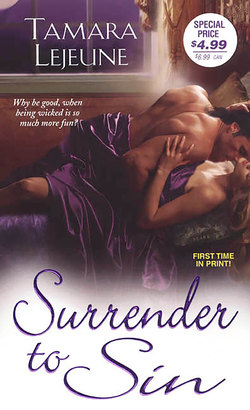

Читать книгу Surrender To Sin - Tamara Lejeune - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3

ОглавлениеWhen Abigail returned her engagement ring to Lord Dulwich, she expected a certain amount of private recrimination from the jilted man. To her surprise, he merely disappeared from her life. Abigail, who dreaded all unpleasant scenes, was immensely relieved.

The public uproar that followed, however, was worse than anything she could have imagined. The fact that her mother had been Lady Anne Wayborn was entirely forgotten, while it was discovered anew that her father, Mr. William “Red” Ritchie, was not a gentleman, but rather the reverse: a Glaswegian and a purveyor of Scotch whisky. For a woman of such imperfect descent to break her engagement to an English lord was tantamount to a peasant’s revolt, and, in the view of the Patronesses of Almack’s, deserving of punishment. This created some difficulty, for, as Lady Jersey dryly pointed out to Mrs. Burrell, Miss Ritchie could scarcely be cast out of all good society when she had never been permitted into it.

Lord Dulwich, meanwhile, was not immune to the scorn and ridicule of his peers, who openly despised him for having offered his ancient name to the Scotch heiress in the first place. His lordship retaliated by accusing Miss Ritchie of replacing the Rose de Mai, the carnation-pink diamond in her engagement ring, with a piece of worthless glass. In response to the accusation, Red Ritchie took the unusual step of purchasing twenty thousand pounds’ worth of loose diamonds from Mr. Grey in Bond Street, merely to demonstrate that Miss Ritchie could buy and sell a hundred Rose de Mai diamonds in an afternoon spree.

No one was surprised when legal briefs were filed in Doctor’s Commons. His lordship alleged that Miss Ritchie had stolen his diamond, and Red Ritchie filed suit for slander.

Abigail could scarcely venture out of doors without being pointed at and whispered over. People who would never have condescended to know her now went out of their way to give her the Cut Direct. Her uncle, Earl Wayborn himself, who had never communicated with Abigail in her life, not even upon the death of her mother, his elder sister, now petitioned to have the spelling of his family name legally changed from Wayborn to Weybourne in an effort to distance himself from the scandal.

Abigail went out less and less, and when Mr. Eldridge of Hatchard’s kindly began sending her the latest books, allowing her to choose what she wanted and send back the rest, she stopped going out completely. And yet, despite being a virtual exile in Kensington, she was dismayed when her father announced his intention of sending her into the country until the Dulwich affair was settled to his satisfaction.

The announcement came at dinner. Abigail set down her knife and fork with a clatter. “No, Papa,” she said, her quiet, genteel voice at odds with his Glaswegian brogue. “I’ve done nothing wrong. I refuse to be driven out of my home. I won’t leave you.”

Red’s mind was made up, however. “I’ve spoken already to Mr. Leighton. He agrees with me. It’s settled.”

Mr. Leighton was her father’s personal solicitor and would never have considered disagreeing with his most affluent client. Abigail was no more argumentative than Mr. Leighton; she knew argument would be futile. As long as she never asked for anything that did not coincide with his own wishes, Red Ritchie was an indulgent parent, but on the occasions when father and daughter disagreed, he gainsaid her ruthlessly.

“Please don’t send me to Aunt Elspeth in Glasgow,” she begged.

Fortunately, the tyrant had no idea of sending his only child farther afield than St. Albans or Tunbridge Wells. “You’re not going into exile,” he assured her. “I’ve asked Mr. Leighton to look for a suitable situation within easy distance to Town. Hertfordshire or Kent, I’m thinking.”

“Hertfordshire!” Abigail instantly thought of the handsome “cousin” who had come to her aid on the fateful day Lord Dulwich had so rudely bumped into her. She could now think of him without the crippling terror she had experienced at the actual time of their meeting. She had even begun to believe she could see him again without losing the power to think or speak intelligently. He had a house for rent in Hertfordshire. She would much rather stay in a cousin’s house than a stranger’s, and, of course, she would be absolutely delighted to meet his wife.

