Читать книгу Kippenberger - Susanne Kippenberger - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

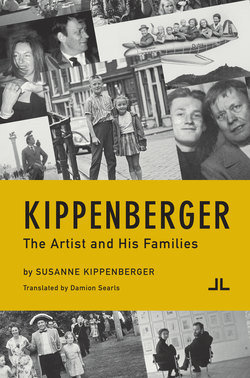

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

MY BIG BROTHER

He was my big brother. My protector, my ally, my hero. Whenever I got into a fight with my sister, I only had to yell “Maaaartin, Bine is...” and there’d be something, a “Cologne Cathedral” (Martin yanking poor Bine up by the ears until she was dizzy) or an Indian burn. He wrote me letters like this from his boarding school in the Black Forest: “Dear Sanni, How are you? I think about you every day. Are you baking cake yet? Don’t snack so much, you’ll get a tummy ache. Do you brush your tiny teeth every night? I hope so.” He was ten at the time; I was six. Now I’m 54, ten years older than my brother was when he died.

It was on March 7, 1997. Almost exactly the same people came to Burgenland for his funeral as had celebrated his marriage with Elfie Semotan there a year before.

He was so looking forward to 1997—it was going to be his year, his big breakthrough at last. A “Respective” in the Geneva Museum in January, then a few days later the opening of The Eggman and His Outriggers in Mönchengladbach, his first solo show at a German museum since 1986. In March, the Käthe Kollwitz Prize and an exhibition of his Raft of the Medusa cycle at the Berlin Academy of Arts, then documenta in June, and the sculpture exhibition in Münster—but he didn’t get to see those. Hepatitis, cirrhosis, liver cancer: six weeks after the diagnosis, he was dead.

Is it possible, advisable, permissible to write about someone so close to you? My first reaction, when asked if I could imagine writing about my brother, was No! No no no.

Yes.

Martin Kippenberger is a public figure. A pop star, a brand name, a classic contemporary artist. He is written about, spoken of, and judged. Newspapers and magazines that kept deadly silent at best about him while he was alive now praise him. And he—who let nothing escape comment—can no longer say anything. Night and day (especially night), he used to manage his image as an artist, but now he has lost control. That is what he was most afraid of.

He shows up as a character in novels, there is a hotel suite named after him, a play, a restaurant, a guinea pig (at least one). You can buy him as a notepad. Ben Becker dedicated a song to him: “Kippy” on the album We’re Taking Off. His early death has turned him into a legend, especially for younger people—a kind of James Dean of contemporary German art. A devil for some, a god for others. The picture of the human being is fading away.

The picture we have of the artist, on the other hand, seems to be growing clearer and clearer. His work began to be taken seriously only after his death; now that it is finished, it can be viewed in peace, and connections within his body of work can be discovered and explored. Martin produced at such a pace that there was barely time to glance at his work when he was living. Now he has platforms he could once only dream of: the Venice Biennale, the Tate in London, the Museum of Contemporary Art in L.A., the Museo Picasso in Malaga, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. But posthumous fame was exactly what he wasn’t interested in. He wanted to experience and enjoy the success that he, in his opinion, deserved. He believed in himself from the beginning, in himself and in art.

People terrified of him while he was alive now say that Martin is no longer here to get in the way of his art. The shock of his sudden death was a wake-up call for those who had only seen the humor, not the seriousness behind it—and who couldn’t even laugh at that. Zdenek Felix, former director of the Hamburg Deichtorhallen, holds the humorlessness of German museum directors partly responsible for the fact that, between 1986 and 1997, Martin had solo shows at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Hirshhorn in Washington, the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco, and Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, but not one in a German museum. “He was too early,” says Tanja Grunert, the gallerist, “Martin was always too early.”

There are many different pictures of Martin Kippenberger, both public and private. He drew and painted lots of them himself, constantly had his picture taken, and put himself on display in bars and museums, at exhibitions and parties. He was often described as cynical, but he was a great moralist and humanist. In Berlin in the late seventies he was known as an impresario of punk and hard rock in the Kreuzberg club S.O.36, but in his studio he preferred to listen to the oldies: Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra. “My Way.”

He is sometimes described as an autodidact, but he learned his craft at the Academy of Arts in Hamburg, and broke off his studies only when they got to be too boring. No, he wasn’t an autodidact; he was a self-made man. He created himself rather than waiting to be discovered. “He was his own best salesman,” said the gallerist Bärbel Grässlin. But not everyone was buying: “He was not a good person,” the obituary in taz cruelly said.

