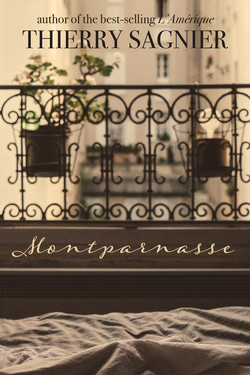

Читать книгу Montparnasse - Thierry Sagnier - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 13

The first woman was Jeanne-Marie Cuchet, a 39-year-old widow whose late husband had been killed in battle early in the war. She and her son, André, 17, died in Landru’s rented villa in Vernouillet one night in May 1915.

The three had spent the night there, he and Jeanne-Marie in the upstairs bedroom, the son in the guest room on the second floor. She had been passionate, Landru less so. He did not really find the woman attractive—her nose was too large, her hips were rubbery, her pubic hair was beginning to gray—and he was annoyed by her voice, high-pitched and grating. Still, she had 17,000 francs in a savings account, and several pieces of acceptable furniture in her apartment. In bed that night they played a game where he bound a scarf over her mouth, supposedly to muffle her moans and protect her son’s sensitivities. In fact, Landru had discovered, Jeanne-Marie liked to talk during the act, and he found this habit disagreeable and unnecessary.

The next morning he prepared a petit déjeuner of café au lait et tartines. He knew André and his mother each laced their coffee with 4 teaspoons of sugar—a habit that he, as a former soldier, found sinfully wasteful—and so to the sugar in the bowl he added a powdered cyanide-based rat poison bought at the local hardware store. The Cuchets, mère et fils, drank their coffee in one swallow. He turned his back to them and busied himself at the stove fixing more grilled bread. Within minutes, André dropped his bread and orange marmalade on the floor and convulsed. He fell off his chair, lay on his back and his breathing became labored. Jeanne-Marie screamed and Landru rushed to the boy’s side just in time to see her fall as well. Landru rose, poured himself a cup of coffee, and watched as both died. By his watch, it took 12 minutes for André and nine for Jeanne-Marie. André had vomited, which Landru found reprehensible, and when he went to pick up Jeanne-Marie, he noticed her bowels had failed.

He grabbed the woman’s body under the armpits and dragged her through the kitchen door to the walled backyard. He stripped off her clothes and, with a ladle, bath brush and a bucket of cold water, cleaned her. He repeated the process with her son. Then he knelt and carefully listened for heartbeats. There were none.

He checked his watch. The train for Paris would be leaving in an hour. Not enough time for dismemberment. He dragged the bodies to the garden shed, found a large, paint-splattered drop cloth, and wrapped it around the victims. He tucked the two bodies in a corner of the shed behind some gardening tools. Disposal would come later.

The day before, he had bought four train tickets to Vernouillet; three one-ways and one return. That had saved him seven francs. He found his ticket on the bedroom dresser, looked once around the house. He left the cups on the table, but made sure to put away the sugar bowl. He disliked ants. He left the house, carefully locked the front door, and walked to the train station.

He spent that night at home with his wife, Marie-Catherine, and three of his four children: Maurice, Suzanne and Charles. Marie, his oldest, was already married and living with her two children in Montpelier.

He entertained them by humming a recent Debussy composition, affecting different tonalities for the various instruments. Marie-Catherine laughed and clapped, but Maurice, his oldest son, was in a dark mood. Earlier, his father had said that in the morning Maurice was to help him transport the furniture of a Mme. Cuchet and her son to a holding garage. Five rooms would have to be moved, and the work would take all day.

Thérèse Laborde-Line died in June 1915. Born in Argentina and separated from a hotelier husband who abused her, she too had answered one of Landru’s ads, had been wooed, taken to Vernouillet and poisoned. She was a medium-sized woman with large bones, small breasts and strong hips, and most men would have called her plain. Full, pouty lips rescued her face from complete anonymity. She knew this and, free of her husband, had parlayed her marginal looks into three bad dalliances, one on the heels of the other. Landru—though she knew him as Marcel Veron—promised to change her life and carry her away.

Earlier that week, Landru had returned to Vernouillet and buried the remains of Jeanne-Marie and André Cuchet in a far corner of the local cemetery. The war produced graves daily; mounds of fresh earth in the graveyard were not suspect.

He had promised Thérèse Laborde-Line a lovers’ weekend in his villa, but was silently repulsed by her lack of hygiene. She smelled poorly, and the skin on her neck was gray from lack of soap and water. He did not engage in sex with her, blaming an unexpected bout of colitis. Thérèse bore her disappointment well.

After feeding her a salad and some cold chicken, Landru this time chose strychnine, mixing a generous teaspoon of the chemical in Therese’s evening cocoa. She made a slight face as she drank and complained briefly of the chocolate’s bitterness, but he assured her it was a special mix from Abyssinia, and as she emptied the cup, Thérèse once again thanked the heavens for sending her such a devoted man. Imagine that! Chocolate from Abyssinia! For her!

He was amazed at the effect of the strychnine. Thérèse’s neck seized, the cords and muscles etched in sharp relief to the gray skin. Her face froze into a toothy rictus, eyes wide open, frothed mouth in a distended O. Landru, watching, wondered if the odiferous woman knew what was happening to her. He doubted it.

Her arms flapped as if she were trying to fly, then her legs buckled. She jackknifed at the waist, repeatedly slamming the back of her head into the floor, moaning loudly, and Landru, concerned by the noise, squatted on her chest to hold her down. Her convulsions threw him off. She made a gurgling sound in her throat, arched her back until only her heels and head touched the bedroom rug. She collapsed and rose again once, twice. Her forehead running with sweat, she stared at her murderer with wondering eyes, seeing nothing. Her face turned a pale blue, and she bit her lower lip. The blood flowed down her chin and onto her blouse. In less than eight minutes, she was lifeless.

Landru sat in the leather easy chair that had belonged to Jeanne-Marie Cuchet, took out his pen, glanced at his watch and wrote the hour and minute carefully in the little notebook he always carried. The late Thérèse surprised him by farting once, very long and very loud like a balloon losing its air, and Landru waved the stink from his face. He frowned at the body, said, “Vraiment, Thérèse, ce n’est pas très élégant, ça.”

Later, he dismembered her with a butcher’s saw. He wore a thick canvas apron that covered him from neck to ankle, and he worked methodically and without talent, cutting through muscle and bone and feeding the pieces of her into a large stove. He had overseen the stove’s installation himself, ensuring a good strong draught in the flue, which rose straight through the roof and out the chimney.

Her remains were gone just before sunup, and by the time he cleaned his tools, scrubbed the floor, sink and apron with bleach and water, the morning was full on. He stirred the ashes with a long metal pole and was pleased to see nothing large remained unconsumed by the fire. He was exhausted and slept until late afternoon, then took a cab to the station and returned to Paris on the 7 o’clock train.