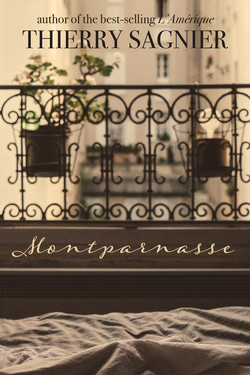

Читать книгу Montparnasse - Thierry Sagnier - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 7

James Johnson stared at the sketch; the sketch stared back. He stood, moved both the easel and canvas closer to a window.

The eyes were wrong. They failed to convey the young man’s cavalier good looks, his daring and courage. Instead, the face showed a certain cruelty, a hint of rudeness in the lips and cast of the mouth. James tore a blank sheet of newsprint from a pad and, with a stick of charcoal, drew a new chin, softer lips, a thinner, more muscular throat.

From the apartment’s open front door came a brief knock, a throat clearing. “C’est votre frère? Your brother, yes?”

Johnson turned, nodded and smiled.

Monsieur Hippolyte Lefebvre came twice daily, at 10 a.m. and 3 p.m., and though he rarely had correspondence of importance or interest, Johnson always welcomed the man’s arrival.

The mailman was almost a foot shorter than Johnson but stood erect as a stake. For the first few months, M. Lefebvre had not been communicative, regarding the American artist more as a peculiarity of time and place than as a human. Johnson was a Ricain, a madman who had chosen wartime France over Philadelphia for unclear reasons that reflected what the mailman called “la folie américaine.”

Over time the two had become friends, or, at least, close acquaintances. M. Lefebvre’s, “Bonjour, Monsieur Johnson!” brightened the expatriate’s day. The little facteur made the effort to pronounce Johnson’s name as well as he could, though he failed to understand why there was an h between the o and the n. Plying him with an ocean of café-crème, Johnson had learned amazing things.

M. Lefebvre knew, for example, that the younger sister of Mademoiselle Gauthier, across the hall and down, was not a sister at all but a daughter, the issue of Mlle. Gauthier’s brief encounter with an American Army captain in 1904. This, Johnson decided, accounted for Mlle. Gauthier’s mother/sister aloofness when he accidentally met them in the hallway. The daughter/sister kept her eyes averted, but once flashed an irreverent grin when her mother/sister was not looking.

M. Lefebvre also knew that Monsieur Dupont, the dour baker at the nearby boulangerie, was conducting an affair of the heart with Madame Ribaud, owner of the flower shop across the street. Mme. Ribaud was far older than the 30-ish M. Dupont, a round, triple-chinned man, the product of his doughy environment. She, in turn, looked much like the pressed and faded flowers in her window display.

Then there was the Delâtre family, who had a boy, 6 years old now, with a head as large as a medicine ball, supported by complex braces attached to his waist and back. M. Lefebvre was friends with the Delâtre’s maid, a country girl from Auvergne, who told him the boy was kept in a small room beneath the servants’ stairway and fed only mashed potatoes and boudin sausage.

Of course, Mesdemoiselles Clothilde and Henriette, who lived in the apartment directly above Johnson’s, were not sisters at all, but followers of Lesbos. With a disapproving look, Mr. Lefevbre told of the magazines the women received, publications singing the praises of same-sex love.

M. Lefebvre knew all this and more. The facteur had a Parisian way of erasing any doubt concerning his veracity: a raised eyebrow, a slightly curled upper lip, a deprecating hand gesture which might be effeminate anywhere else, but in Paris obviated the need for explanations.

The mailman was learning English from a thin, brown-cover book he kept in his satchel. He was proud of his growing vocabulary and had asked Johnson to write down one new word a day, which he repeated as he walked his mail route.

Yesterday the word was “chip.” There had followed a bilingually complex conversation, and the mailman twice threw up his hands in despair and disgust as Johnson enunciated the differences between chip, ship, cheap, sheep, and cheep. To the postman’s French ear, the five words sounded exactly the same. So did bore, boor and boar. Big, bag, beg, bog and bug tortured him. His lips generated grimaces that did nothing for his pronunciation. He found English grotesque yet fascinating.

Pepper, paper, peeper and piper. The more confusing the word, the longer M. Lefebvre lingered over his coffee. Johnson had thought to enter the dark domain of George Bernard Shaw’s ghoti, where gh may be an ef, an o sounds like an ee, and ti becomes sh, so that ghoti is pronounced fish, but he decided the mailman might think this an American’s revenge on the anarchistic French language, with its incomprehensible tenses, silent x’s, silent h’s, and barbarous use of vowels.

Hippolyte Lefebvre had the soul of an adventurer. He had read everything he could find in French written by Jack London, and though he did not approve of the author’s scandalous divorce, he still wished he could emulate him. There were distant relatives in New York he had dreamed of joining after the war. He yearned to be a cowboy, or a taxi driver in Hollywood where customers paid in hundred-dollar bills and everyone owned a new Ford. M. Lefebvre, unmarried and occasionally despondent about his bachelor status, also thought of becoming a polygamist Mormon. Johnson thought it unwise to ask how the mailman planned to acquire several wives in Utah, when he had been so unsuccessful in getting a single one in postwar Paris, where the dearth of younger men made for astonishingly aggressive women.

