Читать книгу The Isle of Skye - Terry Marsh - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Lovest thou mountains great,

Peaks to the clouds that soar,

Corrie and fell where eagles dwell,

And cataracts dash evermore?

Lovest thou green grassy glades,

By the sunshine sweetly kist,

Murmuring waves and echoing caves?

Then go to the Isle of Mist!

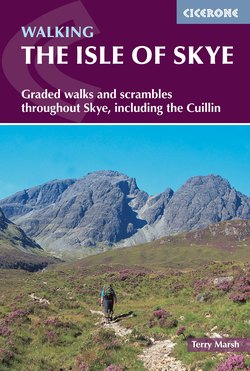

Bla Bheinn group from Strath Suardal (Walks 2.5 and 2.6)

Described by the then Duke of York (later King George VI) during a visit in 1933, as ‘the isle of kind and loyal hearts’, Eilean a’Cheo, the Isle of Mist, is second in size only to the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. It is known also as An t-Eilean Sgiathanach, the Winged Isle, because it can be viewed as a mighty bird with outstretched pinions, coming in to land, or to seize upon prey. Such has been the influence of Skye on the senses of visitors since the first tourists came to the Island that it has also assumed other names, all equally valid: the Isle of Enchantment, the Isle of Mystery, the Isle of Fantasy. To the Islanders, it is simply the Island, with a capital ‘I’, one of many islands; but to those for whom the Island is home, there is no comparison, no equal, no thought even that there might be.

By raven, Skye extends 78km (49 miles) from Rubha Hunish to the Point of Sleat, and if you travelled in a straight line overland from east to west you would cover 43km (27 miles). Yet such is the irregularity of the Island’s coastline, probed by many fjord-like lochs, that you are rarely far from the sea, and never more than 8km (5 miles).

One of the earliest descriptions of Skye appeared in 1549, when Dean Munro wrote: ‘The iyle is callit by the Erishe, Ellan Skyane, that is to say in English, the Wingitt ile, be reason it has maney wings and points lyand furth frae it through the devyding of thir lochs.’

The original derivation of the Island’s name is lost, but many hold that it comes from Sgiath, the Norwegian for ‘wing’, while others contend it derives from another Norwegian word ‘ski’, meaning a mist, hence ‘The Misty Isle’.

Setting aside these fundamental controversies of nomenclature, which merely serve to spark the flame of Skye’s inordinate appeal, the Island is the most popular of all islands among tourists, mountaineers and walkers: botanists, photographers, natural history observers, too, find endless fascination within the bounds of Skye’s ragged coastline.

The Coral Beach (Walk 4.11)

Visiting walkers inevitably head for the Black Cuillin, unquestionably the most magnificent mountain group in Britain, yet there is so much more to Skye, and walking places, coastal and inland, are a perfect balance to the weight of the Cuillin. The most obvious of all the mountains on the Island are the Red Hills since the main road across the Island skirts around them. Once these are passed, however, you come into view of the Black Cuillin, a stark, jagged skyline that boldly impresses itself on the memory, yet when the cloud is down, they can be missed altogether. The contrast between the two Cuillin is remarkable: from a distance the Black Cuillin look like just one elongated mountain with a serrated edge, a badly formed saw, if you like. The Red Cuillin, on the other hand, are smooth-sided, generally singular and distinctive mountains. There is no danger of mistaking the two.

The Island can be compartmentalised, as it has for this guide, into districts. Most southerly is Sleat, though this is strictly an old parish name. Sleat abuts Strath, which extends northwards and west to the major promontories of the Island – Minginish (which embraces the Cuillin), Duirinish, Waternish and Trotternish. The ‘nish’ ending is of Norse derivation, and means promontory.

The Red Hills and the Cuillin Outliers lie within Strath, and more specifically a smaller promontory, owned by the John Muir Trust, Strathaird. Beyond the Cuillin and the Red Hills the highest peaks are close to Kyleakin, overlooking the mainland, while the most impressive form the long ridge of Trotternish.

