Читать книгу Walking on the West Pennine Moors - Terry Marsh - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The West Pennine Moors, located between the towns of Chorley, Bolton, Horwich, Ramsbottom, Haslingden, Oswaldtwistle and Darwen, comprise 233km2 (90 square miles) of moorland and reservoir scenery. The area has been a place of recreation for many generations of Lancashire folk; indeed, long before the much-vaunted mass trespass on Kinder Scout, there were organised trespasses in the late 1800s (small and large: around 10,000 people in 1896) and court proceedings on both Winter Hill and Darwen Moor in an attempt to keep rights of way across the moors open. The West Pennine Moors were very much in the vanguard of the campaign for access to our countryside, not that you’ll find many so-called authoritative texts on the matter admitting as much. But the facts speak for themselves; it happened here first.

Dissected by wooded cloughs and characterised by skyline features like Rivington Pike, the Peel Monument on Holcombe Moor and Jubilee Tower (also known as Darwen Tower) on Darwen Moor, the moors are a highly valued and much-appreciated region for recreation and study. Almost the entire area is water catchment, and the successor to the North West Water Authority, United Utilities, owns around 40 per cent of the land, and operates four information centres – at Rivington, Jumbles Country Park, Roddlesworth and Clough Head, Haslingden Grane, which also offer refreshment facilities.

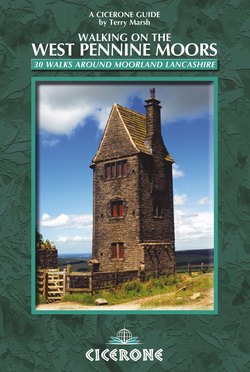

Darwen Tower (Walk 14)

The summit of Cheetham Close (Walk 24)

For the walker, the area has much to offer. This is gritstone country, and the landscape is often dark and sombre as a result. And there is a clue in its use as a water catchment area; in all but the driest of climatic periods, it is wet, boggy and invariably muddy. This might lead you to suppose that it is unappetising, unappealing and unattractive. But nothing could be further from the truth. This is a beautiful, semi-primeval landscape, a moorland theatre of considerable appeal and attraction, and a superb canvas for interests in flora, fauna, biology – even the modern leisure pursuit of geocaching. Come here at any time of year, and you will find others doing the same. The West Pennine Moors are a rich and varied playground for the walker, giving pleasure throughout the year.

Geography and Natural History

Rising to a peak on Winter Hill (456m/1496ft), the area is predominantly upland, with myriad well- trodden paths and areas of historical and geological significance. Although a large area of moorland became freely accessible under the right-to-roam legislation introduced by the Countryside and Rights of Way Act (2000) much of the terrain is marshy and difficult walking, and the footpaths – of which there are a great many – generally remain the most convenient means of access.

The moorland occurs in fairly well-defined blocks – at Withnell, Anglezarke and Rivington Moors; Darwen and Turton Moors; and Oswaldtwistle and Holcombe Moors, where the prevalent land use is sheep farming. Unlike other areas of moorland in the north of England, the West Pennine Moors are not managed for grouse shooting (not for want of trying), and are characterised by rough grassland and peat bog. This is one of the reasons why the moors never suffered the same degree of ‘access aggravation’ that occurred further south, in the Peak District.

Providing useful habitat areas for wildlife, the West Pennine Moors are bisected by a number of wooded valleys and cloughs, the largest being the Roddlesworth valley, near Tockholes. Although there are some small coniferous plantations, particularly around the reservoirs, the woodland cover overall is nominal, and it is a fine sense of openness that dominates here, and this, coupled with the intricate network of footpaths, makes the area an ideal place to begin a lifetime of recreational walking and to practice the necessary skills of map reading and navigation.

The main valleys are consumed by large reservoirs constructed in the mid- to late 19th century to supply water for Lancashire’s urban population. Evidence of this Victorian landscape is found in the form of mixed woodlands, styles of architecture and dressed stone walls. Along the valleys, the landscape is characterised by farmland pasture and meadows enclosed by drystone walls, built from the sombre gritstone that pervades great parts of the moorland area. Species-rich grassland is restricted in both area and distribution, mostly to steeper valleys or cloughs.