Johnson did his best to keep the man’s reveries within bounds by citing known American dangers: wild Indians with a penchant for scalps and influenza, murderous Mexicans, Irish and Italian thugs, and buffalo stampedes. Still, Johnson knew, Lefebvre would be an exemplary immigrant, and he sometimes felt a twinge of guilt over his own lack of patriotic encouragement.

From his ground-floor apartment next to the concierge, James Johnson could spy on the lives of his neighbors.

Not a day went by that he did not see a grand mutilé, one of the countless, brutally wounded war veterans—France’s bitter war harvest. He shuddered every time, remembering the mud, the ambulance, the blood.

The disfigured were treated with great respect. Strangers opened doors, helped them cross the streets, viewed them with deference as the heroes they were. They received preferential treatment in shops, theaters and housing, and many still wore their medal-bedecked uniforms. Some were accompanied by attractive young women who, Johnson suspected, were not above calculating to the very last centime what the assistance familiale and retraite militaire might bring.

These maimed survivors were mostly farm boys from the Vosge, Bretagne, Camargue and Flandres.

Many were blind; those who still saw had weary, hooded eyes. They sat at the cafés, empty sleeves and pant legs neatly pinned, gazes fixed on something far distant. Many drank too much, and there were newspaper reports of their paltry crimes—petty thievery, nonpayment of bills after gargantuan meals in expensive restaurants. The authorities were lenient. Yesterday’s France-Soir newspaper reported a fight among a group of grands mutilés during one of their battalion’s monthly reunions held in Montmartre. It took almost 20 police officers to quell the riot. Mme. Bertrand, the concierge in Johnson’s building, had told him in hushed tones that though she had the deepest respect for the gueules cassées—the broken mouths—she didn’t want them in her building. They were known to complain incessantly.

After M. Lefebvre’s morning visit, James Johnson planned to take his easel, palette, brushes and paints to the Opéra. He had found an interesting view of the grand old building, where shadows played across the statues of the Muses, bringing them to life. In the evening, there would be a meal and a walk to the Rotonde to watch the others discuss and argue their work. His French was improving, and once or twice he’d participated in discussions, but mostly he watched and he listened. The others called him Le Grand Muet, the tall silent one, and some, he knew, thought him a snob.

With luck, he’d see Kiki tonight. She often came to the Rotonde with a gaggle of loud girlfriends who dressed outrageously. Funny hats were the fashion; last week Kiki had worn an amazing assemblage of feathers, random pieces of silk and gossamer, all taped or pinned to a cloche perched precariously on her head.

M. Lefebvre did not like artists, or their entourage. He called them sang-sus, leeches, and opposed the government’s modest sponsorship of the arts. He believed all painters, poets, playwrights, novelists, writers, sculptors, musicians, actors, dancers, and singers should be forced to bathe and get jobs, preferably menial ones. Johnson knew he was spared this contempt only because he was an American with means of his own. He was fortunate; Americans were popular. They had the reputation of being deferential and polite, were considered slow to anger and were expected to tip well. They had no need to explain their foibles to anyone, including M. Lefebvre.

The mailman, who had come an hour earlier for his English lesson, put down his coffee cup and smacked his lips. “Excellent, Monsieur Johnson! Like always, yes?”

Johnson corrected him, “As always, Monsieur Lefevbre. As.”

The mailman made a face, shouldered his big leather bag, “As always. As always.”

He left with a smile and a wave, and Johnson glanced at the correspondence, which consisted of bills, a letter from his father in the States, and an envelope from La Défense; undoubtedly something about Daniel, his missing brother. He opened it. It had been several weeks since the last note from La Défense on its efforts to determine his brother’s whereabouts, or those of his remains. Johnson knew that if the French government’s attempts seemed halfhearted at best, there was at stake the reputation of the Lafayette Escadrille, with which Daniel had worked as a mechanic before he’d fancied himself a pilot and stolen a plane, presumably to prove that he could fly.

Their father, James Johnson Senior, could not accept that Daniel might be dead, and had for more than a year been engaged in a correspondence with Edgar Cayce, the spiritualist, who had persuaded him that Daniel had flown the airplane to Greece and was alive and well on one of the smaller islands—never mind that the Nieuport 11 could not carry enough fuel to attempt such a trip. Johnson Senior had asked his surviving son to contact the Greek Consul and secure that government’s help.

Three of the Escadrille flyers with whom Johnson had corresponded believed Daniel had crashed his plane somewhere in the Massif Central. None of them seemed to bear him a grudge. Rather, they were bemused and somewhat impressed with his bravado. “It’s not every day,” said one flyer, “that a mechanic steals an airplane.”

In the street, two children were kicking a red rubber ball. Johnson closed his eyes, recalled early memories—Daniel sitting on his chest, suffocating him with his weight, hitting him with a rock dead in the center of the forehead, where he still bore a faint scar, telling lies to their father, lies that were always believed. Plumbing the depths of his personal history, Johnson could not find a single example of Daniel’s actions ever benefiting him.

I hope Daniel is alive, Johnson thought; I truly do, and I would be delighted to have him appear at my front door. I also hope I never see him again. I came to France partly to get away from my evil sibling.

God has a sense of humor.