Читать книгу Bodies That Work - Tami Miyatsu - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеThe year of Frederick Douglass’s death, 1895, marked the beginning of a chaotic era in the history of racism against African Americans in U.S. politics.1 The ostensibly monolithic black discourse of anti-racism collapsed with the loss of this unyielding leader, orator, and statesman. That same year, Ida B. Wells—a possible heir to Douglass’s activism with her uncompromising commitment to social, political, and financial equality, regardless of race or gender—published a pamphlet titled “A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States, 1892–1893–1894.”2 In this thorough analysis of racial violence, she condemned the prevalence of lynching, stating that “no opportunity [was given to the victimized] to make a lawful defense” in a supposedly “civilized” nation.3 The antagonistic discourse she inspired, however, was soon replaced by the words of a newly emerging leader of African Americans—Booker T. Washington.4 In September 1895, Washington, who had a different strategy from Wells for resolving the institutional racism that African Americans had to incur, delivered an obsequious speech to the Cotton States and International Exposition, held in Atlanta, Georgia, that became widely known as the Atlanta Compromise.5 In the speech, he proposed a new solution to the problem of racism against African Americans in the United States. Despite criticism from fellow African Americans, such as W. E. B. Du Bois (another emerging black leader and scholar and a more ←1 | 2→aggressive spokesperson for black people), Washington’s speech received immediate national and international attention.6

Importantly, Washington’s speech subtly links U.S. prosperity to racial tolerance.7 He suggests reunion, instead of confrontation, for mutual benefit through the courtesy of “superior” whites.8 White people, he argues, had two options—either continuing to feel hostility toward African Americans or opting to build a new friendship with them. He repeated the phrase, “Cast down your bucket where you are,” shrewdly reminding the mixed audience of how much good or evil the hands of eight million black people could do:

Nearly sixteen millions of hands will aid you in pulling the load upward, or they will pull against you the load downward. We shall constitute one-third and more of the ignorance and crime of the South, or one-third to the business and industrial prosperity of the South, or we shall prove a veritable body or death, stagnating, depressing, retarding every effort to advance the body politic” [emphasis added].9

By using the term body politic—“an ancient metaphor by which a state, society, or church and its institutions are conceived as a biological (usually human) body,” as stated in Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (meaning a commonwealth or state)—Washington evoked clear images of the shared destiny of blacks and whites as the whole body of the nation.10

Washington’s metaphor of the nation as a unified, functioning entity echoes the rhetoric of John Winthrop, a British lawyer and leading figure in colonial America. In 1630, Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, stated that the American people should aspire to live in “a city upon a hill,” reminding them that “[t];he eyes of all people” were upon them.11 These two speeches, delivered by a white man and a black man living more than two and a half centuries apart, have similarities. First, Winthrop and Washington call for Christianity to be a force in nation (re)building. Winthrop stresses that Christian love will be “the bond of perfection” in the face of communal peril, whereas Washington describes the problem of racism against African Americans as “the great and intricate problem which God has laid at the doors of the South,” for which he proposed collaboration as the solution.12 Second, Winthrop and Washington invoke the image of a ship in distress to describe the failure to achieve Christian unity. In his speech, Washington compares the deadlock in race relations to a “ship lost at sea.”13 Winthrop notes, “Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck, and to provide for our posterity, is to follow the counsel of Micah, to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God.”14 Finally, Winthrop and Washington ←2 | 3→use corporeal images to symbolize the working nation. The two men only differed in the scale of the implied “body politic.” Winthrop referred to it as “one man,” using a metaphor of the church:

To instance in the most perfect of all bodies: Christ and his Church make one body. The several parts of this body considered apart before they were united, were as disproportionate and as much disordering as so many contrary qualities or elements, but when Christ comes, and by his spirit and love knits all these parts to himself and each to other, it [has] become the most perfect and best[-];proportioned body in the world. (Eph. 4:15–16)15

