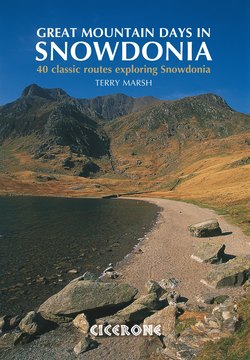

Читать книгу Great Mountain Days in Snowdonia - Terry Marsh - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

On Crib Goch (Walk 1)

In the minds of many visitors, only the mountain ranges that dominate the north-west of Wales are known by the name ‘Snowdonia’ – ‘Eryri’ in the old Welsh. In fact, Snowdonia covers a much wider area, over 2,000km2 (840 square miles), a domain extending far south to Bala, Cadair Idris and beyond, from the northern edge of Cardigan Bay to Anglesey.

Throughout history the mountains of Snowdonia have performed two roles. For hundreds of years, since the Romans sought to colonise the area, they have been a secure and strong defensive barrier, but over the last 200 years they have become an adventure playground. These two opposing views of the mountains might be said to represent those of the Welsh, who live among them, and those of the English, who come to explore. For centuries, the mountains not only provided the local people with pasture for their flocks and the raw building materials for their homesteads, but also hampered the penetration of the pagan attitudes sweeping across England and threatening the flame of Christianity that burned so brightly within Wales.

Today, for better or worse, the mountains of Snowdonia are everyone’s playground. Nevertheless, in these Great Mountain Days you will discover the companionship of solitude, the sound of silence and the tang of wild places, for all are still here, waiting.

About this guide

The 40 walks in this book are grouped into areas defined by valleys, starting from the Snowdon massif, and then rippling away southwards to the Tarrens north of Machynlleth – more a matter of convenience than geographical or geological significance.

Each route description starts with a box containing all the key information about your walk: the distance, height gain, time and grade, and details of suitable parking places. (Some of the parking suggestions are Pay and Display car parks; others are roadside or off-road parking areas where the key thing is to park without causing inconvenience to local people and businesses.) Also provided here are details of places for refreshment after the walk, where they conveniently exist.

Appendix 1 summarises all this route information at a glance.

THE LAND OF EAGLES

Welsh scholars tell us that from time immemorial this untamed, rugged region has been known as Eryri, the land of eagles, ‘eryri’ coming from ‘eryr’, meaning eagle. But it might equally be derived from ‘eira’, making it the land of snow. Some latter-day scholars prefer yet another, rather more prosaic, translation – simply ‘High Land’ or the ‘Land of Mountains‘ – a derivation from the Medieval Welsh for high place. The truth is, no one knows, so you can choose whichever suits you.

I take the view that the lands of Snowdonia are named after eagles, especially as eagles were once here all year round, while snow most certainly wasn’t. These majestic birds have soared above the crags and cwms across the ages, and provided substance for bards, singers and storytellers. Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis), one of the most colourful, extrovert and dynamic of churchmen in the 12th century, writes of

a remarkable eagle which lives in the mountains of Snowdonia. Every fifth feast-day it perches on a particular stone, hoping to satiate its hunger with the bodies of dead men, for on that day it thinks that war will break out.

The stone on which the eagle is said to stand is known as the ‘Stone of Destiny’, thought by some to be Carreg yr Eryr, near Llyn Dinas in Nant Gwynant, and close to Dinas Emrys, the hill fort believed to be the spot that King Gwrtheyrn, better known as Vortigern, chose for his retreat from the unwanted attentions of Anglo-Saxon invaders.

In the 16th century, Thomas Price of Plas Iolyn sends an eagle on an errand to other poets, writing later of the ‘king of mountain fowl’ that dwelt on the ‘clear-cut heights above the rockbound tarn’ in such a way that it is evident that he was writing about something he had actually seen. But by the early 19th century, Snowdonia’s eagles were reduced to a wandering bird, ‘skulking on the precipices’.

Castell y Gwynt (The Castle of the Winds), Glyders (Walk 6)

Pen yr Ole Wen from Cwm Idwal (Walk 6)

Walk grades

The grading of walks anywhere is a very subjective issue; what is ‘easy’ for one walker can be a scary experience for someone less experienced. In reality, nothing in Snowdonia can safely be regarded as easy; the terrain is often bouldery and complex, marshy and trackless, or, more usually, a mix of all of these conditions. But, in order to convey some notion of the effort and walking skill involved in each route, four grades have been employed.

