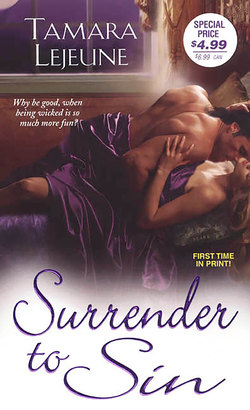

Читать книгу Surrender To Sin - Tamara Lejeune - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 4

ОглавлениеOne of the Manor’s wrought iron gates had come loose from its post and was propped against the wall of what Abigail supposed to be the gatehouse—a dingy stone box that looked more like an abandoned rookery than a human domicile. The manor house did not disappoint, however. With its large, mullioned windows and its chimneys rising like decorative spires from the roof, Tanglewood was as fine an example of a Tudor country house as she had ever seen. The red brick facade was clad with ivy, and outside the entrance was a small timber portico, with room enough inside for two rustic benches and a boot scraper.

As the coach rolled up the drive, Abigail saw Cary Wayborn step out from the portico, a barking dog at his heels. The animal had the fox-like head, short legs, and deep, bow-front chest typical of a Welsh corgi. By concentrating on the dog instead of the master as he helped her from the coach, she found she could breathe quite normally.

“The house is much too big for us, Mr. Wayborn,” she said worriedly, turning to help Paggles, only to find that the efficient Evans had the situation in hand. “The rent we paid for the Dower House can’t possibly be enough.”

The corgi launched itself at Abigail, demanding its fair share in the conversation. Its stump of a tail was wagging so hard its entire rear end was in motion. “Quiet, Angel,” Cary snapped, to no avail. The dog jumped energetically at Abigail’s skirts. Abigail solved the problem by scooping the small animal up in her arms.

“Worst dog ever,” Cary remarked lightly.

“No, indeed,” said Abigail, which Angel mistook for an invitation to lick her face.

“There’s no question of asking Mr. Leighton for more rent,” Cary added. “It’s not his fault my tree forgot its manners, after all.”

It had not occurred to Abigail before that Cary would think Mr. Leighton responsible for the rent. Of course, he had no way of knowing the truth. She was no longer Miss Ritchie, the Scotch heiress who had jilted Lord Dulwich; she was now the anonymous Miss Smith, ward of Mrs. Spurgeon.

They hurried inside out of the blowing snow. The entrance hall was lit by a huge fire blazing in the massive stone hearth. Abigail set Angel on the floor and looked around, idly brushing at the short red hairs the dog had left on her cloak.

Angel ran straight to the fire where two well-worn tapestry chairs had been arranged with a large footstool littered with newspapers set between them. A few crewel-work cushions had been placed on the deep wooden sills beneath the tall windows, but the room offered no other seating. Only one or two carpets had been put down on the floor, which was stone in some places and in others composed of odds and ends of timbers laid out in a hound’s tooth pattern. The walls were of beautiful linenfold paneling, darkened by smoke and age, and the coffered ceiling, which was rather low, featured the double rose of the Tudors.

Abigail, who had always lived in the most modern, convenient London houses, instantly fell in love with it, musty smell, smoking chimney, and all. She could imagine the place filled with sixteenth-century ladies and gentlemen, the ladies in rich brocade skirts and ruffs of starched white lace, the men in velvet doublets and hose. She imagined how Cary Wayborn might look in doublet and hose, and decided he would do very well. He already had the pointed goatee and golden earring favored by the young men of Queen Elizabeth’s court.

“Mrs. Grimstock is making us tea,” said Cary, clearing away the newspapers. Abigail hurried to help Paggles into one of the chairs, while Evans went to find the housekeeper.

