anti-winery faction had turned out in force, bringing an attorney, people to testify, and their petition full of signatures. Many of the complaints had nothing to do with the proposed winery but spoke to vineyard issues—the use of noisy air cannons to scare away birds, fear of the migrant workers employed during harvest. “Technical” reasons for opposition were that a winery would lower the water table by using too much water, cause pollution, lower property values, create traffic jams, generate offensive odors with fruit waste, promote drunkenness, be a visual blight in the neighborhood, and be incompatible with the existing development in the area.

Bill quietly and methodically presented our case and painstakingly rebutted the opposing testimony, point by point. He had put in a full day of work in Portland and barely had time to grab dinner. Alone and vulnerable in the face of such intense opposition, I could see him struggling to stay calm and not rise to the emotional pitch of his opponents. Surrounded by a sea of angry people, wishing I were anywhere else, I listened to people around me condemning our project. I could feel my shoulders hunching up around my ears.

A tension-relieving moment came when Howard Timmons, a retired farmer who owned a large parcel at the top of our hill, stood up to testify against the noise from our bird-scaring air cannon. He was feisty and agitated about how bothersome that was. When he finished, Bill asked him to clarify one of the allegations. Silence. The audience looked expectantly at Howard until his wife, Hazel, finally interceded to explain that he hadn’t heard the question; he was almost deaf. People couldn’t help laughing, even though Howard had most certainly damaged their case. The absurdity of Howard complaining about the air cannon he couldn’t hear epitomized, for us, the whole anti-winery campaign.

After three hours of testimony, the planning commissioners, apparently perplexed by the strength of the opposition, questioned their staff, which had recommended approval. After making sure the opponents’ arguments were unsubstantiated, they voted unanimously to approve the project and send it on to the Board of Commissioners for approval.

When we got home, Bill was exhausted and I was still so upset that I rolled Bill’s exercise bike into the living room, hopped on and pedaled as hard as I could, venting the anger I had controlled at the hearing. The personal attack and questions about our morality had hit a nerve. The testimony on religious grounds such as, “I am against the winery because of my Christian family values” implied that because we wanted to start a winery we were immoral. Their condescension and sanctimony infuriated me. Their behavior struck me as very un-Christian. This was my first encounter with outspoken prejudice in the name of God, and it was a rude awakening.

At the commissioners’ hearing two weeks later, the anti-winery faction was back in force. This was their chance to appeal to the three men who had been elected to the Yamhill County Board of Commissioners and had the final say over policy issues. The commissioners listened carefully to their constituents and did not automatically adopt the recommendations of the planning commission. We knew our opponents had a good shot with their appeal. Each person who testified against us presented a picture or map showing how close they lived to the proposed winery and pointed out the dangers they faced—waste and water runoff flowing onto their property, increased traffic driving by their residences, a sinful business corrupting their family life.

But this time we came armed, bringing neighbors and other winery and vineyard people to speak on our behalf. I had eighteen signatures on a petition requesting that any decision by the Board of Commissioners be based on facts, not fears. Most people had signed our opponents’ petition simply because either a neighbor had asked or they were scared by the scenarios the petitioners had described. The small core of people who set out to defeat the winery proposal had stirred up a lot of commotion and I realized I needed to do damage control.

Immediately after the planning commission hearing, while Bill was at work in Portland, I had gone to visit the neighbors to explain what we wanted to do. After my visit, most wanted to stay out of the fight entirely, realizing that our winery would not cause the problems they had been led to believe. By presenting a map showing the locations of neighbors who were opposed, in favor, and neutral, Bill was able to demonstrate that more homeowners in our immediate area were in favor of our application than were opposed. Bill’s quiet dismantling of the opposing testimony contrasted sharply with the emotional, often illogical testimony of those against the winery.

The commissioners, probably baffled by all the turmoil over what seemed a straightforward issue, postponed their decision for two weeks. Finally, they came out in favor of our application for a land use permit. We celebrated, but the fight was not quite over. The hard core of the opposition appealed the county’s decision to the courts, throwing us into a quandary. We had been waiting for resolution before starting construction. If we waited until the appeal wended its way through the courts, we would not have the winery ready for the 1977 crush. We were pretty sure the courts would uphold the county’s decision, but what if they didn’t? We decided to take the risk. When a court decision in our favor finally put an end to the long, emotional battle, we could move full steam ahead.

Our experience paved the way for future wineries; the county made the establishment of a winery on land with a minimum number of vineyard acres an outright permitted use, on the assumption that a winery facility was needed to process the fruit. Later wineries did not have to face the same kind of opposition that we did.