“We know no one in Hertfordshire,” Red Ritchie explained. “You’ll be called Miss Smith, and absolutely no one is to suspect that you’re my daughter, not even your chaperone.”

Abigail had some objections to the scheme. In particular, she doubted the efficacy of calling herself Miss Smith, but, having secured Hertfordshire as her haven, she was loathe to awaken the tyrant in her father by questioning his judgment. “And who is to be my chaperone?” she inquired pleasantly.

“Some auld woman of Leighton’s,” was the only answer forthcoming until Mr. Leighton himself arrived the next day with a portfolio of houses he deemed suitable for Abigail’s needs.

The proposed chaperone was revealed to be the mother of his first wife. A middle-aged widow, Mrs. Spurgeon was entirely dependent on Mr. Leighton, who was only ten years her junior. She had lived with the solicitor throughout his first marriage, and, after the death of her daughter, the arrangement had continued for reasons of simple economy. However, the introduction of a second Mrs. Leighton into the household had made necessary certain changes that had little to do with money. Mrs. Spurgeon and the second Mrs. Leighton cordially despised each other.

Abigail liked her father’s private solicitor enough to take his former mother-in-law from him without question, but, to her dismay, the portfolio he presented did not include a dower house attached to Tanglewood Manor. She brought the oversight to his attention.

“Tanglewood Manor,” he repeated thoughtfully. “An old college chum of mine is the Vicar at Tanglewood Green in Hertfordshire, Miss Abigail. There is nothing advertised, but I’ll make a private inquiry. Many of the best families prefer not to advertise, you know.”

Red Ritchie had left the choice of house entirely to his daughter, and so the matter was settled within a week. Red had but one demand, and, as long as Abigail promised to safeguard her health by drinking a quaich of Ritchie’s Gold Label every day she was away, she was free to do as she pleased in Hertfordshire, and Mr. Leighton was authorized to keep her in funds.

She could now look forward to making Mrs. Spurgeon’s acquaintance. On the way from Red’s Kensington mansion to his own modest town house in Baker Street, Mr. Leighton explained that his mother-in-law would be traveling with her latest nurse-companion. “Mrs. Nashe comes to us very highly recommended,” he assured Abigail. “The Countess of Inchmery was her most recent employer.”

“Is Mrs. Spurgeon ill?” Abigail inquired. “If so, Mr. Leighton, I wonder if it is advisable for us to remove her from London at this time of year.”

“She is not ill,” replied Mr. Leighton, his mouth tightening. “She has been examined by every doctor in London. She was ill, Miss Abigail…but it was quite four years ago. At that time, she so enjoyed the attentions of the young person I hired to wait on her that I believe she is determined never to be well again!

“She is a difficult woman,” he went on, “but, rest assured, you will not be expected to wait on her, Miss Abigail. I’ve made it clear that Miss Smith is the daughter of one of my clients, and most definitely not her servant. Her nurse and her maid will see to all her needs. Do not feel you must spend one instant in her company if you do not wish to.”

“I’m sure she’s not as bad as that, Mr. Leighton,” said Abigail mildly. “I would not mind in the least being useful to Mrs. Spurgeon.”

Mr. Leighton did not attempt to dissuade her from this view. Rather, he trusted that his mother-in-law would soon convince Abigail that he was speaking the gospel truth.

As they drove into Baker Street they found a scene of disarray. Mrs. Spurgeon herself was standing in the street directing the placement of what appeared to be the trousseau of a royal princess onto the baggage coach. Abigail’s chaperone was a massively built lady swathed in a billowing garment of the deepest black, but the overall impression she gave was of brute strength, not bereavement. Her face was a hard slab supported by more than one chin, and she had the cruel, dark eyes of a rapacious Mongol chieftain. If she had ever been pretty or young there was no sign of it now, except for a mass of bright yellow hair dressed in a style far too girlish for a stout woman of her years.

A woman of strict propriety, Mrs. Spurgeon refused to get into the private chaise as long as Abigail’s maid was in possession of it.

“If you are accustomed to traveling in the company of a servant, Miss Smith,” she bellowed in a voice a master of hounds might have coveted, “I am not. I suggest you put her in the second coach with the rest of the baggage. My standards will not be compromised simply because you do not know what is right.”