Moderate: the easiest routes, involving walks of any length over any type of terrain; map and compass skills may be necessary.

Energetic: devoid of serious hazard in good conditions, but requiring map-reading and compass skills, generally but not always on clear paths.

Strenuous: involving a fair commitment in terms of time and energy; these may well be rugged walks involving many hours’ walking.

Arduous: covering rough ground, sometimes in remote locations; there may be mild to moderate scrambling. These walks are not necessarily long or time consuming, but they are demanding both of a level of fitness and mountain competency.

Timings

As with grades, timings are also subjective; those given are the times taken by the author (40 years’ experience, and a pensioner, but no slouch – for the present), plus a little extra. It is far better to learn by experience what your own pace is, and then use the distance and height gain information to get an idea of how long it will take you given your personal level of fitness. But be sure to allow for the difficulty of the terrain: for example, the ascent of Tryfan by the North Ridge has a horizontal distance of 1km (just over half a mile), and height gain of 615m (2020ft). This would suggest you could be jumping from Adam to Eve in less than 90 minutes, and indeed some can (I did it myself in 45 minutes, but that was a long, long time ago), but for many walkers, two hours would be nearer the mark because of the nature of the terrain.

Mapping

To aid visualisation, routes are depicted both as line diagrams and as customised HARVEY maps. The former, drawn by author and artist Mark Richards, give an aerial perspective of the walks, while the latter pinpoint the key detail covered in the route description. Harvey maps owe their origins to orienteering, and their bold symbols and distinctive colours make them well suited to outdoor use. Note that key landmarks that feature on the maps and/or diagrams appear in bold in the text to help you plot the route.

Route symbols on Harvey map extracts

Although the guide contains map extracts and diagrams, you are strongly advised always to take with you the relevant sheet map for the route, not only for safety reasons, but also to give a wider picture of the landscapes you are walking through.

At present, HARVEY publish three 1:25,000 Superwalker maps of Snowdonia: Snowdon and the Moelwynion, The Glyderau and the Carneddau and Snowdonia South, covering the Rhinogs, as well as a 1:40,000 British Mountain Map Snowdonia.

Alternatively, the following 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey Explorer maps cover the areas described: OL17 Snowdon/Yr Wyddfa, OL18 Harlech, Porthmadog and Bala and OL23 Cadair Iris and Lyn Tegid.

Welsh place names

The Welsh language (Cymraeg) is an ancient one, emerging in the sixth century from the Brythonic languages, the common ancestor of Welsh, Cumbric, Breton and Cornish. It is a phonetic language, and once the pronunciation of the alphabet has been acquired, a fair stab can be made at the actual words of the language. However, over the years inconsistencies have arisen, most of no great consequence, but sufficient to cause confusion if not explained. Spellings of many Welsh place names have changed over the past 50 years, as use of the proper Welsh language and spelling has gained ground.

For this book, the spelling shown on maps has generally been retained, but not always, especially where it is known to be wrong. (One notable such exception is the spelling of Carnedd Llywelyn. The Lord of Snowdonia was Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, not Llewelyn, as some maps suggest. So Carnedd Llywelyn is used here.) In general correct Welsh has been followed: Cwm y Llan, south of Snowdon, is rendered on maps as Cwm Llan but Cwm y Llan is used in the text. (There is a subtle linguistic difference, but that need not trouble us here.) But this example highlights another issue that crops up throughout the maps of Snowdonia, and varying between OS and Harvey versions. Should it be Cwm y Llan or Cwm-y-llan? Guidance has been taken on these thorny issues from a Welsh-speaker and this accounts for some further variance from the maps for the sake of linguistic accuracy without compromising the clarity of the route descriptions.

Y Garn and Llyn Idwal (Walk 7)

In addition, many names have become Anglicised over the years. In most instances, this book uses what is believed to be the correct Welsh version, departing only rarely in the most widely-accepted cases of Anglicisation, for example the use of Snowdon instead of Yr Wyddfa and Conwy Mountain instead of Mynydd y Dref. Moreover, the author’s local knowledge has led him to name features sometimes not named on the maps at all. Appendix 3 also contains a glossary of Welsh words that you are likely to encounter on your great mountain days in Snowdonia.

Weather to walk?

