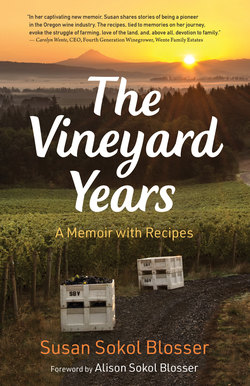

Читать книгу The Vineyard Years - Susan Sokol Blosser - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

A Sense of Place

My father, who loved to say that the best fertilizer is the farmer’s footsteps on the land, had been urging Bill to devote his full attention to the vineyard and winery. In early 1980, shortly after Alison was born, we decided the winery could afford to pay its president, so Bill quit his job in Portland to be the full-time winery president. Every morning after breakfast, he walked to work, through the vineyard, down the hill to the winery. I watched him disappear among the vines, wearing jeans, and vineyard boots, and carrying his briefcase—the only vestige of his city job. His suit and tie collection hung in the back of the closet, reserved for sales trips and meetings with the banker. He no longer spent two hours commuting, and it felt as if he were closer, but really it meant he could spend more time working.

Having Bill at the winery on a daily basis changed our dynamics. I had been running the tasting room pretty much on my own. With Bill there I was less autonomous, and I didn’t want him to be my boss. He understood and we looked for an arena that could be mine. Why not running the vineyard? I kept the books and wrote the checks; I could learn to do the physical work, too. We decided I could shift my focus.

I knew this would be an adventure since my only claim to farm life is that when I was born, in 1944, my parents, Phyllis and Gus Sokol, lived at Melody Farm, in Waukesha, Wisconsin. In 1942, to counter the austerity measures of World War II, they gave up the city life they had always known and moved with their three sons to the country, where they could grow their own food. Their farm life, with its classic whitewashed brick farmhouse, orchards, and barns, bordered by a split rail fence, lasted only seven years, but it loomed large in our family lore.

Stories of my mother driving a horse and buggy to the local store during wartime gas rationing and my father keeping chickens, pigs, and horses kept the memory alive, but my personal knowledge of farm life was nil. By the time I was four, we had moved back to the city. I grew up as a middle-class urbanite. My early memories include helping my father choose which patterned silk tie to wear with his suit for his workday; hearing my parents talk about the theater and concerts they attended; falling asleep listening to the adventures of Gene Autry on the big radio next to my bed; and smelling my mother’s perfume and feeling the tickle of her fur coat on my cheek as she leaned down to kiss me after coming home from an evening out. I can’t imagine either of them harnessing a horse or mucking out a chicken coop.

But managing our orchards and grapes put me in the vineyards every day for much of the 1980s. Wayne Cook, the young man we had hired as our foreman, patiently trained me on all the equipment. Although I was his boss and twelve years his senior, he took time to show me things—little things, like where to find the grease fittings on each piece of equipment and how to refill the grease gun from the bulk grease barrel, and big things, like how to use the forklift to load totes of grapes onto our big flatbed truck, tie down the load, and start moving. I started with almost zero knowledge, so was grateful that he was never arrogant or overbearing.

Little by little, I learned what needed to be done, how to get the equipment ready, and do the work myself. I gathered a store of information about things that I had never before even wondered about. I’d never had an urge to know how to attach a piece of heavy equipment to the back of a tractor, but now I learned how to maneuver the tractor into position so I could do it without heavy lifting. I’d never imagined driving a twenty-foot flatbed truck, but now I learned how far into the intersection to go before starting to turn a corner. I absorbed the rhythm of the vineyard year and what needed to be done each season in the orchards and vineyards—pruning, fertilizing, spraying, canopy management, crop estimates, harvest procedures. I took a farm management class to get a better understanding of the business side.