Elsewhere, abundant walking opportunity exists in all the main headlands and around the magnificent coastline; indeed the walk around the Duirinish coastline has few equals in Britain. It is part of Skye’s appeal that each of these districts provides walking markedly different from its neighbours, which in sum, and in its own way, is every bit as satisfying as the Cuillin, Red or Black.

Walkers who combine the pleasure of physical exercise with an interest in flora and fauna, or in the history, culture and folklore of island communities, will simply be spoiled for choice; there is nowhere on the Island that does not reward one’s attention. As the poet Sorley MacLean wrote: ‘a jewel-like island, love of my people, delight of their eyes’.

History

The history of Skye is quite simply a fascinating and time-consuming interest, and is nowhere better explained than in the immense and awe-inspiring detail of Alexander Nicolson’s History of Skye. That is the work to consult: what follows here is, by comparison, a mere crumb from the table of this absorbing topic.

Wherever you go on Skye you will encounter structural relics, ruins of houses, forts, tombs, and so on. The Island is almost littered with chambered cairns, hillforts, duns, brochs, hut circles, souterrains and Pictish stones, all, virtually without exception, dotted along the Island’s tortured coastline. These are all that remain to tell us about the history of man on Skye before the days of the written word, and many of them date back more than 6000 years.

Standing stone, Boreraig village (Walk 2.5)

Imagine, if you will, the scene during the last Ice Age, when Skye lay buried beneath enormous sheets of ice that even then were shaping the landforms with which we later became familiar. As climatic conditions warmed, so the glaciers retreated – a gradual, grinding process that ended between 10,000 and 11,000 years ago. As the incredible weight of ice disappeared, so the land began to rise, and improve as tundral conditions gave way to woodland and mixed vegetation. These conditions suited early stone age (Mesolithic) man, who moved northwards and settled around the new coasts and among the islands. The presence of Mesolithic Man on Skye has not yet been proven; the earliest evidence is from later stone age (Neolithic) times, although carbon dating of finds on the nearby island of Rum to 8000 years ago, the earliest such evidence in Scotland, suggests the possibility that Mesolithic Man did find his way to Skye, and that the evidence of his presence is yet to be found, or has already been lost.

Unlike Mesolithic Man, who lived by hunting and gathering, and moved on in search of food, Neolithic Man preferred a more static existence, staying for longer periods in the same place. This accounts for the far greater number of Neolithic artefacts found not only among the Inner Hebrides, but generally throughout Britain. Neolithic Man moved to Britain from Europe about 6000 years ago, and brought stocks of cattle and sheep, sowing grain and living a simple farming existence.

About 2000 years later (c4000 years ago) the Beaker People appeared on the scene, also moving to Britain from Europe, especially from sites along the Rhine. They are so named from their practice of making ornate pottery. There are two particularly fine examples of chambered cairns dating from this period, one at Cnocan nan Gobhar (NG553173), and the other, reached from Glen Brittle, at Rubh’ an Dùnain (Walk 3.18).

By 3000 years ago, the first hillforts started appearing on Skye, signifying a sometime state of conflict between the local inhabitants and intruders. For about 800 years, hillforts dominated the landscape, varying in size, and usually consisting of a wall around an arrangement of internal buildings. Given the ready availability of wood on Skye, it is more than likely that the wall would have had a fence on top. They were all located on high ground, giving good views, and probably served as a focal point to which people living in surrounding homesteads might have retreated in times of danger.

Gradually, however, the size of these fortifications reduced, and they began to be replaced by duns, and later, brochs. Quite why this reduction occurred is not clear, but it is likely that as tribes became smaller, so the need for large enclosures was less. The result was the ‘dun’, a fairly simple structure, quite often little more than a wall set across a promontory, while a ‘broch’ by comparison was a highly sophisticated drystone structure. The best preserved of the brochs on Skye is Dun Beag, off the Struan road to Dunvegan at NG339386, near Bracadale.

Cill Chriosd church, Strath Suardal (Walk 2.5)

The need for these defensive settlements was probably generated by invasions from mainland tribes. When these became preoccupied with the Roman presence further south, the result seems to have been a much more settled period of existence on Skye, and many of the brochs were abandoned, or robbed of their stone for the hut circles and souterrains that were to follow.