Abigail explained that Paggles had been her nurse when she was an infant, after having performed the same service to her mother before her. “Besides which, she is elderly and infirm,” she added, hoping to gain Mrs. Spurgeon’s sympathy.

While claiming to suffer from a variety of illnesses herself, Mrs. Spurgeon had no sympathy for fellow subscribers. “If she is too weak to travel with the baggage, then you had better turn her off. When my last maid wore herself out after only ten years, we sent her to the poorhouse. There she makes baskets out of reeds. A basket is a very useful thing, Miss Smith.”

Abigail was horrified. “Paggles will never be sent to the poorhouse, Mrs. Spurgeon!”

The lady stared at her. “I hope you don’t mean to pension her off, Miss Smith,” she said severely. “It is very bad for servants to be pensioned off. Is there anything worse than calling upon a new neighbor only to discover that it is, in fact, the pensioned-off dogsbody of a Cabinet Minister? I vow, it is getting to the point where they expect—nay, demand—to be granted a pension. The look Smithers gave me when I turned her off without a character, when it was the doddering old fool who dropped the tray—! Why should I, a poor widow, pay an annuity to someone who is of no further use to me?”

Paggles had grown frail in her old age; Mrs. Spurgeon’s clarion voice was enough to reduce her to tears. Though it was not in Abigail’s nature to court strife, she dearly wanted to rebuke Mrs. Spurgeon when Paggles clutched her arm in terror, wailing, “Please don’t let her send me to the poorhouse, Miss Abby! I’ll sit in the other carriage, if that’s what she wants.”

Abigail decided it would be cruel to force Paggles to remain in the chaise merely to satisfy her own urge to triumph over Mrs. Spurgeon. “No one is sending you to the poorhouse, darling,” she assured Paggles, as she helped her into the baggage coach. She gave Evans, Mrs. Spurgeon’s maid, a handful of shillings to look after the old woman.

Mrs. Spurgeon now assumed the chaise, and called for her birdcage. Abigail would not have objected to a collection of lovebirds, finches, or canaries, but when a servant brought forth a large brass cage containing a scarlet macaw with evil-looking claws and a monstrous beak, she became alarmed. Most parrots, in her experience, were well-behaved, but some sixth sense told her this one was trouble. “Oh, no,” involuntarily escaped from her lips, a reaction that seemed to please Mrs. Spurgeon.

“You must treat Cato exactly as you would an intelligent child, and say nothing before him you would not wish to have repeated, Miss Smith,” said she. “Some people find it disconcerting. But I believe that one should always guard one’s tongue.”

After no further delay, other than Mrs. Spurgeon’s being sure that Evans had forgotten the medicine chest, and Evans having to convince her that she had not forgotten the medicine chest, the chaise proceeded up Baker Street at a sedate pace, followed by the baggage coach.

With her considerable bulk and her parrot cage, Mrs. Spurgeon took up one side of the carriage, leaving Abigail to share the other seat with her nurse-companion. Mrs. Nashe proved to be an attractive young widow with the soft manners and speech of a true gentlewoman. Mrs. Spurgeon remained indifferent to any conversation between Miss Smith and Mrs. Nashe until the former complimented the latter’s clothes. Mrs. Spurgeon then felt obliged to inform Miss Smith that Mrs. Nashe’s smart clothes were all cast-offs from Lady Inchmery, a former employer. Needless to say, Mrs. Spurgeon did not approve of the practice of giving one’s clothing to one’s servants. In her opinion, it was nearly as bad as granting them pensions.

As they turned onto the Great North Road, Abigail proposed opening the curtains. There had been snow, and the countryside was bound to look like a winter wonderland in the morning sun. Mrs. Spurgeon, who certainly knew how to dampen youthful enthusiasm, curtly informed Miss Smith that views of rollicking countryside invariably caused her to vomit. Ditto the flickering of lamps. Therefore, the three ladies were obliged to sit in the carriage with the curtains closed and the lamps doused; Mrs. Spurgeon’s threat, though not quite believable to Abigail, was too horrible to be ignored.

Contented with the arrangements, Mrs. Spurgeon went to sleep, and her snoring was quite as stentorian as her speaking voice. “How do you bear it, Mrs. Nashe?” Abigail whispered.