Cary watched curiously as she removed her cloak and placed it over the old woman like a blanket. Though rather too sensible in its design to be fashionable, Abigail’s dark blue dress was of good quality. It fit her slim body very well, and the deep, rich color made her short, curly hair look more than ever like butterscotch. Even from behind, there could be no mistaking her for a child. Cary felt his blood grow warm. It had been far too long since he had enjoyed a woman, and judging by this one’s reaction to him, it was not going to be a very long conquest. Though she was obviously a virgin, he was experienced enough to know the many ways they could enjoy themselves without spoiling the girl completely. All he needed was to get her alone.

Cary disposed of his newspapers and returned as Abigail was pulling off her gloves. “He eats gloves,” he warned her, removing what proved to be a walnut from the dog’s mouth. “Shoes too—sometimes with the people still in them.”

To Abigail’s enormous relief, she found that, when her handsome, unmarried cousin was at one end of the room, and she was at the other, her bashfulness remained under control. It was only when he got within arm’s reach that she turned into a stammering fool.

“He’s still a puppy. I daresay he’ll grow out of it,” she said intelligibly, just as the housekeeper arrived with the tea tray. The folding table was in its collapsed state at one side of the fireplace, and, as Abigail was closer to it than anyone else, she set it up without thinking.

“Mrs. Grimstock,” Cary said sharply. “This is my cousin, Miss Vaughn, from Dublin. She hasn’t come all this way to set up tables for us.”

Mrs. Grimstock did not look like a Grimstock at all, but was rather a plump, middle-aged woman with a pleasing scent of candied ginger. “I beg your pardon, Miss Vaughn,” she cried.

“Smith,” said Abigail, confused to suddenly have two names that were not her own. “I’m perfectly capable of setting up a tea table, Mr. Wayborn. But my name is Smith.”

Cary frowned slightly, but accepted the correction gracefully. “Yes, of course,” he said smoothly. “My cousin, Miss Vaughn-Smith. Or is it Smith-Vaughn? I quite forgot you were hyphenated.”

“I am not in the least hyphenated,” said Abigail, staring at him. “I am simply Miss Smith. And I’m not from Dublin. Whatever made you think so? I’m from London.”

“Yes, of course,” he agreed, beginning to laugh. “I must be drunk! Mrs. Grimstock, this, of course, is my cousin, Miss Smith, from London. She is not my cousin Miss Vaughn from Dublin, after all. I hope that’s clear. Will you do me the honor, cousin?” he added, as Mrs. Grimstock withdrew.

“Do you the honor, sir?” For a moment Abigail stared, confused. “Oh, the tea! Yes, of course,” she said quickly. “How do you take yours, Mr. Wayborn?”

He grinned at her audaciously. “With a spot of whisky, generally,” he said, waiting for her gasp of ladylike dismay.

“There doesn’t seem to be any,” she said, dismayed, to be sure, but not gasping. “Shall I ring for the servant?”

“Here,” he said, pulling out his flask, wondering how far she would take the joke.

To his astonishment, she quietly took the whisky and poured it with a liberal hand into both cups. “Sugar?”

“Two, please,” said Cary. As he came forward to take his laced cup, he could scarcely keep a straight face. He fully expected her to choke on her own tea-and-whisky, but to his astonishment, it seemed to slip quietly down her throat, as if by long-established custom.

“One doesn’t often get such quality here,” Abigail remarked, unaware she had done anything controversial. “The Irish like to keep the best for themselves.”

“My groom’s an Irishman,” Cary explained. “He can get me anything.”

“I do like a little Irish in my tea. Though it’s not good for you at all. Not like scotch.”

Cary choked.

“Have I put too much in your cup?” she asked, concerned. “It does take getting used to.”

“I’m all right,” Cary said with dignity. “Is…Is scotch good for you, do you think?”

“Oh, yes,” Abigail said seriously. “A quaich a day is absolutely essential for the blood.”

“What in God’s name is a quake?” Cary wanted to know.

“About this much.” With her thumb and index finger, Abigail measured two inches.

“I wouldn’t know what a quake does for the blood,” said Cary, laughing. “But I can tell you from experience that a bottle is very bad for the head. I brought a case of scotch up here when I first moved in, drank it out of sheer boredom, and it nearly killed me.”