Hut circles were simply a ring of boulders with a wooden structure built on top, and formed the basic homestead for farming communities. Souterrains, however, pose more of a puzzle for archaeologists, but probably served as underground defensive structures against the malice of cattle raiders. One of the best on Skye is at Claigan (NG238539), north of Dunvegan.

There is little left on Skye of the so-called ‘Pictish’ era except a few standing stones, some bearing Christianstyle crosses. A good example is at Clach Ard, 8km (5 miles) north-west of Portree, and bears rod symbols, and those for a mirror and a comb.

Later on, the Christian way of life began to take a hold, reinforced by the visit of St Columba in AD585, and other saints shortly after. But this period of calm was ended after a spell of only 200 years with the arrival of Viking invaders and a new way of life.

The Norse occupation of the Island lasted until the Battle of Largs in 1263, when the fleet of King Haakon was defeated by the Scottish king, Alexander III. Not longer afterwards, in 1266, the Western Isles were ceded to Scotland under the Treaty of Perth.

Yet, with a great independence of spirit for which they are renowned, the Islanders still saw themselves as separate from Scotland, led by the Lord of the Isles. Under his guidance there were many rebellions against the crown, especially during the 14th and 15th centuries, a period also noted for numerous feuds between the island clans. Of these the most prominent were the MacLeods and the MacDonalds, and the Island is spattered with sites of their deeds and misdeeds.

The position of Lord of the Isles was finally abolished by James IV in 1493, although this had little restraining impact on the clan chiefs in spite of a show of muscle by James V in 1540. In that year, he brought a large fleet to Skye, visiting the MacLeod and MacDonald strongholds at Dunvegan and Duntulm respectively before anchoring in Portree Bay for the chiefs to come and pay their respects. Peace, of a sort, did then ensue, but only until the king died, and that only two years later. Clan battles continued to be waged throughout the 16th century, and just into the 17th, when the last battle, that in Coire na Creiche, was fought in 1601.

The Act of Union which followed the death of Elizabeth 1 in 1603, under which James VI of Scotland became James I of England, brought a new source of conflict. During the 17th and 18th centuries life among the islands was coloured by attempts to restore the Stuarts to the throne of England and Scotland which only came to a conclusion in the 1745 Rebellion led by Bonnie Prince Charlie (Prince Charles Edward Stuart). After his disastrous defeat at Culloden (1746), the Prince fled by a most roundabout route that took him to the Outer Isles and to Skye itself, before leaving for the Scottish mainland and France in July 1746.

The 1745 Rebellion raised in Parliament the determination to completely erase the culture that had inspired the rebellion, and outlawed weapons, the Gaelic language and the wearing of the kilt. They succeeded in their aims and peace subsequently came to the islands.

But it was not to last. Poor harvests in 1835 and 1836 and a complete failure of the potato crop in 1846 and 1847 impoverished both the local population and their landlords, and led to a widespread clearance of the land so that the small crofts might be combined to form more profitable areas for sheep grazing. Landlords saw crofters as a burden rather than a means of income, and had little compunction in turning to the more viable sheep farming.

Ruined croft, Erisco (Walk 6.1)

Most of these forced evictions took place between 1840 and 1885, when almost 7000 families were moved from their land and sent abroad, many dying en route. Throughout this book, tales of these clearances appear again and again, and a number of walks visit the sites of former villages. It is a very emotive subject, and I doubt that anyone is proud of what happened, not even those who catalogue it as economic necessity. Towards the end of the 19th century people started resisting the evictions and the tyranny that would often accompany them. Of key importance was a battle between crofters and police at Braes, not far from Portree, which led to a Commission of Inquiry and a succession of crofters’ laws, which enshrined a security of tenure and fair rents, the substance of which remains intact today.

Agriculture still remains a major industry on Skye, but its future now lies in tourism, an economy initiated by the early attentions of Thomas Pennant, Johnson and Boswell, and Sir Walter Scott who visited Skye on his tour of the northern lighthouses in 1814. At the same time the first ‘mountaineers’ turned their attentions to the Island, concentrating almost exclusively, but with immense success, on the Cuillin. Once the whereabouts of the single greatest range of mountain peaks in Britain became common knowledge, tourism gained a momentum it has never lost.