For Martin everything, even his name, expressed his vision. As a boy, he was always allowed to ride on St. Martin’s horse during the St. Martin’s Day processions, and like the saint, he shared everything he had. Money, success, and influence; his sense of fun, his art, and his worries. When things were going badly for him, he got mean.

He knew how to hit home. “He saw through people like an x-ray,” a girlfriend says, and found all their weak points. He attacked the bad and defended the good the way a lioness guards her cubs. There were people who hated him and people who loved him in the burning depths of their hearts—the innkeeper’s daughter in Austria no less than the rich collector. Ever since Martin’s death, people have quoted his line: “I work hard so that people can say: Kippenberger was a good time.” And he usually was a good time, but woe to anyone around him when he wasn’t.

The image of the jolly entertainer masks the shadows underneath, and the fact that he worked himself to death creating this image and his work. “When you face an abyss,” he wrote on one of his pictures, “don’t be surprised to find you can fly.” His wild artist’s life seems thrilling from a distance to fans. He himself called it “insanely strenuous to be on the road with absolutely no private life.” Still, that’s what he did a lot of the time—lived as fast as a driver on the autobahn. Then, for a few days or a week, he would stay with friends or acquaintances who made him feel looked after and cared for. He wouldn’t constantly have to show off, but could show his weak side too, and be quiet.

In the early years he was constantly pulling down his pants, but few people ever saw him truly naked. How can I strip him bare now that he’s dead, and reveal his vulnerability, his fear, his doubts?

The picture of him we need to draw is more complex than either his enemies or his fans would like. As complex as his art. Who was my brother? An anarchist and a gentleman, one of the boys and a friend to women, big brother and little brother, a sole provider who was anything but solitary—yet perhaps, in the end, solitary after all. He attacked and undermined the art scene while playing along within it; he was someone who “simultaneously rejected and thoroughly celebrated the role of the artist,” as Diedrich Diederichsen said.

He was always something of a Rumpelstiltskin. He bounced through the art world as a collector, painter, impresario, museum director, installation artist, graphic artist, dealer, photographer, braggart, teacher, and puller of strings. For him, that was the freedom of art: to constantly overstep boundaries, including the limits of good taste. “Embarrassment has no limits.” His rituals for getting under people’s skin (the endless, pointless jokes; the swaggering, macho songs sung in groups that pointedly excluded women) were all tests: What are people willing to put up with, and when will they start to rebel? Do they know a joke when they see one?

The more horrible something was, the more he liked it as material for his art, from a flokati rug to Harald Juhnke, from a bath mat in front of the toilet to politics to Santa Claus. One critic said that Immendorff brought the German battlefields to the international art world, while Kippenberger brought German everyday life.

As he openly admitted himself, he made “kitsch” now and then. Rent Electricity Gas (the title of one of his shows) needed to be paid. He wanted to live well. The rhyme “ Nicht sparen—Taxi fahren ” (Don’t save money, take a taxi) was one of his favorite sayings. He never saved; he invested all his money in life and art, not bank accounts and prestigious purchases. He only got himself a BMW once, when he went to Los Angeles. In Hollywood, he thought, you have to flaunt it. He wanted the biggest BMW, with a chauffeur, of course, and when he could only get the second biggest, he glued the missing cylinders on the back, as top hats (“cylinder” and “top hat” are the same word in German). Martin arranged and reframed everything, from matchboxes to invitations to hotel rooms, leaving his mark everywhere. Walter Grond called it “kippenbergerizing the world.”

He farted at the table with important museum people—yet with Mrs. Grässlin in the Black Forest he behaved impeccably. Johannes Wohnseifer, Martin’s last assistant, worshipped Martin’s good manners, his “natural authority.” Many people experienced his excessive lifestyle in Cologne and Berlin, Vienna and Madrid, but not his periodic retreats to the Black Forest, or a Greek island, or Lake Constance, to carry out his “Sahara Program.” Every year he went to a spa for several weeks, where he ate only dry bread and drank only fruit juice and water. Afterward he could plunge back into his excessive life.