“My husband was only a poor lieutenant,” the nurse-companion replied, pausing to squint in the darkness at her employer. A loud snore reassured her. “When he died of wounds he sustained at Ciudad Rodrigo, I was left destitute, to make my way as best I could. Mr. Leighton pays me very well, you see, and I have an elderly mother who depends on me for an income.” As she spoke, she caressed the simple gold band she wore on her left hand, and the expression of longing in her dark eyes would have melted the hardest of hearts.

“All the same, I could not do it,” said Abigail.

“She’s lonely and unhappy, Miss Smith,” Mrs. Nashe said gently. “I know what that’s like, you see. And, compared to my last situation, this is ideal.”

“Oh? Was her ladyship a harsh mistress?”

“The Countess was merely indolent, but her son, Lord Dulwich—!” Mrs. Nashe shuddered delicately. “When I left Cliffden, I felt I’d made a narrow escape.”

“Lord Dulwich!” cried Abigail. “He told me his mother was dead.”

Mrs. Nashe’s eyes widened. “Do you know his lordship, Miss Smith?”

Abigail blushed. “A little,” she said.

“I assure you both his parents are living. They are fine people, but the son is no credit to them. He’d take the most shocking liberties, then tell me if I ever complained to his mamma, she’d only turn me out of the house…which, of course, is exactly what happened. Her ladyship had some vestige of a conscience, however; she gave me a few clothes, and a very good letter which enabled me to find a place with Mr. Leighton. I’m happy to be where I am, Miss Smith. At least there are no men to molest me.”

“I’m very sorry for you, Mrs. Nashe.”

“Please do call me Vera—I can scarcely bear to be called Nashe. It reminds me of all that I have lost,” she said, dabbing her eyes with her handkerchief.

The reassuring snores abruptly ended, and the lonely and unhappy Mrs. Spurgeon banged on the roof with her stick until the coachman opened the panel. “Stop at the first inn you see,” she barked. “And do slow down, you fool! Your reckless driving is making me quite nauseous.”

“Slow down, you fool!” screeched her macaw, making Abigail jump.

The panel slid shut, and Mrs. Spurgeon suddenly confided to Abigail that her bladder was no bigger than a button. “We shall be obliged to stop at every half mile. Inconvenient, I know, but it can’t be helped.”

“Inconvenient” proved to be rather an optimistic view of things. At their fourth stop, Abigail looked longingly at the baggage coach as it went on ahead of them. Refreshed after a nap and a pot of tea, Mrs. Spurgeon proposed letting Cato loose in the carriage for the rest of the journey. Abigail objected in the most strenuous terms.

“You would not keep a child in a cage for two hours together, Miss Smith,” cried Mrs. Spurgeon, quite shocked by the young woman’s cruelty.

“I might,” said Abigail, rather tartly, “if the child had claws and a beak.”

“Claws and a beak! Beaks and claws!” screamed the macaw.

“There’s really nothing to be afraid of,” Mrs. Spurgeon said smugly, opening Cato’s cage and allowing the large bird to climb on her shoulder.

Abigail shuddered in revulsion. Cato had more in common with a small dragon than with the sweet little tame goldfinches she herself kept at home.

“Don’t worry,” Vera Nashe assured her. “I’ll give him a cuttlebone to chew.”

“Do please keep him on your side,” Abigail urged Mrs. Spurgeon, just as the scarlet macaw, sensing her fear, beat his wings and crossed the distance between them. His long gray talons closed on Abigail’s shoulder and his beak fastened on her ear. One icy blue eye peered into hers. “Claws and a beak!” he croaked.

Abigail screamed in terror, and Mrs. Nashe was obliged to rescue her.

Mrs. Spurgeon said repressively, “It’s really only a tiny amount of blood, Vera,” as Mrs. Nashe pressed her handkerchief to Abigail’s torn earlobe and Cato returned to his mistress.

Fortunately, Mrs. Spurgeon had not exaggerated the extreme smallness of her bladder. When the chaise stopped at the next inn on the Great North Road, Abigail quickly escaped. She was relieved to see the baggage coach standing in the yard. Without bidding her chaperone adieu, she sought refuge in it, unceremoniously knocking a bandbox from the seat next to Paggles, who opened her shawl and wrapped her young lady up in it. The scent of lavender, which had comforted Abigail since she was a child, soon lulled her to sleep in the swaying coach.