Geology

Almost certainly it will have been the geology of Skye that has brought you to the Island. Not necessarily the study of geology, but the consequences of the processes of tectonic creation that fashioned the profile and landscape of Skye.

Man has probably inhabited Skye for at least 4000 years, but that is a brief moment of Skye’s history, a history shaped over unimaginable years with many tools, the workings of which were at times cataclysmically violent, at others well-nigh undetectable.

As with the rest of Britain and Europe, the geological history of Skye dips back to the Pre-Cambrian era of about 2500–3000 million years ago, although millions of years would elapse before Skye became an island. Quite what the landscape was like in those distant times is only guesswork, but on the basis of geological and topographical studies Skye can be divided into three distinct sections.

Heading for the Quiraing (Walk 6.4)

First, the southernmost part of the island, Sleat, is composed of Lewisian Gneiss, Torridonian sedimentary rocks, Moine Schists and Cambro-Ordovician sedimentary rocks. The already complex interrelationships of these basic rock types is further complicated by extensive thrusting and the transportation of large areas of all these rocks. The present landforms are the product of massive glaciation which over most of the island flowed westwards, but along the east coast flowed northwards.

North Skye, including Trotternish, Waternish and Duirinish, consists of a plateau-like topography punctuated by sea lochs, as at Snizort, Dunvegan and Bracadale. Here, Jurassic sedimentary rocks occur, capped by lavas and pyroclastic rocks from the Lower Tertiary period. Because these rocks dip at a shallow angle to the west, they give rise to steep scarp slopes on the east side, and it is quite easy to pick out the different and distinctive lava layers. One spectacular feature of these rocks is the incidence of landslipped material which developed during Quaternary times; the Storr and the Quiraing are by far the best examples.

The most dramatic scenery, however, is formed from Lower Tertiary intrusive rocks, of which gabbro and granite are the most significant. It is from these rocks that the Cuillin are formed, and the distinction between these rocks and the intrusive acid rocks of the Red Hills is most noticeable as you walk through Glen Sligachan.

During the Tertiary period many parts of Skye were subjected to massive volcanic activity, probably the most violent in Britain. To the north-west of Kilchrist you can still see the vent of an ancient volcano; it has a diameter of about 5km (3 miles). When all that ceased, the island enjoyed about 50 million years of relative calm, until the ice came. The Pleistocene period, the Age of Ice, started about two million years ago, and is largely responsible for producing the landscape we see today. Massive ice sheets covered most of Britain, and huge glaciers flowed across the landscape, moving, plucking, breaking, scratching at the rocks below the ice. When finally they left, they had created a fascinating land form, one that was to be further shaped as sea levels fluctuated, forming raised beaches around Skye, and the agents of erosion got to work.

For a simplified study of these events you should read The Geology of Skye, by Paul and Grace Yoxon; for something vastly more in-depth you need An Excursion Guide to the Geology of the Isle of Skye by B R Bell and J W Harris.

Flora and fauna

In many respects the flora and fauna of Skye does not differ significantly from the rest of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, but on a few counts the Island does stand out rather noticeably. Here you will find up to 40 percent of the world’s grey seals, a high density of breeding golden eagles, an increasing number of white-tailed sea eagles, and a more diverse flora and birdlife than any other comparable area in size in Europe.

And, famously, Skye boasts its own ‘wee beastie’. The midge is renowned worldwide, and can reduce the strongest of folk to tears. Sadly, this scourge of visitors from June to late summer has an accomplice, the cleg, a large horse-fly with a nasty bite. Proprietary defences are available in outdoor shops, and most work, up to a point, for a while. Scientists are working on developing midge-free areas, and on producing a repellent cream based on bog myrtle. A sprig of bog myrtle behind the ear is a traditional remedy of dubious success, while a dab or two of oil of lavender (or, dare I say it, Avon’s ‘Skin so Soft’) has been known to keep the midges at bay for a while, and raise an eyebrow or two if you forget to wash it off again before going into a confined public place, like a bar! Thankfully, midges hate wind, cold and heavy rain, and they should not normally cause a problem on coastal walks or among the high mountains; the theory is that they opt for the easier pickings on campsites.

