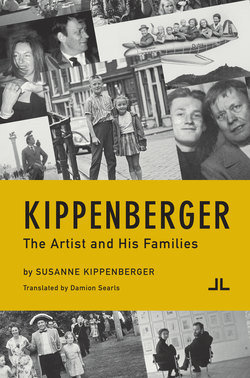

Читать книгу Kippenberger - Susanne Kippenberger - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

PARENTS AND CHILDHOOD

“He was running away.”

The answer came before I even asked the question: How did it happen that he went and stayed with you when he was so young, just nine years old? His first long trip away from home, going with total strangers all the way from deep in the Ruhr on the western edge of Germany to deep in the Bavarian Forest in the east, near the Czech border—what was that like?

“He couldn’t wait,” she says.

He wasn’t coming to see her—he was leaving where he was.

Our parents and Wiltrud Roser barely knew each other. Our mother had written a letter to the artist just six months earlier, the first of many that would travel from Essen to Cham. “Dear Wiltrud!” she started the letter—to a woman she didn’t know, and didn’t know anything about except that she illustrated beautiful children’s books. All she knew was Waldemar, Roser’s illustrated dog.) “I’m addressing you by your first name because it’s right either way: I don’t know if you’re a Miss Roser or Mrs. Roser, and you’d be offended (actually you probably wouldn’t be, but you might be) if I wrote the wrong one.” Our mother definitely didn’t want that, since she wanted something else from this stranger: a picture. She wanted to surprise our father for Christmas with a family portrait just like the one in Waldemar. He might well have come up with the same idea himself—“that happens to us a lot, that we plan the same surprises for each other”—and if so, Wiltrud should say yes to her and no to him.

Instead of a photograph for Wiltrud to copy, she sent short descriptions:

Dad: broad-shouldered and stocky

Mom: no distinguishing characteristics, like all mothers

Barbara (“Babs”): 11 yrs old, thin, bangs, strawb. blond short hair, freckles & a very critical look

Bettina: 10, strong, long dark blond pigtails, maternal, head usually tilted

Martin (“the Boy”): 8, short hair, lots and lots of freckles

Bine (Sabine): 6, short and stumpy, blocky head like Dad, light blond pigtails & an electric socket in the middle of her face

Little Sanni (Susanne): 4, dark blond pigtails, clever

“Will you do it? It would be great! We are such a crazy and fun family that we would probably give you a ton of material for more children’s books.” Our mother wrote that she had already met many Munich artists in similar fashion and had become friends with them. “I think you’d be a good fit with us too.” Would Wiltrud ever have the chance to come to Essen for a visit?

Wiltrud Roser drew the picture, which still exists, and she came to our house for an artist party. The next morning the two women sat at the breakfast table coming up with plans for everything Wiltrud should do in the big city: plays, museums, and more. And then our mother said she didn’t know what she was going to do, Martin simply refused to go to school anymore. He was sick, too. “Incredibly pale” is how Wiltrud Roser remembers him. He was suffering from what our mother called the proletariat sickness or Ruhr anemia: a sallow, bloodless face. “The sky was yellow in the Ruhr”; the chimneys in Essen still spewed smoke then—fresh-washed clothes were black if you left them hanging on the clothesline for a few hours.

In Bavaria, the sky was blue.

“Why doesn’t he come with me?” Wiltrud Roser said. She had a son, too, just a year younger than Martin, and the school year was almost over anyway.

“Martin, would you like to come home with me?” she asked him when he came into the kitchen.

“When do we leave?” he answered.

So that was that. No more plays, no museums, no shopping trip to the big city—Martin was determined and didn’t give Wiltrud any peace. They left the next day for practically the outermost reaches of the German world, a little town where teachers and students were often transferred as punishment.

Our family as drawn by Wiltrud Roser

© Wiltrud Roser

The address couldn’t have been more perfect: 1 Spring Street (Frühlingstrasse 1). He liked the old house with all its nooks and crannies, right on the Regen River, with a sawmill out back—a giant, adventure-filled playground. It was a house like ours: cold in temperature but warm in every other way, full of pictures and books, with little wooden figures standing around everywhere, even in the bathroom. Albrecht, the father, was only a distant figure—he worked as a puppeteer in Stuttgart; the aunt was a Chiemsee painter; Wiltrud worked on her picture books; the grandmother took care of the children. Martin did what he would so often do later in life: he got other people to work for him, hiring Wiltrud’s son Sebastian to do his homework. His grades in math and writing improved, though only temporarily—school remained torture for him and for everyone around him. The boys spent a lot of time with Wiltrud in her studio, each one busy with his own picture. One time, “with a fabulous gesture,” Martin swept everything in front of him off the tabletop.

“Martin, what are you doing?!”

“Making room.”

And, she thought, he was right. Other people might have called it naughty. She called it kingly. “He was never bad, just kingly: bossy but generous.”

He sat for her as a model, too, and our mother said that when the book with those drawings came out, he showed it “to everyone, whether they wanted to look at it or not.”

Martin was “terribly easy to take care of,” a darling boy, and Wiltrud, a short woman with short hair, cheerful and sassy and always a straight talker, was certainly right for him. At eighty she can still laugh about the gaudy kitsch in the Cham Catholic church. She has lived in Cham her whole life, in her parents’ house at the edge of a small town, but has few ties with the locals. She just lives there.

She told me that Martin wasn’t homesick, “not at all,” but that he made presents for his sisters the whole time he was there. Martin stayed six weeks; it seemed like months and months to her. And at the end of the stay he went back to Essen just as eagerly as he had left.

The thank-you letter that our mother sent to Wiltrud Roser sounds euphoric: Martin regaled the family with his stories, like the one about Vicar Bear and his cane, until we cried with laughter. “Already on the first morning he danced the polka, around to the right and around to the left, in his long nightshirt, it was a scream. He can sure dance, and paint too!” He’d been painting what he had seen in Bavaria, including Sebastian (“it couldn’t have been any more like him”) and Vicar Bear (“who looks terrifying”). “His stay with you was so good for him, in body and mind and spirit, that I can’t thank you and everyone else in Cham enough.”

Delight over his scholastic progress didn’t last long, in any case. After summer vacation Martin went back to school in Essen-Frillendorf to repeat third grade. Everything was like the old days again, and soon he would be sent off to a boarding school in the Black Forest, and from there to the next boarding school, and so on.

The Rosers were his first “second family,” and he kept in contact with them. Cham was the beginning of his life far away from home. One of his most haunting self-portraits is called Please Don’t Send Home : Martin peers out like a little runaway child, with no home any more, imploring the viewer to take him in because there is no going back. He wanted to move forward, get ahead, achieve something, conquer ever-new territory.

Still, according to his friend Michel Würthle, there was one place among all the many places in his life where he was always happy to return: “Childhood. The family house. Mama and Papa.”

OUR PARENTS

A person doesn’t create himself out of nothing, after all.

—MK

[Did your parents play a part in your personality?] Massive, massive, massive. I have to admit it. A huge part.... Both parents. Both extremes.

—MK

They fell in love with each other through writing. Writing letters.

Actually, they had already known each other for a long time: they were in the same dancing school without really noticing each other. Their parents moved in the same circles in Duisburg. And long before he received letters from her himself, he had read her letters.

It was during the war, in Hungary, and the doctor in his regiment, one Wiechmann, always showed him what she’d written. Wiechmann didn’t know what to make of the dry letters and couldn’t understand why he wasn’t getting anywhere with her. The young lady just wouldn’t catch fire. Our father gave him good advice but it didn’t help.

Later, after the war was over, our father’s father invited her over to dinner—not without thinking, perhaps, that she might make a good match; he would have known that as a manager at Deutsche Bank. After a stroll in the woods, our father took her to the streetcar: “the only thing I remember was her unusual way of walking. She just galumphed along.” He found it touchingly awkward. And that was that, until he wrote to congratulate her on her recent graduation from medical school, just to be polite. She wrote to thank him for his thanks, “and from that bungled thank-you-no-thank- you ” arose an exchange of letters.