I wouldn’t call these contradictions—I would call them extremes. F. Scott Fitzgerald, another heavy drinker and romantic, described it this way in his autobiographical essay “The Crack-Up”: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” That was the intelligence Martin Kippenberger had, he who had never graduated high school. He always wanted everything—to have his cake and eat it too. I is another was the title of a major exhibition in which Martin was represented with several of his self-portraits, but “I am I,” is what he would have said, “and I am many.”

This book is not the full truth. It does not aim for completeness or uninterrupted intimacy, and certainly not for art-historical classification and interpretation. It does not fulfill the chronicler’s duty to cover everything. It is a portrait, not a biography. But everything here is true—is a truth, but not merely my truth. It is the result of numerous conversations with family, friends, museum curators, gallerists, artists, and critics. Truth Is Work [1] was the title of his exhibition with Werner Büttner and Albert Oehlen in the Folkwang Museum in Essen, the city where we grew up. This book sets out to understand how he became who he was—how the Kippenberger System operated. And also to remember a time when the collectors who now pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for a self-portrait wouldn’t have taken it for a fraction of that sum.

“Is the boy normal?!” his teacher asked, horrified, when faced with this child who did not see the world like a child—a nine-year-old with the wit and humor of an adult who still hadn’t learned his times tables and had never learned to write properly. He would rather look out the window than at the blackboard. “Martin, Our Artist” was written on the kitchen wall in our house when he was a boy. He never had to play the artist, which is why he could play with the role of the artist. What can art and the artist do, and what should they do: that was the guiding thread of his life. He tried out every possible artist role; he took the famous line from Beuys, “Every human being is an artist,” and flipped it on its head: “Every artist is a human being.”

No, he was never normal. He burned like the cigarettes he seldom failed to have in his hand. “Howdy-do!” he said in the morning to the retirees at the Äppelwoi cider bar in Sachsenhausen, and with another “Howdy-do!” he stood in the door of Bärbel Grässlin’s gallery a few hours later, looking for someone to join him for lunch. “Howdy-do!” he yelled into the telephone in the evening—after his afternoon nap, which was sacred—and so it went on: eating noodles, having a good time, working, and dancing until dawn. At 7 a.m. he was standing ramrod straight in the Hotel Chelsea in Cologne, saying his hellos in Chinese. He had already danced a little jig around the cleaning lady, and now he greeted the Chinese hotel guests, hands folded across his breast, bowing to each one. They may not have thought it was funny, but he did. A few hours later he was back at work.

The people with him laughed and suffered. Anyone who went out with him at night knew there was no way they would get to bed—Martin was merciless.

He could never bear to be alone, except maybe during his afternoon naps or when he was painting. Big Apartment, Never Home is the title of one of his pictures. As soon as he moved somewhere—and he was constantly moving from one city to another: Hamburg, Berlin, Florence, Stuttgart, Sankt Georgen, Cologne, Vienna, Seville, Carmona, Teneriffe, Frankfurt, Los Angeles, and the Burgenland—he immediately sought out the local bar that would become his living room, dining room, office, museum, studio, and stage. His hometown headquarters was the Paris Bar. Its owner, Michel Würthle, was his best friend.

His hanging around in cafés was actually all about “communication, communication, communication,” according to Gisela Capitain, his gallerist and executor. The “Spiderman,” as he once portrayed himself, spun his nets everywhere, day and night: “Martin was always on duty.” Truth Is Work: that was another boundary he crossed—the one between life and work, between himself and others. “On the whole and plain for everyone to see I’m basically a living vehicle.” Every party was both a stage for his performances and a source of raw material for his new works. That is why it is so hard to answer the question of who my brother was. The person cannot be separated from the artist—he turned almost his whole life into art. Many people could not distinguish between the artist and the person, but still, it is important to avoid simplifying his art by seeing it merely as reflecting his life. (Anyone who thinks they can reconstruct the stations of Martin’s biography with his drawings of hotels falls right into his trap: he drew pictures on the stationery of many more hotels than he actually stayed in.) The art was not a reflection of his life, it was his life.

He was an only son with four sisters; a boy who was not like other boys, who painted and cried and would rather play cards than play with cars (this would later bring in a fortune as an adult). He was the only one of us children who enthusiastically took part in our father’s staged photographs, but at the same time he never took direction. He coquettishly struck a pose, arms flung around a lamppost and one foot pointing up in the air behind him. His eyes sparkled in the photos the way they always did: enjoying himself, giving off sparks of energy. He was like that from the beginning: funny and charming, difficult and uncomfortable, cocky and uninhibited and free.