Abigail smiled to herself. Her Glaswegian father had always told her that Englishmen could not hold their liquor, so she did not think any less of her cousin for his admission. “This is a beautiful house,” she said presently.

“Is it?” he replied, shrugging. “If you like drafty old piles. It started out as a cow byre.”

She seemed deeply interested, so he went on, “As the Cary family prospered, they started adding on rooms. Things really got going for them when Henry VIII granted them a few thousand acres belonging to some stubborn Catholic neighbors, and by the time Elizabeth came to the throne, they were pretty well-established. In honor of the Virgin Queen, they built the house in the shape of an E.” He set his cup on the mantel. “Shall I give you the tour?”

Abigail glanced at her old nurse, but Cary said quickly, “Let her rest. The servants will look after her.”

“But Mrs. Spurgeon and Mrs. Nashe must be at the inn by now.”

“It’s very likely they will have to stay the night,” he told her. “It’s been snowing all afternoon. I don’t know that a carriage could get through. You don’t mind being trapped here with me, do you?” He held out his hand to her, and smiled.

“But you will be at the gatehouse, surely,” she objected nervously.

“Yes, of course,” he said, pulling her to her feet. “Though I really think you ought to ask me to stay for dinner. I hate dining alone. Then, after dinner, you should play cards with me.”

He delighted in the way her eyes grew big with alarm at the prospect of spending an evening alone with him. “Come now, Miss…er…Smith, we’re cousins. Surely there can be nothing improper in dining with one’s own cousin. You would not send me to the gatehouse with no supper and no company—apart from my misshapen dog, that is.”

“What’s the matter with your dog?” she asked, puzzled.

“What’s the matter with him?” he said, drawing her along with him towards the next room. “My dear girl, you must have noticed the manufactory forgot to give him legs and a tail.”

“He’s a corgi, Mr. Wayborn,” Abigail chided him. “He’s absolutely perfect just as he is.”

In complete agreement with her, Angel got up on his hind legs and licked her hand.

“You mean you’ve seen his kind before?” Cary asked curiously.

She nodded. “Yes, in Wales. The farmers use them to drive their cows down the road.”

Cary chuckled. He now realized that she was teasing him, probably getting him back for leading her to believe he had a mute wife tucked away somewhere. There was no possible way a little dog like Angel could be used to herd anybody’s cows. “I generally use mine to chew on the furniture,” he said cheerfully. “If you like old family portraits, come have a look at these.”

“Oh, yes,” said Abigail, almost tripping over the excited corgi. Angel had not expected her to move so quickly and immediately tried to herd her back to her chair. Failing that, he decided to nip at her heels to make her go faster. Cary pushed him aside with his foot and closed the door in his face, after letting Abigail through. The dog could be heard barking hysterically.

The fire had not been lit in the next room and it was noticeably colder, though the rows of mullioned windows admitted enough light for Abigail to see the paintings hung on the wall. At a glance she recognized the work of Bettes, Gower, Van Dyck, and Lely. Clearly Mr. Wayborn’s ancestors had spared no expense in immortalizing themselves. She was surprised by how many of the people were fair-haired; the Wayborns were usually dark.

“These are my mother’s people,” Cary explained. “The Carys must have had some Viking blood, I think. But here’s a fine young Wayborn you know.” He stopped before a portrait of a fair woman with three children, painted by George Romney. The children were as dark as the woman was fair. “My mother,” said Cary. “This handsome fellow is me, of course.”

Abigail smiled at the little boy in short coats teasing a tabby cat with a ball of yarn.

“And that loathsome creature polluting my angelic mother’s lap is my sister Juliet.”

“She was a lovely baby,” said Abigail severely.

“A blot,” he insisted. “Take my word for it. Sucked her thumb until she was nine.”

“Who is that?” Abigail asked, pointing out the older child standing behind Cary’s mother.