Winthrop calls for the collaboration of all of its parts, saying, “For this end [prosperity], we must be knit together, in this work, as one man.”16 By contrast, Washington compared the working nation to “fingers” on one big “hand.” He reportedly raised his “hand high above his head” with his “fingers stretched wide apart,” saying, “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”17 In his rhetoric, Washington indicates that slaves’ hands brought prosperity to the South for more than two and a half centuries—hands that sowed, plowed, picked, harvested, cleaned, cooked, raised, constructed, mended, undertook, and buried for “Massa” and his family in their servitude.18 Washington argues that friendship between the races would not harm white people because they would remain socially separate even if they collaborated for mutual prosperity. Using the metaphor of a struggle between the fingers, Washington warned of the possible financial loss that the country would incur if Americans cut some fingers off.

Washington’s body metaphor coincided with an increase in racial violence; he implicitly attacked “illegal” mob violence and demanded “willing obedience among all classes to the mandates of law.”19 According to a 1910 issue of The Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races—the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)—the known number of “colored men lynched without trial” peaked at 155 in 1892, totaling 2,425 from 1881 to 1910.20 During the time of slavery, enslaved Africans and their descendants had been treated as chattel, or pieces of property, and were considered valuable only when alive. Historian Stanley Elkins argues that it was virtually a non sequitur that a man would kill his own slave because, with a slave’s body being living “chattel,” no man would “destroy his own estate.”21 However, after slavery ended, the black body, alive or dead, became irrelevant to white people’s wealth. Sociologist Sarah A. Soule connects the increase in mob violence to socioeconomic competition and industrial growth because emancipated slaves and whites competed for jobs ←3 | 4→in the North and the South.22 As a powerful black leader from the time of his Atlanta speech in 1895 until his death in 1915, Washington attempted to reestablish African Americans’ value as free citizens and incorporate their bodies into the U.S. body politic as assets. He suggests a triple alliance of Northern capitalists, the white leadership class of a New South, and that African Americans should work together as a unified larger “hand” of America to increase the nation’s wealth.23

In the larger American body politic, a black body had been divided at the very beginning. In his essay “The Promised Body: Reflections on Canon in an Afro-American Context,” Houston Baker, Jr., maintains that the Founding Fathers, such as George Washington and James Madison, were concerned about slavery because it was “the semantic sign that marks [the] dimensions of the unnatural standing in direct contradiction to claims of an American natural”—the idea that an American is “a blessed human being endowed by Nature and Nature’s God with inalienable rights.”24 Nevertheless, they decided to incorporate the African body into unnatural slavery and the legislation by metaphorically dividing it into pieces. “In the language of the Constitution,” writes Baker, “the African body is fragmented into fifths, modeled into an object of trade, and subjected to immobile enslavement.”25 The dealing of an African body is thought to range up to 10 provisions, including this infamous three-fifths clause.26 A slave’s body was not in perfect shape, neither legally nor ideologically.

In Western political history, a body politic led by white males often lacked racial and gender perspectives.27 Although Washington’s body politic was based on a racial perspective, both his and Winthrop’s corporeal metaphors lacked references to gender because until 1920, the United States had denied women the right to vote—a minimum qualification for citizenship in a body politic.28 Because of the double barrier of race and gender to complete citizenship, African American women had the least political, social, and economic autonomy of any group in the United States.

In the American body politic, the black female body had been made invisible and was divided by proprietors. During slavery, the black female body was conceptually divided into parts: physical and mental, as well as religious and nonreligious. For instance, in Clotel; Or, The President’s Daughter (1853), a novel by William Wells Brown, a 16-year-old enslaved girl is assessed according to the value of all of her individual body parts, as well as her characteristics. The author describes how her total value ($1,500) was determined:

“Fifteen hundred dollars,” cried the auctioneer, and the maiden was struck for that sum. This was a Southern auction, at which the bones, muscles, sinews, ←4 | 5→blood, and nerves of a young lady of sixteen were sold for five hundred dollars; her moral character for two hundred; her improved intellect for one hundred; her Christianity for three hundred; and her chastity and virtue for four hundred dollars more.29

In this quote, Brown, a formerly enslaved writer, dramatizes the detailed process of turning a female body into a piece of merchandize. Speculators appraised the woman’s “chastity and virtue”—that is, whether her hymen was broken—in the same manner in which they assessed her other body parts. Thus, an enslaved woman’s body was metaphorically divided by slave traders, speculators, and customers, who collaborated to decide the accurate price of her whole body.

