Читать книгу A Fortune-Teller Told Me: Earthbound Travels in the Far East - Tiziano Terzani - Страница 10

CHAPTER SIX Widows and Broken Pots

ОглавлениеIt was inevitable: I began to have doubts. Along came the old familiar voice of my alter ego, true to form, ready to question every certainty. The doubts first surfaced when I began investigating the topic of fortune-tellers and superstition from the point of view of a journalist. Was I not perhaps wasting my time with this business of not flying? Had I not succumbed to the most foolish and irrational of instincts? Was I not behaving like a credulous old woman? As soon as I looked at the subject with the logic I would have applied to anything else, it struck me as absurd.

I began by going to interview General Payroot, the secretary of the International Thai Association of Astrology. He was a distinguished looking gentleman of about sixty, lean and erect, with thick grey hair, cut very short like that of a monk. When I came in he handed me not one but, as happens more and more often in Asia, several visiting cards, each of which gave a different address and different telephone and fax numbers.

‘Why the International Thai Association of Astrology?’ I asked, to start the ball rolling.

‘We also hold courses in English, for foreign students; last year we had two Australians.’

It doesn’t take much to become international, I thought; and I imagined those two, now in some Australian town, making a living by saying heaven knows what about people’s destiny, with the prestige of having studied in Thailand, one of the great centres of the occult.

‘Also,’ continued General Payroot, ‘we maintain contacts with the astrological associations of various countries. The German one in particular.’

‘The German one?’

‘The Germans are at the cutting edge in this field; they are brilliant. I myself have studied in Hamburg.’ He had indeed: years ago this distinguished gentleman – in all truth an infantry general in the Royal Thai Armed Forces – had been a cadet at the famous Führungsakademie. In the morning he had attended classes in warfare, and in the evening he had learned about the stars at the local Institute of Astrology.

After retiring from the army he devoted himself full-time to his two pet creations: a school for fortune-tellers, with the specific intention of disseminating the ‘German method’, and an ‘astro-business’ company which combines astrology with economic research to predict the behaviour of the stock market. ‘The system is already fully computerized,’ the general explained to me proudly. Clients paid an enrolment fee plus 5 per cent of all profits from investments recommended by the ‘astro-business’.

My meeting with the general-astrologer took place in the headquarters of the Academy of Siamese Astrologers, a handsome, spacious wooden villa built at the beginning of the century. The floors were of polished teak, the open verandas were ventilated by large fans revolving slowly on the ceilings. The setting had much to recommend it, too, being at the centre of one of those neighbourhoods that have best preserved the atmosphere of old Bangkok. Across from the Academy is the Great Temple, which in Thailand is rather like the Vatican, being the residence of the Patriarch, the head of the Buddhist Church.

I had arrived early in the morning. Along the pavements were dozens of stalls displaying religious trinkets. There were lucky charms and amulets against the evil eye, statuettes of divinities and venerable abbots from ages past, and the highly realistic little wooden phalluses which it is believed increase male virility and make women give birth to boys.

The Thais have unbounded faith in the powers of the occult, and these little markets of hope and exorcism are among the most colourful and profitable in the country. No Thai walks out of the door without carrying some amulet or other. Many wear whole collections of them around their necks, hanging from thick gold chains. Thais will spend huge sums to procure a powerful amulet, or to be tattooed with signs that can ward off danger and attract good luck. No part of the body is spared: it is said that a certain lady who recently became the wife of one of the most prominent men in the country achieved her goal thanks to some very special shells tattooed on her mount of Venus.

While I was talking with the astrologer-general in the main hall of the Association, from two adjoining rooms came the voices of teachers giving lessons to classes drawn from all over Thailand. Even astrology has been affected by the process of democratization. Originally it was a court art, studied and practised only by kings or for kings. Knowledge of the stars and their secrets was an instrument of power, and as such had to remain a monopoly of the few. Now astrology, too, has become a consumer good, accessible to all. Rama the First, the founder of the dynasty that currently reigns over Thailand, was an excellent astrologer, and predicted that 150 years after his death there would be a great revolution in the country. And lo and behold, at the time appointed, the revolution occurred: in 1932 the absolute monarchy was forced by an uprising of intellectuals and progressive nobles to become constitutional.

‘And the present king, Bumiphol, is he a good astrologer?’ I asked.