Approaching White Coppice (Walk 6)

It’s worth keeping your eyes open in the woodlands…

The valleys are very rural in character, with large areas of grazing land and broadleaved woodland and plantations, notably around Roddlesworth and the Turton and Entwistle reservoirs, which enable them to absorb high numbers of recreational visitors without feeling overcrowded. It is a curious paradox: you may always be able to see someone, or a farm or villages, but yet feel very isolated up on the moors. Although native broadleaved woodland is a habitat restricted almost entirely to valleys, there are fine examples of oak woodland, ash woodland, and wet woodland dominated by alder or willow, such as at Longworth Clough SSSI.

Plantlife

The West Pennine Moors area is recognised as a Core Biodiversity Resource at both regional and sub-regional levels, supporting a range of UK Priority Habitats and Species. The moors and farmland that surround and meld with the West Pennine Moors have a high level of biodiversity. Where the moors are unenclosed, there are widespread areas of blanket bog on deep peat soils.

Repeatedly modified by grazing, burning and attempts at drainage, the moors are in places dominated by purple moor-grass, along with distinctive species such as cotton-grass, heather, cross-leaved heath, cranberry and numerous species of sphagnum moss, as well as less prevalent plants like bog rosemary. Elsewhere there are rolling areas of upland heath, acidic grassland and upland flushes.

The extensive hill peat is of considerable importance for preserved plant and animal remains, and as a means of providing information about past climates and weather patterns. Most importantly, it has a significant role in future carbon dioxide sequestration to mitigate climate change, and in water catchment.

Birdlife

Ornithologically, all of the reservoirs, especially Jumbles, Wayoh, Delph, Belmont and Rivington, are important to wintering wildfowl. Belmont is also significant for the breeding waders associated with the adjacent in-bye pastures. The woodlands and plantations are valuable for breeding birds, including woodcock, redstart and pied flycatcher.

Moorland birds include peregrine, merlin, dunlin, wheatear, snipe, short-eared owl, golden plover, kestrel, buzzard, and an occasional sparrowhawk. Some of the more improved pastures still retain populations of breeding wading birds, such as lapwing and curlew, and particularly in the fields and margins around Belmont Reservoir there are often large groups of oystercatcher, redshank and sandpiper. The reservoir itself has nationally important populations of black-headed gull.

Human Influence

The cultural heritage of the area is of similar significance, stretching from Neolithic times to the remains of 18th and 19th century industrial and farming activities – such as mines and quarries, field systems and abandoned farmsteads. Evidence of pre-industrial use shows itself in field patterns on the lower valley sides, abandoned farmsteads, and buildings like the medieval manor house at Turton. However the construction of the reservoirs and pre-reservoir mining has destroyed many early remains of land use and settlement. Evidence of later settlement is widespread throughout the valleys, for example near Anglezarke where there are remnants of 18th- century lead mines.

The cotton industry was well established in Lancashire by the 1750s. Cotton goods imported from India were highly fashionable and very expensive, so there was a demand for a cheaper alternative. By the 1840s handloom weaving was in decline, but Lancashire had some important advantages as mechanisation increased. It was close to sources of cheap coal, and to the manufacturers of machinery in Oldham and Manchester. In addition, Liverpool was the primary port in the UK for importing cotton from the Americas.

As the Industrial Revolution progressed, so the local population increased, and in the 19th century the landscape was transformed by the construction of large water bodies to supply the surrounding conurbations. The reservoirs represent major feats of engineering and construction, and are of considerable historical significance. Victorian detailing of the built features of the reservoirs – Gothic-style valve towers and crenellated stone walls with decorative reliefs, for example – are important architectural heritage.

The Witton Weavers Way

In Victorian times, Lancashire was the centre of the cotton industry, and mill towns like Blackburn and Darwen, very much at the heart of the West Pennine Moors, were known across the world. Before the Industrial Revolution, however, handloom weavers worked from home, from the lovely stone-built cottages that still serve as the nucleus of many of the Lancashire villages and hamlets.