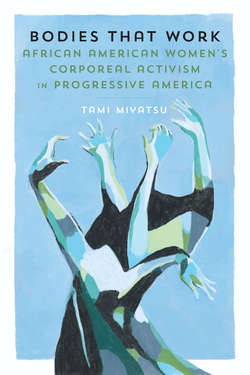

Bodies That Work describes the redefinition of such an invisible, fragmented, and commodified African American female body in early twentieth-century America. I argue that the four African American women examined in this book challenged the black female body’s social insignificance during and after the Progressive Era and provided alternative interpretations, such that it could become a substantial part of the larger body politic. These women are Sarah Breedlove Walker, entrepreneur of hair care products, also widely known as Madam C. J. Walker (1867–1919); E. Azalia Hackley (1867–1922), a soprano singer and musical organizer; Meta Warrick Fuller (1877–1968), one of the earliest female sculptors in the United States; and Josephine Baker (1906–1975), a St. Louis-born internationally famous singer and dancer. These inspirational, professional women attempted to integrate the divided body parts of African American women into one whole body by redefining themselves and by retrieving the autonomy of their material bodies—bodies that, under slavery, had been commodified, exploited, and stigmatized by the slave-owning South.

This project focuses on the several decades at the turn of the twentieth century—decades that correspond to both the Progressive Era and beyond—from the 1890s to the mid-1930s, as progressivism partly facilitated these African American women’s corporeal activism.30 In this era, the United States witnessed rapid industrialization, urbanization, and modernization, thereby forcing people to confront the consequences of these changes and further compelling them to address emerging social evils. Historian Alan Brinkley defines progressivism as “a protest by an aroused citizenry against the excessive power of urban bosses, corporate moguls, and corrupt elected officials.”31 Brinkley argues that progressives attempted to “restore order and stability to their turbulent society” through various reform initiatives—social, political, and spiritual.32 For instance, moral crusaders investigated the corruption of corporate moguls, labor union leaders, and government ←5 | 6→officials; muckrakers, such as Lincoln Steffens and Ida Tarbell, inflamed anger in their sensational exposé; and journalists and authors enthusiastically uncovered problems related to child labor, slums and ghettoes, prostitution, sexism, and racism.33 Notably, progressives embraced a naïve trust in the progress. The historian David Blanke asserts that “scientific” theories were rampant in the Progressive Era and that although American progressivism was “largely an optimistic faith in the ability of science and rational thought to address the worst abuses of modern life,” it paradoxically advanced traditional racial, ethnic, class, and gender prejudices.34 So flooded with changes, confusion, and disorder was progressive America that it allowed anyone and everyone with cause to challenge evils both old and new.

Progressivism also destabilized the hierarchies of race, class, and gender. In progressive America, African Americans became financially visible as wage earners, consumers, and business owners for the first time in American history. In Desegregating the Dollar, Robert E. Weems, Jr., observes that African Americans’ standards of living were much improved in the early twentieth century; the domestic labor shortage experienced during World War I allowed black people residing in the North to command higher salaries, and the Great Migration caused a similar labor shortage in the South, raising African Americans’ wages as a result.35 By 1920, some urban African American men and women in the North and in the South “had more money to spend than ever before,” participating in American capitalism as newly emerging consumers.36 They also emerged into the political spotlight, adapted themselves to modern American society through various routes that had previously been closed for them, and armed themselves with a strong voice and firm attitude toward opposing social injustice.37