‘I cannot say anything about my king,’ replied the general, avoiding a subject which is still very much taboo in Thailand. There are too many unresolved mysteries, too many whispered prophecies – including the one about the dynasty coming to an end with the next king, Rama the Tenth – for a Thai to discuss the royal family with a foreigner. The general even refused to admit what everyone knows: that King Bumiphol, like his predecessors, has astrologers in his service, and it is they who determine the times of his public appearances and fix his appointments.

The Academy has a small garden, unkempt but not unpleasing, with a litter of newborn kittens and a couple of mangy dogs, some shirts hung out to dry, and a cement deer pretending to drink from a waterless fountain. Along the verandas stood a number of small tables, each with a palmist studying the lines of a proffered hand with a big magnifying glass, or an astrologer making calculations and drawings on sheets of squared paper and recounting the past, predicting the future, or just giving advice to intently listening women.

Was I becoming like them, even if with the justification of wanting to explore ‘the mystery of Asia’? In accepting the injunction not to fly, was I not perhaps behaving like those little old women who came to receive from the stars some constraint or prohibition in the hope that gain would ensue?

I stopped to watch a woman who had brought not only her daughter but the daughter’s fiancé, obviously to have him vetted before considering him as a potential son-in-law. As the fortune-teller performed his calculations they all looked on with intense absorption.

The general told me that that very day, it so happened, one of the most famous seers in the country had come to the Association, a woman who combined various methods of divination, but who was especially expert in the reading of the body. Was I interested in consulting her?

‘Of course,’ I said instinctively, realizing as I did so how this fortune-telling business could easily become a drug, and how one might spend one’s life listening to essentially the same things, asking the same questions, each time waiting for the answer with fresh curiosity. So it is, too, at the casino when you put a handful of chips on the black or the red, on the even or the odd numbers: the more you play the more you want to, and you never get bored waiting for that ‘yes’ or ‘no’ of fate. And, just as at the casino one who loses is sure his luck will soon change, so it is with fortune-tellers: after hearing so many of them come out with perhaps one true and interesting point amidst a plethora of errors and banalities, we still hope to come upon the most gifted of all, the one who is never wrong, who sees everything clearly. Could it be the next one?

The woman was about fifty, stocky and broad-shouldered, with short legs, her hair still black, and light skin. She was clearly of Chinese origin, but I didn’t mention this – I didn’t want to get into a conversation that might give her clues as to who I was and where I came from. I sat opposite her without saying a word, and waited for her questions.

She sat for a few minutes as if in prayer, whispering some formula with her hands joined in front of her chest, her head slightly bowed and her eyes closed. She then peered into my face with great concentration and asked me to smile, saying she wanted to examine the way my mouth creased; she touched my ears and the bones of my forehead. Finally, she had me stand and lift the cuffs of my trousers, to get a good look at my feet and ankles.

This is an old Chinese system of divination, and it interested me because, of all the various systems, this one seemed the least nebulous. A body, closely observed, can say a great deal, and if there is a ‘book’ in which to read someone’s past – and maybe a hint of his future, too – it must surely be that shell of life that people wear from birth, rather than some manual of calculations based on the relation between the stars and the hour when one came into the world. People born at the same hour of the same day of the same year do not share the same fate, and they most certainly do not die at the same time. Nor do they have the same creases in their hands. But people with similar physical characteristics do often have similar attitudes, similar qualities and defects. So it is not impossible that one may be able to read in a person’s body the signs of his fate.

The reading of people’s destinies in their faces evolved in China from medical practice. Patients, especially women, would not allow anyone to touch them, so the doctors had to diagnose their ailments just by looking at them, especially their faces. By dint of observing vast numbers of patients, century after century, the Chinese have concluded, for example, that a small red spot on a cheek denotes a heart malfunction; a wrinkle under the left eye means a stomach problem. Similarly, all rich people are meant to have a particular curve of the nose, and people with power have a mole on the chin. Hence the idea that destiny is written in the body: one need only know how to observe it.

The Chinese discern the character of a person by his ears; in the forehead they read his fate up to the age of thirty-two, in the eyes up to forty, and in the nose from forty to fifty. The eyebrows show the emotional life, and in the mouth are the signs of good or bad fortune in the last years of life. In the crease of the lips, which changes with time, can be read what a man wished to be and what he has become. Not all that crazy, I thought. The body really can be an excellent indicator. Is it not true that after a certain age one is responsible for one’s face? And the hands, don’t they reveal things about the past that plastic surgery tries to erase elsewhere?

