Читать книгу The Isle of Skye - Terry Marsh - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

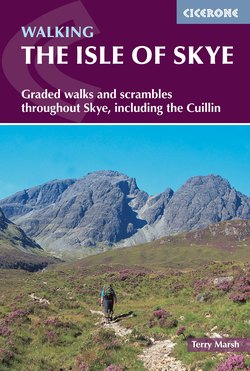

ОглавлениеSECTION 1 SLEAT AND SOUTH-EAST SKYE

Kyle Rhea from the ferry slip (Walks 1.7–1.9)

INTRODUCTION

On the way to the Point of Sleat (Walk 1.2)

Sleat

Sleat (pronounced slate) is the southernmost area of Skye, and projects from the main road between Kyleakin and Broadford near the township of Skulamus. To the north and north-east of this, in that convoluted way Skye has of making a nonsense of contrived partitioning, lies south-east Skye, and the closest point to mainland Scotland. It is here, in a region neither Sleat nor Strath, that you will find the only mountains of note. None is especially distinguished, but all provide excellent escapism from the summer clutter of the Cuillin, with the added bonus of outstanding panoramic views.

The name Sleat, derived from sleibhte, means an extensive tract of moorland, and so it is – a thumb of rugged, rocky, lochan-laden moorland, creased into a thousand folds wherein man has fought with the elements to fashion a living. Sleat is also regarded as ‘The Garden of Skye’ – although not without dissent, as many see the gardens as the product of an time in the Island’s history when clan chieftains succumbed to the rule of London, and rode roughshod over the lives and necessities of their tenants.

The appellation comes, too, from Sleat’s more sheltered environment, protected from the worst of the Skye winds, that allows beech, sycamore and exotic conifers to flourish alongside the more natural birch, alder and bramble. Indeed, as Alastair Alpin MacGregor says: ‘It is at bramble-time that one should visit Russet Sleat of the beautiful women’, a place once governed to a large extent by prosperous tacksmen who personally supervised the cultivation of their own particular farms. MacGregor records: ‘Slait is occupiet for the maist pairt be gentlemen, thairfor it payis but the auld deuteis, that is, of victuall, buttir, cheis, wyne, aill, and aquavite, samekle as thair maister may be able to spend being ane nicht…on ilk merkland.There is twa strenthie castells in Slait, the ane callit Castell Chammes, the uther Dunskeith’.

The history of Sleat is essentially the history of the MacDonalds, in spite of legendary claims that it was the 2nd-century Irish folk hero Cuchullin who came to Dunscaith to learn the art of war from Queen Sqathaich, and the fact that there was a time when all of Skye, including Sleat, was MacLeod territory. By 1498, Dunscaith was in MacDonald possession, and continued to be lived in until the early part of the 17th century. For the walker there is in Sleat none of the rugged grandeur found further north on the Island; indeed much of the interior of Sleat will find greater favour with those more interested in natural and social history than walking. But if the walker comes in search of solitude or peaceful havens in which to reflect for a time, there can be no better place on Skye. Most walks, however, need little description, and little more effort than to park the car and wander about the moorland expanse, or seek out a sheltered nook along the coastline.

The main road, the A851, runs south as far as Armadale, beyond which a minor road makes a valiant, if vain, attempt to probe fully to the Point of Sleat. Many visitors come to Skye, as I did, via the ferry from Mallaig to Armadale, and so gain completely the wrong first impression of Skye. But if you come onto the Island (ideally) from Glenelg to Kylerhea, or Kyleakin via the new bridge, your first taste of Skye will be much more in keeping with the overall ambience of the Island.

With this wider perspective, if you set off into Sleat from Skulamus, you appreciate the contrast fully, especially if you have already toured some of the Island first. You will notice the differences that earned Sleat its ‘garden’ title – differences that give Sleat, in places, an ‘English’ flavour. As Otta Swire comments: ‘Trees abound... every house of any importance has its woods and lawns as in England. Rhododendrons are plentiful and in the spring the bluebells and primroses could vie with Kent. The road is bounded in many places with the type of hedgerow which one associates with Devon lanes, hedges of hawthorn, wild rose, and elder’.

