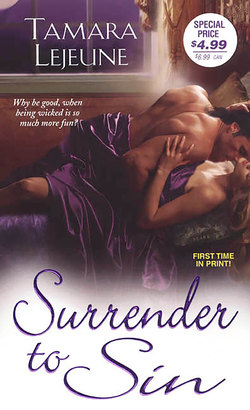

Читать книгу Surrender To Sin - Tamara Lejeune - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеWithout so much as a pageboy to assist her, Abigail Ritchie inched her way through the crowds of fashionable shoppers in Piccadilly, her packages stacked so high that only her chin kept them from tumbling out of her arms. Any casual observer who saw her slim figure buffeted this way and that by the pressures of the crowd might have mistaken her for a lady’s maid performing errands for her mistress. Indeed, the man who barreled into her, knocking her aside with his walking stick, had no way of knowing he had inconvenienced one of the richest young ladies in Britain. Had he been better informed, he might have been heartily sorry. As it was, he saw no reason to stop and offer either apologies or assistance to the solitary figure enveloped in a simple gray cloak. He simply pushed past her and continued on his way.

Abigail never saw him; her fur hood flopped forward into her eyes as she fell. Luckily, the Christmas presents tucked under her chin had not been dislodged in the collision, but she now had to regain her feet without the use of her hands. In the first attempt, she stumbled over her skirts as the heedless crowd surged past her. Her next attempt was forestalled by a pair of strong hands that picked her up and set her on her feet as if she had been a pawn on a chessboard.

“Ups-a-daisy!” said the owner of the hands. “On your feet, there’s a good girl.”

With her hood half-covering her eyes, Abigail could only see the lower half of her new acquaintance. He wore a long purple driving coat over buckskins and tall boots. In his gloved hands he carried a walking stick with a plain silver knob at the tip. A gentleman.

“Dulwich, as I live and breathe,” he muttered angrily.

Abigail shook her head until her hood fell backwards out of her eyes, then quickly planted her chin atop her packages again. “Was it Lord Dulwich who bumped into me?” she inquired.

“Bumped into you, child? Pretty charitable,” he said scornfully. “I’d have said he mowed you down like summer corn. I knew the man was a common drain, but I never thought him capable of knocking little girls down in the middle of a public street.”

He turned suddenly to smile at her, and Abigail caught her breath. She could only stare. He was, quite simply, the most beautiful man she had ever seen outside of a painting. With his dark hair, pointed beard, and the tiny gold ring he wore in one ear, he looked like a gypsy prince. His skin was unusually brown for an Englishman’s, which made his teeth look very white. She guessed his age at somewhere between twenty and thirty, but if he had claimed to be immortal, she would have believed him. He looked it.

“Beg pardon, ma’am!” he said gravely, though his gray eyes were laughing. “When viewed from the other side, you look precisely aged eleven and three quarters, or I should never have presumed to touch you. But I see from this side that you are quite grown up. Clearly, I ought to have pretended not to see you, like everyone else in this beastly mob.”

Abigail’s natural shyness rapidly transformed into terror. Handsome young men did not usually single her out for their gallantry. They certainly never teased her about her front or back sides. He made her so nervous that she almost wished he hadn’t stopped to help her at all. Beautiful gypsy princes, she quickly decided, were best enjoyed from a safe distance.

“So thoughtless of me,” he continued, evidently amused by her inability to speak. “As a gentleman, I ought to have made sure you were aged eleven and three quarters before I plucked you out of the dirt. Do please forgive my insufferable presumption. In future, I shall ask to see a baptismal certificate before I lend my assistance to any foundering thing in a petticoat.”

Abigail knew she ought to thank him, but her tongue was tied, and her mind had gone blank. Her face was more expressive, though; it turned bright red, invigorating her freckles.

She would have been quite surprised to learn that, despite an undeniable overactivity of freckles, the gentleman had not excluded her from the ranks of beauty. Without being smitten by her in the least, he liked what he saw: curly apricot-gold hair; big, light brown eyes; a wide, pink mouth under a straight, short nose. She looked to him like a good English girl, a credit to her parents, and someone who deserved better than a shove in the back, followed by a trampling.