I was very curious to see what this woman would read in my face, my ankles, and especially in the small mole just over my right eyebrow. But her first words disappointed me.

‘Your ears are indicative of generosity.’ (One of the usual gambits to put the ‘patient’ in a good mood, I said to myself.) ‘Your brothers and sisters all depend on you.’

‘That’s not true – I have no brothers or sisters,’ I replied aloud. ‘I’m an only child.’

She was unperturbed. ‘If there are no brothers and sisters, then it’s your relatives. Your ears say that many of your relatives depend on you.’ (Yes and no, I said to myself, already resigned to more of these generalities.)

‘As a young man you had great problems over money and health, but since the age of thirty-five everything has gone well from that point of view. You’re fortunate, because you have always had beside you someone you trust, someone who helps you.’

‘Yes, indeed. I’ve been married for over thirty years,’ I said.

‘Yes, and you married your second love, not the first.’ (Not true at all – neither the first nor the second – but by now I had already given up hope of hearing anything interesting, and did not want to disappoint the lady.)

‘Your ears indicate that one day you’ll come into a great inheritance from your parents.’ (Poor ears, they lie! From my parents – my father died some time ago – nothing of that sort can be expected. Certainly if today I asked my mother – eighty-five years old and affected by senile dementia – ‘Mother, where have you hidden the money?’ she would raise a hand and, with that splendid smile that is party to the things she no longer knows, would say, ‘Over there…over there’, indicating with absolute confidence some point in the air. Well, that money ‘over there’ is all I will ever inherit. Or should I reinterpret the word ‘inheritance’, taking it to mean not only money?)

The woman continued, ‘In the house where you live is a place where you worship the gods and your ancestors. It’s good that you do this. Never give it up.’ (Ah, now this is interesting. In the home of every Asian, especially the Chinese, there is a place of that sort, usually a little altar, and it takes no great powers of second sight to imagine this. It is like telling a devout Christian: ‘There’s a crucifix in your house.’ But this woman can see that I am a foreigner, in all probability not a Buddhist and certainly not given to ancestor-worship. And yet she says this – and she is right. In my house there is just such a place. It came into being over the years. I had become interested in those gilded camphorwood statuettes that the southern Chinese have on their family altars, and I had bought a few in Macao. After a while, seeing them sitting on my shelves like ornaments, I had a feeling that they were suffering, removed from their altars, that they had lost their meaning. I began putting sticks of incense beside them. Then in Peking, in an old second-hand shop near the Drum Tower where I used to drop in now and then to see what the peasants had brought to sell, I saw a beautiful altar of carved wood, one of those on which families used to keep little votive tablets for their ancestors, and I bought it. The Macao statues now had a home; and when my father died his photograph came to rest in the lap of a fine Buddha who by then occupied the centre of the altar. Since then, every day I light a stick of incense, and with that little rite take a moment to remember him. He is buried in a big cemetery in Florence, one of those where you get lost in the maze of alleys and paths, and where every grave is exactly like all the others. I have never wanted to go there. His place for me is in my home, on that Chinese ancestral altar.)

‘The house you live in, in Thailand, is in a beautiful place that makes you happy. Stay in that house as long as you are in this country.’

Again she studied my face, pondered, and said that money melts in my hand. (Well, there is a consensus on that, at least.) She said that I tend to be lucky, that I have instinct, that where the road forks I always choose the direction that turns out best, and that I always surround myself with the right people. She said that my mouth does not indicate regrets because in life I have always done what I wanted. ‘You will have a long life,’ she proclaimed. Then she focused on my mole. ‘Ah, this is a sign of your good luck, but it’s also a sign that you’ll die abroad.’ She paused a moment and added: ‘There is no doubt about it: you’ll die in a country which is not your own.’

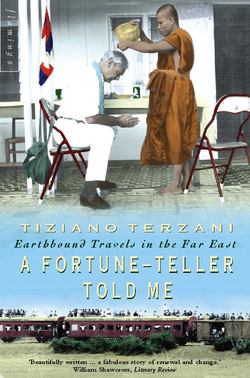

She asked if I had any questions. I tried to think of one, and remembered that in the autumn the English and German editions of my latest book, the story of a long journey through the Soviet Union in the months when the empire fell apart and Communism died, would be published.

‘What should I do to ensure that this book will be successful and sell lots of copies?’ I asked.