“My elder brother, Benedict. My half-brother, I should say. His mother was my father’s first wife, but Father insisted on all his children being in the portrait. Poor old Ben! He doesn’t seem to want to be there, does he?” He moved away quickly and stopped at another painting. “Here’s a lady that looks a bit like you, cousin. The infamous Lettice Cary.”

The painting, most definitely by Anthony Van Dyck, showed a green-eyed young woman with hair the color of a fox’s pelt peeping from beneath a jeweled cap. Her delicate face was nearly white, but the artist had modeled it carefully in his palest colors, giving it life. Lettice’s golden brows and lashes had been painted hair by hair with the artist’s finest brush, and the cheeks and small mouth were stained the faintest imaginable pink. She was dressed in Jacobean finery, her white dress studded with pearls and emeralds, her upstanding white lace collar like an intricate spider’s web against the dark wood paneling behind her. Seated on what looked like a throne hung with heavy scarlet and white curtains, she seemed to be leaning backwards slightly. Abigail saw no resemblance to herself whatsoever.

“Do you really think I look like her?” she asked curiously.

“Only a little,” he replied. He looked at her, then at the painting. “You both have saucy eyes. Aren’t you going to ask me why she’s infamous?”

“Why?” asked Abigail, turning beet-red. No one had ever described her light-brown eyes as “saucy” before. She decided he was merely teasing her again.

“When she was quite forty, she ran away with her lover, an Italian musician twenty years her junior. How is that for a spot of scandal? This portrait was painted when she was a young bride, of course, but she already looks pretty restless, wouldn’t you agree?” He placed his hand on Abigail’s shoulder as he spoke.

Abigail could neither agree nor disagree; her tongue was tied, and all she could feel was his hand burning through her clothes like a hot iron.

“The ring on her finger is still in the family,” he added, as Abigail moved away without replying. “The Cary emerald. I’d show it to you, but it’s kept in our vault in London.”

“I daresay these portraits are worth more than your emerald, sir,” Abigail murmured.

“Perhaps. But no one wants to buy the men, and I can’t bear to part with the ladies.”

Abigail caught sight of a set of miniatures arranged inside a curio table beneath a window. “These are very fine, sir. You have Henry the Eighth, four of his wives, and his daughter Elizabeth, all set in gold. You even have Anne Boleyn,” she added, tapping the glass. “Most people would have thrown out her portrait when she was beheaded.”

Cary pretended to be interested for the pleasure of moving closer to her. She was so engrossed in the miniature portraits that she forgot to shy away from him. “I daresay she was restored to the case when her daughter Elizabeth became Queen,” he theorized.

“You’re missing two Catherines,” Abigail pointed out. “Catherine of Aragon, and Catherine Howard. One divorced, the other beheaded. If your collection were complete, it would be worth a small fortune.”

Cary’s interest became genuine. “How small, do you think?”

“Easily a thousand pounds,” Abigail said promptly. “Quite possibly more.”

He stared at her. “You’re mad. A thousand pounds?”

She nodded earnestly. “If you could find the two Catherines, in good condition.”

“There are some other miniatures in my study,” he said, leading her quickly through a door down a long, dark hallway into a small, untidy chamber with low casement windows. Unlike the formal rooms she had already seen, this one had not been paneled, and the original plaster and beams were exposed. Cary went to a large cabinet and, after rummaging in a few drawers, brought her a large box in which a half dozen miniature portraits had been casually jumbled together. He began taking them out and arranging them on his desk, after clearing a stack of unopened correspondence out of the way.

Abigail picked up one. “Why, this is Henry’s daughter, Mary,” she exclaimed. “How extraordinary. I’ve never seen a miniature of Bloody Mary, sir. She was so hated in her lifetime, there wasn’t much demand for her portrait, large or small.”

He shrugged. “Worth much?”

Abigail shook her head in regret. “As I said, she wasn’t very popular.”