The Witton Weavers Way is a 51km (32-mile) trail around the industrial uplands of Lancashire – a commemoration, if you like, of those past times. It is a journey that leads past many of those ancient cottages, Tudor halls, Victorian estates, business-like villages and even Roman roads.

The full Witton Weavers Way can be completed in two days, but within its journey there are also four shorter circular walks that can each be covered in a day. Named after jobs within the cotton industry, these are the Beamers (10km/6 miles), Reelers (12km/7½ miles), Tacklers (15km/9½ miles) and Warpers (13.5km/8½ miles) Trails. Many of the walks in this book encounter or use stretches of these individual walks, and all are waymarked.

On the Witton Weavers’ Way, Turton Heights (Walk 22)

The official starting point is Witton Country Park, on the outskirts of Blackburn, but the Way can be joined at many alternative points. Full details of the individual walks, along with route descriptions, are available from www.blackburn.gov.uk.

Introducing the Valleys

Rivington

This wide, shallow valley is largely water-filled and contains three reservoirs: Anglezarke, Upper and Lower Rivington, and Yarrow. Built by Liverpool Corporation in the mid-19th century, these reservoirs cover the courses of three separate streams. Much of the character of the lower part of the valley owes its influence to Lord Leverhulme, who had his home at Rivington Hall. His keen interest in architecture and landscape design permeates the valley in the form of long, tree-lined avenues, a network of footpaths, the Rivington Terraced Gardens, and a replica of the ruins of Liverpool Castle on the banks of Lower Rivington Reservoir. The landscape of Lever Park now forms part of Rivington County Park.

Turton-Jumbles

This valley to the north of Bolton contains a line of three smaller reservoirs surrounded by woodland, mainly in the form of conifer plantations. Originally the valleys fed Bradshaw Brook, a focal point of industrial activity based on textiles. Entwistle was the first to be built, in the 1830s, one of the first reservoirs in the country of such size, followed by Wayoh in the 1860s, and Jumbles in 1971. The reservoirs are now a focus for recreation and nature conservation, with walking, fishing and other leisure pursuits located at Entwistle and Wayoh, and the county park centred around Jumbles.

Haslingden Grane

The Grane valley, to the west of the town of Haslingden, is remote. It is occupied by three reservoirs: Calf Hey, Ogden and Holden Wood, while the valley sides contain a mix of coniferous and broadleaved plantations and open pastures. This was once a well-populated valley, with farmers, quarry workers and a number of mills. The entire valley was depopulated when the reservoirs were constructed. Today, the scattered abandoned farmsteads, ruined cottages, pastures and packhorse tracks are remnants of the pre-reservoir landscape. The Grane valley, flanked by rather steeper sides than the other valleys, is especially appealing, and increasingly used for informal recreation.

Belmont

The Belmont, Delph, Springs, Dingle and Wards reservoirs are sited in an incised valley high above Bolton. The village of Belmont, on the route of the A675, forms a focus for this area, and despite the presence of settlement, this is a quiet valley. There are numerous public footpaths, many linked to form the Witton Weavers Way, a walking trail of discovery around the moors (see Human Influence).

Higher Hempshaw’s Farm (Walk 6)

Belmont from Sharples Higher End (Walk 16)

This valley is more rural than the others; ancient woodland still clings to the steep cloughs that have not been dammed. These also contain important wetland habitats. Belmont is one of the earliest recorded settlements in this area, dating from the early part of the 13th century (recorded in 1212), and later found itself situated along the turnpike road linking Bolton and Preston.

Roddlesworth

The Roddlesworth and Rake Brook reservoirs sit in an extensively wooded valley of mixed plantations above the towns of Blackburn and Darwen. A number of footpaths pass through the valley, and roads pass either side of it. It is a quiet and remote landscape dominated by reservoirs.