“Thank you, sir.” Abigail finally forced the words out.

“That’s better; I thought you were going into shock.” With absolute false humility, he touched the brim of his hat. “Cary Wayborn, at your service, ma’am.”

Abigail gasped, her shyness broken by surprise. “Did you say Wayborn?” she cried impulsively. “Sir, my mother was a Wayborn!” As she spoke, one of her parcels began to inch forward, endangering the delicate balance of the entire stack.

“You seem to have developed a strange bulge in the middle,” he observed. “Since we are cousins, allow me to assist you.” With his walking stick, he pushed the box back into place.

“Thank you, sir,” she said breathlessly. “But are we really cousins, do you think?”

He studied her for a moment, seemingly oblivious to the bustling crowd surging past them. Abigail blushed again, knowing that he must be searching for some family resemblance. There was none, of course. How could there be, she thought hopelessly, when he is like a painting by Caravaggio, and I’m an unsightly mass of freckles capped by frizzy hair?

“You must be one of my Derbyshire cousins,” he said, at the conclusion of his scrutiny.

His familiarity with her mother’s family coaxed Abigail further out of her shyness. “Lord Wayborn is my uncle, sir. Though, to own the truth, I’ve never met him. It is generally thought that my mother married to disoblige her family.”

Cary politely ignored this last, rather indiscreet revelation. “Then we are indeed cousins,” he said. “And where were you going just now, before that feculent lout knocked you down?”

Abigail gasped in dismay. “You mustn’t call his lordship insulting names, sir.”

He snorted. “My dear cousin, I was at school with the feculent lout. Believe me, I do not insult. I merely describe. Now, where were you going? I’ll carry your boxes.”

“My father is to collect me at Mr. Hatchard’s Bookshop, but there’s really no need—”

“What a charming coincidence. I was on my way to Hatchard’s myself,” he said, grinning. “Fortunately, I know a shortcut.”

Abigail was not sure she believed a word he said, but before she could reflect on the propriety of accepting so much assistance from a stranger, he had exchanged her packages for his stick and was steering her boldly through the crowd. She was now doubly bound to follow him; he was carrying the servants’ Christmas presents, and she had his walking stick.

“I don’t often have business at Hatchard’s,” Cary said easily, glancing at her now and then as she struggled to keep up with him, “but I’m told a book makes a nice Christmas present.”

He turned into an alley next to a tobacconist’s shop, and Abigail stopped in her tracks. She had never been off the main streets of London before, and this rather noisome, narrow alley hardly inspired confidence. She could see no end to its darkness, and she imagined it to be filled with unsavory characters and stray animals carrying a variety of incurable diseases.

“Sir,” she called to him nervously, “are you quite sure this is the way to Hatchard’s?”

He had stopped to shift her pile of boxes. “If you could just take this little one under my left arm,” he said, just as a small package popped out and hit the ground. “Not fragile, I hope?”

“It’s gloves,” said Abigail, stepping forward unthinkingly to pick it up. She was now standing in an alley for the first time in her life. To her relief, no desperate underworld character jumped out at her from the shadows. Indeed, the only people there besides herself and her “cousin” were a few honest deliverymen unloading a cart.

“I thought of getting her gloves,” Cary murmured. “But my sister has got gloves enough for a dozen Hindoo deities.”

To carry the little package more easily, Abigail slipped her finger through the twine binding it. “A book is a handsome gift, too,” she said, holding her skirts up out of the frozen mud and horse manure dotting the cobbles. As she stepped around the manure-making end of the carthorse, she nearly collided with a broad-shouldered man carrying a large sack.

“Beg pardon, miss,” he said gruffly, not looking at her as he tossed his burden onto a waiting pile. Clutching Cary’s stick, Abigail scurried around him.