He gently accused her of maybe being too cold to the other man, Wiechmann, and our mother got furious: she had only written to him on the front in the first place out of pity! But then, wounded in his masculinity, this Wiechmann had started insulting her, accusing her of being a “sexless workhorse”—her, Dr. Lore Leverkus, a young doctor who had just started her first job at the Göttingen Clinic for no salary because the paid positions were reserved for the men returning from the war. “I don’t care to answer letters like that.”

The two of them debated the meaning of love and discussed art. She told him about Beethoven concerts she had heard, live or on the radio, and he told her about the pictures he was painting and the classes he was taking. “A ten-page letter two or three times a week,” our father said later, “no one can withstand that.” For his twenty-sixth birthday, March 1, 1947, she typed up their letters, bound them, and gave him the volume, illustrated with the little pictures he used to send her to accompany his words. She wrote as the dedication “You for me and me for you.” And next to the dedication was a bookplate he had drawn for both of them to use: someone sitting in an armchair and reading a newspaper that said “Lore” on one side and “Gerd” on the other.

They called each other “Little Man” and “Little Mouse.” She sent him care packages with oatmeal, bacon, textbooks, ribbons, brushes, and Rilke poems. He, a mining student in Aachen, sent her stockings, and also work: reports to type up and send on to the senior office. He sent her drawings and watercolors, which she tacked to the wall of her room. Whenever he painted, “burning with zeal,” he forgot everything, including the stove he was supposed to keep hot while she cooked for him and did the laundry. Sometimes she read to him while he was painting. Art, he would later say, was what he had really wanted to study, really wanted to do. If only the war hadn’t gotten in the way.

When she was offered a position in Odenwald, she turned it down: “There’s not the slightest intellectual stimulation there, I’d go brain-dead.” She liked to go to concerts, to the theater—a Shakespeare production in a ruined cloister, for instance. She was an enthusiastic reader of what people were reading in those days (Manfred Hausmann, Frank Thiess), and she liked telling him, a “specialist in the field,” her impressions of various art exhibitions in Wiesbaden. She worshipped the Old Masters (Dürer, Grünewald, Bosch) and complained about contemporary artists: “All their works have nothing to say except ‘Me, me, me.’” Within six months, she had revised her opinion and said she recognized genius in modern painting; she didn’t want to “label it as smears of color on the wall any more.”

In one of his early letters, Gerd had told her that he was more afraid of marriage than of the war. But on August 2, 1948, the banker’s son and the factory director’s daughter were married: Gerd, son of Gertie née Oechelhäuser and Hans Kippenberger, and Dr. med. Eleonore “Lorchen” Augusta Elena, daughter of Otto and stepdaughter of his new, third wife Dr. med. Lore Leverkus. Despite taking place in the lean postwar years, it was “a real peacetime wedding,” thanks to various bartered items (coal for wine, for example), care packages, cured meats from the black market, and ration cards contributed by all the guests. There had been several small engagement parties rather than one big party, and now the wedding itself was celebrated in style for three days: guests marched through the village singing miners’ songs on the first night, carousing until nine the next morning; the written schedule for the second day said “Sleep late!”; finally came the ceremonies on the third day, first at the registry office and then in the church. After lunch on the third day, according to the program: “Catch your breath,” then coffee, and finally dancing.

Lore Leverkus and Gerd Kippenberger (in miner’s tunic) on their wedding day, 1948

© Kippenberger Family

The groom himself had illustrated the “wedding newspaper” that was handed out to all the guests, and had written most of the poems in it as well. Like so many other family occasions to come, this festive day was recorded for posterity: “Mother-in-law Lore greeted the guests at the front door in her slip. Father-in-law Abba stood in the bedroom in his long underwear, unashamed, while Little Mouse had a wreath pinned up in her hair. Meanwhile little female cousins of every shape and size shuttled back and forth through the house, being either fed or put to work. The sexton didn’t want to let us into the church until we paid the marriage fee.”

Their honeymoon was in the Bergisches Land: hiking in the mountains. He shoved rocks he found geologically interesting into her backpack, and she secretly took them out again and dropped them. Almost as soon as they got home—by boat to Düsseldorf and from there by streetcar—he was off again, for a month in England with his fellow students. She had a job by then with a country doctor, near Aachen, and she supported her husband while he was in school.

DAD

He was born on March 1, 1921, the oldest of four brothers, so in 1939 he had just graduated high school and finished his time in the national labor service. He began his hands-on training in the mines: “I had chosen the career of the old Siegerland families: coal miner. But then, of course, came the war.”

Later, when he would tell stories about the war years, they were almost always comic. He was determined to see the beautiful side of things and refused to let even a war quash his worldview. His memoirs of the time read like stories of adventure tourism: when he transferred in Berlin on the way to Poland as an eighteen-year-old soldier, for example, he felt “a tingly sensation from being abroad, not knowing what to expect.” In Poland, he went to bars and enthused about the Masurian lake country; in France, he visited Joan of Arc’s birthplace, flirted with a little French girl from Dijon, came to love Camembert, climbed the church tower in Amiens, and held hands with a girl named Adrienne in Nahours, drinking a glass of wine with her father. He named his horse in Pommern “Quo Vadis” and used him to reenact scenes from Karl May, the beloved German writer of American-style Western novels. In Russia he jumped naked into the icy water. Then things got unpleasant. “We woke up from the dream of playing at war into the reality. Commands, orders, standstills, eyes left, eyes right, dismissed.”

The CV that he later wrote up for an exhibition makes it sound as though the only thing he did during the whole war was art: diary sketches, landscape pictures, illustrations; invented scenes, real events, horses, people, caricatures, village idylls, Hungarian scenes, transferring ordnance maps onto three-dimensional sand-table models, and whittling with a pocketknife while a prisoner between May and July 1945.

He would later write to his young fiancée that he was rarely in a bad mood. “My recipe for the war is: whistle a tune whenever you get sad.” He must have had a lot of opportunities to whistle. There was a period when no one wanted to be in the same regiment as him because he was always the only surviving soldier from his last regiment.

He never spoke of the horrors—only dreamed about them. Well into the 1950s he would scream in his sleep at night, according to our mother. Later, in a letter to us children, he would write that he was not allowed to yell at the guys in the mine, even when he got angry at them: “If I did, they’d report me for rudeness, which they call bad personnel management now and really frown on. Nowadays they want only good personnel management. I can understand that—good personnel management is actually a beautiful thing. When I was still a soldier, I always craved some decent personnel management, but it wasn’t in fashion at the time. On the contrary. We had to yell and scream if we wanted to impress our superiors—whoever screamed the loudest was automatically the best. You can see from this how attitudes change over time.”

After a few months in an American prisoner-of-war camp, he returned home and started to study mining in Aachen. It was a booming industry after the war: the mines smoked and reeked, and “everyone was clamoring for coal,” as he wrote in 1950. The miners were the heroes of the postwar period—they provided warmth for the freezing Germans—and they were thanked with the annual Ruhr theater festival in Recklinghausen. Our parents would see many plays there over the years.

It was backbreaking work under ground: dirty, hot, and dangerous. “The mine shaft is the dairy cow of the place,” he wrote about his first workplace in Altenbögge, “except that it’s sometimes not quite as docile.” He would often experience just how hard it was to control this wild cow. “Sometimes I feel like the annoyances never stop.” There were explosions in the pit, or water would flood in; he often had to spend all night in the mine. But the worst was bringing dead bodies up out of the pit. He attended many funerals. Once, when Martin wrote from boarding school for our father’s birthday, he wished him three cheers: “once for luck in the mine, once for a very happy day, and third, most important, that you stay healthy.”

“The Mine,” Gerd Kippenberger

© Gerd Kippenberger

Still, maybe because of the danger, he found the work fascinating. “It’s important to be possessed in a way by your job.” Our father, as a young man, discovered in mining “all the oppositions and dualities of life itself”: cruelty and solidarity, friendship and backstabbing, crudity and humor, tradition and innovation. At a time when the Ruhr region was officially ashamed of being the Ruhr (it would later call itself “Rustia,” punning on “Russia,” in a self-deprecating publicity campaign that was heavily criticized), he saw the beauty in the ugliness: the austerity of the industrial architecture, the coexistence of shafthead frames and meadows, and especially the people—the workers’ direct and natural ways, their warmth and humor and pride. In the Ruhr region, he would later write, he, the Siegerlander, found his second homeland.