In this rapidly changing society full of conflicting values, African American women also began to use their bodies (or body parts) in new ways and ventured into professions wherein they had typically not been represented before. These were bodies that worked—that is, laboring, functioning, and achieving in terms of collective empowerment. These black female bodies overcame racial, ethnic, class, and gender divides and negotiated with the ideas and values of political, financial, and intellectual leadership, dispelling the tenacious stereotypes of womanhood associated with slavery. Their work was not just physical but also cultural because their bodies created an interactive, interpretive space for women’s present and future agency. Work enabled black women to place their ostracized, stigmatized bodies into the larger body politic, demonstrating that they were worthier and more capable than previously thought and allowing them to assume roles with a higher value in the political and financial apparatus of the state. When African American women had been enslaved, they had been unpaid servants, ←6 | 7→cooks, babysitters, wet nurses, cleaners, and field hands and had been sexually abused in their roles as breeders and concubines. In progressive America, their bodies had agency—bodies earning money and creating value—which liberated them from the fetters of white male exploitation.

This book centers on the four African American women—Walker, Hackley, Fuller, and Baker—who distinguished themselves through their professions in response to the changing body politic. Their professions in the fields of entrepreneurship, music (opera), art (sculpture), and the performing arts (singing and dancing) were atypical of the generation of African American women whose parents were either legally or virtually in bondage. These women entered new professions that required physical work and reshaped the racial and gender division of labor. A “modern” society, full of contradictory perspectives and future uncertainties, assisted in the pursuit of their goals.

Scholarly research on African American women in the Progressive Era has long focused on stories of intellectual and middle-class women, particularly those involved in social reforms, mainly through printed documents. For instance, in Lifting as They Climb (1996; originally published in 1933), Elizabeth Lindsay Davis, calling herself “an ardent club woman,” describes how the black women’s club movement was enabled by middle-class women such as Mary Church Terrell and Fannie Barrier Williams, who taught black women practical skills, such as cooking, sewing, and the three Rs (reading, writing, and arithmetic), to prepare them for traditional roles and paid work.38 In When and Where I Enter (1984), Paula Giddings reconstructs the resistance stories of African American women and focuses on intellectual leaders, such as Ida. B. Wells, Anna Julia Cooper, and Mary McLeod Bethune.39 In Reconstructing Womanhood: The Emergence of the Afro-American Woman Novelist (1987), Hazel V. Carby also reinterprets black women’s “articulation of gender, race, and class” by referring to the works of literary women, such as Harriet A. Jacobs, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins.40 In the book Too Heavy a Load (1999), Deborah Gray White examines the role of black women’s collective, though not always monolithic, voice in national organizations in advancing their causes in the twentieth century.41 Karen Baker-Fletcher’s A Singing Something: Womanist Reflections on Anna Julia Cooper (1994) casts light on Cooper’s life and thought from a theological perspective, and Vivian May’s Anna Julia Cooper, Visionary Black Feminist (2007) also investigates previously unrecognized aspects of this feminist educator’s ideas, philosophies, and theories.42 These studies deal with written records of middle-class, educated (literary) female leaders and their intellectual activities that began in progressive America.

←7 | 8→

However, progressive black women’s efforts to enter into the mainstream were diverse, multifaceted, and physically oriented; because of racism, most of them engaged in physical labor as cooks, dressmakers, domestic workers, laundresses, and varieties of service jobs.43 Furthermore, in this era, some brave, gifted black women dared to enter professions other than those requiring traditional physical work, breaking through racial and gender barriers by using their bodies in unconventional ways—work that would reshape and destabilize the social hierarchy that placed nonwhite women at the bottom of society. Therefore, to outline African American women’s layered activism, we must listen to the voices of physical laborers who lived through the change in the United States in the early twentieth century.

As the body affects the decision-making occurring at every moment in our lives, Bodies That Work concentrates on our material human body. The body has often been ignored in the sociopolitical discourse, although it internalizes, reflects, and forms life as we know it. As Karl Marx asserts, the human body is the source of the social self, and history premises itself on “human existence”:

The first premise of all human history is, of course, the existence of living human individuals. Thus the first fact to be established is the physical organization of these individuals and their consequent relation to the rest of nature. Of course, we cannot here go either into the actual physical nature of man, or into the natural conditions in which man finds himself—geological, hydrographical, climatic and so on. The writing of history must always set out from these natural bases and their modification in the course of history through the action of men.44

“Life is not determined by consciousness,” says Marx, “but consciousness by life.”45 All social and political thoughts start with our daily struggle to survive. In this struggle for survival, we work (earn) to sustain our physical bodies, which require food, air, water, clothing, and shelter. Just as people do today, progressive African American women sought the materialization of their wishes, goals, and ambitions through physical labor.