I threw myself into my vineyard work, wishing I could inhale all the new information and relishing my new skills. Crouching to lubricate a piece of farm equipment, my overalls covered with dust and my hands and nails stained dark brown from the grease, I’d suddenly wonder what my high school friends would think if they could see me now. My parents proudly displayed a photo of me as a debutante in which I looked out from the sterling silver frame, elegant in my white strapless gown and elbow-length kid gloves, my hair in a French twist. It was about as far from my vineyard life as I could imagine. The image made me smile, not only at the contrast but also at the unexpected turns my life had taken. I would not have changed places with anyone.

Something happened to me when I got out into the vineyard. It both freed my spirit and tied me to the land. Being responsible for the farm focused my attention and stimulated my mind, but being in the orchards and among the vines penetrated right to my gut, giving me a sense of oneness with the land and a fulfillment I had never imagined. I could have lived my whole life in a city and never discovered those feelings. Until then, I’d participated with more fervor than I felt. After taking over the vineyards, I finally began to take emotional ownership of the project that had been swirling around me and dominating my life for a decade. My passion for our venture grew steadily from then on, until finally it surpassed Bill’s.

Even now, I can close my eyes and imagine myself walking down a row of vines early on a summer morning. My feet are wet from the dew soaking through my boots. The air is fresh, cool on my skin, and very still. The vines are bright green and lush with new growth. The sun, just touching the vines, will soon be intense. If I am lucky I will spot a nest, probably from one of the bright yellow goldfinches, hidden in the vine canopy.

Or, I imagine it is the end of a summer day, when the sun casts long shadows in the vineyard and all the colors look deeper and richer. Above me, the swallows swoop and swirl, snatching bugs out of the air. A small breeze makes the growing tips of the vines wave gently. I can feel the heat of the day fade as the sun starts to set and a hush settles over the land.

In October, during harvest, the vineyard starts the day shrouded in mist. Viewed from the vineyard’s highest point, only the tops of the tallest Douglas firs poke through, reminding me of a Japanese landscape painting. In the foggy wetness the pickers start, breaking the dew-covered spiderwebs that stretch across the rows. By noon, the day will be gloriously sunny, with the crispness in the air that is autumn.

In winter I see the skeleton of the vineyard, the trunks and canes of the vines stark without their leafy cover. Its austerity is striking, whether cloud-shrouded and bleak with rain, or snow-covered and glaringly bright. The vines sleep a long time, from December to April. By then I am eager for the vineyard to come alive. My heart sings as the swollen buds start to unfurl into tender green leaves, pink-hued around the edges. Baby clusters emerge with tendrils like tiny curls. The birds start nesting again. The air feels soft. What will this season bring? It could be a great year. A farmer’s hope is always highest in the spring.

Each new vineyard year starts in the winter, when the vines are dormant, with our crew pruning away most of the previous year’s growth. It is done in January, February, and March, when the weather is miserable—pouring rain, cold and windy, or just gray. Layers of long underwear and flannel underneath yellow rain pants and slickers, rubber boots and fingerless wool gloves completed the well-dressed pruner’s look.

During my years in the vineyard, pruning season was one of the most sociable times, despite the fact that it took place during the worst weather of the year. In addition to our own small crew, I hired three or four extra people each winter to help.

On rainy days, we would prune with our hoods up and our heads down, each in our own row, with only the sound of the loppers breaking the silence. But when the rain stopped, we would throw back our hoods and the conversation and singing would start.

At noon we would sit in the vineyard office—the basement of our house—while we dried off and warmed up, the ambrosia of wet rain gear, tuna sandwiches, corn chips, and fresh oranges permeating our conversation. Someone had given me a book called Totally Tasteless Jokes and we took turns reading it. The jokes were pathetic and we mostly moaned at them, but then one would strike us as hilariously funny and the laughter felt good. Occasionally—just often enough to keep us from rain-induced depression—the sun came out and the whole world looked different: blue sky, bright sunshine, and snow-covered Mount Hood looming over the vineyard, its majestic peak alternately tinged with pink, gold, or blue. What a glorious feeling to be working outside! How lucky we were to be working in the vineyard! We strode up the rows more boldly and sang louder on those days.