Cary held up another, this one depicting a slim girl with carroty hair and demurely folded hands. “Could this be a young Elizabeth?”

Abigail smiled at him. “That, Mr. Wayborn, is Catherine Howard. And this boy here is Edward VI, son of Henry and his third wife, Jane Seymour.”

There were several more miniatures in the box that Abigail could not identify, but no Catherine of Aragon. “If you could find her, Mr. Wayborn, you would have an enviable collection; King Henry, all six of his wives, and all three of his children. I might value that as high as three thousand pounds.”

“I’d sell it in an instant.”

“Shall we put Catherine, Mary, and Edward in the table with all the rest?” Abigail moved towards a door, but found that it was locked.

“That door leads out to the gardens,” Cary said, leading her to the correct door. “I’d take you, but the grounds aren’t much to look at in winter, unless you like brambles and snow. We do have a traditional knot garden that stays green, if you’d like to see that.” He smiled to himself, thinking it would be great fun chasing his skittish cousin through the maze.

Abigail demurred because of the snow, which was still falling.

“I suppose eventually I shall put in some modern French windows,” he said on the way back to the portrait room with the miniatures. “At Wayborn Hall, where I actually grew up, we have French windows leading out to all the terraces.”

“On no account,” cried Abigail, quite forcefully, “are you to put in French windows, Mr. Wayborn! You mustn’t do anything to compromise the historical integrity of the house.”

Cary raised his eyebrows. “It’s my house, cousin,” he reminded her, laughing.

“But you can’t!” cried Abigail. “It would spoil the whole house if you did.”

Cary grinned. When provoked, she quite forgot to be shy, as she had when he’d questioned Mr. Coleridge’s integrity in Hatchard’s Bookshop. “I suppose you think my ancestors were wrong to put in chimneys and staircases when they had perfectly good fire pits and ladders.”

“No, of course not,” said Abigail. She held strong views on the subject, he could tell, but she struggled to present them effectively, while he, without caring half as much, could talk circles around her. “A chimney is one thing. But to put French windows in a beautiful old Tudor house—! I think that would be a crime, Mr. Wayborn. You ought to be restoring Tanglewood to its original state, not disfiguring it with French windows.”

Cary couldn’t help laughing. “I told you what it was originally—a cow byre! Do you really want me to restore it to its original state with a bunch of moilies and milkmaids?”

Abigail pressed her lips together. She could not compete with him in open debate, but, in her view, the only way to truly win an argument was to be right, and he was definitely wrong.

Cary couldn’t resist teasing her throughout the rest of the first floor rooms, threatening to replace every arched doorway with a French window. Abigail did not once laugh.

“Don’t sulk,” he finally told her as they came to the main staircase. “I couldn’t possibly afford to have French windows put in. The historical integrity, as you call it, is perfectly safe.”

Abigail was delighted to see the exposed timbers at intervals in the plaster walls upstairs. In the hall, the plaster had been painted a green that had darkened with age, but clear, lighter areas showed where paintings must have hung until quite recently. She guessed, correctly, that Cary Wayborn was selling off the treasures of the house little by little.

“These are the two best rooms,” he said, coming to two doors at the end of the hall. “Since you’re my cousin, I think you should have one of them. Mrs. Spurgeon, I suppose, may have the other.”

He opened the first door.

It was not a very large room, but Abigail thought it was perfect. The casement window allowed in plenty of light. The paneled walls were painted a creamy white, and the coffered ceiling was decorated with the red and white double rose of the Tudors, symbolizing the union of the Lancasters and the Yorks. The feather bed was set on a huge, intricately carved box of walnut. From its four posts hung red and white crewel-work curtains. The only other furnishings were a large wardrobe against one wall, a small washstand with a mirror, a little chair near the window, and a stone fireplace that, at present, was cold and dark.

“I know this room!” Abigail exclaimed.

“Seen it in a dream, have you?” he teased her. “In novels, the heroine always comes to a room she has seen before in a dream. She usually faints in the arms of the nearest man.”