He had barely started his first job, in Dortmund, when our oldest sister, Babs, was born: July 28, 1950. “Barbara” was what most miners named their firstborn daughters, after their patron saint.

Mining turned out to be a feudal world. “We live on Mine Street, the royal road of Altenbögge, so to speak,” our father recorded. “The senior officials—the highest caste in the place—live there, so we are only tolerated and suffered.” But soon he himself belonged to that highest caste: he was made director of the Katharina Elisabeth Mine in Essen-Frillendorf in 1958 and given a giant house as a residence, with a huge garden, tended by gardeners. Sometimes our father had a chauffeur, Uncle Duvendach, who took trips with us.

But no sooner had he arrived in Essen than the great crisis in the mining industry began, as did worrying, anxiety, and fear for his job. “Now we need to get tough,” he wrote in September 1963 to friends in Munich. “The coal crisis continues, and whoever doesn’t go along (with the crisis) gets fired. Whoever fires the most people is the champion marksman.” His mine was shut down too; he was transferred to a desk job and eventually let go. In September 1972, just back from vacation, he got the news: “early retirement,” at fifty-one. A few months later, just days before Christmas, he had a heart attack. Only after several frustrating attempts to secure a foothold in the construction industry—likewise in crisis—did he find another position: as a manager at a plastic tubing company in Mülheim.

His fascination with mining and its traditions only grew in this period. He continued to do research, reading books on mining’s history and practice in other countries. When he died, he was buried in his miner’s tunic, meant for special occasions—the same one he had married our mother in.

He could be crude as well as charming and tended to find the shortest path from one social blunder to the next. He loved provocation and making fun of people. Once, introducing our sister Bine’s boyfriend—a mining engineer like him—to some colleagues in Aachen, he did not say the young man’s name, which he had probably already forgotten. He said, “Here’s the kid who wants to be my son-in-law.” It was a test, and Andreas passed it. Our father said what he thought, loud and clear, and also what he knew: for example, that there were safety problems down in the mine because the wooden supports for the shaft, from a company executive’s forest, were rotten. That got him into a lot of trouble. Still, he didn’t go as far as his son would later; he also paid court to his superiors. As he wrote to our mother once: “I think Mrs. Wussow [a friend] is right after all: I’m a revolutionary, but only in secret—someone who never makes the move.”

He was an exotic species in a conservative world, along with his whole family and their lifestyle. A “rare bird,” as they say. Our parents’ friend Ulla Hurck said that “he made the sober mining folks uneasy—he was a shock for them.” In a children’s story that he wrote for us, where he is recognizably the father, he is the only one not to laugh at the child who wanted a skating rink in the middle of summer. “He knew how much it hurt to be laughed at.”

“Diagram,” Gerd Kippenberger, 1965

© Gerd Kippenberger

“If he had not been the company director at the Katharina Mines, he would certainly have been a painter,” a newspaper wrote in an article about our father’s exhibition at the House of the Open Door in Frillendorf in 1960, one of the many exhibitions that he organized himself as a member of the artists’ society. He showed landscapes and city views, and his art, according to the newspaper critic, was “a beautiful, free expression of modern creativity.”

He usually painted on vacation and signed his pictures “kip.” But he didn’t need a canvas to make art. In the 1960s, the era of Pop Art, he made constructions from flotsam and jetsam he found on the beach, painted picture books for his grandchildren, built brightly colored wooden cities, and threw parties. He laid out gardens, first in Frillendorf and then, in his second life (for there would be another wife and more children), in Marl. There he bought an allotment, where he built hills, a frog pond, and a trellis for grapevines. He planted blackberries, raspberries, and blueberries. He named the path that the bushes were on “Blackcurrant Way” and placed his wooden figures everywhere as a special kind of scarecrow: The Passionate Lover, The Blue Angel, St. Francis of Assisi, The Market Lady with Sagging Breasts.

He wrote books about his travels, our house, the neighbors, parties, the Siegerland area, and his early years. The worse the crisis in the mining industry became, the more he clung to his private life. The stories were not invented, but he did fictionalize the truth, exaggerating, distorting, and embellishing. His brother called him a “magical realist.” The world was a stage in his books, and life was a play, or more specifically, a farce, with everything more comic than it actually was. He referred to himself in the third person, as “Father”; his wife was “Mother.” In one of his little books, Hike, 1963, about a walk he took with our mother and the two oldest children, he gave the “cast” at the beginning and ended with “The End.” He was everything in this theater—director, writer, star, and cameraman—except the audience. The camera was always there. Whenever we left the house, he hung the “photey” around his neck and over a belly that slowly grew fatter with the postwar economic recovery. He had no interest in taking snapshots, though—he directed us: behind this window, on that bridge, between those columns. We sisters hated it, but Martin loved it. He later turned one of these photos, where we’re standing with raised arms on the front steps of our great-grandparents’ little manor house, into a work of art, a postcard with the title “Hey, hey, hey, here are the Monkeys.”

On the front steps of our great-grandparents’ manor house in Siegen-Weidenau: Martin, Barbara, Sabine, Susanne, Bettina (bottom to top). Photo by our father, which Martin turn into a postcard in 1985: “Hey, hey, hey, here are the Monkeys.”

© Gerd Kippenberger/Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Every big party was planned from beginning to end, with a written program. The guests had to sing on cue. Since his first talk as a student, he had loved to give speeches entirely improvised—“I talked myself into such a state that everyone there listened, entranced.” He did not need a podium to be seen, of course, or a microphone to be heard: like all the men in his family, he had an impressive voice. It grew even stronger as he became hard of hearing, like many men in his profession—it often got so loud down in the mine that you had to scream to be heard.

To make completely sure that he would get speeches for his own birthday, he assigned them himself, along with suggested topics. Our instructions, printed in the invitation, were “Our father as he really is. Only my four daughters are qualified to speak, and they are requested to please agree on the content beforehand and on who should deliver the address.” The only one of his children who could have performed the task without any difficulty was Martin, but he was in Brazil at the time. Our protests meant nothing to him—he just threatened to write the speech himself. So he got what he wanted: our father as he really was.

Afterward his cousin came up to us with a serious face and a sepulchral voice: someday we would be sorry we had given such a speech. But our father—who knew he had skin cancer and not long to live—had enjoyed himself immensely.

Not even at the very end, after seven years of fierce struggle against the cancer that finally defeated him, did he give up the reins. Our father staged his own funeral. In the weeks before his death, when he could barely hold a pen any more and his handwriting was growing more and more shaky, he wrote out his stage directions: whom we should invite (and whom we should not); where the funeral meal should under no circumstances take place; that a bagpiper should play; that he should lie in state in his miner’s tunic; and that his coffin should have eight handles, one for each child and stepchild. He got everything he wanted, and speeches to his taste, too.

Indecisiveness irritated him. “I’m not the type to hesitate for a long time,” he wrote as a young man, before he was our father. Once, when he heard that his semester would begin later than expected, he got on the next train, stayed with his grandmother in Siegen, and rode from one mine to the next, meeting geologists and getting new ideas. When our mother once again didn’t order anything to drink at a restaurant in Munich, our father later wrote, “Either she wasn’t thirsty, or she was thirsty but didn’t know what to do about it.” Both possibilities were equally incomprehensible to him. He liked to drink—beer, wine, liquor—this last with the guys from the mine, usually. He sometimes came home a little drunk and smelling of cigarette smoke.

Even though he was an engineer, he understood nothing about technology in everyday life. Maybe he didn’t want to understand. Whenever something needed fixing, the clever neighbors had to help out; when they weren’t around—if the camera broke on vacation or the film projector wasn’t working on Christmas—a major marital crisis ensued. He lacked both the calm and the patience to fix things. When it was time for us to set out, whether for the day or for six weeks, he got in the car and leaned on the horn, and everyone had to be ready. It didn’t matter that our mother still had meals to pack, shoelaces to tie, diapers to change, or suitcases to shut—when he was determined, he was determined, and he charged ahead deaf and blind, as he himself said, unwilling to even hear whatever the various members of the family wanted or were whining about. Otherwise, he knew he would never reach his goal. And he wanted to.