SOON AFTER I STARTED in the vineyard, we witnessed Mother Nature’s stunning power. On the morning of May 18, 1980, Mount Saint Helens erupted with a force that sent a plume of ash fifteen miles into the air and created the largest landslide in recorded history. A wall of logs and mud flowed down leveling everything in its path—forests, homes, roads, bridges, wildlife—and leaving miles of desolation blanketed in gray ash.

It was a Sunday and the five of us had been to a birthday brunch for Bill at his parents’ home in Tigard, about seventy-five miles from Mount Saint Helens. Shortly after leaving their home, we saw the effects of the eruption. We sat in the car at the top of a hill and watched in awe as the mountain sent up a huge, roiling cloud of ash. The actual explosion surprised everyone, although the possibility of an eruption had been in the news for weeks. We had watched endless television interviews with people forced to evacuate their homes. Those who refused to leave vanished without a trace. Ash drifted far beyond the area desolated by the eruption. In Portland, the gray dust clung to grass and shrubs for months. A thin layer of ash even landed on our vineyard, but it barely covered our hillside and didn’t cause any harm. We drove to Hillsboro, northwest of us, where the ash was almost an inch deep, and Nik and Alex gathered it in buckets to keep as souvenirs. Then they got the bright idea of putting it in little bags to sell to tasting-room visitors. They sold out so I never had to deal with buckets of leftover volcanic ash. Local farmers plowed in the ash, the crops suffered no harm, and the 1980 eruption of Mount Saint Helens took its place in local lore next to the Columbus Day Storm of 1962.

We did many experiments in the vineyard and the one for which I had the highest hopes turned out to be our biggest failure. We got the idea of using geese in the vineyard when we heard they were used to weed the fields at mint farms—they ate the weeds and left the mint. I envisioned a pastoral scene with fat, happy geese wandering around the vineyard, feasting on weeds and leaving the vines to grow healthy and lush. Here was an idea that had everything going for it. It was more environmentally friendly than spraying herbicide or running equipment to mow or till, and it would save time and money. We chose a block of vines that we could fence relatively easily—three acres of Riesling adjacent to our house. We could watch the geese from our deck.

There were some immediate obstacles. We needed to fence, but we also needed to get a tractor up and down the rows to spray for mildew and botrytis (rot). We met this challenge with a makeshift chicken wire fence that had to be removed when we needed to spray, which was every ten to fourteen days all summer. But we figured all this extra time and energy was a small price to pay for such a great idea.

Two dozen white Chinese goslings arrived at our house in March. I had never had any farm animals and couldn’t wait. When we opened the box, forty-eight tiny bright eyes looked up and gave us little goose smiles, accompanied by considerable twittering. We bonded immediately. They were so little that we put them in a small pen until they got bigger and we got the fencing in place. They came waddling, honking eagerly, whenever they saw or heard us. We chuckled at their antics.

In April, when the vines had not fully leafed out but the grass and weeds were growing fast and at their tender and tasty best, we embarked on our great experiment. As far as we knew, no other vineyard in Oregon had even thought of trying this. We put the geese in among the vines, in a section that has been known since as the Goosepen Block. The young geese loved their new freedom and wandered around giving all the various plants the taste test. I expected they would develop a taste for the leafy weeds. The vines would be too high for them to reach, anyway.

Our plan started to fall apart right away. The geese just wanted to be near us. When we went out onto the deck to see how they were doing, they’d come running over and line up along the fence, honking at us. When we weren’t outside, they would sit quietly at the fence and wait for us to reappear. I tried going into the vineyard and showing them the far reaches of the block. They dutifully allowed me to herd them, and then they went back to their positions along the fence line facing our house. We thought maybe the geese would cover more of the block after they had eaten all the weeds in the section near the house. It never happened. They spent the rest of their lives trying to be near us, while the weeds grew freely. We knew it was time to act when the young geese got big enough to reach the grapes hanging on the vines.