Once the winery was built and the neighbors saw their fears were groundless, they took pride in it. Within fifteen years, the wine industry had gained sufficient status that land that had cost eight hundred dollars an acre when we started was selling for as much as fifteen thousand dollars an acre. Soon after that, it more than doubled and is still rising. The same people who fought us started actively promoting their properties as vineyard land, with premium price tags. Years later, in exquisite irony, the poorly producing wheat fields Howard Timmons fought to protect from the wine business sold for a bundle to become high-value vineyards.

On October 10, 1977, the day finally came when our first block of grapes was ready to pick and we could start the winery’s first vintage. Our twenty-person crew started at seven in the morning and didn’t stop to eat until they finished, working as if they’d each had a shot of adrenaline. Wielding curved knives with wooden handles and leather wrist straps, they grasped the grape clusters and cut the stems with swift, short strokes.

In the quiet early morning, as the picking began, the only sound was the clusters thudding into empty buckets. As the pickers got into a rhythm, the noise level rose. Soon the air was alive with the sounds of pickers running and shouting to each other, grapes sloshing into the totes, tractors chugging back and forth. Each picker had two plastic five-gallon pails, and each time he emptied them into the wooden tote at the end of the row the contractor gave him a ticket to turn in for pay. The pickers ran, even with full pails, shouting their numbers to the contractor, stuffing their tickets into their pants, hustling back to pick. The contractor barked instructions and warnings (in Spanish): “Don’t pick so many leaves! Fill your buckets to the top! Pick the whole vine! You’re leaving too many clusters on the back side!” The pickers were mostly men, but some women came, and a few brought children who hung around with their parents. Pickers sometimes missed whole vines or skipped clusters that were hard to reach. I didn’t want to waste a single grape of our first vintage and walked up and down the rows with a bucket picking the fruit they had overlooked.

We tried to sort the grapes as they went into the totes, taking out the leaves and any clusters that looked underripe or diseased. Most of the time I stood at the totes with the contractor to monitor the picking. Ted Wirfs brought his tractor to help our vineyard foreman, Wayne, lay out the totes in the morning, and then ferry them to the winery as they were filled. Nik and Alex, then six and three, were in on the excitement; I had hired a babysitter to be with them so they could participate in our first vintage. Clad in rubber boots, blue jean jackets, and baseball caps, they watched big-eyed.

One by one, over the course of the month, the other blocks of grapes ripened too. The dark purple, small-clustered Pinot Noir grapes went directly from the stemmer-crusher into large, open-topped wooden vats to ferment. Three times a day, Bob McRitchie, our wine-maker, and Bill took turns standing on a wooden plank laid across the top of the open fermenter, to punch down the cap of grape skins that had risen to the top. To do this they had created a tool—an inverted dog dish attached to a long piece of PVC pipe.

When fermentation was complete, they pumped the Pinot Noir back into the press and pressed the juice off the skins. Then the young wine went into small French oak barrels for aging.

We finished harvesting our Chardonnay and Riesling, the last of the grapes, on October 22. By then we were starting the picking day bundled up against the cold. The fall rains were threatening to settle in for the duration. But the grapes for our first vintage were safely in.

Deciding what to call our new winery turned out to be surprising difficult. I was certain there was a perfect name that would call out to customers in wine shops and make them want to grab our bottles off the shelf. We just had to will that name into our consciousness. We thought of names that highlighted local towns, the hillsides, the vines, the river, the creeks. Nothing had the right magic. I concluded we simply weren’t creative enough. The marketing consultant Bill had hired consoled us. This winery was our baby, he said. Giving it our family names would let potential customers know that real people were involved. “Remember that slogan for lacy women’s bras? ‘Behind every Olga, there’s an Olga’? Put your names on the line—both your names, since you’re equal partners.”

So Sokol Blosser it was. After all, we told ourselves, Orville Redenbacher, the popcorn king, and Smucker’s, the jam people, had used their odd family names. That didn’t keep them from being successful. We could do it too. Bill’s friends teased him about putting my name first, but it was the right marketing decision. We were going to use the initials SB as part of our winery logo.

Once we had our name, we engaged a Portland graphic artist, Clyde Van Cleave, whose work we liked, to design a wine label for us, which we used, with only color modifications, for the next twenty years. The label was about three inches by three inches, with a rounded top that arched over the SB logo. Later, the black and brown lettering on textured beige paper seemed drab, but at the time we thought it fresh and exciting.

