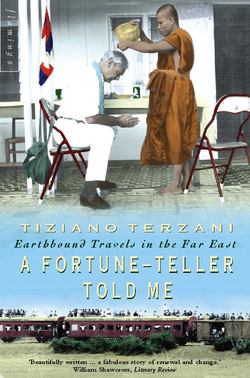

Читать книгу A Fortune-Teller Told Me: Earthbound Travels in the Far East - Tiziano Terzani - Страница 9

CHAPTER FIVE Farewell, Burma

ОглавлениеIn January I heard that the Burmese authorities at the frontier post of Tachileck, north of the Thai town of Chiang Mai, had begun issuing some entry visas ‘to facilitate tourism’. You had to leave your passport at the border and pay a certain sum in dollars, after which you were free to spend three days in Burma and travel as far as Kengtung, the ancient mythical city of the Shan.

This scheme was obviously dreamed up by some local military commander to harvest some hard currency, but it was just what I was after. I was looking for something to write about without having to use planes, and this was an interesting subject: a region which no foreign traveller had succeeded in penetrating for almost half a century was suddenly opening up. By pretending to be a tourist I could again set foot in Burma, a country from which as a journalist I had been banned.

In Tachileck the Burmese had probably not yet installed a computer with their list of ‘undesirables’, so Angela and I, together with Charles Antoine de Nerciat, an old colleague from the Agence France Press, decided to try our luck. We came back with a distressing story to tell: the political prisoners of the military dictatorship, condemned to forced labour, were dying in their hundreds. We brought back photographs of young men in chains, carrying tree trunks and breaking stones on a riverbed. Thanks to that short trip we were able to draw the attention of public opinion to an aspect of the Burmese drama which otherwise would have passed unobserved. And I had gone there by chance – or rather because of a fortune-teller who told me not to fly.

This is one aspect of a reporter’s job that never ceases to fascinate and disturb me: facts that go unreported do not exist. How many massacres, how many earthquakes happen in the world, how many ships sink, how many volcanoes erupt, and how many people are persecuted, tortured and killed. Yet if no one is there to see, to write, to take a photograph, it is as if these facts had never occurred, this suffering has no importance, no place in history. Because history exists only if someone relates it. It is sad, but such is life; and perhaps it is precisely this idea – the idea that with every little description of a thing observed one can leave a seed in the soil of memory – that keeps me tied to my profession.

The two towns of Mae Sai in Thailand and Tachileck in Burma are linked by a little bridge. As I crossed it with Angela and Charles Antoine, I felt once again that tremor of excitement, so pleasing but rarer as time goes on, of setting foot where few had been and where perhaps I might discover something. This had been a forbidden frontier at one time. There was said to be a heroin refinery just a few dozen yards inside Burmese territory. With good binoculars, you could make out a sign in English: ‘Foreigners, keep away. Anyone passing this point risks being shot.’ Now in its place is one proclaiming in big gold letters: ‘Tourists! Welcome to Burma!’

So, Burma too has yielded to the common fate. For thirty years it tried to resist by remaining isolated and going its own way, but it did not succeed. No country can, it would seem. From Mao’s China to Gandhi’s India to Pol Pot’s Cambodia, all the experiments in autarchy, in non-capitalist development with national characteristics, have failed. And what is more, most have left millions of victims.

At least the Burmese experiment had a fine name. It was called ‘the Buddhist way to socialism’. This was the invention of General Ne Win, who took power in 1962 and imposed a military dictatorship. He tried to spare Burma the severity of the Communist regime that ruled China on the one hand, and the American-style materialist influence that was taking root in Thailand on the other. Ne Win closed the country, nationalized its commerce and imprisoned his opponents, claiming that only in that way could Burmese civilization be protected. In a certain sense he was right, and ultimately this bestowed legitimacy on his dictatorship. In Ne Win’s hands Burma did indeed preserve its identity. The old traditions survived, religion flourished, and the way of life of the forty-five million inhabitants was not thrown into confusion by industrialization, urbanization and mindless aping of the West. By these means a country like Thailand has indeed been developed, but it has also been traumatized.

The Rangoon authorities did not want too many foreigners to ‘pollute the atmosphere’; they doled out visas sparingly, allowing only seven-day visits. Those who went there came back feeling that they had seen a country still untouched by influences from the rest of the world. Burma was a fascinating piece of old Asia, a land where men still wear the longyi, a sort of skirt woven locally; where even women smoke the cheroot, strong green cigars rolled by hand, and not Marlboros; a land where Buddhism is still a living faith and the beautiful old pagodas are still places of living worship, not museums for tourists to stroll around.

That Burma is now about to disappear, too. After a quarter of a century of uncontested power, Ne Win handed over the reins to a new generation of military men, who have imposed a dictatorship more brazen, more violent and murderous, but also more ‘modern’, than the former paternalistic one.