She concentrated, then replied with an air of complete certainty: ‘The book must come out between 9 September and 10 October; it must be neither too long nor too short; it must have a coloured dustjacket, but the colours must not be too strong; and, above all, in the title there must be the name of a person, but not that of a woman.’

I burst out laughing, glad that Vladimir Ilyich was born male. The book was called Goodnight, Mister Lenin, and the dustjacket, long decided upon, was in pastel colours.

She concluded: ‘And don’t forget that you must pray to Buddha and make offerings on the altar of your ancestors. Only if you do that will the book enjoy success!’

She did not ask for payment, only that I make a contribution to the Association.

I spent several days reflecting on my decision not to fly and trying to analyze the real reasons behind it. There could be no denying that I wanted to do something different, to have an excuse for a change in the daily routine. But had I not also thought that by obeying the Hong Kong fortune-teller’s injunction I would avoid the possibility of that air accident about which he had been so emphatic? That was obviously so, but I found it hard to admit.

I realized that despite having lived many years in Asia, and having adapted myself to the life there, intellectually I still had my roots in Europe. I had not expunged from my mind the instinctive Western contempt for what we call superstition. Every time I found myself starting to feel that way I had to remember that in Asia ‘superstition’ is an essential part of life. And anyway, I told myself, many of the practices that seem absurd today may originally have had a certain logic which with time has been forgotten. For example acupuncture: it works, but no one can really explain why. And the art of feng-shui was originally based on the careful study of nature: the nature which we moderns understand less and less.

In Chinese feng means wind, shui means water. Feng-shui thus means ‘the forces of nature’; the expert in feng-shui is one who understands the fundamental elements of which the world is made, and can judge the influence of one on another. He can evaluate the influence that the course of a river, the position of a hill or the shape of a mountain may have on a city or a house to be built, or a grave to be dug. Strange? Not at all. Even we, in planning a house, take account of the sun’s direction, and make sure the building is not too exposed to dampness.

For many centuries the principles of feng-shui have had a decisive influence on Chinese architecture. The plans of all the ancient settlements of the Celestial Empire, beginning with the one that is now the city of Xian, as well as those of the Chinese diaspora, including Hue, the imperial capital of Vietnam, were based on considerations of feng-shui. The same is true for all the imperial tombs, beginning with that of Qin Shi Huang Di, the first emperor, with his famous terracotta army. The position of a tomb is very important. A grave that is well located and exposed to ‘cosmic breath’ can keep alive the soul of the deceased and bring happiness and well-being to future generations. A badly placed tomb, on the other hand, can bring the descendants misfortune after misfortune.

The art of feng-shui was born in China, but today it is a common practice in much of Asia. When something goes wrong – a marriage, a business deal or a factory – the first thought is that something is out of joint with the feng-shui, and an expert is consulted. A few years ago in Macao a newly opened casino was failing to attract customers. The cause, according to the feng-shui man, lay in the colour of the roof: it was red like the shell of a dead crab, rather than green like the shell of a live one. The roof was repainted and business boomed.

Anecdotes of this kind have cost feng-shui some of its ancient respectability. But they have not reduced its popularity, and there is a growing number of people in Asia today who, on the advice of feng-shui experts, propitiate fate by changing their furniture arrangement, the colour of their office walls or the shape of their front doors. Even the earnest British directors of the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, when they decided to build their big new head office in Hong Kong, turned to one of the best-known experts in the colony to avoid trouble with the feng-shui. During the planning of that futuristic steel and glass edifice the architect, Norman Foster, was constantly in touch with this ‘master of the forces of nature’, taking note of what he said and following his recommendations. These determined a great number of architectural details, including the strange diagonal placement of the entrance stairway.

After building the bank, Foster helped to plan the new Hong Kong airport (in the shape of a dragon!). But people in certain areas of his office were continually falling ill. So the feng-shui expert was called in. He studied the problem, and concluded that the demolition of some old houses in the area had left a gap through which ‘evil spirits’ flew in a direct line to strike the building. For the people working there it was like having a knife constantly plunged in their chests. His advice was to move all the desks, to curtain the windows and to place mirrors to deflect the spirits. Absurd? Perhaps, but once all this was done there were no further complaints from the staff.

Obviously, the ‘successes’ of feng-shui, as of any magic practice, are partly explained by an element of autosuggestion: if people firmly believe that something can help them, it may indeed do so. The typical case is that of a couple, childless for years, who manage to conceive after following the advice of the feng-shui man to change the position of their marital bed.