Again and again he got into fights with his family. He suffered when our parents sent him to boarding school; he never felt sufficiently loved, acknowledged, and supported. But he was always attached to them. This terror to the bourgeoisie was a family man through and through; the enfant terrible rushing around the world also cherished the family traditions. Our mother died young, and he gave his daughter her name; our father’s signet ring with the family coat of arms never left Martin’s finger. He always insisted that we all celebrate Christmas together and clung tightly to the rituals: there had to be presents and a big Christmas tree and turkey dinner—and no question about who would get the drumstick. He even came along to church sometimes; he never officially left the church. He hated routine and tried something new with every exhibition project, yet he needed rituals the way a drunkard needs lampposts.

He always said he wanted a large family of his own, but he couldn’t handle life as a paterfamilias for long after his daughter was born.

Martin never lived in a pure artistic sphere. He brought us, his thoroughly unglamorous family, everywhere—to tea with Rudolf Augstein, publisher of the news magazine Der Spiegel, when we were still practically children; to luxury hotels in Geneva, where he got us free rooms; to the wild party celebrating his opening at the Pompidou Centre. “Are you coming?” read the invitation, and woe to those who didn’t. He would feel as hurt as a little boy. He had our mother stay in his substance abuse halfway house, and showed work with our father.

The enfant terrible really was a child his whole life, one who gathered families around him: friends, collectors, landlords and landladies, fans. He could beam with pleasure, sulk, run rampant, lose his temper, and be unfair, like a child—but then, the next day or next year, own up to it like a man and publicly apologize. He threw himself at our grandmother during a summer vacation once—through a glass door that he was too excited to notice—and would later throw himself into ideas and projects the same way, sometimes causing as much pain as the broken glass did back then.

He could be greedy, jealous, and egocentric, but also proud, of himself and of many other people, of their art, their craft, their cooking. He didn’t just brag about himself. And he wanted presents like a child, too. For his fortieth birthday, an orgy of spending and dissipation, he wanted a Carrera slot-car racetrack; he would stand under the Christmas tree with shining eyes. “Childhood never really ends,” he said in an interview with artist Jutta Koether.

He was extremely intelligent but never an intellectual. He read the Bild tabloid and Mickey Mouse comics, not Roland Barthes and James Joyce. He drew his material from popular culture. He let someone else read Kafka and tell him about it, the way he let others travel and draw and build sculptures for him. He would discover things lightning-fast, seize on ideas, and assimilate them. If there was something he couldn’t do in the morning, he would show people that he had learned to do it by the afternoon: make etchings, play the accordion, speak Dutch. It wasn’t real Dutch, of course, but it sure sounded like Dutch.

“Think today, done tomorrow” was one of his most well-known sayings. It was only half true. His major projects, such as The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika,” percolated for a long time before they were ready. One year he would paint three or four pictures; the next year, forty or fifty.

He overflowed with ideas that no one else had, or if someone else did have them, he simply appropriated them, whether they came from Picasso or his students or his daughter, Helena. He was as generous in taking as he was in giving, and he always demanded from others what he himself offered: everything. “You had to take care not to turn into a Kippenberger slave,” Bärbel Grässlin said.

He wanted fries and croquettes served at the opening of his exhibition at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam because that’s what we ate on our summer vacations in Holland, every night for six weeks. The museum would have preferred tomatoes and mozzarella but Martin had nothing but contempt for such things. He hated the prevailing fashions—postmodern architecture, arugula, shoulder pads, video art. Whatever was “in” was “out” for him—good only for material. Political correctness disgusted him. He built postmodern houses out of plywood and glued lighters all over them, or produced a multiple for documenta: a white plate with a big hole in the middle, “ Ciao rucola mozzarella tomate con spaghettini secco e vino al dente. ”

He likewise discarded his hippie look early and cut his hair short, put on a tie—unheard-of in Kreuzberg in the seventies—and wore only the finest suits and most expensive shoes, even in the studio. Clothes, too, were a costume. He wanted to be a walking contradiction to everything people expected from a crazy artist. Aside from that, he liked to look good, at his best like the Austrian actor Helmut Berger. He loved to hear people remark on his similarity to Visconti’s leading man. He would have loved to be famous as a movie star, or a poet. Opera and theater didn’t interest him. But movies! He knew the Hollywood classics by heart, even years after he’d seen them, and could recall scenes in the most minute detail. “Anyone who saw him in action, ranting and raging, swinging his mic onstage at 5 a.m., could see his genuine, abiding star quality, a charisma which happened to have been diverted into the art world,” said the obituary in the Independent.