Adder

How to get there

From any direction, the drive to Skye travels through some of Scotland’s most extravagantly beautiful landscapes.

For all public transport timetable enquiries, call Traveline on 0871 200 22 23 (24 hours, seven days a week). A Skye and Lochalsh Travel Guide is available from tourist information centres or direct from the Highland Council at Public Transport Section, TEC Services, Glenurquhart Road, Inverness IV3 5NX; tel: 01463 702660; email: public.transport@highland.gov.uk. The Council also produces a full map showing all public transport routes in the Highlands.

Cars, bicycles and taxis can be hired locally – ask at the tourist information offices.

By car and motorcycle

Access to the Island by road, without having to resort to ferries, became possible in October 1995 with the opening of the toll bridge from Kyle of Lochalsh to Kyleakin. After the bridge opened, hundreds of protesters from Skye and all over Britain faced criminal prosecutions for refusing to pay the toll, which was the highest in Europe. Now the crossing to Skye is toll free.

The distance from Glasgow to Portree is around 220 miles and the journey time four to five hours, and from Inverness around 115 miles and three hours: these are driving times, and make no allowance for stops en route.

Sunset, Portree Bay (Walk 6.15)

For up-to-date driving information in the Highlands, call 0900 3401 363 (Highland Roadline), 0900 3444 900 (The AA Roadline) or 0900 3401 199 (Grampian Roadline). For road-based journey planning, have a look at the AA or RAC Route Planners online.

By bus and coach

Skye and Lochalsh can be reached by coach from Inverness and Fort William, which have good links to other parts of Scotland. Local buses also operate within the area:

Rapsons Coaches Tel: 01463 710555, info@rapsons.co.uk

Scottish Citylink Coaches Ltd Buchanan Bus Station, Killermont Street, Glasgow G2 3NW, Tel: 08705 50 50 50, info@citylink.co.uk, www.citylink.co.uk.

By ferry

There is an element of romance about reaching Skye by ferry. There are two car ferry services from the mainland: Mallaig–Armadale is operated by Caledonian MacBrayne Limited, and Glenelg–Kylerhea is owned by a community company.

Mallaig–Armadale Ferry

The road journey from Fort William to Mallaig is one of the most scenic ways of approaching the Island; it is matched by an equally beautiful rail journey, which, during summer months, can be accomplished on steam trains. The onward route on Skye takes you from Armadale and via Broadford.

Caledonian MacBrayne LtdThe Ferry TerminalGourock PA19 1QPTel: 01475 650100Fax: 01475 637607Booking hotline: 08000 66 5000

Port offices:Armadale Tel: 01471 844248Mallaig Tel: 01687 462403Uig Tel: 01470 542219.

You can book online at www.calmac.co.uk. Crossing time is 30 minutes. Vehicle reservations are strongly advised. The number of sailings varies seasonally, with up to eight crossings daily (six on Sundays).

Glenelg–Kylerhea Ferry

Approached over Mam Ratagan from Glen Shiel, the subsequent journey to the main Skye road climbs through the rugged Kylerhea Glen, a single track road with passing places and a very steep incline. This is not suitable for large vehicles or vehicles with trailers of any kind.

The Ferry is run by The Isle of Skye Ferry Community Interest Company. For further details email info@skyeferry.co.uk or visit the website: www.skyeferry.co.uk. Anyone can apply for membership of the company, which will provide a 5% discount on ferry fares.

Sailings between Easter and the end of October are from 10am–6pm (7pm June–August), seven days a week, with crossings every 20 minutes. Journey time is five minutes, and the ferry – the Glenachulish – can transport six cars, with standing room only for foot passengers.

By rail

For National Rail Enquiries, call 08457 48 49 50 (24 hours, seven days a week). See also www.thetrainline.com.