When he was diagnosed with skin cancer, he was determined to live, even if it meant having an operation every week. He managed a few years more than the doctors and the statistics had allotted him. “Onward and upward!” he scribbled in a shaky hand six months before his death, adding a stick figure climbing up a flight of stairs and sinking into an armchair. He was held up as a model patient in the hospital and even gave a lecture about how to do it: how to live your life anyway.

He always moved forward, never backward, except in his memories, which were as important to him as new experiences. He preserved these memories in little books, usually illustrated and always self-published—memories of his mother, whose name he bore (she was Gertie); of his childhood, his hometown, family celebrations; of Pastor Noa, who took his own life under the Nazis. He made the most beautiful of his books out of several hundred family letters. It’s not that he lived in the past, but that for him the past was the foundation of everything that came in the present. “Remember,” he told me to give me courage the night before my university exams, “you’re a Kippenberger!” He meant it not as a threat or a warning, but casually and naturally: nothing bad can happen to one of us! He was as proud to be a Kippenberger as he was to be a pigheaded Siegerlander, or a miner, or a father of five (and later eight) children. “One Family One Line,” Martin inscribed on our father’s gravestone. This is the attitude we grew up with.

Always forward, no backtracking: that was the ironclad rule of all our walks and travels. Never walk the same road twice. On the way back, we had to seek out another path, no matter how complicated or hard it was to find, or whether we would get lost. He always ran ahead, even on vacation. How was he supposed to notice when our mother clumsily stumbled and fell in Barcelona? “The husband, three steps ahead as usual, didn’t even turn around.” Courteous Spaniards helped her to her feet.

He rarely found downtime, as he put it, for reading—sometimes a thriller, but usually not even that. “You called it restlessness in my blood,” he wrote our mother once. She was someone who, wherever she went, looked for a place to sit and read a book, while his gaze was always directed out at the landscape or the sunset. “There’s probably some truth in that. Maybe I’m only running away from myself. Sometimes life is only a kind of running away, after all.”

He enjoyed life, and he loved to eat—preferably big, hearty meals. Every Saturday at our house there was thick, rich soup—split pea, lentil, vegetable—because he liked it so much. After his in-laws served him half a piece of meat and counted out the potatoes for lunch, he avoided going back. He also liked to cook, for guests and on weekends, on vacation and out camping. He cooked the same way he painted: improvising, without recipes and definitely not measuring cups. And as with his painting, writing, and celebrating, it had to be big. For him, cooking was also art, though not a pure art for art’s sake—the important thing was the eating, in as large a group as possible, along with wine and conversation.

“Father Kip: Leader of the Family. Mother Kip: His wife and mother of five children.” So ran their descriptions in the dramatis personae of his book Hike, 1963. Day-to-day matters and child rearing were her responsibility. During their years in Essen he left the house at seven in the morning, came home for lunch, lay down for fifteen minutes (during which there had to be absolute silence in the house), then drank an enormous cup of tea (he allowed himself coffee only on vacation: “it gets me too excited”) and left until seven at night.

He was responsible for weekends, and sunshine. Monday through Friday our mother hauled groceries home from the co-op in two giant bags, food for a large family plus guests and the help. On Saturday our father went to the market, chitchatted with the market women, tasted the cheese, bought too much of everything (and not necessarily what we needed), and was our maître de plaisir for the rest of the weekend. On Sunday our mother often lay in bed with a migraine, and was finally left in peace while the rest of us took a day trip.

He was constantly getting ideas. That’s when our mother got scared. Ideas meant that he would suddenly turn everything upside down, redecorate the house, maybe buy some exotic birds. Just three years after we moved into the house in Essen, when our mother had taken us children away on vacation, he wrote to her that he had “girded his loins and decided to thoroughly change some things in our house (no half measures). First the dining room. Out with the piano. We found a good place for it in the large children’s room (everything with Heia’s agreement). The other junk is being spread around the house too. Now the furniture will stand clean and pure in the pared-down room. Some of the pictures were already taken down off the walls—now the rest. Everything has to be rethought from its foundations.”

He had found new lighting for the dining room, “five simple, clear plastic tubes in a row to emphasize the length of the table and the shape of the room.” Plus it was finally bright enough: “I can’t stand this gloom any longer.” He was looking for a carpet to tie the room together: “Colorful, but strictly vertical stripes to emphasize the lines, you know, not scitter-scatter everywhere,” he told the carpet dealer.

Maybe his family was another of his “ideas.” He liked the family best when it was gathered around a long table, as multitudinous and loud as possible. He sat at the head of the table, of course. We called him “Papa,” but he usually signed his letters “Your Father.” And then he retreated. First he would go to the wooden loft, two comfortable rooms, that he had built above the garage in the garden and named “Father’s Peace.” Soon he started sleeping there, too. Then he slipped even farther away, to the apartment in Marl that our mother had bought for them to share in their old age. He seemed to grow younger: he let his muttonchops and beard grow long, adopted a Caesar haircut, traded in his old Opel Captain (the biggest family sedan available at the time) for a small, sporty Opel two-door, and took a vacation, alone for the first time, to Greece, to try to find himself among the men’s-only monasteries.

He had, as he put it himself, a weakness for the romantic. And for women. As was already printed in their wedding newspaper, “From Siegerlan’ / He’s a ladies man / And whoever sees him can understand / He’s someone no girl can withstand! / When Gerd rolls his rrrr ’s all full of charm / Even the coldest heart gets warm.”

He met Petra Biggemann in 1968, at a union dance, and married her in 1971. She already had two young sons, Jochen and Claus, and a third arrived in 1973: Moritz. When he told Martin the news, Martin immediately asked to be named the godfather. And he was.

MOM

Born February 11, 1922, she was an Aquarius and so, in her words, prone to creative flights of fancy but without a trace of ambition. And incapable of logical thought: “The Aquarius thinks in zigzags.”

She studied medicine during the war, in Frankfurt, Freiburg, and Göttingen. During vacations she had to perform her national labor service, first in a factory and later in a military hospital. Our parents were barely engaged when she started imagining their future life with children, calling him “Pappes,” and enthusing about the little Hansie and little Conrad they were going to have soon. “It can be a Barbara, too,” he would throw in. She didn’t want one child—she wanted lots of children. She couldn’t wait to be a mother.

She was eight years old when her mother, Paula Leverkus, died at thirty-four. Paula had helped take care of her husband’s factory workers as a nurse and had caught tuberculosis. Our mother had nothing except a few vague memories of her, a few photographs and letters; she didn’t miss her mother, she would later say, since she never knew what it was like to have one.

She was not like other mothers. She couldn’t cook, except spaghetti and noodle casseroles. She never buttered our toast. We had to pack our own knapsacks, and when we fell she would just tell us, “Go put some iodine on it.” She was definitely not one of those mothers who constantly wipe their children’s snotty noses and pull up their socks. Our underwear peeked out from under our clothes. She never fretted when we started to go off on our own, and we never had to call home to say we had arrived safely; she knew we would. Bad news, she liked to say, comes anyway, and soon enough. Her child rearing methods were laissez-faire, although she could be strict and sometimes even a bit hysterical. All three of them were drama queens: father, mother, and son.

Lore Kippenberger in the mid-1970s

© Kippenberger Family

Giving presents was her passion; organization was not her strong suit. She was constantly looking for her glasses, or buying Christmas presents in summer and hiding them so well that she never found them again. Cleaning was a nightmare for her and when, after a long vacation, she finally had to do it, she gave us a few coins, if we were lucky, and sent us off to the vending machines so that she could take out her bad mood on the vacuum cleaner instead of on us. In day-to-day life, keeping house oppressed her: we didn’t help out enough and were too messy. “If I was your cleaning lady, I would have given notice a long time ago,” she said once.

She liked to quote the English saying “My house is clean enough to be healthy and dirty enough to be happy.” For one thing, she felt that cleaning—even more than cooking—was a thankless task, the results of which were obliterated swiftly and unremarked, as though it had never happened. Secondly, she felt that “maintaining cleanliness and order, if you put too much time and care into it, works against the peace and happiness of the household.” So she did what absolutely had to be done, and that was more than enough. Even the laundry, which she had to haul out to dry in the yard or on the roof, would have been enough, but then there was also shopping, helping with homework, and battling our teachers.