Mountains everywhere tend to generate their own climate, while remaining subject to whatever is going on nationally. Proximity to the Irish Sea can and does make a difference at times, making conditions change in an instance. So, while out on the hills, you need always to be aware of what is happening to the weather: is the wind changing direction? – are clouds gathering? – is it getting hotter, or colder? Make allowance for the fact that conditions on the tops are generally more severe than in the valleys.

You can get some indication of what might happen by checking the weather forecast both the day before you go and again on the morning you intend to walk. The internet is the best way of checking this, as the websites are regularly updated:

www.metoffice.gov.uk/loutdoor/mountainsafety/snowdonia/snowdonia_latest_pressure.html

www.news.bbc.co.uk/weather

www.mwis.org.uk/sd.php

IN CASE OF EMERGENCY

There are four key mountain rescue services operating in Snowdonia:

Llanberis Mountain Rescue Team (www.llanberismountainrescue.co.uk)

Aberglaslyn Mountain Rescue Team (www.aberglaslyn-mrt.org)

South Snowdonia Search and Rescue Team (www.southsnowdoniamountainrescueteam.co.uk)

Ogwen Valley Mountain Rescue Team (www.ogwen-rescue.org.uk)

The following information is provided by Llanberis Mountain Rescue Team, who, as do other teams, produce excellent information on safety in the hills; theirs is available for download from www.llanberismountainrescue.co.uk. This is what to do if you need a mountain rescue team:

Call 999 or 112 and ask for Mountain Rescue.

Tell them where the ‘incident’ has occurred by giving an accurate grid reference, and the nature of the incident. Give them a contact phone number.

The messengers may be required to wait by the phone for further instructions, and may be used to guide the Team to the exact location of the incident, so they should be the fittest group members if possible.

Be prepared for a long wait – comprised of the time it takes for your messengers to reach a phone, the team callout and assembly time, and the time required for the team to walk to your location with heavy equipment. You may decide that if there is a danger of hypothermia it is best to evacuate most of the party and leave a small group remaining with the casualty. You may also decide that it is necessary to move the casualty to a more sheltered or safer location (if so, ensure that someone will be on hand to guide the Team to your new location).

Consider how group members or passers by can best be deployed, and how the equipment carried by the group can best be redistributed and utilised.

Consider ‘alternative’ uses for the equipment you are carrying, for example camera flashes can be used to attract attention in the dark, a rope laid out along the ground will maximise your chances of being located in poor visibility, and a survival bag can be used for attracting attention.

The standard distress signal is six sharp whistle blasts (or torch flashes) followed by a one minute silence, repeated.

Don’t lose touch with common sense when coming to any decisions!

Pen y Gadair from Cyfrwy (Walk 36)

Before you start

What to wear

Someone once said: ‘There’s no such thing as bad weather, just inadequate clothing.’ Well, as everyone knows, there is such a thing as bad weather, sometimes so bad that no amount of clothing will prove adequate. But the anonymous optimist makes a fair point, and, unless you aspire to being no more than a fair weather walker, then going adequately and suitably clothed facilitates walking regardless of all but the most severe weather conditions. Regular walkers will talk at length (usually in a bar), about days spent in the hills battling wind and rain; it’s a circumstance that breeds its own delightful perversity, a dash of self-esteem at having coped safely with a bad weather day, an exhilaration that is often breathtaking in more ways than one. Let’s face it, if you have to wait for the sun to shine before venturing out, you may never begin.

Being adequately clothed makes all the difference, and well-equipped walkers, enveloped in wind- and waterproof garments, have little to fear from a moderately inclement day.

So, what to wear?

This question can be answered only in general terms for the simple reason that each of us is physically different, we have different metabolisms, our bodies function in different ways when exercising, and the way, and amount, we perspire varies, too. All these factors generate bodily conditions that are specific to each of us and which require individual solutions.

To complicate things even further, there are numerous clothing and equipment manufacturers clamouring to sell you their own brand, but without the certainty that one brand is any more suitable for you than another. It is purely a process of trial and error, often over a period of time, sometimes years. But eventually, you find a combination that works best for you. When you do, stick with it. Just as important, when you settle on the type of clothing that suits you and decide to kit yourself out, go for the best you can afford. Quality really does count when it comes to outdoor clothing.

What to carry

So, what is considered essential? It is not intended that this list should be slavishly followed in every detail by every person in a group, but is suggested as a guide or checklist. Small groups may manage without some items, but if the group is such that it may become fragmented, then it pays to have the key items throughout the group.