Evans woke her as they drew near the inn at Tanglewood Green. Paggles’s white head was resting on Abigail’s shoulder, and the young woman gently moved it aside to look out the window. Snow was falling thickly, and the sky was quite gray, but, despite this, the Tudor Rose was doing a roaring trade, judging by the amount of traffic.

“The river’s frozen ten feet thick,” the hostler explained to Abigail, who had not yet judged it safe to leave the carriage, “and all the young people do be skating on it.” The coach had driven across a broad stone bridge less than half a mile back, and Abigail guessed that the inn’s back garden went down to the banks of the same river. The Tudor Rose was a charming half-timbered building, and, had it not been so crowded, Abigail would have been glad to go in.

“Would you be wanting a hot cup of cider, love?” The hostler winked at her slyly, and Abigail realized the man must have mistaken her for a servant, not surprising as she was traveling with the baggage.

“No, thank you! Is Mr. Wayborn here to meet us?” she inquired from the window. “I am one of the new tenants for the Dower House.”

“The young squire’s been called away, miss,” he said more respectfully. “He waited for you all the morning. He left word for you to be looked after here. I can send a boy after him.”

A few young men were jostling about in the yard and one of them looked at her saucily. “It’s far too crowded for us to stay here,” Abigail said decisively. “I believe we must go on.”

“The young squire—” the hostler began.

“Mr. Wayborn would not expect you to argue with me,” said Abigail, feeling Paggles shivering. “It is out of the question for us to wait here in this noisy place, and if we do not leave now, the snow will keep us here overnight. Kindly tell the coachman the way to the Dower House. And we shall require another hot brick, if you please.”

When the boy brought the brick, Abigail herself tucked it under Paggles’s feet. Mrs. Spurgeon’s maid seemed amused that the young lady should lavish so much attention on her servant, but Abigail did not care if she appeared ridiculous. Paggles had been the only servant to stay with Lady Anne after her marriage to Red Ritchie, and she had always been more like a grandmother to Abigail than a lady’s maid.

The Dower House was not more than three quarters of a mile from the inn. As the coach rounded a bend of tall, ice-laden elms, Abigail looked out of the window. Her mouth fell open. The coach rolled to a stop.

“Good heavens!” Abigail cried in disbelief.

The house at the end of the drive was a handsome square cottage of rosy stone, half covered in ivy, exactly as it should be but for one thing. A very large elm tree had fallen on it recently, crushing the roof and upper attics of the left-hand side, and spraying shattered glass from the upper windows across the snow. A few men in frieze coats were standing about, shaking their heads over the mess, their breath freezing in the air.

“What is it, Miss Smith?” Evans wanted to know.

Without answering, Abigail flung open the carriage door and jumped out, forgetting in her haste to let down the step. She put her foot down, expecting to encounter something solid, then ended up falling nearly four feet down, landing in a heap in the snow.

“I believe it is customary for the lady to allow the gentleman to open the door for her,” said Cary Wayborn, helping her to her feet.

Abigail leaped at the sound of his voice, which she immediately recognized, and completely forgot about the elm that had fallen on the Dower House. She had been quite wrong in thinking she could see him again and remain rational. The sight of him and the nearness of him instantly shut down the best part of her brain. Her throat went dry and she could only stare at him helplessly. If she had been able to move, she would have run away from him, but her legs were rooted on the spot, and, besides, he was holding her hand. She was acutely aware that, despite the cold, he wasn’t wearing gloves, and his hand was quite as brown as his face. This was not how she had envisioned their second meeting.

Cary’s faith in his sister’s knowledge of London’s debutantes was so strong he did not doubt for a moment that he was looking at his Irish cousin, Miss Cosima Vaughn. While vain enough to believe she’d come to Hertfordshire in pursuit of him, the extreme boldness of the move puzzled him; he had judged her to be a young woman nearly crippled by shyness. Yet here she was, staring at him like a pole-axed doe with those oddly appealing light brown eyes.