“My sister is engaged to be married,” Cary went on, apparently not noticing her near mishap, “so I thought I’d get her one of those books you females can only read after marriage.” He slipped past a large white sheet hung on a clothesline, and disappeared from sight. Abigail edged around the sheet, careful not to touch it, only to find that her guide was nowhere in sight.

“This way, cousin.”

He had turned into another alley, this one so narrow they were forced to walk in single file. “What sort of books would you consider off limits to an unmarried woman?” she asked curiously. Somehow it was quite easy to talk to the back of his head.

“Oh, you know,” he responded carelessly, “Tom Jones, Moll Flanders, that sort of thing.”

“I’ve read them both, and I’m not married,” said Abigail, inching forward in the darkness.

“And which did you prefer, cousin? The rake or the trollop?”

Abigail gave what she hoped was a sophisticated answer. “On the whole I found that Tom lifted the spirits while Moll rather depressed them. And you, sir?”

“Oh, I never read questionable material myself,” he airily replied. “What would my cousin the Vicar say? I shall leave all such risky endeavors to Mrs. Wayborn. While I am out shooting pheasant for her supper, let her be tucked up in bed reading Fanny Hill for my…edification. So much more useful than embroidering my handkerchiefs, don’t you agree?”

“I’ve never thought about it,” said Abigail, wondering what Mrs. Wayborn would think if she knew her husband was in the habit of cutting through dark alleys with strange young women.

“Do you feel the wall growing hot?” he asked presently. “Shall we?”

Before Abigail could reply, he opened a door. A flickering crimson glow suddenly outlined his face. The hellish light, however, was accompanied by the comforting smell of freshly baked bread. Abigail entered the bakery first, a wall of heat slamming into her as she passed a row of huge brick ovens. The baker’s apprentices gaped at them, making Abigail blush, but Cary was the picture of unruffled calm as he helped himself to a hot cross bun. “Cousin?”

Abigail mutely shook her head.

Cary led her swiftly through the front of the shop where customers lined up at the glass-front cases. Mainly servants from well-heeled Mayfair households, they parted respectfully to let Cary and Abigail through. In a few seconds, the cousins were out on the street again, and Hatchard’s signboard was just ahead. Abigail felt as though she had been brought safely through a hostile foreign territory, but now was within sight of the British embassy. She drank in the cold, clean air and heard with pleasure the chatter of busy shoppers.

Her companion appeared unaffected by the adventure. Obviously, he was as comfortable in the back alleys of London as he would be in the court of St. James or a gypsy gathering. Abigail smiled at him shyly. “Thank you, sir. It was kind of you to help a complete stranger.”

“But we are not complete strangers, cousin,” he pointed out. “We are relative strangers. Would you be good enough to open the door for me? My hands are a bit full.”

“Oh, yes, of course,” she said quickly.

Abigail felt safe inside Hatchard’s Bookshop. The staff knew her there, and the senior clerk, Mr. Eldridge, came forward to greet her personally. Miss Ritchie was a voracious reader, and, better still, she always paid her bills, which was more than the gentleman with her could say. Mr. Eldridge frankly could not account for their having arrived together.

Cary gave Abigail’s packages to an attendant, and she returned his stick, then extended her hand to him in farewell. “Sir, allow me to thank you again—” she began, breaking off as he gravely removed the package still dangling by a string from her little finger. Abigail decided that his departure would be a relief to her. If she was so incapable of behaving like a sensible woman in his presence, then the sooner he was gone, the better. “Goodbye,” she said quickly.

As he bent over her gloved hand, she completed her disgrace by diving behind the sales counter, to the considerable surprise of the clerk. Cary was perhaps even more astonished by the maneuver. “What are you doing?” he demanded, leaning across the counter to look down at her.

Abigail frantically gestured for him to be silent. “Lord Dulwich,” she whispered, her eyes round with terror. “He’s here! Please, sir, don’t give me away!”

“Wayborn,” said the Viscount of Dulwich, tapping Cary on the shoulder. As Cary slowly turned around to face him, his lordship went on, “I thought we’d seen the last of your purple coats. Heard you were rusticating in Hertfordshire amongst the haystacks. On a pig farm, or some such thing. What’s the place called? Tatty-wood? Tinklewood?”