There is no rail service on Skye; the closest points you can reach are Mallaig via Glasgow (Queen Street) and Fort William (not Sundays), or Kyle of Lochalsh via Inverness. Frequent daily services run from Glasgow and Edinburgh to Fort William for the Mallaig connection, and to Inverness for the service to Kyle of Lochalsh.

An overnight sleeper service operates from London (Euston) to Fort William and Inverness, stopping at a number of intermediate stations. This service is provided by First Scotrail. You can buy your ticket in advance by visiting www.scotrail.co.uk, or calling 08457 55 00 33 between 7am and 10pm.

By air

There is a small airport on the Island, near Broadford, but no scheduled flights. The nearest airport with scheduled services is Inverness (Inverness Airport, Inverness IV2 7JB; Tel: 01667 464000; website: www.hial.co.uk).

Facilities and accommodation

Portree is the main town on the Island, with a full range of shopping facilities; Broadford also has most facilities.

The range of accommodation on Skye is extensive, including simple bunkhouses, camp sites, bed and breakfast, guest houses and highquality hotels. The Tourist Information Offices will help you with finding accommodation, or you can consult the annual Skye Directory, available from tourist offices. The holiday guide The Visitor is available free at tourist offices and elsewhere.

In addition to that given above, detailed contact information and other useful information is listed in Appendix C.

Using this guide

The Isle of Skye ranges from simple, brief outings not far from civilisation, to rugged, hard mountain and moorland walking – as tough as any in Britain – in isolated locations, where help is far away.

Almost all of the routes covered demand a good level of fitness and knowledge of the techniques and requirements necessary to travel safely in wild countryside in very changeable weather conditions, including the ability to use map and compass properly (but note that the magnetic property of the rock in the Cuillin makes the compass unreliable).

Coire Gorm Horseshoe from Strath Suardal (Walk 2.2)

The walks in this book are widely varied in character and will provide something for everyone, embracing high mountains, lonely lochs, coastal cliffs, peninsulas and forests. Many walks visit places that are less well known, where self-sufficiency is as important as it is among the Cuillin.

But every walk is just that, a walk, and does not require rock climbing or scrambling skills beyond the most fundamental. Even so, the ‘walker’ must be fit and experienced enough to accomplish ascents of the more accessible Munros and high peaks on the island, ascents which, although classed as ‘walks’ remain arduous and demanding. The point of division can best be explained as the moment when hands cease to be used simply for balance and security, and become necessary as an aid to progress. On this basis, Inaccessible Pinnacle remains inaccessible, but Sgurr Alasdair, the highest summit of the Cuillin, is included, in spite of the latter’s toilsome scree slope and airy situation.

Where a walk is substantially available to non-scramblers, the route is described up to the difficulties. For example, the ascent of Sgurr nan Gillean is described as far as the topmost hundred feet or so; beyond that point the walker enters the realms of the seasoned scrambler. When a walk is one that only competent scramblers or rock climbers could realistically attempt, no more than a brief description is given in orange text illustrating that the walk is not suitable for walkers.

All parts of the island are visited, and the chosen walks will provide an excuse for many visits to Skye, and allow walkers to evade inclement weather in one part of the island by taking on walks in another.

Each walk description begins with a short introduction, and provides start and finish points, as well as a calculation of the distance and ascent. The walks are grouped largely within the traditional areas of Skye, and, within those areas, in a reasonably logical order – allowance should be made, however, for the author’s idiosyncratic brand of logic!

Peak bagging

This book has not been written to facilitate peak bagging; in any case, some of the Skye peaks cannot be reached by walkers. But, for the record, Skye has 12 Munros and 2 Corbetts. And if you collect Marilyns, then you have 51 to contend with on Skye and the adjacent islands.

Distances

Distances are given in kilometres (and miles), and represent the total distance for the described walk, that is from the starting point to the finishing point. Where a walk continues from a previously-described walk, the distance given is the total additional distance involved. When a walk is to a single summit, the distance assumes a retreat by the outward route.

Total ascent

The figures given for ascent represent the total height gain for the complete walk, including the return journey, where appropriate. They are given in metres (and feet, rounded up or down). Where a walk continues from a previously-described walk, the ascent figure is the total additional height gain involved.