“Good Lord,” he murmured aloud. “It is you, isn’t it? I’m not imagining things? You are my cousin from Piccadilly? Aged eleven and three quarters from the back, aged twenty-one from the front?” He began to smile at her, his eyes growing warm as the initial surprise of seeing her wore off. He was starved for female companionship in Hertfordshire, and he thought she might fill the void very nicely indeed. He might even succeed in discovering the scandal that had thus far eluded his inquisitive sister Juliet. Making her blush had already given him more pleasure than he’d had in a month. Better still, she was his cousin, and, as a blood relation, he could tease her and flirt with her as much as he liked, without arousing ugly gossip.

Abigail guessed he was the sort of man that made every woman he met feel special, and she tried to resist his smile. Sternly, she reminded herself that this was a married man.

“What brings you to Hertfordshire?” he asked politely, taking her hand.

Abigail began to stammer.

“Take your time,” he encouraged her. “I don’t mind the snow falling on me.”

She took a deep breath and expelled the words all at once. “You did say if I knew of anyone’s wanting a house.”

“But, surely you’re not Mrs. Spurgeon?” he said, startled.

“I’m traveling with Mrs. Spurgeon,” Abigail explained. She watched, fascinated, as a drop of blood trickled from Cary’s nose. It was rather like watching an archangel bleed.

Unaware he had sprung a leak, Cary looked into the coach and saw Paggles sleeping amongst the boxes. “Is that her?” he inquired in a low voice. “Why, she’s positively ancient.”

“She is my old nurse,” Abigail said, searching in her fox muff for a handkerchief. “Your nose is bleeding, sir.”

“I’m not a bit surprised,” he answered, taking out his own handkerchief to wipe his nose. “A carriage door banged into it quite recently.”

“Oh, no!” Abigail cried, unaware just how recently this mishap had occurred. “People ought to be more careful.”

“You’re quite right,” he agreed, holding his head back while applying pressure to his nose. “It was very careless of me to stand so close to the door.”

“Oh, I didn’t mean you, sir!” Abigail said, mortified that he should have misunderstood her. “It’s entirely the fault of the person in the carriage. He ought to have looked out first, before he flung open the door.”

“She, cousin.”

She fell silent, and when he brought his head down again, he noticed a telltale sheepishness in her eyes. “Does it hurt very much?” she asked, wincing in sympathy. “Really, I’m so dreadfully sorry. It’s just that I looked out the window and—and I saw the tree…”

“What tree?” he inquired politely, putting away his handkerchief. “I’ve a good few trees hanging about, in case you haven’t noticed. Was there one in particular that intrigued you?”

Abigail blinked at him in disbelief. “That tree, sir,” she said, pointing. “The elm.”

“Oh, that tree,” he said, indulging in what she thought a very odd sense of humor. “I was hoping you wouldn’t notice it was an elm. I’m quite bored with elms at the moment. I’ve been hearing stories about them all day. People who wouldn’t know an elm if one fell on their houses have suddenly become quite garrulous on the subject.”

“But it has fallen on your house, sir,” she stammered. “And it is an elm.”

“Yes, of course, it’s fallen on my house. Did you expect it to remain rooted in one spot forever and ever? We had an ice storm overnight, and the tree—pardon me, the Elm—lost its balance. Fortunately, my house was there to break its fall. The prevailing opinion is that it’s my fault entirely.”

Abigail frowned. “How can it be your fault if it was an ice storm?”

“Thank you for taking my part,” he said. “Apparently, the Elm was dead, and ought to have been cut down a year ago. Anyone could see it was going to fall over at the first gust of wind. By ‘anyone’ I mean, of course, everyone except me.”

“What on earth are you going to do?” Abigail asked.

“I say we ignore it,” he said, tenderly feeling the end of his nose. “Perhaps it will get tired and go away if we pay it no attention. I’ve a great many trees on the estate, and the vast majority of them are immensely well-behaved. Let us pay attention to them instead.”

“But where are we to go?” asked Abigail.

He raised his eyebrows. “Go? Don’t you like Hertfordshire?”

“We can’t possibly stay in the house now,” said Abigail, unnerved by his apparent unconcern. Her father was the only man she had ever really known, and, while neither quiet nor morose, verbal capers were not in Red’s line. Cary was so different that he baffled her.