Cary leaned against the counter. “I’d tell you, but then you might visit me.”

His lordship sniffed, then turned to the clerk. “You there! I’m looking for some idiotic rubbish called Kubla Khan. The assistant is too stupid to help me, and I’m rather in a hurry.”

The clerk answered as smoothly as he could with Abigail crouched at his feet. “I regret to inform your lordship that Mr. Coleridge has not yet published his famous fragment. It will be out in the next few months, I believe.”

The Viscount was infuriated. “But I am Lord Dulwich, man. I want it now.”

“The man can’t pluck a book out of thin air,” Cary Wayborn pointed out reasonably.

“This is no concern of yours, Wayborn,” his lordship snapped. “But that’s you all over, butting in where you don’t belong. Have you no conduct?”

“That’s rich, coming from you,” Cary said. “When I just saw you knock a girl to her knees in Piccadilly without so much as a ‘Pardon me.’ If that’s your idea of conduct—”

“What girl?” said Dulwich, with a sneer marring his aristocratic features. “A pet of yours, perhaps? I daresay she’s been knocked to her knees before and will be again.”

Abigail stifled a gasp. Never in her life had she heard such rudeness.

“As a matter of fact, the young lady is my cousin,” Cary said coldly.

“I beg your pardon,” said Lord Dulwich, without so much as a hint of regret. Indeed, he sounded rather proud that his insult had pricked its mark. “You should tell your cousin to watch where she’s going. The stupid chit stepped right into my path. It was her fault entirely.”

“No, it wasn’t,” Cary said hotly. “I saw the entire disgraceful incident. You shoved her in the back, and, let me tell you, when I bring the matter up at White’s—”

“You wouldn’t tell the Club!” said his lordship, a whine entering his haughty voice.

“You sniveling toad,” was the only reply his lordship received.

“What do you want, Wayborn?”

“I want an apology, Pudding-face,” said Cary. “My cousin don’t wish to see you, of course, so it will have to be in writing.”

Mr. Eldridge was very prompt in providing writing materials for his lordship at no charge. To Abigail’s astonishment, Lord Dulwich offered no protest.

“What’s her name, this cousin of yours?” he inquired testily, dipping the pen in the well.

“I’m not telling you her name, Pudding-face,” Cary said scornfully. “Write this: ‘The odious Lord Dulwich humbly extends his profoundest and most sniveling—!’”

“Look here!”

Cary ignored him. “‘Most sniveling apologies to the young lady whom he so savagely assaulted in Piccadilly this afternoon. By his failure to offer any apology or assistance to her on that occasion, he has forfeited his right to call himself an English gentleman. Furthermore, his lordship does hereby attest and affirm that he is in fact the most feculent lout ever to disgrace the British empire. Yours in utter moral failure, et cetera, et cetera.’”

“Look here!” Dulwich protested. “Can’t I give her ten pounds instead? Twenty?”

“In my family, we don’t exchange currency for insults,” said Cary. “I need hardly tell you how the members of my Club will react if I tell them what you did. Besides, where would you get twenty pounds? Your father’s cut off your allowance, or so you said when you asked me to hold onto a certain I.O.U. just a little longer.”

“For God’s sake, lower your voice!” Dulwich snarled.

“Now sign and date it, if you please.” Cary took the scrap of paper from the Viscount, inspected it briefly, then seemed to forget all about the matter. “I’m looking for Tom Jones, my good fellow,” he pleasantly told the clerk. “Would you be so kind as to direct me to it?”

“I was here first,” Dulwich objected. “I want Kubla Khan, and I want it now.” He rapped on the counter with his stick, and the unhappy Mr. Eldridge offered to put his lordship’s name on the waiting list. “List?” the Viscount demanded. “What list? Who’s on it?”

“Quite a number of our best customers, my lord,” Mr. Eldridge replied. “Indeed, the demand has been so high that the publisher has already called for a second printing.”