What is interesting about feng-shui, despite its facade of magic, is its basic principle: the constant re-establishment of harmony with nature. For the Chinese everything has to be in equilibrium. Illnesses, misfortunes, sterility or bad luck result from the rupture of some harmony, and the function of feng-shui is to restore it. Ecologists ante litteram, the Chinese. They knew nature well. They knew nothing else!

The Chinese have never been metaphysicians, they have never believed in a transcendent god. For them nature is all, and it is from nature that they have drawn their knowledge and their beliefs. Even their writing, made up of images, is based on nature and not on some abstract convention like our alphabet. In any European language it would be possible to agree that from now on the word ‘fish’ means horse and the word ‘horse’ means fish. But in Chinese such a thing would be inconceivable, because the character used to write fish is a fish, and the character for horse is a horse.

Western man sees God as the creator of nature, and for centuries has distinguished between the natural world and the world of the divine. But for the Chinese the two are indistinguishable. God and nature are the same thing. Divination is thus a sort of religion, and the fortune-teller is also a theologian and priest. That is why, until the advent of Communism, superstition was never repressed in China as it was in the West, where it was seen as the antithesis of religion and has always been vigorously suppressed. The Chinese – like almost all Asians – have never worried about this distinction between religion and superstition, just as they have never posed the problem – also typically Western – of defining what is and is not science. For centuries the Chinese have practised astrology, for example, without ever wondering if its bases were ‘scientific’. In their eyes it worked, and that was enough.

Chinese astrology is based on the lunar calendar. A year consists of twelve new moons to which, every twelve years, a thirteenth is added. Twelve years make a cycle. Each year is characterized by an animal: the rat, the ox, the tiger, the cat, the dragon, the snake, the horse, the goat, the monkey, the rooster, the dog, the pig. The first day of the year is the day of the first moon and the year always begins in January or February.

The animal of the year of one’s birth has an enormous influence on one’s personality and destiny: people born in the year of the rat, for example, must take care all their lives not to fall into traps; those born in the year of the cat will always land on their feet; those born under the sign of the rooster must always scratch the earth to feed themselves. Women born in the year of the horse are indomitable and therefore difficult wives. Those born in the combination of the horse with fire – which happens every sixty years – are wild, dangerous and practically impossible to marry. 1966 was one of those years, and in Asia many women who found themselves pregnant resorted to abortions to avoid bringing into the world daughters who would not, in all probability, find husbands. In Taiwan in 1966 the birth rate fell by 25 per cent for this reason.

On the other hand, males born in the year of the dragon are destined to be strong, intelligent and fortunate. As 1988 was such a year, coupled with the fact that the Chinese consider the double 8 to be a symbol of double happiness, many couples tried to have sons then. To render the child even more fortunate, many mothers tried to give birth on the eighth day of the eighth month of that year: all the maternity beds in Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong were booked up by women prepared to undergo Caesarean sections to bring their children into the world on that ultra-auspicious day – 8 August 1988.

One of the most important factors determining a person’s destiny is the exact hour of his birth. Only by knowing that hour can the astrologer draw his horoscope, identify his character, describe the important stages of his life and even foresee the eventual date of his death. To know the hour of someone’s birth is to possess a weapon against him; therefore many politicians in Asia keep their birth-hour secret, or give a false one.

Everyone knows that Deng Xiaoping was born on 22 August 1904 (the year of the dragon!), but the exact hour remains one of China’s great secrets. Mao Tse-Tung and Chou Enlai were less successful. In the 1920s both of them, then living in Shanghai, went – as a joke, or because they believed in it, who knows? – to see the most famous astrologer of the city, a certain Yuan Shu Shuan. When the nationalists fled to Taiwan in 1949, among the piles of documents they took with them were the horoscopes that Master Yuan had carefully preserved of all his clients. Those of people who had since become famous were published. In 1962 a Taiwanese astrologer predicted, on the basis of the birth times given to Yuan, that both Mao and Chou would die in the same year, 1976. And indeed they did.

Innumerable political decisions in Asia are based on astrology, and therefore the secret services of various countries employ experts to predict what their adversaries’ astrologers may advise in certain situations. It is known that the Vietnamese, the Indians, the South Koreans and the Chinese have astrology sections in their counter-espionage agencies. Even the British have one, based in Hong Kong, to keep track of what the Chinese are doing in the sphere of the occult. Increasingly, it seems, all sorts of old practices, banned during forty years of Communism, have now resurfaced to flourish not only among the people, but among the Communist rulers themselves.