In the only year when all five of us children passed all of our classes and moved up a grade, our father gave her a large brooch with our names on the back as a “Maternal Order of Moving Grades.” He knew she had earned it. “Tell me the truth,” she said to her friend Christel Hassis once, “are we all actually idiots, since our children do so badly? I always thought we were the crème de la crème .”

She gave us names with an eye to our future, names that could be pronounced easily in other languages and which would go well with titles of nobility. That said, she didn’t raise her daughters just to get married—we should have careers first. And driver’s licenses (the only one of her children who never got one was Martin). She cared more that her first son-in-law, Lars, was “a nice boy” than whether or not he had a successful career.

She wore her hair permed—sometimes even wigs, when there wasn’t enough time for visits to the hairdresser—and never left the house without lipstick and pearls. Not real pearls, of course, and she especially liked that they were fake. Thanks to her high-class background and way of carrying herself, she thought, no one would ever suspect it.

After bearing five children, she had lost her slender figure and was constantly on a diet. She liked to moan and groan that she had only to eat half a praline to gain three pounds. In fact, she had probably eaten half the box, after a day of starving herself. She usually wore big dresses, brightly colored and patterned; Marimekko was her favorite brand. Her glasses and rings were large, too, and later so were her hats. Only her shoes were flat and practical.

She could lie and read in bed for hours, or in the sun on the beach for weeks. On the bookshelves was literature that hadn’t been available under the Nazis, in the early series of inexpensive paperbacks published by rororo : Fallada, Hemingway, C. W. Ceram, Carson McCullers, Truman Capote, Harper Lee, Roald Dahl, Siegfried Lenz, Christa Wolf, Marie Luise Kaschnitz. She devoured them. When she was finished, the book would be loaned to a friend, with a letter full of commentary. She was a critical reader: not even Goethe and Schiller were safe: “Schiller’s Don Carlos is also utterly out-of-date. . . . What bombastic nonsense!” She started an imaginary correspondence with Goethe, among other things suggesting improvements to certain lines of verse that, in her opinion, fell short of the mark.

Then her husband met Petra Biggemann and her marriage fell apart. She died her first death then, she told a friend, and mourned the love of her life. The big, loud house soon grew even quiet and emptier: Tina left to become a midwife, and Martin spent more time in bars than at home.

For decades her main occupation had been wife and mother, and now she was a divorcée. A rarity in the late sixties, especially in her circle: I was the only child in my class whose parents were divorced. She was forced to face the fact that the society she lived in was a kind of Noah’s Ark: “Entrance permitted only in pairs!” Single women were not invited anywhere because they would ruin the even number of seats at the table.

She missed her old social life. Our sister Tina took a vacation to Wales once. Our mother had been to Wales too in her day. When Tina wrote home, she asked, “How many people did you meet here?! Everyone seems to know you.” People meant more to her than things, our father thought: “You can talk to people, you can write to them, they let you give them things when you have too much. The danger is just that you give away too much of yourself.” She made people laugh and made herself laugh, too, until tears ran down her face, especially with her female friends.

As a child she had been raised as her brothers’ equal. There was no question that she would go to a real academic high school, not some girls’ school home-ec nonsense. Thirty years later, she learned that the world was not as emancipated as she had thought. But she still had her family: she never broke off contact with her in-laws or with our father. She even took care of his new sons sometimes.

Then, twice, she almost really died. After a hysterectomy she had an embolism, and shortly afterward she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She took it with gallows humor, writing to Wiltrud Roser in high style, with an allusion to Schiller no less: “Grant me my wish to be your third confederate! On Tuesday I am having my right breast removed. Who would have thought! No longer full-bosomed—now half-bosomed. Warmest wishes, Your Lore.” On her New Year’s card, for which Martin drew an apocalyptic picture, she printed as a motto the Goethe quote “ Allen Gewalten zum Trozt sich erhalten” (Despite all the violent forces against us, we will overcome).

Despite everything, she flourished again in the years after her divorce. By the standards of the time, she was an old woman. When she was forty-two, the photographer in a Munich photo studio told her she had so many wrinkles that there was no point in retouching the photo; besides, it would be too expensive. Our mother put a big hat on her head and sailed out into the world. “The older my mother got,” Martin later said in an interview, “the more beautiful she became. She had no womb and no breasts left but grew more and more beautiful, free, and open. More open. She got so much older, and learned that she had cancer, and then suddenly: Pow! Everything opened up.... She would say, ‘Come on, kids, let’s go to Paris! And no squabbling about your inheritance!’”

Having left her career almost twenty years before, she started working again, as a doctor in the Gelsenkirchen public health department, and liked it very much. For years she had not driven a car—the husband was always in the driver’s seat back then—but now she bought herself a Citroen 2CV, a car that at the time was driven mostly by college students. Not that she shared all their views—free love didn’t interest her in the least, she categorically opposed the pill, and she often gave lectures condemning drugs after Martin started taking them. It was just that she liked the little Deux Chevaux, and it was cheap.

Change-of-address card: “Mother Kippage and Her Children” (MK, 1971)

© Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

What was left of the family moved out of the big house into a new duplex apartment she set up. Its great luxury: floorboard heating. No more cold feet ever again!

Martin drew the change-of-address card himself and called it “Mother Kippage and Her Children,” a reference to Brecht’s play Mother Courage and Her Children. He drew himself sprawled out in an armchair, grinning and exhausted, with long hair, and our mother in a large hat, smoking a cigarette. She had started smoking, or puffing, to be exact—she never inhaled her Lord Extras.

From our guestbook in Zandvoort, the Netherlands

© Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

“Money can’t buy happiness, but it sure makes the sadness easier,” she told a friend after she inherited money. Until then she had lived frugally, which was how she was raised and what she was used to from the war and the early postwar years. Nothing was ever thrown away, whether it was used wrapping paper, old food, or even moldy bread; as a teenager, she wore her long-dead mother’s clothes, retailored; her father wore the coats of his brother who had fallen in WWI. We children had to share everything too: clothes, knapsacks, first-day-of-school candies. Martin was lucky: as the only boy, he had lederhosen of his own. Our mother adored shopping, but, as our father wrote, “She could only get really excited about affordable things.”

Babs said, “It’s good to know that in the end she finally took taxis, stayed in good hotels, and wasn’t addicted to shopping only at clearance sales. Any extra money she took in was frittered away within the family, at the city’s better restaurants.” This extra income was from the “Prostitute Control Board,” where she filled in for a colleague. She loved it and soon knew all the women who came for checkups every week, including a grandmother. She liked talking to them, and then she again had stories to tell us. She certainly liked the prostitutes more than the teachers she had to deal with at the public health department.

Finally, she rediscovered her Spanish blood—allegedly slightly blue as well. She had always been proud of it and did in fact look slightly Latin: tall, with black hair and long, thin fingers. As early as 1954, the first time she crossed the Pyrenees, she no sooner caught sight of the customs officials than she fell under the spell of Spain’s beauty, and that of its men, especially the “bold and elegant” men who fought the bulls in the ring. She, who usually kept the peace by doing whatever our father wanted, could not get enough of the bullfight and her Spanish blood surged so powerfully that at the end of the fight she almost threw her purse into the ring like the Spanish women. Only her German frugality held her back. Of all her ancestors, her favorite was Don Antonio, a nobleman who, it was said, had been forced to immigrate to Venezuela after a duel. “He was an adventurer.” That was exactly why our mother loved him. “Everything that we possess of charm and generosity, our inborn kindness, that ‘certain something’—it all comes from Don Antonio,” she wrote. After the divorce she learned Spanish, in Malaga and at the Berlitz school in Essen; during breaks she would step out for a coffee and chat with the bums. When she traveled to Andalusia with Babs on a cheap package holiday, “she insisted on going to flamenco and bullfights and shouted Olé! with the Spaniards.” Martin drew her in this role once, dancing flamenco-style on the table, with OOLEE OOLEE next to her. It was New Year’s Eve, 1974.