“Very well. Put me on your beastly list,” said Dulwich impatiently.

“I’d no idea you were such a devotee of Mr. Coleridge,” Cary remarked.

“I’m not,” his lordship growled. “I despise all poetry, and all poets too. But, unfortunately, my betrothed is rather excitable on the subject.”

Cary laughed shortly. “Don’t tell me you’re engaged. Who is the poor creature? I should like to send her my condolences on black-edged paper.”

“The lady is well aware of her good fortune,” his lordship coldly replied. “Look here, you fool! If the book arrives before January the Fourteenth, I shall buy it. If not, never mind.”

“And what, pray, is the significance of January the Fourteenth?” Cary asked.

“That is my wedding day,” Dulwich replied, “not that it’s any business of yours. I’ve no intention of wasting money buying my own damn wife a silly book.”

“Very sensible of you,” said Cary. “And you say the lady is aware of her good fortune? Capital. Allow me to wish you joy. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a man so deeply in love. Why, you’re positively radiant.”

Dulwich’s face turned nearly black with fury. “I am not in love with her, you ass,” he hissed. “I want her father’s money, and she, I suppose, wants to be a viscountess. When we marry, I shall be able to settle all my debts, including that little bet of ours. Look here, Wayborn, if you start spreading it around that I’m marrying for love, I shall have to call you out.”

“Steady on,” said Cary, stifling a laugh. “I shan’t tell a soul you’re after her money. After all, if you don’t get her money, I may never get mine.”

“What are you doing there, you damn fool?” his lordship suddenly snarled.

Abigail nearly jumped out of her skin. But Dulwich had not discovered her hiding place; he was addressing Mr. Eldridge. “Imbecile! You’re putting my name at the bottom of the list. Who is entitled to come before my Lord Dulwich? The Misses Brandon? I think not.”

As Mr. Eldridge watched in dismay, his lordship seized the book and proceeded to cross out the Misses Brandon in order to insert his own name at the top of the page. “I shall make all my friends aware of the staff’s impertinence,” said Dulwich, jerking on his gloves, “and I predict that Hatchard’s will be out of business in a month’s time!”

He paused, as though waiting for Mr. Eldridge to seek to detain him, and then Abigail heard the doorbell ring as his lordship left the shop. A moment or two passed before she felt safe enough to lift her head. Mr. Wayborn was leaning across the counter looking down at her. “You can come out now, monkey,” he said lightly. “The nasty man has gone away.”

Abigail climbed to her feet. “I daresay you think me rather childish,” she stammered, “but I simply can’t bear scenes. It would have been so very embarrassing to see him.”

Cary took her hand and led her around the counter. “I think you did exactly right,” he said. “I only wish I had the courage to run and hide whenever I see the old Pudding-face.”

“I wasn’t hiding,” she said defensively. “I–I dropped my gloves.”

“My dear infant, you’re wearing them.”

“No, not these—the gloves I just bought.” She had the little box wrapped in brown paper to back up her story. “And then, of course, I thought it might look a little odd if I were to suddenly appear from behind the sales counter…so I rather thought I’d better stay where I was.”

“I see,” he said, not believing a word of it. Gravely, he held Lord Dulwich’s written apology out to her. “His lordship wanted you to have this.”

Abigail shyly plucked it from between his gloved fingers. “Did he actually write all those things you told him to?” she exclaimed. “How could he be sure I wouldn’t expose him?”

He laughed. “Because you’re my cousin, that’s why. You’re a Wayborn.”

He looked at her very warmly. To cover her embarrassment, she quickly turned to the clerk. “You will put the Misses Brandon back on the list for Kubla Khan, won’t you?”

“Of course, madam,” the clerk assured her. “It was remiss of me not to tell his lordship that this is the sixth page of a very long list. I shall place the Misses Brandon at the bottom of page five.” As he wrote, he smiled politely at her. “Might I help you find something, madam?”

“Please attend the gentleman first,” said Abigail. “I’m just waiting for my father.”