Yet there are also many places where the ‘feel’ is truly that of Skye and the west of Scotland. From Skulamus you first encounter flat moorland and a landscape dotted with island-studded lochans, across which Loch Eishort is sure to catch your eye. It is only as you pass Duisdale, for several generations belonging to the MacKinnons for services as standard bearers to the MacDonalds of Sleat, that a noticeable change occurs. Near magical Isle Ornsay, the road heads away from the coast, and passes by Loch nan Dubhrachan, once inhabited by a monster (The Beast of the Little Horn).

Not far from the loch a minor road loops round to Ord, Dunscaith and Tarskavaig, a splendid drive with many opportunities to patrol the beaches on Sleat’s northern coastline, gazing across Loch Eishort to the mountainous country beyond.

Armadale merely serves to underscore the ‘southern’ feel of Sleat. The castle, built in the 18th century, is attractively set amid woods and lawns. There is some lack of certainty about when Armadale was built. One record claims it for Alexander Wentworth of Sleat, born in 1775; another, published in 1725, mentions a ‘place of residence, adorned with stately edifices, pleasant gardens and other policies called Armodel’; while yet earlier records detail, in 1690, how Armadale House was burned by the King’s fleet.

Sleat does not end at Armadale. Beyond lies Ardvasar, quite a large township on Armadale Bay, and beyond that the scattering of buildings that comprise Aird of Sleat, the final gateway to southernmost Skye at the Point of Sleat.

South-East Skye

With the opening of the bridge between Kyle of Lochalsh and Kyleakin in 1995, the Island, in a sense, lost its isolation, but gained a speedier link between island and mainland, although in reality only the summer months ever saw any significant delay. Quite what the effects will be only time will tell: maybe the tiny ferry that plies between Glenelg and Kylerhea will sink (hopefully not literally) under the weight of purists shunning the bridge in favour of traditional ways of reaching the Island; perhaps someone will devise a bridge to Kylerhea, and blaze a wide road up to the Bealach Udal and down Glen Arroch. (Thankfully, that latter option doesn’t make any kind of economic sense.)

In this first foothold corner of Skye lie the highest summits outwith the Black and Red Cuillin. Just east of Kyleakin, on a small promontory, stands Castle Maol, sometimes referred to as Dun Akin. The main wall was massively damaged in a storm on 1 February 1948. The castle is claimed to have been the residence of a Norwegian princess, known as ‘Saucy Mary’, who may be the princess who lies buried on the summit of Beinn na Caillich.

Typically, this ancient ruin, the very first thing that used to be encountered as you crossed onto the Island, is a classic example of the quagmire you descend into the moment any inquiry is made into the fascinating history of Skye.

Much of Skye’s history is well documented, but the truth about Castle Maol is obscure. According to legend, the castle was built in the 12th century by Mary, who is said to have devised a chain across the kyle from a point below the castle, to prevent foreign vessels from passing until they had paid a toll. One book, however, records: ‘The older part [of the castle] is thought to date back to the 10th century; while the newer portion is possibly early 15th’. It was certainly there in 1513 that a meeting of clan chiefs met to raise Sir Donald MacDonald of Lochalsh to the status of Lord of the Isles. Jim Crumley (The Heart of Skye) claims that Beinn na Cailleach ‘marks the burial chamber of an 8th-century Norse princess who lived at Castle Maol’. Seton Gordon (The Charm of Skye) plays safe, and only ventures to suggest that the princess ‘may have been the same proud ruler who dwelt in Caisteal Maol’. The truth is, it doesn’t matter. No one knows for certain, yet so much intrigue and fascination flows from this one crumbling edifice, and sets a standard by which inquiring minds will clatter away ad infinitum over myriad similar circumstances and queries that Skye has to offer.

A short way round the coastline you reach the Sound of Sleat, and Kylerhea, the place where drovers used to cross thousands of cattle each year to the mainland, at slack water, linked nose to tail, and the first tied to a rowing boat. It must have been a fascinating spectacle, the more so because, as Gavin Maxwell recounts in A Ring of Bright Water, the sound was visited from time to time each year by killer whales.

In the opposite direction you head around the coast to Broadford, through an area, still wooded, but not as densely as previously, that is part of an ancient Caledonian forest.

The hinterland of south-east Skye, between the A851 and the kyles, is wild, rugged and unforgiving, no place for noviciate exploration. With the benefit of experience, however, this rough terrain will provide hours of adventure, and stakes a worthy claim to the attention of all walkers who venture on to Skye.