Map – everyone should carry a map for the area of the walk, and know how to read it.

Compass – much the same; map and compass are essential.

Whistle – every individual should carry a whistle; it is vital as a means of communication in the event of an emergency. There are numerous, inexpensive mountain and survival whistles available, but any whistle will do.

Torch – you may not intend to be out after dark, but a torch will prove useful if you are. Make sure that every individual carries their own torch, even if there are only two of you. There are many suitable pocket torches on the market, and be sure to carry spare batteries, too. A torch is also useful for signalling in an emergency.

First aid kit – there is nothing worse than a developing blister, or a bad scratch from a bramble. Even the smallest of first aid kits contain plasters or skin compounds like Dr Scholl’s® Moleskin, or Compeed® Blister Packs that can ease the irritation. The kit does not need to be huge, but should include a good cross-section of contemporary first aid products, including ointments and creams suitable for easing insect stings and bites. Today’s outdoor market offers plastic first aid ‘bottle’ kits containing everything you are likely to need for minor emergencies.

Food – it is important to carry day rations sufficient both for the walk you are planning to follow and for emergencies. Every rucksack should contain some emergency foods, like Kendal Mint Cake, chocolate bars or glucose tablets, that remain forever in your pack – although it is a good idea to replenish them at regular intervals.

Drink – liquids are vital, especially in hot conditions, and in winter a stainless steel Thermos of hot drink goes down a treat. Cold liquids can be carried in water bottles or a pliable water container with a plastic suction tube that can be led from your rucksack over your shoulder.

Spare clothing – there is no need to duplicate everything you wear or would normally carry, but some extras kept permanently in your rucksack will prove beneficial – T-shirt, sweater, scarf, spare socks (to double as gloves, if necessary), spare laces

Other bits and pieces – strong string (can double as emergency laces), small towel (for drying post-paddling feet during summer months), notebook, pencil, pocket knife and a thermal blanket or survival bag for emergencies. With luck you will never use it, but half a roll of toilet tissue in a sealable plastic bag can ease many an embarrassing moment.

Cwm Eigiau from Craig yr Ysfa (Walk 15)

RECREATION AND THE MOUNTAIN ENVIRONMENT

[Reproduced with the consent of the Countryside Council for Wales. More information about the need to protect the mountains of Snowdonia, and how that can be achieved, is available from the Council.]

Carnedd Ugain (Crib y Ddysgl) in winter (Walk 1)

Mountains have withstood the rigours of millions of years of geological processes – including mountain building, erosion and glaciation, but, paradoxically, their environments are fragile and very special. Their fragility comes from the harsh climate and landforms which affect the way in which plants and animals can survive there. And they are special because mountains are one of the least human impacted environments. The mountains of Britain support a number of rare species of plants and animals. The effects of ice during the last glacial advance are responsible somewhat for the botanical wealth, producing steep, north facing rocks which provide a suitable habitat for relict arctic–alpine plants which need the cool conditions and freedom from competition from more aggressive grassland species. They also provide a refuge from the attentions of sheep, which manage to graze vegetation in most places in the British uplands, except steep rock faces and fenced enclosures. It is no accident that the best sites to botanise in the uplands are often on rock faces and very steep ground which are effectively mountain ‘islands’, with little surviving woodland or scrub and surrounded by agricultural and urbanised lowlands.

Heather

Tenacious hawthorn

Although the effects of recreation in the uplands may appear insignificant compared to those of other, more substantial and widespread pressures on the countryside, the potential impact is magnified because of the very nature of the sports which we undertake in some of the hitherto least affected areas. These cliffs and summit areas are precisely those last remaining refuges which are so valuable and which conservation organisations are trying to protect. Whether is it ground nesting birds, arctic–alpine flora, blanket bog or the fragile montane heath on the very highest summits, there is a need to be aware of and to protect the special features of the environment we use. There is also the added burden of possible climate change and the results this may have for our upland species.

Generally, most walkers and climbers are sensitive to these concerns and co-operate fully to avoid damage to the special vegetation found in Snowdonia. Examples of damage are rare, but an awareness of the issues is important, particularly as not everyone knows of the special sites or the potential for damage.

Rock lichen

Wild pony, Eastern Carneddau (Walk 12)