“In that case, let me bring you something to look at while you wait,” said the clerk. “I won’t be a moment. I’ll have my assistant find your book for you, sir,” he told Cary. “I believe you were interested in Mr. Fielding’s History of a Foundling, popularly known as Tom Jones?”

“Who is this Kubla Khan?” Cary asked Abigail when the clerk had gone. “There must be two hundred names on that list.”

“Do you not know the story, sir?” Abigail asked excitedly. “The poem first came to Mr. Coleridge in a dream. When he woke up, it just sort of poured out of him onto the page, as if the poet were merely a conduit between this world and the next.”

Cary struggled to keep a straight face. “Fascinating technique,” he remarked.

“Unfortunately, as he was putting it down on the page, he was interrupted by a man from Porlock, who would talk business, and when poor Mr. Coleridge sat down to write again, the rest of the poem had passed away like the images on the surface of the stream into which a stone has been cast. Why are you smirking?” she demanded.

He was thinking that she was quite a pretty girl when she forgot to be shy.

“Was I smirking? I beg your pardon. But it should be rather obvious to anyone that Mr. Coleridge is simply too lazy to finish his work. He’s invented a rather feeble excuse, a fairy story, to help him sell a fragment. Is that not some excuse for smirking, if indeed I smirked?”

“What right have you to accuse Mr. Coleridge of making up a fairy story?” Abigail demanded huffily.

“You’re quite right,” he murmured, though he still appeared amused rather than contrite. “I withdraw my cynical remarks. I withdraw my smirk.”

“I should think so indeed,” said Abigail crisply, as Mr. Eldridge returned with a book.

“Good God,” said Cary. “Blake’s Songs of Innocence, unless I miss my guess.”

Mr. Eldridge looked at the gentleman with approval. “Songs of Innocence and of Experience, sir. A combined volume, very rare. Mr. Blake prints them all himself, you know.”

Abigail shook her head regretfully. “I’m afraid I don’t quite understand Mr. Blake,” she said. “I read part of Heaven and Hell last winter, but it was so strange that I had to set it aside for my own peace of mind. And, you know, people say he’s not a patriot.”

“Not a patriot?” said Cary, frowning. “What do you mean?”

Abigail dropped her voice almost to a whisper. “During the war, he was suspected of printing seditious material, and when the soldiers came to his door and said, ‘Open in the name of the King!’ Mr. Blake answered, from behind the door, ‘Bugger the King!’ Which, I daresay, is not a very nice thing to say about one’s sovereign,” she quickly added.

“Or anyone else’s sovereign,” Cary agreed, just managing to keep a straight face. “But the war is over now, cousin, and we are once again free to insult our betters as much as we please, without fear of reprisal. In my opinion—if you happen to be interested in my opinion?”

“Yes, of course,” Abigail said civilly.

“In my opinion, Mr. Blake is a visionary poet without the aid—or excuse—of opium, which is more than your Mr. Coleridge can say. But if Blake is too strong for you, cousin, there’s bound to be a little Wordsworth lying about the place.”

Abigail was indignant. “I rather like Mr. Wordsworth!”

His smile widened. “I suspected as much. He’s so perfectly harmless.”

“It really is a very fine volume, madam,” interjected Mr. Eldridge, still hoping for a sale. “Nothing frightening in it at all. If nothing else, Mr. Blake is a master of the copperplate.”

“If the tiger is good, you should buy it, cousin,” said Cary decisively, reaching for the book. “There,” he said drawing her attention to a poem entitled, “The Tyger.” At the bottom of the page was a cartoon of a muscular beast with amber eyes as big as saucers. Its fiery orange body bore irregular umber stripes, but in no other way did it resemble a tiger.

“It appears to be smirking,” said Abigail critically. “And the poem…It’s like a nursery rhyme, isn’t it? ‘Tyger Tyger, burning bright, in the forests of the night…’”

“Remind me never to visit your nursery!” Cary said, laughing.

Mr. Eldridge looked inquiringly at Abigail. “Madam?”

She shook her head. “Perhaps the gentleman wants it.”