By then she had long since had what Virginia Woolf wanted all women to have: a room of her own where she could write. After the war, she had traded her accordion for a typewriter, on which she would write her long letters. The mailman mattered more to her than the milkman.

Before long she was composing not only letters but humorous little articles, about, for example, “our beloved dust,” or Tupperware parties, “happenings,” visitors, teachers. Always, frugal as she was, on scrap paper: the back of junk mail, invitations, day planners, and discarded drafts. She wrote about the comic side of our life, for the Doctor’s Paper, the German Sunday Magazine, the Christian Friendly Encounter : “The words just flow from my pen, even if it’s all just mental masturbation.”

One evening in 1974, she appeared at an event of the National Association of Writer-Doctors in Göttingen. After a Beethoven performance, poems were recited, philosophical disquisitions held on “the significance of the pause,” and reflections aired on “solitude.” Then our mother came onstage to present her piece: “Daddy Dummy.” She knew that everything she experienced could be turned into a story, and that nothing was ever so bad that it couldn’t sound hilarious on paper later.

She liked that no one could boss her around. Once, at an event for the Social Democratic Party “on the position of women in the modern world,” when she expressed her own opinion and was then accused by a party member of being a traitor, she said, “That’s what I want to be. I’m neither ‘us’ nor ‘them,’ I want to say what I think.” She never wanted to subordinate herself to a party and its pragmatic electoral politics. “What’s the use of working and struggling to emancipate myself from a husband just to dance to other men’s tunes? They’re probably less intelligent than he was, and I don’t even love them enough to forgive them when they make me mad.”

All of which is not to say that she never sought others’ approval. Even her advisor’s praise of her dissertation made her happy: “What author would not be delighted at such a response to his or her first work?” She was livid when a story of hers wasn’t printed, and was proud when Brigitte, Germany’s largest women’s magazine, solicited a piece from her: “So now I’ve come far enough that they want something from me, not the other way around!”

Soon she started to dream of becoming famous. In 1968, having given herself the assignment to write a book that year, she traveled to Hamburg for the twentieth anniversary of the Lutheran Sunday Magazine, “to put myself out there.” She drank champagne to boost her spirits and fortify her self-confidence, and met accomplished writers like Ernst von Salomon and Isabella Nadolny. She made an impression, and not only because she was one of fifteen women among the two hundred guests: “I may not be so impressive by nature, and not a famous writer, but I put a wagon wheel of a hat on my head, and it worked like it always does.” A few hours later, she took the train back to reality: “At home I was met with the news that Sanni had thrown up, Bettina had fainted, and the boy had gotten into trouble.” Now she didn’t want any more children. “From now on I will give birth only artistically.”

She also wrote about her cancer, which caused quite an uproar. That wasn’t done at the time—you were supposed to “bear it stoically,” as the death notice would always say.

Like our father, she planned her own funeral: compiled an address list for the guests, warned us to get the cheapest coffin and not fall for any scams, since after all it would just be burned anyway, and asked to be decked with carnations, her favorite flower.

She was at the threshold of a new life phase. Her two youngest children were about to leave home—Bine was going to be a medical assistant in Munich and I was off to university in Tübingen—and she was dividing her duplex apartment to rent out a floor. The apartment was full of contractors when the call came: the accident happened during lunch hour, while our mother was coming home from the health department. In his book Café Central, Martin would write about how “his mother made the transition from living mother to dead mother (a truck overloaded with EuroPallets took a curve too fast and lost some of its freight, which caused my mother’s death) (so she didn’t have to die a slow and painful death of cancer).” She died a week later without regaining consciousness, in 1976, at age fifty-four. She was buried in Wiesbaden, where she was born, in the Leverkus family grave.

Essen-Frillendorf (Gerd Kippenberger);

bottom center: Number 86, our house

© Gerd Kippenberger

ESSEN-FRILLENDORF

We lived in Essen-Frillendorf. After our father was made director of the mine, he moved us from Dortmund into the heart of the Ruhr, right next to mines and brickworks, where we grew up among miners and laborers.

Our parents loved Anton the pitman and his curt sayings, and laughed at Jürgen von Manger, who didn’t even come from the Ruhr region (like them). The people’s warmth and humor, their self-confidence, ease, and readiness to help, shaped all of us. Here you didn’t make a big to-do, you just did what needed doing. People were strong characters, open and very direct, always ready to laugh at themselves. No one took themselves so terribly seriously. They drank beer, told stories, made fun of each other, and accepted people as they were, faults and all. They teased with affection.

The Kippenberger family (Reiner Zimnik, 1961)

© Reiner Zimnik

Frillendorf was a real village, with everything that entails: candy kiosk, cemetery, public primary school, village idiot, and church. But it was a village in the middle of the city, only three streetcar stops from the center of Essen. Farmer Schmidt had his farmstead right near us, and large fields lay alongside the streets.

A Mrs. Böhler watched over the entrance to the yard and the alley of chestnut trees that led to our house, which was at the end of a cul-de-sac. Mr. Böhler only ever appeared in the background, in his undershirt. She put her pillow in the window, rested her heavy breasts on it, and looked out at everyone, sending curses after them. There was hardly any television in those days—only three stations for a couple of hours a day—and what we had to offer was apparently more interesting to her. She shows up several times in Martin’s books.

“St. Nicholas at the Kippenberger’s’” (Reiner Zimnik, 1961)

© Reiner Zimnik

Our parents had moved often since the start of their marriage, several times in and around Dortmund during the previous few years. All five of us children were born in Dortmund and the apartments got bigger with the increasing number of children. But only now, in 1958, did they move into a house where they could really stretch out—a stage on which to perform their life. It was a paradise for us children. “A crazy house at the end of a cul-de-sac” is how the local newspaper described 86 Auf der Litten in an article about Martin when he showed his work for the first time, at eighteen years old. “The rooms and studios are stuffed full of pictures, posters, and objects. On the stairs, an outer-space hotel made of radiator parts that Martin’s father put together. The chaos is welcoming, clean, and cozy. And when the sunlight plays across the garden with its naive stone sculptures of horses and cowboys, it is almost possible to believe in an ideal world again.”

Or, as our mother once wrote, more soberly, “We lived in a huge house with countless rooms and just as many side rooms, nooks, and crannies. It was a nightmare for cleaning ladies—almost every time a candidate interviewed, she turned around and left. A paradise, but with its flaws: it never warmed up past sixty-three degrees, because the old heating system couldn’t manage anything higher; mice would run around in the bedrooms every now and then.”

The Kippenbergers in Essen-Frillendorf, 1961: Bettina, Martin, Susanne, Lore, Barbara, Gerd, Sabine (l. to r.)

© Ilse Pässler

There were always children running around, with bows untied and underpants slipping down—no one watched or tended them when they were playing. Life consisted of homework and playing and nothing else: no hockey practice, no saxophone lessons, no carriage rides through the city. There were a good dozen other children besides us who were always there in the yard to play. It was a life lived in public, in company. You didn’t retreat into your room when you wanted to play; you went outside.

Or else to the Kinderhaus , or kids’ house. They redid the old laundry shed in the garden for us, and for the grown-ups to use for holiday celebrations. In fact, in our family everybody had their own house: the ducks, the chickens, the pigeons, our father, and Martin, too. There was a wooden hut, the “Martin hermitage,” tucked away in a little woods connected to the garden, but he rarely used it. What would he want with an isolated hut in the woods? He was never a recluse. He wanted to be with other people.

Behind our Kinderhaus was a playground with a slide, merry-go-round, swing, sandbox, and seesaw—all from a miners’ kindergarten that had just closed. The mining crisis had already begun, and the feudal world was crumbling around us. A big slate blackboard hung on the fence, with a tree trunk in front of it as a bench—that was the school. We could sit behind the wheel of an old, brightly painted BMW and play driving. We used the nearby brickworks as a kiln for our little clay bowls and figurines. We could play croquet on the grass, hopscotch and double Dutch on the sidewalks. There was a big suitcase in the attic with costumes for dressing up.