Moreover, the body bridges our consciousness and the world. As French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty notes, the body objectifies and subjectifies our surrounding:

We must discover the origin of the object at the very center of our experience; we must describe the emergence of being and we must understand how, paradoxically, there is for us an in-itself …. And since the genesis of the objective body is only a moment in the constitution of the object, the body, by withdrawing from the objective world, will carry with it the intentional threads linking it to ←8 | 9→its surrounding and finally reveal to us the perceiving subject as the perceived world.46

Each life decision is often tied to a perception of how our bodies work or fail. In nature or society, our daily perceived sense of successes and failures incessantly determines how we use our bodies. In this sense, history is a perceptual accumulation of human corporeal feats and defeats.

With the recent rise in the interest of body studies, the body, to borrow Margo DeMello’s expression, has come to serve as “a full-blown site for cultural war.”47 The body has been problematized by feminists, historians, sociologists, and anthropologists, whose work has continuously revised the definition, role, function, meaning, and ideology of the body—especially the female body. In Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (1993), feminist philosopher Judith Butler investigates how the body is constructed through the performativity of sex and sexuality—or “the workings of heterosexual hegemony.”48 In Fasting Girls: The History of Anorexia Nervosa (1988), historian Joan Jacobs Brumberg explores how women historically “use[d]; their appetite as a form of expression” to acquire the ideal body shape long before the modern entry of the disease “anorexia.”49 In Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body (1993), Susan Bordo focuses on the continuing cultural reproduction of masculinism in public institutions, which reduces women to their bodies, whose depictions in Western philosophy are generally negative: “[t]he body as [an] animal, as appetite, as [a] deceiver, as [a] prison of the soul and confounder of its projects.”50 In The Woman in the Body: A Cultural Analysis of Reproduction (1987), anthropologist Emily Martin demonstrates how women’s bodies have been treated as “mechanical factories or centralized production systems” in medical texts.51 These works examine how Western society has stigmatized and politicized the female body.

This research contributes to body studies and pursues the interrelationship between the individual female body and the body politic by zeroing in on body parts (or organs) as the source of racialized and gendered resistance. Each chapter in this study addresses the redefinition of a female body part because, as suggested earlier, the body of black women has historically been divided, stigmatized, and assessed in terms of its parts. The parts of the body examined in this book include black women’s hair, vocal cords, wombs, and torsos (the naked body), all of which were devalued, dishonored, and made dysfunctional by slave traders and slave owners. Although some body parts may appear insignificant in a metaphysical body politic, these parts nevertheless reshaped African American women’s self-image and renewed their views of American society. As breadwinners, consumers, ←9 | 10→artists, and creators, as well as full citizens of capitalist America, they altered the public perception of the black female body by redefining its parts. Their corporeal activism began with individual body parts and proceeded to address the whole body. Although they adeptly avoided confrontation with patriarchy, they articulated, advocated, and embodied antiracist, feminist stands and challenged white cultural norms.

Through the analytical and interpretive reading of texts and images, Bodies That Work investigates African American women’s corporeal activism during the Progressive Era (the 1890s to the 1920s) and beyond. The book blends an application of archival and interpretive approaches to various kinds of materials, such as personal notes, letters, artwork, movies, stage productions, articles in periodicals, advertisements, and related textual and contextual documents. These records and writings, including exchanges between the women and their correspondents, promise to shed light on women’s politicized bodies at the macro and micro levels.