“Excellent tiger,” said Cary. “Wish I could afford it, but I’m rather as poor as Adam at the moment. My man of affairs has ordered me to retrench. You wouldn’t happen to know of anyone looking for a house in the country, would you, cousin? I’ve got one to let, and I could certainly use the rent. It’s an old dower house, a cottage really. Only six bedrooms.”

“Have you tried advertising?” she asked politely.

“Good Lord, no,” he answered. “I couldn’t possibly advertise. Advertisements always draw the very worst sort of people: people who read advertisements. If you should hear of anyone interested in a place, do please send him my way,” he said, feeling about his waistcoat for a card. Finding none, he took Dulwich’s apology from her, turned it over, and scrawled rapidly on the back: “Cary Wayborn, Tanglewood Manor, Herts.” “A recommendation from my fair cousin would be enough for me,” he added with a wide smile.

Flattered, Abigail tucked it into her reticule just as the assistant appeared with Tom Jones.

Mr. Eldridge took a ledger from beneath the counter. “Oh, dear,” he said, clucking his tongue. “There appears to be an outstanding balance on your account, sir. Nearly ten pounds.”

“Is there?” Cary replied, unconcerned. “Remind me about that sometime, will you?”

“I think he’s trying to remind you of it now,” Abigail pointed out.

“Is he?” Cary said sharply. “Are you trying to remind me of it now, Eldridge?”

“No, indeed, sir,” the clerk said meekly. “Would you like this wrapped? We’ve some very special Christmas paper printed with holly wreaths. It was the young lady’s idea.”

Cary glanced at Abigail. “What, this young lady?”

“It’s been a very popular service this season. Only a penny more, sir.”

“By all means.” When Mr. Eldridge presented him with the package tied up with a red ribbon, Cary seemed pleased. “I daresay my sister will think I did it myself. And now I must bid you adieu, cousin,” he said, turning to Abigail.

“Must you go?” Abigail blurted without thinking as he took her hand. “I’d like to present you to my father,” she quickly added. “He’ll want to thank you for your kindness to me.”

“I should very much like to meet your father, cousin, but my aunt expects me in Park Lane. I was meant to be there three quarters of an hour ago, and I am never late.”

Abigail reddened. “It’s my fault you’re late now. I’m so sorry.”

He smiled. “You’ve provided me with an excellent excuse for my tardiness, at any rate.”

Though she in no way wanted him to go, Abigail was relieved when he did. Having one’s wits scrambled by a good-looking stranger was decidedly unpleasant. Much better to be left in peace with a cup of tea and a quiet volume of Wordsworth.

Mr. Eldridge was more than happy to provide her with these comforts. He showed Abigail to the private sitting room and brought her a pot of tea and The White Doe of Rhylston. “I suppose my cousin, Mr. Wayborn, buys a lot of books for his wife,” Abigail remarked, idly opening the little green book to its title page.

“Did Mr. Wayborn marry?” Mr. Eldridge replied, pouring her tea into a Worcester cup. “Oh, dear. I failed to wish him joy. Shall I put The White Doe on your account, madam?”

“No,” Abigail said, arriving at a sudden decision. Closing the book, she held it out to him. “No, I think I’ll take the Blake after all, Mr. Eldridge.”

“Very good, madam,” said Mr. Eldridge, pleased.

When Mr. Ritchie arrived to collect his only child some thirty minutes later, he found her deep in thought over a book, staring at a picture of a smirking tiger. “Abby! You will never guess who I saw in Bond Street just now,” he said, in his thick Glaswegian accent. “My Lord Dulwich, that’s who. Someone’s getting sparklers for Christmas, I shouldn’t wonder!”

Abigail smiled fondly at her father. The sole proprietor of Ritchie’s Fine Spirits, est. 1782, was not a gentleman, but he was still the best man she had ever known. He was also one of the richest men in the kingdom. “He certainly knows how to make an impression,” she tactfully agreed with him. “Would you be terribly disappointed if I didn’t marry him after all?”