The gigantic garden, as big as a park and surrounded by huge old trees and two little wild forests, was there to enjoy. Everything practical—vegetable garden, greenhouse—our father tore down and then started to rebuild. So the garden filled up with bushes and trees, lilacs, goldenrain, tree of heaven, roses and sumacs, classical columns and billboard posts, a flagpole, a bathtub for cooling the drinks at parties and then the guests. More and more sculptures populated the garden: Genevieve the Pretty and others of less classical beauty—a cowboy and horse, and a hunter with dachshund, made by a retired miner who caused a sensation as an outsider artist. There was a large terrace, where later the Hollywood swing stood, and next to the old weeping willow was a lake where the ducks swam.

Other people had dogs and cats. If it were up to our mother, we would have had no animals at all—she didn’t care about them, and they made extra work for her when she had more than enough to do. But since it was up to our father—who at least knew enough not to buy monkeys; if he had, our mother threatened, she would leave him—we did have animals: bantam chickens, goldfish, turtles, and two ducks, Angelina and Antonius. Nobody in the family, our mother wrote, had any more of a clue about animals than she did, but “in place of actual knowledge they substituted enthusiasm. The consequence for the turtles was a rapid death.” The exotic birds that our father bought all quickly died off, too. The only animal tough enough to survive in our family was Little Hans, the canary.

“The Kippenberger Children’s Carnival,” with our father as clown

(Reiner Zimnik, 1961) © Reiner Zimnik

Our house was always full of children, full of pictures, full of visitors. You were never alone. “House others happily” was the pastor’s parting advice for our parents at their wedding, but they would have done so anyway. A year later, in Aachen, they had cards printed up with our father’s drawings to use for inviting guests. In Frillendorf, the door was always open: whoever came, invited or not, was welcome to sit down and join in.

There were nannies and au pairs, live-in maids and men who helped around the house (or didn’t). Friends’ and relatives’ sons and daughters who needed a place to stay while at school or in a residency lived with us; so did various children stranded in Frillendorf. Petra Lützkendorf, the artist, brought her son Pippus to stay with us for a couple of weeks. The “Belgian fleas” spent their holidays there too: two siblings, a brother and sister, whose mother was in a psychiatric ward and whose professor father had his head in the clouds, so they were left to hop and leap over our tables, benches, and armoires at will, grabbing onto anything and everything. Pedro, the fat waiter from Martin’s regular bar, lived under our roof for a while, too, since he had no place of his own. For a long while, in fact, until our mother finally threw him out.

Sigga came to stay with us from Iceland, Chantal from Belgium, and Genevieve from French Switzerland. Carolyn came from Wales for what should have been a couple of weeks, but she stayed a whole year. She was short and fat and uncomplicated, and the family chaos didn’t bother her at all. We all loved Carolyn and later went to visit her in Ffestiniog; Martin stayed with her a few times.

“Easter with the Kippenbergers” (Reiner Zimnik, 1961)

© Reiner Zimnik

Pelle, the student from Norway who wanted to work for a couple of weeks in Essen, was our mother’s favorite. Dear, cheerful Pelle, who was training for the Olympics.

They all came and went. Only Heia and Köckel were always there: our neighbors. Without them we would have sunk into chaos, and our lives would not have functioned. Köckel fired up the old coal heater in the basement every morning and helped out whenever anything needed fixing. Energetic Heia kept things running smoothly, looked after the little ones, and kept her cool, even when her hand got caught in the blender. She roasted the meatballs and fried the potato pancakes that our mother didn’t know how to cook for us, and that we used for eating contests (Bine won: she ate twelve). The kitchen was our favorite place, because, among other reasons, it was the only warm room in the whole huge house. We ate there, talked there, drew, fought, baked cookies, and did our homework, and Martin monkeyed around and imitated people.

Our father called us “the Piranha family”: wherever there was something to eat, we threw ourselves at it, afraid that otherwise we would find nothing left. There were never enough treats; actually, there were sweets only when visitors brought them. But with seven family members, houseguests, and grandparents, it was almost always someone’s birthday: the only day in the year when the child was in charge of who was invited, what game to play, and what food to eat. Other holidays we celebrated included Father’s Day, Mother’s Day, Children’s Day (which our parents had introduced specially for us), the Mother-Isn’t-Home Party, Confirmation Day (in “special house style”), May Day, and Summer.

“St. Martin’s Day Procession at the Kippenbergers’” (Reiner Zimnik, 1961)

© Reiner Zimnik

Our parents were in their element as hosts: relaxed, happy, and generous. And they enjoyed themselves at least as much as their guests. “They didn’t go around serving their guests,” one cousin said. “They were ahead of their time that way.” They just put a big pot of soup on the stove for people to serve themselves, and a hundred eggs next to the stove for them to cook on their own. After a meal our mother sometimes even pressed aprons into the hands of the astonished men so that they would help with the dishes.

On December 6, St. Nicholas came to our house in person in his fur hat and loden coat and with his golden book. For advent it was the trombone choir, and at Christmas we hosted our whole extended family, who came back again for Easter. Several hundred eggs would be painted, Father would haul them into the garden by the bucketful, and many of them would be found only weeks later, or never.

Every year there were two Carnivals, one for the children and one for the grownups. Our parents would dress as Caesar and Cleopatra, or Zeus and Helen of Troy; our mother especially liked dressing up in slutty costumes: “cheap and trashy with all my heart.” “They kissed each other, loved each other, stayed in love, tragedies ensued,” our father wrote. “It took three years before some people surmounted the moral crisis of our first Carnival celebration in Aachen.” There was often a theme for the party, usually from a play or movie: “Greek Seeking Greekess,” “Suzie Wong,” “Guys and Dolls.”

Even for the summer party, people dressed in costume and danced until dawn. The massive buffet was set up on a market stall—pickled eggs, cucumbers, peasant bread—and we children got to drink whatever was left in all the opened cola bottles the next morning. Every party was planned, with things to watch and things to do, from a polonaise to a pantomime show to a ride in a donkey cart. “We will expect you at 4 p.m. and assume you will stay late,” read the invitation to the advent party of 1962, where more than a hundred guests spread out through the whole house and into the side houses, too, to “make, glue, decorate, bake, paint, dress, arrange, and photograph” under the direction of the master and mistress of the house, artists, and other friends. The church trombone choir appeared on the stairs. Guests were asked not to come empty-handed: “We also plan to collect clothes, toys, groceries, etc. for the elderly and needy in our community and for packages to send to the East.”

Our mother said once, “No one should ever say they don’t have time for Christmas preparations. I would say that they don’t have the heart, or the imagination.” For weeks leading up to the holiday, presents were wrapped, cookies baked, gifts put together; on the day after Christmas our mother would lie in bed, sick with exhaustion. “You love to overdo it,” our father told her. “Conserving your energy is not your strong suit.”

By New Year’s, everybody was worn out—except our father and Martin. Our father tried his best to keep us up, he wrote, but “Mother always gets tired and then there’s nothing to be done. Father is offended that no one appreciates his fireworks. Everyone’s yawning or snoring.” Only Martin went along with him to the neighbors next door, “since he likes dancing so much, and he’s right, it’s fun.”

Even when they were away from home our parents threw parties, for example in Munich at the house of our uncle Hanns, the youngest of our father’s three brothers. “Five Minutes Each” was the name of this party: only artist friends were invited, and “everyone is allowed to put on their own show, if they want, and if they don’t want to, they don’t have to.” One couple played guitars, a poet read, a sculptor brought out his sculptures, an illustrator told stories. The rest danced or contented themselves with being the audience.

The parties were always raucous, even when only the family members were there. In fact, those were often the loudest. No one went around on eggshells at the Kippenbergers’. “Uncle Otto made fun of Uncle Albrecht and father defended him. Then Leo was teased and Albrecht started defending him. In any case, it was all very lively.” Too lively for some people. At one legendary Christmas party, when the whole extended family had come over for turkey (three turkeys, to be precise), one uncle’s posh fiancée left the house in tears after a dirty joke and never returned to her intended again. Every party was a test of fortitude.

On weekends, we usually took day trips. We were dragged everywhere, to exhibitions, to Castle Benrath, to the Weseler Forest, and to the Münster area, with its moated castles and the poet Annette von Droste-Hülshoff’s Rüschhaus, which we visited again and again. Martin sought her out again later; for his 1997 sculpture exhibition, he set up a subway entrance next to the poet’s sculpture.