Located on a busy state highway, we had great visitor potential. We decided to build a tasting room, although no other Oregon winery had more than a converted garage for the public to visit. Our marketing consultant advised us that a tasting room would be an indispensable public-relations tool as well as a retail sales opportunity. It turned out to be one of the best pieces of advice we received.

A mutual friend introduced us to John Storrs, a Portland architect noted for his imagination and ability to design for the natural setting. John had designed several Oregon landmarks, the best known of which was Salishan Lodge, a resort on the coast that had become an instant mid-twentieth-century architectural classic. Tall, boisterous, and charismatic, John always dominated the space he was in. “Blueprints are just a formality,” he declared. He designed as he built. We enjoyed him and watched as he wandered around changing things after construction had begun—an opening here, a window there. He drove the builders crazy with his unconventional style. They grew to dread his visits, as they knew he would find something he wanted redone. But the result was better for it.

Our first wine label, with the SB logo and our winery name front and center. An exciting moment to see it on a bottle of our first Pinot Noir vintage.

In the summer of 1978, Sokol Blosser opened the first Oregon tasting room designed specifically for that purpose. The gray stucco building hugged the knoll and coordinated well with the gray concrete winery building. The existing large oak and maple trees and landscaping with native plants provided color and contrast. On a clear day, Mount Hood loomed majestically, perfectly centered in a large east-facing window. Besides a tasting area, we had a small kitchen, a tiny one-person office, and the requisite two bathrooms. The back door opened to a breezeway that connected the tasting room with the winery.

I ran the tasting room on weekends for the first few years. Behind me on the wall is a framed needlepoint my mother did for me. Underneath that are our first medals from wine competitions.

There was another door in the main tasting area, six feet off the ground, anticipating the big deck we wanted but couldn’t afford. That door remained nailed shut for the next twenty years until, in the late 1990s, the deck was finally added.

Once we had the tasting room, the challenge was to get people to visit on weekends, when we were open. Wine touring in Oregon was not yet in vogue. We sent out mailers to friends and friends-of-friends and threw a big party. Slowly the word spread. I spent weekends behind the bar welcoming people and pouring free tastes that we hoped would lead to sales. It was months before we could hire any help and years before we could be open more than weekends. The kids were always with us. During cherry season the first year, seven-year-old Nik demonstrated his entrepreneurial skills by showing up with fresh cherries from our orchard to sell to customers. Taking his cue from the way we worked the tasting room, he offered free tastes. He never failed to sell out.

THE EARLY WINEGROWERS IN the Willamette Valley were a close-knit group. We shared information and cooperated to chart a course for the new wine industry. This willingness to work together for the good of the whole became a distinguishing feature of Oregon winegrowers from the start. We understood our actions would shape the future and thought hard about what we wanted the Oregon wine industry to look like.

The whole industry, which was ten to twelve people in the early years, met regularly in each other’s living rooms, sitting around on mismatched thrift store furniture, a decor which we called “Contemporary St. Vincent de Paul.” First, we shared news of hot deals on equipment or supplies. Then, after passing along the address of a farmer who had stakes, wire, or used equipment for sale, we talked about what legislation we might need to protect our fledgling industry. Not every session ended in consensus, but we kept meeting until we reached it.

One issue with lasting effect was tightening Oregon’s labeling regulations. At the time, federal wine-labeling regulations were lax, shaped by the practices of industrial producers in California and New York. A winery could legally give a wine a varietal label, such as Pinot Noir or Chardonnay, when as little as 51 percent of the grapes in the bottle actually came from that variety. We didn’t want wineries compromising our reputations by labeling a wine “Pinot Noir” when 49 percent of it was made with less expensive grapes. Using cheap table grapes like Thompson Seedless would have been legal. We wanted the world to know that if the wine came from Oregon, virtually all the grapes would be the variety printed on the label.

Dave Adelsheim wrote up the regulations we had all agreed to and presented them to the Oregon Liquor Control Commission (OLCC), the state regulatory agency. The OLCC was not eager to have stricter laws than those required by the federal government, but with the whole Oregon wine industry behind the changes, it agreed. By the late 1970s, when our new regulations went into effect, any Oregon wine with a varietal label had to contain at least 90 percent of that variety. We made an exception for Cabernet Sauvignon, requiring only 75 percent, because in the grape’s French home, Bordeaux, similar varieties were often blended into the wine. Oregon’s stringent new labeling requirements influenced the federal rules, but not for another ten years. At that point federal regulations raised the requirement for varietals from 51 to 75 percent, better for consumers, but still far below Oregon’s standard. California and Washington winegrowers accepted the federal regulations. Only Oregon had tighter restrictions.