Chapter 1 examines the work of Sarah Breedlove Walker, better known as Madam C. J. Walker, as seen in her advertisements, letters, newspaper articles, and beauty schools’ student manual. Walker transformed black women’s stigmatized hair into a source of pride and a locus of resistance by devising a formula, or a grammar of beauty culture, to empower black women in the United States and abroad. This chapter focuses on Walker’s hair culture and cultural work, which helped black women embrace their bodies and improve their quality of life. The chapter unveils how Walker’s grammar of beauty culture was formed, spread among women across the United States and beyond, and became a means of confronting and surviving racism in progressive America.

Chapter 2 focuses on E. Azalia Hackley’s musical mobilization to find out why and how she inspired black Americans by employing the vocal organ. Hackley, often called “Madame Hackley,” was an African American soprano singer and vocal trainer who studied classical Western singing in Paris and London. She is better known to literary critics and historians as the author of a book of manners for black girls, The Colored Girl Beautiful (1916). However, despite her image as a representative of establishment values, Hackley was in fact a grassroots social activist who toured during most of her professional years, inspiring thousands of people through her vocal cords and organizing large musical events throughout the nation. Without belonging to any organization, she provided fertile ground for African American musical geniuses, such as Marian Anderson and Roland Hayes, to earn fame. This chapter is first concerned with the meaning of spirituals—songs she helped revive among African Americans—sung at the community recitals she directed in churches and schools throughout the country. The ←10 | 11→chapter then explores the impact of her seemingly apolitical missionary work on progressive African Americans living under the Black Codes (commonly referred to as “Jim Crow” laws), a revised version of the Slave Codes.

Chapter 3 analyzes African American sculptor Meta Warrick Fuller’s redefinition of the black woman’s womb in her mother–child sculpture, In Memory of Mary Turner: A Silent Protest Against Mob Violence. Mary Turner was an African American woman who was brutally lynched by a mob that mutilated her womb, removed and crushed her fetus, and burned her alive. The incident gave Fuller the impetus to create a permanent expression of her opposition to the inhumanity of mob violence. This chapter describes how the incident represented white patriarchal dominance over black women’s wombs during and after slavery and explores how Fuller’s statue addressed racial and gender prejudices and demanded African American women’s reproductive autonomy in progressive America.

Finally, Chapter 4 discusses how the nudity (the bare-breasted torso) of Josephine Baker, an African American performer based in Paris, confronted white racist images in the 1920s and 1930s. After leading a life of quasi-slavery in the United States, Baker sailed to France in 1925, settled in Paris, capitalized on French primitivism, and successfully entered the French body politic. Her manipulation of opposing images—savagery and civility—allowed her to blur her racial origin, join the French social elite, and rise above controversies over French colonialism. This chapter examines the hidden cultural implications of her female nudity on both sides of the Atlantic by interpreting her nude body as a performance costume. It then explores how Baker’s self-chosen nudity created a counter-narrative to American racism and changed the stereotyped image of the black woman.

My study focuses on women’s working, money-making bodies and body parts because I view economic strength as an underlying motivator for these women’s transformative work. Their financial independence empowered them to address racism because, as economic historian Karl Polanyi notes in The Great Transformation, “man’s economy, as a rule, is submerged in his social relationships.”52 “Instead of economy being embedded in social relations,” says Polanyi, “social relations are embedded in the economic system.”53 Despite, or perhaps thanks to, the double prejudices of race and gender hindering African American women’s participation in the mainstream economy, they were more active in pursuing entrepreneurial, independent careers than their male counterparts. While many African American men were involved in agricultural work, black women “developed entrepreneurial niches” in dressmaking, hair care, and other personal services, such as boarding houses, restaurants, midwifery, and education, in the early twentieth century.54 The four women in this book also ventured into new ←11 | 12→professions that enabled them to make a breakthrough into the veritable body politic. Their pioneering work gained (inter)national recognition because their bodies created something new, unique, or otherwise valuable to people at the time. As I explain in the following chapters, these women’s revisions of female body parts through professional work were shared among African American women and altered their appearance, behavior, demeanor, visions, and goals, helping them to rise out of lives of oppression and submission.