In his worst periods he looked like a shabby artist: unwashed, drunk, and fat. So he pulled his underpants up over his belly like Picasso, stuck out his paunch, had a photo taken, and turned it into an exhibition poster, or a painting, or a calendar. Every weakness became a strength when transformed into art, even if the pain remained. When punks beat him up in Berlin, he had his picture taken with his bandaged head, swollen face, and crooked nose, and later painted himself like that, too. He titled it Dialogue with the Youth, part of a triptych called Berlin by Night, and he also used it as an admission ticket; he loved repurposing things as many times as he could.

He was a child of the Ruhr District, the industrial center of Germany that gave him his directness, fast pace, and dry humor. He liked how people there interacted with each other naturally and honestly. They were raw and unsentimental, always aboveboard, never stuck-up. He was an absolute master of the notes on the social keyboard, but he didn’t divide people into important and unimportant. When his neighbor, a good, honest photographer, didn’t understand Martin’s art, Martin explained it to him seriously and in detail. He met everyone at eye level, whether millionaires or children, neither looking up at them nor looking down on them. That is why children loved him so much. They also often understood his humor better than the critics and curators, and didn’t automatically feel offended by his outrageous sayings and provocations, which, in his friend Meuser’s view, were “just his way of saying, ‘Hello, so who are you?’”

He liked to quote Goethe and our mother: “From my darling mother my cheerful disposition and fondness for telling stories.” From her also came his generosity, social conscience, and pleasure in meeting new people no matter where they came from—the ability to see what was special about others no matter what form it took. From our father he inherited artistic talent, a tendency to excess, lack of inhibition, and love of enjoying himself, self-presentation, staging scenes. Artist Thomas Wachweger coined a word, Zwangsbeglücker (someone who forces others to have fun), that fit both father and son.

He was full of longing. He craved drugs, then alcohol; recognition and attention; love, TV, and noodle casserole. Martin asked lots of mothers to cook him our mother’s noodle casserole, and of course turned it into art, too. Kippenberger in the Noodle Casserole Yes Please! was the title of one of his first exhibitions, in Berlin. “Addiction [ Sucht ] is just searching [ suchen ],” he explained to Jutta Koether in an interview. “I reject everything and keep searching for the right thing.”

“Man Seeking Woman,” along with his photograph and address, was printed on the sticker the size of a visiting card that he put up all over Berlin in the seventies. It was more than a good joke—behind the irony was a deeper seriousness. He called one of his catalogs Homesick Highway 90, and on the title page was a picture of him with our father crammed into a photo booth. Homesickness and wanderlust; longing for a place to call home and running away to be free of all ties, obligations, and labels; the desire for peace and quiet and the restless curiosity and dread of boredom; the paradox of wanting to be recognized, wanting to belong, but not wanting to be pigeonholed. That was his lifelong struggle.

Self-portrait in friendship book, 1966

© Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

In the sixties, little girls used to stick glittery roses, pussy willows, and forget-me-nots into friendship books and copy out little didactic verses alongside: “Be like the violet in the grass / modest and pure in her proper station, / Don’t be like the prideful rose / always wanting admiration.” My brother drew a caricature in my album of German chancellor Kiesinger (“big”) on the left, de Gaulle (“bigger”) in the middle, and on the right, at the top, on a victory podium and with a wide grin on his face, a beaming man with elephant ears and a crew cut: unmistakably Martin. His little poem: “Love is like an EVAG city bus / It makes you wait and doesn’t care / And when at last it hurries by / The driver yells ‘Full!’ and leaves you there / Your [and then in a heart:] big brother, Martin.”

Everything about Martin is here: the humor, the mockery, the irony (directed at himself, too). His poking fun at pretense and his lack of respect for power, along with his own ambition and boastfulness. His linking the banal with the elevated, and kippenbergerizing an existing rhyme with a personal detail (“EVAG” stands for Essener Verkehrs AG, the Essen transit authority). The longing for love, and the fear of being excluded from love and remaining alone. The draftsmanship, the tenderness, and the pride he had in being a big brother.

[ 1 ] A rhyme in German: Wahrheit ist Arbeit.