One had only to walk through the market in Tachileck to see that the new generals who are now the masters in Rangoon have dropped all pretence of following ‘a Burmese path’. They have decided to put a stop to the country’s isolation, and have adopted as a model of development the one that for decades has been knocking at their door, as at those of the Laotians, the Khmer and now the Vietnamese: Thailand.

Tachileck has already lost its Burmese patina. It has fourteen casinos and numerous karaoke bars. Heroin is on sale more or less openly. The largest restaurant, two discotheques and the first supermarket are owned by Thais. No transaction takes place in the local currency, the kyat. Even in the market the money they all want is that of Bangkok, the baht.

It is the military and the police who organize tourist visas, who change dollars, who procure a jeep, a driver and an interpreter. I took it for granted that the interpreter assigned to me was a spy, and I managed to get rid of him by offering him three days’ paid holiday. In the market I had been approached by a man of about fifty who seemed more trustworthy. He was a Karen – a member of an ethnic minority hostile to the Burmese; a Protestant, and hence used to Western modes of thought; and he spoke excellent English. Meeting him was a rare piece of luck, because Andrew – a name given him by American missionaries – was a mine of information and explanations.

‘Why are the hills so bare?’ I asked as soon as we left Tachileck.

‘The Thais have cut down the forests.’

‘Whose houses are those?’ I enquired at the first village we came to, where several new dwellings stood out glaringly among the old dark wooden ones.

‘They belong to families who have daughters working in the brothels in Thailand.’

‘And those cars?’

‘They are on the way from Singapore to China. The Wa, they’re no longer headhunters. They’re smugglers.’

‘In heroin?’

‘Only in part. Here in the south they’re in competition with Khun Sa, the real drug king.’

We drove into the mountains, which still looked as if they were hiding a thousand mysteries. In the old maps this part of the world was labelled the ‘Shan States’ because the Shan, who came from China in the twelfth century to escape the advancing Mongols, formed the bulk of the population. The whole region was a sort of living museum of the most varied humanity. Apart from the Shan there were dozens of other tribes living there, each with its own language, its own customs and traditions, its own way of farming and hunting. The encounter with these different groups, of which the Pao’, Meo, Karen and Wa tribes became the best known, was one of the great surprises that greeted the first European explorers in the region.

The long necks of the ‘giraffe women’ of the Padaung, like the tiny bound feet of Chinese women, exemplified Asia’s bizarre aberrations. Even today, the Padaung judge a woman’s beauty by the length of her neck. From birth every girl has big silver rings forced under her chin. By the time she is old enough to marry her head will be sixteen to twenty inches above her shoulders, supported by a stack of these precious collars. If they were removed she would die of suffocation: her head would fall to one side and her breathing would be cut off.

For centuries the Shan have resisted every attempt on the part of the Burmese to dominate them, and have managed to stay independent. The British too, when at the end of the nineteenth century they arrived from India to extend their colonial power, recognized the authority of the thirty-three sawbaws, the Shan kings, and left them to administer their rural dominions, which bore names like ‘the Kingdom of a Thousand Banana Trees’.

In 1938 Maurice Collis, a sometime colonial administrator who became a writer, visited the Shan States and tried to bring to the attention of the British public this unknown wonder of the Empire. Kengtung, with its thirty-two monasteries, struck him as a pearl, and he found it absurd that no one in London seemed to have heard of it. The book he wrote, The Lords of the Sunset – as the sawbaws were called, to distinguish them from the ‘Lords of the Dawn’, the kings of western Burma – is the last testimony of a traveller in that uncontaminated world of peasant kings, where life had been the same for centuries, its rhythm that of old ceremonies, its rules those of feudal ties. I had brought that fifty-five-year-old book with me as a guide.

The road that took us to Kengtung was in places little more than a cart track, barely ten feet wide and full of potholes, often perilously skirting the edge of a precipice, but it was obviously of recent construction.

‘Who built it?’ I asked Andrew.

‘You’ll see them soon.’ Andrew had realized that we were not normal tourists, but that did not seem to worry him. Quite the contrary.

After a few miles Andrew told the driver to stop near a pile of timber at the side of the road. We had scarcely got out of the jeep than we heard a strange clanking sound from the brushwood, like chains being dragged. Yes – chains they were. They were around the ankles of about twenty emaciated ghosts of men, some shaking with fever, all in dusty rags, moving wearily in unison like an enormous centipede, with a long tree trunk on their shoulders. The chains on their feet were joined to another around their waists.

The two soldiers accompanying the prisoners made us a sign with their rifles to drop our cameras.

‘They’re missionaries. Don’t worry,’ said Andrew. It worked. A couple of cigarettes added conviction.

The prisoners put down the trunk and stopped. One of them said he was from Pegu, another from Mandalay. Both had been arrested five years before, during the great demonstrations for democracy: political prisoners, doing forced labour.