No attempt is made to grade walks, as this is far too subjective, and depends on abilities that vary from person to person. But the combination of distance and total ascent should permit each walker to calculate roughly how long each walk will take using whatever method – Naismith’s or other – you find works for you. On Skye, however, generous allowance must also be made on most walks for the ruggedness of the terrain and the possibility that any streams that need to be crossed may prove awkward, or indeed completely impassable at the most convenient spot, necessitating long detours or even a retreat.

Access

Walkers in Scotland have always taken access – by custom, tradition or right – over most land and water in Scotland. This is now enshrined in the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, which came into effect in February 2005. The Act tells you where rights of access apply, while the Scottish Outdoor Access Code sets out your responsibilities when exercising your rights. These responsibilities can be summarised as follows:

take responsibility for your own actions

respect the interests of other people

care for the environment.

The sea cliffs of Oronsay (Walk 3.24)

Access rights can be exercised over most land and inland water in Scotland by all non-motorised users, including walkers, cyclists, horse riders and canoeists, providing they do so responsibly. Walkers and others must behave in ways which are compatible with land management needs, and land managers also have reciprocal responsibilities to manage their land to facilitate access, taken either by right, custom or tradition. Local authorities and national park authorities have a duty and the powers to uphold access rights. People may be requested not to take access for certain periods of time when, for example, tree-felling is taking place, or for nature conservation reasons. It is responsible to comply with reasonable requests. Access rights also extend to lightweight, informal camping.

Access rights apply in or on:

hills, mountains and moorland

woods and forests

most urban parks, country parks and other managed open spaces

rivers, lochs, canals and reservoirs

riverbanks, loch shores, beaches and the coastline

land in which crops have not been sown

the margins of fields where crops are growing or have been sown and along the ‘tramlines’ or other tracks which cross the cropped area

grassland, including grass being grown for hay or silage (except when it is at such a late stage of growth that it is likely to be damaged)

fields where there are horses, cattle and other farm animals

all core paths agreed by the local authority

all other paths and tracks where these cross land on which access rights can be exercised

grass sports or playing fields, when not in use, and on land or inland water developed or set out for a recreational purpose, unless the exercise of access rights would interfere with the carrying on of that recreational use

golf courses, but only for crossing them and providing that you do not take access across greens or interfere with any games of golf

bridges, tunnels, causeways, launching sites, groynes, weirs, boulder weirs, embankments of canals and similar waterways, fences, walls or anything designed to facilitate access (such as gates or stiles).

Farmyards are not included in the right of access, but you may still take access through farmyards by rights of way, custom or tradition. Farmers are encouraged to sign alternative routes if they do not want people passing through their farmyard. If you are going through a farmyard, proceed with care and respect the privacy of those living on the farm.

Access rights do not apply to houses or other buildings, or to the immediate surrounding areas including garden ground. Access rights apply to the woodland and grassland areas within the ‘policies’ of large estates, but not to the mown lawns near the house.

The above does not purport to represent a complete statement of the law as it applies in Scotland, and is no substitute for a comprehensive understanding of the situation. However, it is an outline indication of the rights of access as they apply in Scotland.

For more information and to download a copy of the Scottish Outdoor Access Code, see www.outdooraccess-scotland.com or www.ramblers.org.uk/scotland.

ABOUT DOGS

Dogs must be kept under proper control, and should not be taken into any field with young animals in it, or into fields of vegetables or fruit unless there is a clear path.

There is concern among sheep farmers on Skye about the presence of dogs. With increasing frequency you encounter notices that ask you to keep your dog on a lead, or under close control. There is always a good reason for doing so, usually because the walk covers ground close by sea cliffs that is grazed by free-roaming sheep, and over which startled sheep might fall. It is advisable, not to mention considerate, to keep your dog on a lead at all times.

Safety

The fundamentals of safety in the hills should be known by everyone heading for Skye intent on walking, but no apology is made for reiterating some basic dos and don’ts.