In the end, we chose one pair to keep, and the rest of the geese ended up in our freezer. I cooked one, but we couldn’t bear to eat it. They stayed in the freezer for years. I was simply unable to bring myself to deal with them. It wasn’t until we moved, and I had to empty the freezer, that I finally closed the chapter on the geese—except, that is, for the two goose-down pillows that Bill had given me for Christmas. For many years we laid our heads on the fluffy remains of our unwilling weed eaters.

The pair that we kept, dubbed Papa Goose and Gertie, grew large and elegant. At first, they hung out in the front yard and liked to camp on the front doormat. The whole front porch was soon awash in goose poop. Not good. We fenced an area off our deck that became their pasture, then built a little pond and a house for them. I even bought a series of exotic ducks to keep Papa and Gertie company.

Our most successful vineyard experiment was far less glamorous: testing various grasses as potential cover crops between the grape rows to prevent erosion. Ours was one of a handful of vineyards that worked with the US Soil Conservation Service and Oregon State University to test a variety of perennial and annual grasses. We later learned that the level of cooperation between these two groups for this project was unprecedented. Apparently, it was uncommon even to have two different departments at the university working together.

My goal was to find a grass that would prevent erosion, would not compete with the vines for water since we didn’t irrigate, and would be stalwart enough to withstand equipment driving over it. From among the eight different perennial grasses we tried, we identified a sheep fescue called Covar that did all those things and, in addition, never grew more than four inches high. I sowed that wonderful little grass as a cover crop on our whole vineyard, as did many other farmers.

The US Soil Conservation Service recognized my work in 1984 by honoring Sokol Blosser as Cooperator of the Year for the Yamhill Soil and Water Conservation District. We were to be recognized and presented a plaque at the annual awards dinner. Bill and I both went to the dinner, but I might as well have been invisible. People looked right past me and came over to congratulate Bill and ask him about Sokol Blosser’s project. They assumed the farmer and decision maker was the man, as of course it usually was among the local farmers.

Before and during harvest, it was always a challenge to keep the wild birds away. Cedar waxwings and robins especially loved the ripening grapes. Cedar waxwings move in large flocks, flying like a squadron of small planes. Their elegant descent on the vineyard, in perfect formation, belied the damage they were about to do. I admired their grace and they were easy to scare, so it was hard to dislike them. Robins were a different story. Plump and wily, robins acted alone rather than in flocks, but there were many of them in the vineyard, and they were voracious grape eaters. They would hide in the leafy canopy when they saw us, and then go back to eating when we had gone. When I walked the vineyard with our dogs, Bagel and Muffin, they always took it as a personal affront when they saw birds in the vines and took off after them, barking ferociously. But even their most energetic efforts did not solve the problem.

We had tried everything else to warn off the birds: driving the pickup around honking the horn, riding bikes down the rows and yelling, tying a helium balloon with a picture of a hawk to a trellis wire, turning on an electronic device that emitted bird distress calls, even shooting an air cannon.

Air cannons now operate off propane canisters, but they were more elaborate and difficult in the early days of our vineyard. Water dripping on carbide rocks in a sealed chamber created acetylene gas. When enough pressure was built up, a lever would cause a wheel to strike a flint to ignite the gas and create a giant “kaboom.” They were not reliable and had to be checked often. Maintaining those cannons meant working on hands and knees in the mud during Oregon’s rainy fall season. Bill would light them in the mornings before he left for work and I would keep them going during the day.

I had just finished pounding posts for our new plantings and as I returned to the equipment shed, little Alison ran out to greet me. This remains one of my favorite mother-daughter photos.