Another piece of the new regulations concerned generic wine names. As growers of Pinot Noir, the grape of Burgundy, we were outraged that some large California wineries would put a blend of cheap red grapes together and call it “Burgundy,” trading on the prestige of Burgundian wines and intimating that their product would taste as if it had been made of Pinot Noir grapes. So we devised a regulation that said Oregon wines could not be named for a geographic region unless all the grapes actually came from that place. This precluded labeling wines Burgundy, Chianti, Chablis, or Champagne—all names of wine regions in Italy or France. In reaching consensus on labeling regulations and persuading the government to implement them, the Oregon winegrowers demonstrated a level of cooperation and commitment rarely found in an industry whose members are ultimately in competition.

IN THE EARLY MONTHS of 1979, when Nik was eight and Alex was five, Bill and I suddenly realized that our boys were growing up fast. Bill commented he missed having a baby around and I surprised myself by admitting I did too. Impulsively, I stopped taking birth control pills and was soon pregnant. The boys were excited, since they were old enough to have proprietary interest in a new brother or sister. We had planned to tell Bill’s parents at a family gathering, but Alex, full of importance with his new knowledge, blurted out, “Mama’s going to have a baby!” to Grandma Betty and Grandpa John before we even got through the front door.

Because I would be thirty-five when the baby arrived, the age after which pregnancy was considered riskier, my doctor recommended that I undergo a new procedure, amniocentesis, to check the health of the fetus. I had the procedure, then waited six weeks, which seemed an eternity, for the report. After reassuring me about the baby’s health, the nurse who called asked if I wanted to know the baby’s sex. When she told me I was going to have a girl, I burst out crying. I hadn’t realized until then how much I had wanted a daughter.

Our baby girl arrived in December 1979. Alison was so much younger than her brothers, I worried they would boss her around—a predicament I knew well, growing up with three older brothers. But Alison seemed born to take charge and quickly proved she could hold her own. One night, when Bill and I had prevailed on the boys to babysit, we returned home to find four-year-old Alison clutching a large wooden spoon while playing Lego with her brothers. We knew something was up.

It turned out that after we had left, the boys had gone off to play, leaving Alison alone. She didn’t like being ignored and decided she wasn’t getting the babysitting to which she was entitled. So she got a wooden spoon from the kitchen and ran after them with it until they paid attention to her. They were more amused than scared, but they gave in and played with her. The episode firmly established Alison’s reputation for not taking any guff, and Alison threatening her older brothers with a wooden spoon became a family joke.

We had started the decade with a new baby, a wild business idea, and a bare piece of land. By the end of 1979, we had three children, a mature vineyard, and a fledgling winery. What a decade it had been.

Mac & Cheese

In the 1970s, Bill was commuting to Portland for work and got home just in time for dinner, so I had all the cooking duties. One of our staples, which the kids loved, was homemade macaroni and cheese. It’s still a comfort food for them and their families today. When I told cookbook author Marie Simmons how I put the dish together in those early days of the vineyard—a quick one-pan recipe that didn’t require a separate sauce—she helped me re-create this recipe. Sokol Blosser Pinot Gris would be a great pairing.

Makes 6 to 8 servings

1 teaspoon coarse sea salt, plus salt for cooking the pasta

2 cups elbow macaroni

2 tablespoons butter

2 tablespoons all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon dry mustard

3 cups whole or two-percent fat milk

2 cups shredded Monterey Jack cheese

2 cups shredded sharp cheddar cheese

Bring a large saucepan three-fourths full of salted water to a rolling boil over high heat. When the water is boiling, stir in the macaroni and cook until it’s almost tender (taste a piece), 8 to 10 minutes; the macaroni will continue to cook in the sauce. Drain the pasta through a colander and return it to the hot pan.

Immediately add the butter, flour, mustard, 1 teaspoon salt, and the milk to the pan and place over medium-high heat until the liquid begins to boil. Reduce the heat to medium-low and cook, stirring constantly, until the sauce is smooth and thick, about 5 minutes. Add the cheeses and stir until well blended.

Remove the mac & cheese from the heat and serve right from the pan. Or, for a casserole, pour the macaroni and cheese mixture into a buttered shallow baking dish and bake in a 350°F oven until the top is golden, about 20 minutes.