“I recognize it from the painting downstairs,” she told him sensibly. “This must be where Lettice Cary sat for her portrait.” She pointed at the red and white bed hangings. “She must have sat there, on the bed.” It occurred to her all at once that she was alone in a bedroom with a man, and she became rather flustered, to his immense enjoyment.

“I daresay only Lettice and her husband would have known she was sitting on her marriage bed. Apart from the artist, of course.” He grinned. “I always thought she looked as though she might fall over backwards at any moment. Now I know why.”

“This is not original to the room,” she said, moving quickly to the wardrobe.

“No,” he agreed, “but there’s a secret to it I think you’ll like.”

“What sort of secret?”

“I’ll show you,” said Cary, opening the heavy carved doors. “There’s a secret door in here. If you press it in a certain place, the panel slides back.”

“A door to a secret room?” Abigail asked eagerly.

“Not a secret room, more’s the pity. Just an ordinary, everyday secret passage between two ordinary, everyday bedrooms.” He gave her his wickedest smile.

“But why would anyone want that?” she asked, puzzled. “Why not simply go out into the hall and use the door there? Why go crawling around through somebody’s wardrobe? It makes no sense.”

“It’s all very strange and mysterious to me, too,” said Cary, his gray eyes laughing at her innocence. “But I must correct you on one point. One does not go crawling through the wardrobe. It’s really quite as comfortable as walking through a doorway.” He demonstrated this by stepping inside the wardrobe. “See? I needn’t even crouch down.”

“But there aren’t any clothes hanging in it now,” Abigail pointed out. “I imagine it’s rather annoying to have to go through a lot of dresses and coats to get through to the other side.”

He ignored this unworthy statement. He was busy feeling along the back paneling of the wardrobe for the secret spring. “It’s stuck,” he said, annoyed. “Warped from the damp, I shouldn’t wonder. This never happens in books—the secret panel always slides back at the merest touch of the hero’s finger, with a sibilant hiss, I might add.” He stopped trying to force the panel open and looked at Abigail. “Give me a hand, will you?”

“Of course,” she said, without thinking. Cary doubted the girl had ever refused a direct request for help in her whole life. She was, in fact, such a nice girl in every way that, if he hadn’t been so sure that she was going to enjoy what he planned to do, he might not have done it. As soon as she was in the wardrobe with him, he pulled the door tightly closed, sealing them together in the darkness, pulled her close to him with both hands, while at the same time kissing her mouth. Even in the dark, his aim was true.

Abigail felt something warm and furry brushing against her mouth and went berserk. She burst out of the wardrobe, brushing away from her body wholly imaginary vermin. “Mr. Wayborn!” she gasped. “There is a bat—or a rat—in that wardrobe!”

Once or twice in Cary’s life, he had come across a female who, inexplicably enough, did not want to be kissed by him, but none of them had ever resorted to inventing small rodents.

“A rat or a bat,” he repeated sourly. “In the wardrobe, you say?”

Abigail jumped onto the bed, frantic for a place of safety. “I felt it touching my face, and then—oh, God! It moved.”

“There isn’t any bat,” he said sharply, now quite annoyed.

“There is too a bat,” she insisted, treading on the featherbed to keep from falling over. “It’s in that wardrobe, and I am not coming down from this bed until you find it and kill it!”

Cary began to believe she was serious, which did not improve his temper. No one had ever mistaken his kiss for the attentions of a small flying mammal, and his vanity was wounded. Grimly he climbed out of the wardrobe. “Stand still,” he told her angrily. “Close your eyes.”

Abigail obeyed. “Oh, God! Is it…Is it on me? Is it in my hair?” she whispered weakly.

“Quiet!” He climbed up on the bed next to her. For once she didn’t shy away from him. Very gently he took her by the shoulders and tried again, pressing his mouth to her clenched lips.

Abigail’s eyes popped open.