I hated and feared guns, but finally I learned to shoot a shotgun to scare the birds; it was the only thing that seemed to work. In the early morning and in the late afternoon, the birds’ feeding times, I’d go out with my shotgun and my ear protection in our little off-road vehicle called a Hester ag truck. A cross between a four-wheel ATV and a golf cart, it had big knobby tires to traverse the vineyards, a bench seat so two people could ride, and a three-foot-square bed behind the seat for supplies. When Alison was little, we went into the vineyard to scare birds every morning after the boys got on the school bus. I bundled her up and she sat in the supply compartment, holding on to the sides with both hands. We bounced up and down the vineyard rows, two fearless females protecting our crop. When it was time to stop and shoot, I put big earmuff protectors on her and popped the shotgun a few times. The birds left unscathed but the noise scared them and I had the satisfaction of doing something about the bird problem.

Harvest season is always the most stressful time of year. The birds can eat the whole crop, the weather is changeable, and I am acutely aware that the future of the wines hinges on my picking decisions. Every year has its own twists and turns, but when I think of harvests, my mind always jumps to the disaster of 1984—the harvest from hell.

That year an unusually cold and wet spring had delayed bloom until mid-July, almost a month late, so we knew harvest would also be later than normal. We would have to depend on Oregon’s classic Indian summer to finish the ripening process. In early October, I walked the vineyard monitoring the grapes. Plump Pinot Noir clusters hung in neat rows along the fruiting canes. They had turned purple, the first sign of ripening, but they were still tart and did not yet have the taste I knew they could acquire. We needed at least two more weeks of good weather to achieve the quality we needed. We never got it.

The rain started a week later and seemed like it would never stop. As the cold gray rain pelted the vineyard, I sat inside, frustrated, helpless, and miserable. I tried to keep myself busy, but all I could do was look out the window and worry, hoping that the next day Indian summer would arrive. I passed the time by baking, then eating, cookies: chocolate chip, butterscotch chip, oatmeal. Between the rain and my overeating, I was a colossal grouch.

After a week of heavy precipitation, it finally stopped; I went out to inspect the damage. A rain-forest dampness hung in the foggy air. The ground was so soggy that I knew we couldn’t get a tractor into the vineyard; it would have slid around on the hillside. The grapes tasted watery, their flavor diluted. The forecast was for more rain. I couldn’t believe it. What had happened to our Indian summer? We had always wondered which season was most critical and the consensus had been that they were equal in importance. The harvest of 1984 showed us that one season mattered most: Oregon’s typically long, warm autumn was the secret to its great grapes.

After agonizing whether to act now or take a chance the weather would improve, I decided to pull in the harvest. When we brought in the Pinot Noir, it had absorbed so much water it was almost 40 percent heavier than we had forecast. Then, the storm began again and we had to harvest the Chardonnay in the rain. I felt apologetic for the pickers who had to slosh uphill to the ends of the rows toting two buckets full of grapes, over thirty pounds each since we couldn’t get the tractor onto the steep slope at the lower end of the rows. We paid them extra to pick under those terrible conditions, and our picking contractor had boxes of fried chicken for his crew when they finished.

The wine reflected the watery harvest. Since vintage-dating a wine (vintage records the year the grapes were picked) denotes a more premium wine, we decided to declassify the wine by producing only a nonvintage Pinot Noir that year. This was our way of letting people know we didn’t think the wine was good enough to deserve vintage dating. I get a sinking feeling in my stomach every year that we get rain in September. A disaster like 1984 is always just a rainstorm away. When the sky is dark gray and the rain is coming down steadily, it’s hard to imagine sunny weather returning. But it always has, except for that one year, wedged in between the two stellar vintages of 1983 and 1985. The memory reminds me how dependent on Mother Nature we are.

I worked enthusiastically with my vineyard crew for the 1980s. We farmed the vineyard and the orchards, and planted more acres of grapes when we took the orchards out. We created a wine grape nursery and sold our grape cuttings to new vineyards arriving in the valley. We researched cover crops, pruning, trellising, and canopy management. With all that attention, the farm became profitable for the first time by the end of the decade, twenty years after we started.