Every year on St. Martin’s Day, November 11, we traveled to Cappenberg to visit the Jansens, who also had five children. They had a big house with a fireplace and a dollhouse, and there was a lamplit procession with a real St. Martin on a real horse, which our Martin was allowed to ride, too. He was so proud of his namesake and this privilege that he was happy to share his bag of candy later. On All Saints Day we were allowed to go to the carnival in Soest with the Jansens: first came pea soup with the Sachses, then everyone got a roll of coins and could go crazy with it, and when we got lost we would be whistled back with the special family code-melody.

Trip to the Drachenfels: Father, Sabine, Susanne, Martin, Pippus (son of the artist Petra Lützkendorf), Mother, and two au pairs (l. to r.)

© Kippenberger Family

On Pentecost we went to Siegen, to the little manor house where our gay great-uncle lived with his Silesian housekeeper; in early summer, it was off to Drachenfels, where the first thing we did was have our picture taken in a photography studio—draped on and around a donkey, or behind a cardboard cutout of an airplane, with our arms hanging loose over the side. We children had never been on a real plane. Then it was time for a donkey ride or a hike on foot up the mountain, where we stopped into a hiker’s restaurant and were shoved into a corner, since families with lots of children were considered antisocial at the time.

All of our activities and celebrations were recorded—in pictures, home movies, photos, and words—by our mother, our father, and our artist friends. Petra Haselhorst-Lützkendorf, Karin Walther, Ernst and Annemarie Graupner, Elisabeth and Bernhard Kraus, Reiner Zimnik, Luis Delefant, Wiltrud Roser and her sister Hildegund von Debschitz, Janosch, and so on. Our life was turned into art. We were embroidered, painted, sewn, woven—all hanging on our own walls. It wasn’t a matter of good likenesses, only of the idea: like Wiltrud Roser, many of the artists didn’t know us in person at all when they received the assignment.

Polonaise at a summer party on the Frillendorf lawn

© Kippenberger Family

We look beautiful, harmonious, and cheerful in all of these family pictures except one: the large group portrait painted by Ilse Häfner-Mode, a small, lively woman with a pageboy haircut and a pipe in her mouth. We had to spend hours in her Düsseldorf studio—as tiny a room as she was a person, though it nevertheless also served as her apartment—sitting and standing as her models with the puppets and figurines that populated her house. We never looked so sad in our lives. The painting is as melancholy as all her other pictures. She was an expressionist who had studied in Berlin in the twenties, and a Jewish woman who had been in a concentration camp, but that was never spoken of, only whispered. Later, after our mother’s death, there was never any conflict between us siblings about our inheritance except over this one piece: Martin, who had been sent to study painting with her as a boy, absolutely wanted it at all costs.

Contemporary art wasn’t something our parents bought anonymously from unknown artists—they wanted to meet the artists in person. They became friends with most of them, and most of them came to visit us. Janosch was over once as well: still young at the time, not yet famous, he bewitched us children with his magical art and sold our parents “two large oil paintings, one to Father because Mother liked it so much, and one to Mother because she wanted something to give Father for his birthday.” He also made a little illustrated book, From the Life of a Miner, clearly based on our father.

Like many of the other artists, Janosch lived in Munich. Munich and Düsseldorf were the cities our parents visited to see exhibitions, go to plays and restaurants, see friends and relatives, and shop for art and crafts, loden coats, jewelry, pottery, furniture, and presents.

Our large house filled up. In our living room were Arne Jacobsen’s “Swan” and “Egg,” Braun’s “Snow White’s Coffin,” and plastic stools from Milan that you could spin around. No wall units, no matching living room sets: individual pieces were mixed together. Our parents wanted to be surrounded by beautiful things, and what was modern was beautiful: Olivetti typewriters, Georg Jensen silverware. They were confident in their tastes, and they were right to be: things they bought at the time as avant-garde are now shown in museums as classics.

The heavy Biedermeier furniture they inherited was exiled to a room of its own that was actually never used, except when a great many people were visiting. “So fancy we are!” our father wrote. “Or at least: So uncomfortable our chairs are!” Still, our parents were thoroughly bourgeois. We all had to wear pigtails until our confirmation, except for Babs, the oldest (this was one of our father’s ideas); we all had to be home in the evening precisely on time. Our mother was not conceited but she could not stand stupidity, and she also knew the limits of her own tolerance. One of her favorite movies was Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?, in which Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn play a liberal couple who are anything but pleased when their daughter brings a black man home.

We always prayed before going to sleep and said grace before meals. “Come Lord Jesus, be our guest, / And let these gifts to us be blest”—here we clasped our hands—“ Bon appetit! Let’s all eat!” Then we threw ourselves on the food. The god we believed in was not a threatening, punishing god but a protector. Our mother believed in guardian angels, she had favorite saints (St. Anthony, finder of lost things, and St. Barbara, protector of miners), and she named her son after St. Martin, who shared what he had. Our parents’ religion was a rather worldly kind: political, artistic, and, above all, social. In 1961 they founded a youth group in Frillendorf, “in a battle against Pastor B.’s pious club”; our mother helped care for the needy; our father, as a presbyter, had influence in the parish. Later he gave up his office, over an artistic argument with the church: the paraments (hangings for the pulpit, altar, and lectern) that the pastor had commissioned from one artist were opposed by the other presbyters, and “Father cannot bear intolerance.” It was said of Pastor Wullenkord that he wanted to be a musician but was the son of missionaries; at Martin’s baptism, in Dortmund, he spoke “more about Mozart and Goethe than about our dear Lord.”

Every Christmas Eve morning, we were sent around the community to visit the old people. Our mother was glad to be rid of us during the final preparations, and the old people were glad to have someone to talk to. They told the same stories every year, mostly about their time as refugees in 1945. Every year, old Mr. Jäger told us what it was like when he and his wife had fled from East Prussia, now Poland, to Frillendorf on a horse cart. Every year, old Mrs. Haupt baked us New Year’s cookies and delighted us with her humor. When her health took a turn for the worse, at over ninety years old, and she lay on the sofa moaning, “Ah! Ah! Ah!” Finally she yelled at herself, “Say B for once, for God’s sake!”

Eventually, the house was emptier, quieter too—we were no longer children—and in 1971 we left Frillendorf and moved to a new building in Bergerhausen. Everything there was middle-class, green, and boring. “Whoever, like us, has felt true joy / Can never be unhappy again,” our mother wrote in a letter to a friend. The Ruhr District as we knew it came to an end as well. “Have you been to Essen?” asked the Dannon blueberry yogurt container that Martin reproduced in Through Puberty to Success. “Today there is only one coal mine operating in Essen, and the derricks are almost all gone. Essen’s biggest business today is retail. Essen is the Ruhr’s number one shopping city. Come take a shopping trip to Essen today!”

THE KIPPENBERGER MUSEUM

Our parents were hungry when the war ended—hungry for art, too. They went to the movies, to the theater, to exhibitions, including the very first documenta. Martin later told and retold the story about our grandfather wheeling him to the show in a stroller in 1955.

“Kippenberger knew perfectly well, ever since he was a child, that pictures, as the surrounding for sometimes worn-out feelings, can have an immensely positive effect,” Martin wrote about himself in Café Central. Pictures, our parents thought, make a house a home. In their wedding newspaper, our father said he wanted “pictures in all sizes and price points.” Once, when they were spending a week in Munich in a hotel near the train station, they unpacked their things, stowed their suitcases, and realized that “something was missing.” The pictures. The figurines. The books. “They healed the wound by using the shelf to display pictures, statues, and a tiny library.” By the end of the week, the soulless hotel room looked like their own apartment.

Decades later, when our mother was very sick in the hospital, she complained, “If only it wasn’t so bare in this room! No pictures, everything so insistently hygienic, all washable with disinfectants. Would a picture really mean a risk of infection? Or anything else that could give you something to look at and think constructive thoughts about?”

Our father called one of his first books—typed, illustrated, and properly bound— The Kippenberger Museum . Print run: one copy. The reader is led through the young couple’s miniscule apartment, ten by twelve feet, as though it were an actual museum, with the sink and coffee pot and and furniture and other objects described as works of art.