Читать книгу Great Mountain Days in Snowdonia - Terry Marsh - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGLYDERAU

On the cantilever, Glyder Fach (Walk 6)

The summit of Glyder Fach (Walk 6)

Black’s Picturesque Guide to North Wales, published in 1857, comments that ‘in savage grandeur the Glyder is not surpassed by any scene in Wales’. A radical observation, but still quite valid. There is something about the Glyders, Glyderau in Welsh, that sets them apart from other mountain groups; there is certainly more visible rock here, strewn randomly in awesome heaps, and lying at jaunty angles, as if someone has tidied up all the loose shavings from mountains created elsewhere, and made them into one great pile until they could figure out what to do with them. This is true mountain ground, rugged and rocky arguably like no other in Britain outside the Isle of Skye, a place where the elemental force of nature is all but tangible.

Anyone travelling from Bangor down the A5 through Nant Ffrancon cannot fail to be awed by the high cwms and soaring rocks walls of the north Glyder ridge stretching from Carnedd y Filiast to Y Garn, by the disturbing atmosphere of the Devil’s Kitchen and its singular gash of Twll Du, the Black Hole, or by the abruptness of the massive wall of Glyder Fach, which serves as a dominating bookend to the long valley. And then suddenly, as the road turns the corner, leaving Nant Ffrancon for Ogwen, the great cliffs of Tryfan hove into view; it is a breathtaking moment that has inspired hearts and tested resolve many times and with equal aplomb.

Tryfan moves you; it is the perfect mountain shape, the stuff of dreams, a sight you will never forget; a paradox, always the same, always different, taking on the light of the moment and playing tricks with it so that it becomes something quite magical. Arrive here from Capel Curig and the form of the mountain rises from the road in magisterial fashion, throwing down a challenge to everyone, a place where the careless, those who do not show it the respect it deserves, can so easily come to grief.

The name ‘Glyder’ has baffled people for many years as to its meaning, but the generally accepted translation is that it means a ‘pile’, or ‘heap’, after the array of tumbled boulders on the summits.

The mountains, rising at their highest to almost 1000 metres, seem to be bound on all sides by steep cliffs, and although this impression eases in the south, along Nantgwryd, better known perhaps as the Dyffryn valley, the severity resumes on the descent of the Llanberis Pass, along which there is a formidable array of cliffs.

Debris, if you can call it that, lies by the road – the Cromlech Boulders, believed to have fallen from the clean-cut angular crags of Dinas Cromlech above. Beneath the boulders, it is said, used to live a gruesome, child-devouring hag, Canthrig Bwt. For many years she was well known among the surrounding farms, and not thought to have brought harm to any children, until a dog was seen to be eating a child’s hand, from which a finger was identified as belonging to a boy who had recently gone missing. The hag was lured from her cave, and beheaded.

Along the southern edge of the range lies the isolated Dyffryn Mymbyr farm sometime home of Esmé Firbank-Kirby. In 1935, she was running riding stables when she met and soon married Thomas Firbank, who had just purchased the 2500-acre mountain farm of Dyffryn Mymbyr. Esmé instantly threw herself into the role of farmer’s wife, and shared her husband’s zeal for the powerful landscapes of Snowdonia. Those early years at Dyffryn were later immortalised by Thomas in his best-selling novel I Bought a Mountain. After the outbreak of the Second World War, Thomas, like so many young men, went to fight, and although he survived the war and earned great distinction, he never returned to the farm. Life then was desperately hard for Esmé, but soon after the war she met and married Major Peter Kirby. From then on, Esmé was an ardent conservationist, becoming the founder of the Snowdonia National Park Society, and, later, the Esmé Kirby Snowdonia Trust. She died in 1999, at Dyffryn Mymbyr, and her remains lie buried on her beloved mountain.

Sadly, the northern end of this compact range has been despoiled, mainly by the extraction of slate both at Llanberis and near Bethesda. More recently, but less intrusively, the mountains have been used for a hydroelectric scheme involving the low-lying Llyn Peris and a high glacial lake, Marchlyn Mawr, which fluctuate in their daily process of providing power.

The mountain massif is crossed by one long route, the Miners’ Track. It starts from behind Pen y Gwryd and slants up to a boggy plateau near Llyn Caseg-fraith. The route then slips in a north-westerly direction across the head of Cwm Tryfan to cross Bwlch Tryfan and skitter downwards, past Llyn Bochlwyd to Ogwen. The route is the product of the days when hardy miners crossed the mountains every week between their homes in Bethesda to the ill-fated mines of Snowdon.

The Glyders are not a huge group, in reality just one long ridge, kinked in the middle, and with bits stuck on the sides. You could walk from Capel Curig to Bethesda or Llanberis along the ridge in a full day, but in this instance the individual parts offer better walking than the whole, not least because then you have left yourself something for another day.

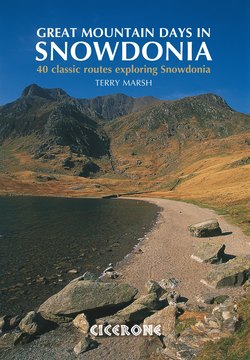

Llyn Bochlwyd with Y Garn and Foel Goch in the background (Walk 6)