Always take the basic minimum kit with you: sturdy boots, warm, windproof clothing, waterproofs (including overtrousers), hat or balaclava, gloves or mittens, spare clothing, maps, compass, whistle, survival bag, emergency rations, first aid kit, food and drink for the day, head torch – all carried in a suitable rucksack.

Let someone know where you are going.

Learn to use a map and compass effectively, and don’t venture into hazardous terrain until you can.

Make sure you know how to get a local weather forecast.

Know basic first aid – your knowledge could save a life.

Plan your route according to your ability, and be honest about your ability and expertise.

Never be afraid to turn back.

Be aware of your surroundings – keep an eye on the weather, your companions, and other people.

Take extra care during descent.

Be winter-wise – snow lingers in the Cuillin corries well into summer. If snow lies across or near your intended route, take an ice axe (and know how to use it properly).

Have some idea of emergency procedures. As a minimum you should know how to call out a mountain rescue team (Dial 999), and, from any point in your walk, know the quickest way to a telephone. You should also know something of the causes, treatment and ways of avoiding mountain hypothermia.

Respect the mountain environment – be conservation minded.

Marsco and Glen Sligachan in foul mood (Walk 2.12)

Maps

1:50,000: All the walks in this book can be found on Ordnance Survey Landranger Sheets 23: North Skye; Sheet 32: South Skye; or Sheet 33: Loch Alsh, Glen Shiel and surrounding area.

1:25,000: Of greater use to walkers on Skye are Ordnance Survey Explorer maps, and for the whole of Skye you will need the following sheets 407, 408, 409, 410, 411, 412 and 413 (www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk).

Also at a scale of 1:25,000 are two maps in the Superwalker series produced by HARVEY Maps (www.harveymaps.co.uk), one of The Cuillin, which covers an area from Glen Brittle in the west to Broadford in the east, and the other of Storr and Trotternish, which covers almost the whole of Trotternish. These HARVEY maps are produced on waterproof material.

Paths

Not all the paths mentioned in the text appear on maps. And where they do, there is no guarantee that they still exist on the ground or remain continuous or well-defined.

A number of the walks go close to the top of dangerous cliffs, both coastal and inland. Here the greatest care is required, especially in windy conditions. Do not, for any reason, venture close to cliff tops. Some of the routes rely on sheep tracks, which make useful paths in otherwise trackless areas. Sheep, however, do not appear to suffer from vertigo, and don’t travel about with awkward, laden sacks on their backs. If a track goes towards a cliff, avoid it, and find a safer, more distant, alternative. Burns should be crossed at the most suitable (and safest) point; they can involve lengthy, and higher, detours in spate conditions. Do not allow the frustrations of such a detour to propel you into attempting a lower crossing against your better judgement.

If there are children in your party, keep them under close supervision and control at all times.

Crossing the river at Camasunary (Walk 3.21)

With only a small but growing number of exceptions, paths are not waymarked or signposted. Many of the mountain paths, however, are cairned. In a constantly developing environment like Skye, changes often occur to routes, especially through forests, or on coastal walks (as a result of landslip, for example). Be aware, however, that there is increasing investment in land management on Skye, and this is producing new fences and gates that may affect the route description. The author would welcome notification of any changes, or difficulties encountered, via the publisher.

Glen Brittle Bay (Walk 3.18)

Following publication of this book, readers should periodically consult the Cicerone website (www.cicerone.co.uk) to see whether any amendments have been recorded.

Language

It is one of the continuing delights of Skye that you can still hear people speaking their native tongue, Gaelic (pronounced with a hard ‘a’, not ‘ay’), and schools on the Island are giving bilingual classes in an endeavour to preserve the language.

While the non-Gaelic-speaking visitor will find their first encounters with pronunciation a confusing and tongue-twisting experience, understanding it is not difficult. The glossary of Gaelic words at the end of the book goes some way to helping with the translation. With only a little persistence, or a polite enquiry of a local, you can quickly gain sufficient mastery to render a good attempt at many of the more complex placenames.

To help with this understanding you will find a number of Gaelic dictionaries are available, along with books intended to assist you in coming to terms with this ancient language.