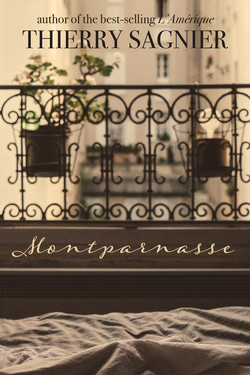

Читать книгу Montparnasse - Thierry Sagnier - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

There were times when Landru opened his eyes early in the morning having forgotten who he was. He didn’t like the feeling; it implied a weakness easily exploited, so he would lie in the bed and rediscover himself by staring at the woman sleeping close by. Was it his wife of 18 years? His most recent lover? The latest war widow from the personal advertisement in Le Matin? It was easier if there was no woman, no middle-aged Dômestic with folds of pale skin beneath her chin and a government pension. Then he could choose who he was that day.

He had worn so many names. His life had been a series of small crimes marred by unforeseen evidence and followed by arrest, prosecution and sentence, parole and release. Then, a new name and a new identity. He was a failed criminal, what the gendarmes called a petit forban, rarely showing a profit from his schemes. If there was money, it sifted through his fingers, apportioned to his wife and four children, to his mistress of the moment, to planning the next doubtful adventure. He considered himself an exemplary father and a doting husband. His own father, an honest provider, had been so ashamed of his son’s endless skirmishes with the law that one somber day in October 1913 he had hanged himself in the Bois de Boulogne.

Henri Désiré Landru (the “Désiré” reflected his mother’s desperate desire to have a boy) hardly noticed his father’s suicide. He did not attend the funeral; he did not send flowers or a card expressing his sympathy. He did not tell his children that their grandfather had passed away. He did, though, find and keep the man’s identity papers, birth certificate, and bank book, since these might come in handy. Landru’s years in jail had been spent with petty thieves, pimps, addicts and suppliers, strong-arm men, bigamists, deserters and other truants. He knew the value of a dead man’s personals.

He was dapper if not elegant, with piercing eyes. One woman had called him “parfaitement proportionné sauf pour ta tête,” and it was true. His arms, legs, feet, torso, were the stuff of a sculptor’s model, but his head was overlarge on a thin neck punctuated by a lump of an Adam’s apple. His mustache and beard were perfectly trimmed, his fingernails clean and well cut. He had smooth, taut skin stretched over perfect bones. He neither drank nor smoked, though he had a fondness for dark chocolate from the colonies. At the height of his infamy, he had seen himself declared in print as a student of Franz Mesmer.

In reality, he had been an undecorated soldier, a bicycle mechanic, a brilliant but tragically unappreciated inventor. Still, he was well-spoken, smelled of cologne and ironing starch. If he wished to amuse, he could contort his body like an acrobat and juggle plates and glasses. He could sing the aria of the day’s operetta. He had discovered in himself a charm that, nurtured and played properly, provided a steady stream of goods he could sell, and bank accounts he would pilfer.

His attitude toward earning a living had changed over the years. At first, he had abhorred the idea of a steady job, and had searched for easier, quicker roads to profit. He had hoped to be an entrepreneur, manufacturing motorcycles, but had little success. There had been other businesses, other initiatives, endeavors that had worked for a while, then failed. Mostly there had been widows.

In 1915, France was creating 12,000 widows a day and Landru was corresponding with more than 250 of them. They were young, old, seldom well-educated, though he insisted they be able to read and write. When they responded to the small advertisements placed in the personal section of Paris newspapers, they were hopeful, delighted by what he claimed to offer, easily wooed and trusting beyond the norm. They knew him as Monsieur Petit, Monsieur Legrand (a small joke he allowed himself), Monsieur Freymier, Monsieur Dupont. He was an international engineer, the owner of a rubber plantation in Brazil, a secret government agent soon to be sent overseas to promote the war effort, or the next consul to Australia. He wrote charming letters, sent flowers and candy, squired them about town. They found his habit of noting every expense in a small cahier charming and responsible. In bed with him, they discovered passions never before explored, and when over a lunch of pâté et fromage he held their hands in his, stared deeply into their eyes and proposed, they accepted immediately and with gratitude. Soon, he would suggest they move in together, since they would shortly be going abroad for his next posting. He would volunteer to sell their furniture, and arrange for the banks to open new accounts that could be accessed from wherever they might be assigned.

He was a man of mystery, of taste and refinement. The widows gloried in his company.