“It was not a bat, you silly girl,” he told her. “It was me. I was kissing you.”

“That’s it exactly. That horrid, furry feeling—” Abigail broke off, mortified. “I beg your pardon, sir!” she breathed. “I didn’t know it was you. You—you were talking about bats earlier at the Dower House. I’m absolutely terrified of bats, you see.”

He sniffed. “I had noticed a slight aversion.”

“I thought my heart was going to burst, it was beating so fast,” she said, climbing down from the bed. “I do hate them so.”

“What? Kisses or bats? I’m not often mistaken for a bat, cousin,” he said sharply. “I think you owe me an apology.”

“It—it must have been your beard I felt,” she explained, growing red in the face. “I’m so sorry, Mr. Wayborn. It’s just that it was dark, and I wasn’t expecting—” She broke off in confusion. It seemed to her, though perhaps she was wrong, that he was the one who ought to be apologizing. After all, she hadn’t given him leave to kiss her. She had never given anyone leave to kiss her in her whole life.

“You weren’t expecting it,” he scoffed. “Isn’t this what you came for?”

Abigail stared at him. “What?” she asked in a small voice.

“Why did you come to Hertfordshire? To see me again, that’s why. Admit it.”

Abigail gasped at the man’s unabashed conceit.

“I know when a woman is attracted to me,” he said. “You’ve been staring at me all afternoon. You stammer like an idiot whenever I get within two feet of you, and if your face got any redder, it would be a tomato.”

At this moment, Abigail liked Cary about as much as she liked Mrs. Spurgeon’s macaw. Indeed, Cato and Mr. Wayborn had a great deal in common. They were both physically beautiful and unforgivably rude. “I did not come here to see you again, you conceited ape,” she snapped. “You had a house to let. You obviously need the money. I was trying to help you. I had no idea of—of anything else. I thought you were safely married! I came here expecting to meet your wife. I did not expect to be mauled in a wardrobe.”

Cary shrugged. “It was only a kiss,” he said coolly. “A bit of fun. Most girls enjoy it.”

“I am not most girls!”

“Clearly.”

Absurdly, Abigail felt rejected. She turned away from him to look out the window. Her chin was going wobbly, and she knew she was about to cry.

“Who in the deuce let that dog up the stairs?” Cary muttered, just as Abigail became aware of a commotion in the hall. In the next moment, the corgi knocked the door open and bounded into the room, barking excitedly, followed closely by a servant girl carrying a jug.

“That wretched cur is not allowed upstairs, Polly,” Cary said severely. “He eats the plaster off the walls and hides marrow bones under all the pillows.”

“Yes, sir,” the girl said. “I’ve just come to build the fires, sir, and to tell you that the other carriage is stuck halfway up the drive in the snow. The lady says she can’t walk, sir. She wants to be carried up to the house in a chair. A sedan chair.”

Muttering under his breath, Cary left the room.

“I’m Polly, Miss,” said the servant, a sturdily built, blue-eyed lass with red cheeks. “I’ve brought you some hot water.” She set the steaming jug on the washstand and closed the doors of the empty wardrobe. “Whatever you do, Miss,” she said, giggling, “don’t let the master get you in the old press. He got me in there once and the next thing I knew, my skirts was over my head! Of course, he was only eleven at the time and hadn’t a clue what to do with me once he got me. I expect it’d be a different story now,” she added wistfully.

Abigail washed her face and hands, tuning out Polly’s chatter. She could not flatter herself into thinking Cary Wayborn had kissed her because of some powerful attraction; clearly, molesting young women was simply a matter of course with him. She wished she had never come here. Her hero, the gypsy prince who had rescued her in Piccadilly, was no hero at all.

Was there even a secret door, she wondered, leading through the wardrobe to the next room, or had that merely been a ploy to get her inside? When Polly was gone, she went into the wardrobe and felt along the back panel. When she pressed it at the top, it sprang back instantly.

With a sibilant hiss.