“Don’t you like trees?” he teased. “They are generally thought to be pleasant things. Not that tree, of course. That is a very bad tree. But you mustn’t let it ruin all the good trees for you. Think of the shade they offer in the summer, the little birds who nest in their sheltering branches…” Reluctantly, Cary relented in the face of her utter bewilderment. Miss Vaughn evidently had no brothers; she was quite unaccustomed to being teased, which, naturally, made her irresistible to him. “Not to worry, cousin,” he said cheerfully. “I’ve a team of crack woodcutters on the case. You’ll be tucked in bed by nightfall.”

“What?” cried Abigail. “Even if they were able to clear it all away by tonight—which I doubt—we could not possibly sleep here. Why, half the roof is gone!”

“I’m only joking you, cousin,” he said, chuckling. “Of course you’ll have to stay at the Manor, provided the elms have not yet attacked it. It’s only half a mile across the field, nearly two miles by way of the road. I have my horse. I’ll take the shortcut and meet your coach at the house. I’ll tell your driver. Let’s get you back in the carriage before you freeze.”

“But, sir, we could not possibly—I mean, we could not stay in your house—”

“I don’t see why not,” he answered. “You were going to stay in that house and it’s mine. Or do you suppose it belongs to the tree now?”

“But the manor house,” Abigail persisted. “Is that not where you live, sir? I couldn’t possibly ask you to leave your home.”

“My dear girl, you couldn’t possibly ask me to share it,” he pointed out. “The Vicar in these parts happens to be my cousin, and he’s beastly strict.”

“Where will you go, sir?” Abigail asked.

He chuckled. “You needn’t look so forlorn. I shall only be as far away as the gatehouse. I’ll be honest with you, cousin,” he went on cheerfully. “I can’t give the rent back because I’ve spent it already. The desperate pity of it is, I spent quite a bit on the Dower House! Cleaning it, painting it, patching over the rat holes. Those chimneys hadn’t been swept since God was in short coats? You’d not believe the detritus that came down the flue in my lady’s bedchamber. Owls’ nests, and bats’ bones.”

“Bats!” breathed Abigail, searching the cold gray sky in dismay.

“Damned expensive, sweeps. The truth is, my dear cousin,” he added, taking her hand in his, “if you can’t convince Mrs. Spurgeon to take the Manor instead, I shall be ruined.”

“But you can’t ask your wife to remove to the gatehouse,” Abigail pointed out.

To her surprise, he laughed. “No, I don’t suppose I can.”

“I daresay the gatehouse would be adequate for our needs, sir,” said Abigail, rather doubtfully. “We are only three—Mrs. Spurgeon, Mrs. Spurgeon’s nurse, and myself.”

“Nurse? That settles it. Mrs. Spurgeon’s health will not permit her to be consigned to the inconveniences of the gatehouse. I shall take it, and leave you ladies to the comforts of Tanglewood Manor. No, I insist. I give you my word that my wife won’t object to the scheme. I expect Mrs. Wayborn to remain quite mute on the subject, as indeed, she is on every subject.”

Abigail stared at him. “Do you mean that your wife is a mute, sir?” she asked, shocked that he would joke about such a serious matter.

“She might be,” he carelessly answered. “I really don’t know.”

“How can you not know?” Abigail cried. “I don’t understand you, sir.”

“No,” he sadly agreed. “You’re not very good at riddles, are you? I’m not married, you see. But I daresay my wife is wandering about the earth in search of me as we speak, poor girl. She could be mute. She could be Irish, for all I know. I’m fairly certain she hasn’t got a hunchback or a mustache, but, then again, I’m such a spiritual fellow that her beautiful soul might be quite enough for me. She mightn’t even be born yet, though I must say, I find the thought of marrying a girl nearly thirty years my junior a bit daunting.”

“But of course you’re married,” Abigail argued. “I distinctly recall that you mentioned your wife to me. You said Mrs. Wayborn did all your reading for you.”

He raised his dark brows. “Did I? I seem to recall something along those lines. What I meant was that, when I do marry, she will have the job. Unless she should happen to be blind. I couldn’t ask it of a blind woman.”

“Then there is no Mrs. Wayborn to object to your living arrangements.”

“Not at present,” he qualified. “But if I know anything about my future wife—and I think I do—she wouldn’t object to staying with me in the gatehouse. As long as we two are together, her happiness will be complete. In any case, you must take the Manor.”

“Yes, of course,” Abigail agreed faintly as he let down the steps for her and helped her climb back into the coach. She felt utterly and completely stupid.