IN THE EARLY 1980s, when our small group of local wineries decided to band together to form the Yamhill County Winery Association, our first joint project was for each of us to host an open house at our winery during the three days after Thanksgiving. The weekend became a wine country tradition, copied later by county winery groups all over the state.

The original nine wineries (Adelsheim, Amity, Arterberry, Chateau Benoit, Elk Cove, Erath, Eyrie, Hidden Springs, and Sokol Blosser) advertised together in Portland, Salem, and Seattle newspapers to lure people out to wine country. People were glad to get out of the house and show off Oregon’s newest industry to visiting friends and relatives. As the number of participating wineries grew, so did the number of visitors and the popularity of wine touring.

“Wine Country Thanksgiving” became our biggest retail weekend of the year. After the initial years of welcoming visitors in our small tasting room, we had to move the event into the larger winery cellar to handle the crowds. We served food, offered tastes of all our wines, lowered prices for the weekend, displayed holiday gift baskets, and brought in neighboring farmers to sell their chocolate-covered hazelnuts, flavored honey, marionberry preserves, and Christmas swags and wreaths. Holiday greens, wooden lattice, and bright red poinsettias helped mask the production equipment of tanks, barrels, catwalks, and refrigeration pipe.

Sometimes I wondered what it would be like to go away for the Thanksgiving holidays, or to be free for shopping or whatever we felt like doing. It wasn’t an option. Wine Country Thanksgiving was too important to our business, so we made it a family event and tried to make it fun. In the early years, Bill’s mother, Grandma Betty, took charge of the tasting room kitchen, which was separated from the main space by a long counter on which she kept a large coffee urn for nondrinkers and designated drivers. She was adept at chatting with visitors while attending to her main job, slicing French bread to go with the cheese on the food platters. Tired of arm cramps from slicing baguettes to feed the increasing crowd, she showed up with a gift for the winery—an electric bread slicer. Bill’s father, Grandpa John, helped pour wine, stopping occasionally to chat with former patients who were delighted to see one of their favorite doctors. Usually they wanted to hang out at John’s table and talk, and we had to rescue him to keep the tasting line from backing up.

Nik, Alex, and Alison did whatever they were able to do, making change at the admissions table as soon as they were old enough, and later, when they were older and stronger, restocking wine, washing glasses, and carrying cases out for customers. Before we had a full-time bookkeeper, we made a custom each night of counting the day’s take. We brought the small gray metal cash box home and gave the kids the honor of doing the counting. They sat on the floor in the living room and learned, at an early age, how to put the bills in order, all facing the same way, how to count the change, arrange the credit card receipts, and fill out the cash-box records.

We were always on the lookout for vineyard or winery projects we could tackle as a family so the kids could be involved. One year Grandma Betty showed us an advertisement in a Christmas catalog for a package of shredded grapevines to be used as smoke flavoring for the grill. She brought it as a curiosity, but teenage Nik seized on the idea, and NGB (his initials) Enterprises was born. He tackled the production side, and I agreed to help with the packaging. We would sell it in the tasting room.

Production started that February, as Nik and Alex (NGB Enterprises’ first employee) pulled the vine prunings out of the vineyard rows. They kept the Pinot Noir and Chardonnay separate and transported the big piles of prunings down to the shed to dry out. Nik used the money he earned working at the winery to buy a shredder to shred the prunings to the right consistency. The shredded prunings, which we called Grapevine Smoke, dried in wooden totes until the family (free labor) could get together to bag, seal, and label our new product.

I got carried away designing the packaging. I pictured people grilling with Pinot Noir Grapevine Smoke and then drinking Pinot Noir with their meal, so I decided to package the smoke and the wine together, in a two-bottle wine box. This required putting the new product in a long, narrow, special-order plastic bag that, when filled, would be about the size of a wine bottle. And if there was to be a card for the directions (simple: soak in water before putting over the coals on the grill), why not print recipes on the other side? I found a woman to create recipes for both the Pinot Noir and the Chardonnay. When she tried out the two different Grapevine Smoke samples, she called to say, “I never would have guessed how striking the taste difference was between the Pinot Noir and Chardonnay smoke. It’s amazing!”