In 1990, a few days before the anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre, a strange thing happened. A group of workers erected a large ring of scaffolding around the flagpole in the centre of the square and started working inside it. When the scaffolding was removed, the height of the pole had been increased by a few yards, and the red flag, symbol of China, flew higher than it had ever done since 1949. Apparently a great feng-shui expert had suggested to Deng Xiaoping that this would restore the harmony of the square and thus the good fortune of the People’s Republic.

I began collecting stories like these because I planned to write an article on the importance of superstition in Asia, but I also wanted to dispel my doubts and to convince myself that I was right to change my life for a reason that had absolutely nothing rational about it. But was that not true of much of the life around me? Especially in Thailand, I had only to use my eyes.

In Thailand it is common for important political declarations to be made on days considered auspicious, and for politicians to reassure public opinion about the state of the economy or national security by quoting astrologers. In the middle of the Gulf War, when Thailand feared attacks from Islamic terrorists because of its pro-American stance, Prime Minister Chatichai called a press conference and said: ‘There is nothing to worry about. Thailand will be spared. My astrologer says so.’ Nobody laughed. Everyone knew that he was serious. A couple of months previously he had had a mole removed from under his left eye because his astrologer had told him it would bring him bad luck.

In February 1991 Chatichai was overthrown by one of the usual military coups, but after a few months of peaceful exile in London he came back to live in Bangkok. Even in that coup, the occult seems to have played no small role. The generals who seized power had just returned from a secret trip to Burma. In Rangoon they had made offerings in the temple where their Burmese colleagues had made theirs before their successful coup of 1988. Then, taking care not to ‘discharge’ their energy – which meant never touching the earth, always walking on a red carpet – they went to the car, to the helicopter, to the plane, and at last to the Bangkok general command post. There, still ‘charged’, they launched their putsch, the success of which many in Bangkok believed was due to the Burmese energy.

A year after the coup, General Suchinda, who had become Prime Minister, gave the army orders to fire on a crowd of demonstrators. There were several hundred victims. The crisis was resolved by the intervention of the king. General Suchinda resigned, but not before declaring a general amnesty, thanks to which he and the others responsible for the massacre were granted immunity from any legal action. The deaths, said Suchinda, could not be laid at his door: it had been the demonstrators’ karma to die. Most people let it go at that, but a group of implacable democrats found it intolerable that no one should be punished for the deaths of so many people. For justice they turned to black magic.

One Sunday morning, on the great Sanam Luang Square in front of the Royal Palace, a strange ceremony took place. The names and photographs of Suchinda and the other two generals of the junta were placed in an old coffin, and the widows of some of the victims burned peppers and salt in broken begging bowls. Coffins, widows and broken crockery are symbols of great misfortune, and the ceremony was meant to put the evil eye on the three generals and destroy them.

The generals took the matter very seriously. Suchinda went to a famous monk to have his name changed, so that the evil eye would fall on the one he no longer bore; one of the other generals, also on the advice of a monk, changed his spectacle frames, shaved off his moustache and ate a piece of gold leaf so as to make his speeches more popular; the third had a surgeon remove some wrinkles that were bringing him bad luck, and then, to be on the safe side, took his mistress and went to Paris to run a restaurant.

No history book, especially if written by a foreigner, will ever give that version of the coup and the Bangkok massacre. But that is how most people in Thailand experienced them.

One encounter that greatly encouraged me to hold to my plan was with some researchers at the Ecole Francaise de l’Extreme Orient. For the first time in its history the school had organized a meeting of all its scholars, in Thailand. I went to hear about their work and discovered, to my great surprise, that some of them were studying the subjects in which I had become interested.

One ethnologist gave a paper investigating the revival of occult Taoist practices in the Chinese province of Fukien. He told how one night, under a full moon, he had witnessed a ceremony in which a man immobilized by ropes had suddenly shot like an arrow across the rice fields, drawing after him the whole population of the village, including the local Communist Party secretary.

The story resembled some of those recounted by Alexandra David-Neel about Tibet in the 1930s. Only this was China in 1993, and the narrator was a scholar who could hardly be suspected of exaggeration.

There was something in the air that told me I had made the right decision.