One of the beauties of the West Pennine Moors is that they are accessible. There are towns, villages and roads everywhere, making access to the moors as easy as could be. Many parts of the area are managed specifically for walkers, especially those parts around the reservoirs.

There are few, if any, other places in Britain that provide such a wealth of walking potential for so many, so easily. Make the most of it.

Earnsdale Reservoir and Darwen Tower (Walk 13)

Walking Safely

The walking on the West Pennine Moors ranges from short, simple outings not far from civilisation, to tough moorland routes. The many valley walks are within the ability of anyone accustomed to recreational walking. The longer walks on the moors, however, demand a good level of fitness, and knowledge of the techniques and requirements necessary to travel safely in wild countryside in very changeable weather conditions, including the ability to use map and compass properly.

Safety

The fundamentals of safety in upland and moorland areas should be known by everyone intent on walking on the West Pennine Moors, but no apology is made for reiterating some basic dos and don’ts.

Always take the basic minimum kit: sturdy boots, warm, windproof clothing, waterproofs (including overtrousers), hat or balaclava, gloves or mittens, spare clothing, maps, compass, whistle, survival bag, emergency rations, first aid kit, food and drink for the day, all carried in a suitable rucksack.

Let someone know where you are going.

Learn to use a map and compass effectively.

Make sure you know how to get a local weather forecast (see www.bbc.co.uk/weather).

Know basic first aid – your knowledge could save a life.

Plan your route according to your ability, and be honest about your ability and expertise.

Never be afraid to turn back.

Be aware of your surroundings – keep an eye on the weather, your companions, and other people.

Take extra care during descents, even gentle ones.

Be winter-wise – if snow lies across or near your intended route, take an ice axe (and know how to use it properly).

Have some idea of emergency procedures. As a minimum, from any point in your walk, you should know the quickest way to a telephone. You should also know something of the causes and treatment of, and ways of avoiding, hypothermia.

Respect the moorland environment – be conservation minded.

Using this Guide

Each walk description begins with a short introduction, and provides start and finish points, as well as a calculation of the distance and ascent. The walks are grouped largely within the traditional areas of the moors.

Distances

Distances are given in kilometres (and miles), and represent the total distance for the described walk, that is, from the starting point to the finishing point.

High Bullough Reservoir (Walk 9)

Ascent

The figures given for ascent represent the total height gain for the complete walk. They are given in metres (and feet, rounded up or down).

This combination of distance and ascent should permit each walker to calculate roughly how long each walk will take, using whatever method – Naismith’s Rule (see below) or another that you find works for you. On the West Pennine Moors, however, allowance must be made for the ruggedness of the terrain.

Naismith’s Rule

The ‘time allowance’ given in a guidebook provides a useful approximation, but it does no harm to work things out for yourself. ‘Naismith’s Rule’ is a useful method of working out an individual estimate:

allow 1 hour for every 5km (3 miles) of distance

add half an hour for each 300m (1000ft) of height gain.

Note ‘Height gain’ and ‘ascent’ are potentially confusing. Height gain is the amount of height you have to climb on a walk, and is the sum total of all the up sections, not just the difference between the starting point and the top of the mountain.

The diagram illustrates the point. Height gain is the sum of the height difference at each of the three points A, B and C.

Naismith’s Rule has been in use for years and is a good guide, but it is a worth keeping notes over a period of a few months and assessing the time your walks actually took against Naismith’s calculation. You may find that you are 10 per cent faster than Naismith, or 15 per cent slower. The value of this is that you can then apply Naismith’s Rule to your walks, and make an adjustment for your personal abilities.

Maps

1:50000 – all the walks in this book can be found on Ordnance Survey Landranger Sheets 103 (Blackburn and Burnley), and 109 (Manchester).

1:25000 – of greater use to walkers on the West Pennine Moors is the Ordnance Survey Explorer Sheet 287 (www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk), which covers all the walks in this book.

Paths

Not all the paths described in the text appear on maps, and where they do there is no guarantee that they still exist, or remain continuous or well defined. With only a small number of exceptions, paths are signposted, but not always waymarked.