The final step was to have a colorful label designed and printed. I spent more time on this project than I had intended and did all the running around, since Nik wasn’t old enough to drive. But I enjoyed the challenge. We sold the individual bags in the tasting room and made up gift boxes with the wine and matching Grapevine Smoke.

The next year we decided to offer our new product to Norm Thompson, a Portland catalog company whose slogan was Escape from the Ordinary. Nik and I visited the Norm Thompson headquarters to pitch the new package we had devised—a slatted wooden crate containing one bag each of Pinot Noir Grapevine Smoke and Chardonnay Grapevine Smoke shrink-wrapped so that the products, labels, and recipe cards were clearly visible. To our delight, their buyer loved it and ordered one thousand boxes.

We had made only a hundred bags of each type of Grapevine Smoke the first year, but Nik and I jumped at the chance to be in the prestigious Norm Thompson catalog, and ignored the logistics of increasing production by a factor of ten. Production went into high gear. Every weekend the extended family gathered in the equipment shed to tackle the mounds of shredded, dried grapevine prunings. As the rain pounded on the metal roof, we ran our little assembly line and managed to keep our good humor, as long as we could see progress. I applied our fancy self-stick labels to the plastic bags, then Grandma Betty, Grandpa John, and Nik, in white dust masks, filled them with the Grapevine Smoke. Bill ran the temperamental hot sealer to close the bags. Alex put the bags in the crates so they could go to Portland for shrink-wrapping. Alison was too little to do much but play and get in the way. The final product was impressive and we were proud to see it in the catalog. Nik made enough money to buy himself a used car. But that was the end of the Grapevine Smoke caper. Nobody was willing to do it again.

Growing up around the winery meant a lot of watching Mom and Dad pour wine for customers, talk about the wine, and sell it. Kids are nothing if not imitators, so I guess it was natural for me to want to copy them and sell something to customers, too. Since the cherry trees on our farm happened to be in season, I decided cherries would be what I would sell. The tasting room was open only on weekends, so if I wanted to do this, it would mean giving up watching Saturday morning cartoons, but I decided getting up early to pick the fruit and pack it in the little green pint fruit cartons, ready to sell to customers, would be worth it. I was probably eight years old. I thought I had told Mom what I was planning but she looked surprised when she found me setting up shop at a picnic table outside the tasting room with my baskets of cherries and free samples.

Then, one May when I was nine years old, our local volcano, Mount Saint Helens, spewed ash across the western US. My brother and I took advantage of this opportunity, collected buckets of ash, put it in little plastic baggies, and sold them to visitors as genuine Mount Saint Helens ash souvenirs.

My next venture was “Grapevine Smoke.” Mom had heard about using chopped up grapevines for barbecuing to add smoke flavoring. This ended up being our most complicated venture to date, with recipes, a chopping and bagging operation, and ultimately placement in a catalog for home chefs. The Grapevine Smoke business earned me enough money to buy my first car, after I was old enough to get my driver’s license. The catalog company eventually stopped ordering, I went off to college, and I gave the car to my brother, who I felt had earned it from all his labor helping me.

Nik Blosser

Chairman of the Board, Sokol Blosser Winery

The Newport Seafood and Wine Festival, which took place in the city of Newport on the Oregon coast in February, was another family event. The Newport Chamber of Commerce started the festival in the early 1980s to lure people to the coast during the winter, and we supported it for many years, spending the weekend at a local motel. Bill’s folks went along. John helped us pour wine while Betty entertained the three kids. She took them to the aquarium, the wax museum, and the beach. I know her job was harder than ours. Every morning, before the festival started, all of us went to a local restaurant famous for their poppy-seed pancakes. It was as close to a vacation as we got for many years.