It is strange to stand before such an atrocity, be obliged to take mental notes and discreetly snap a few photos, trying to avoid risks and not to give those poor devils more problems than they already had; and then to realize that you have not even had the time to feel compassion, to exchange a word of simple humanity. You suddenly find yourself looking into an abyss of pain, you try to imagine its depths, and all you can think of asking is, ‘And those?’ pointing to the chains.

‘I’ve had them on for two years. One more and I’ll be able to take them off,’ said the young man from Pegu. He was one of the lucky ones: he was wearing a pair of old socks that slightly mitigated the contact of the iron rings with his flesh. Others, lacking such protection, had ugly wounds on their ankles.

‘And malaria?’

‘Lots,’ said the young man from Mandalay, turning mechanically to his neighbour, who was shaking, yellow and puffy-faced. His bony hands were covered in strange stains, like burns. The prisoners – about a hundred in all – lived in a field not far away. Soon we were to see their companions, also chained, breaking stones on the riverbed. These too were guarded by armed soldiers, who would not allow us to stop.

Since the coup in 1988, the massacre of the demonstrators and the arrest of the heroine of the pro-democracy struggle Aung San Suu Kyi, the Rangoon dictators have continued to terrorize the country and to stifle any expression of dissent at birth. Tens of thousands, especially young people, have been arrested and sent to forced labour, used as porters in the army or in fields mined by the guerrillas. Political prisoners are thrown in with common criminals in this forgotten tropical gulag.

‘There are camps like this everywhere,’ Andrew said. ‘Private firms acquire contracts for road-building, and go to the prisons for the men they need. If they die they go back and take some more.’ He had heard that to build the 103 miles of road from Tachileck to Kengtung several hundred men had already died.

It took us seven hours to cover those 103 miles, but by the time we arrived in Kengtung the use of that road was clear to us: it was Burma’s road to the future. Though its original purpose had been to finance the dictatorship and to provide an umbilical cord linking Burma with the neighbouring countries that shared its goals – China and Thailand – by now the road lived by a logic of its own, and served all sorts of people for all sorts of traffic. Communist ex-guerrillas, recently converted to opium cultivation, use it to move consignments of drugs; the Wa, former headhunters, to smuggle cars, jade and antiques; Thai gangsters to top up their supply of prostitutes with young Burmese girls. Thanks to its isolation Burma has, so far, staved off the AIDS epidemic, so these girls, often only thirteen or fourteen years old, are in great demand for the Thai brothels, where thousands of them are already working. At the end of 1992 about a hundred who tested HIV positive were expelled and sent home. Rumour has it that the Burmese military killed them with strychnine injections.

We arrived in Kengtung at sunset. After many miles of tiresome ascents and descents, through narrow gorges between monotonous mountains where the eye never had the relief of distance, we suddenly found ourselves in a vast, airy valley. In the middle of it white pagodas, wooden houses and the dark green contours of great rain trees were silhouetted like paper cutouts against a background of mist that glowed first pink and then gold in the setting sun. Kengtung was evanescent, incorporeal like the memory of a dream, a vision outside time. We stopped; and perhaps, from the distance, we saw the Kengtung of centuries ago, when the four brothers of the legend drained the lake that once filled the valley, built the city, and erected the first pagoda. There they placed the eight hairs of Buddha, which the Great Teacher had left when passing through.

The town was at supper. Through the open doorways of the shop-houses, with dogs on the thresholds, we could see families sitting around their tables. Oil lamps cast great shadows on walls dotted with photographs, calendars and sacred images. There was no traffic on the streets; the air was filled with the quiet murmur of evening’s isolated voices and distant calls.

A fair was in progress in the courtyard of a pagoda. People crowded around the many stalls, lit by small acetylene lamps, to buy sweets and to gamble with large dice that had figures of animals instead of numbers. Wide-eyed children peered through the forest of hands holding out bets to the peasant croupiers. In the shadows, at the feet of three large Buddhas smiling timidly in bronze, a group of the faithful were gathered in meditation. Some women, their long hair gathered in off-centre chignons, had lit fires on the pavements and were cooking sugared rice in large bamboo canes.

There was nothing physically breathtaking about Kengtung – no particularly impressive monument, temple or palace. Its touching charm lay in its atmosphere, in its tranquillity, in the timeless pace of life without stress.

Is it strange to find all this beautiful? Is it absurd to worry that it is changing? In appearance everything is fine these days in Asia. The wars are over, and peace – even ideological peace – reigns, with very few exceptions, over the whole continent. Everywhere people speak of nothing but economic growth. And yet this great, ancient world of diversity is about to succumb. The Trojan horse is ‘modernization’.

I find it tragic to see this continent so gaily committing suicide. But nobody talks about it, nobody protests – least of all the Asians. In the past, when Europe was beating at the doors of Asia, firing cannonballs from her gunboats and seeking to open ports, to obtain concessions and colonies, when her soldiers were disdainfully sacking and burning the Summer Palace in Peking, the Asians, one way or another, resisted.

The Vietnamese began their war of liberation the moment the first French troops landed on their territory; that war lasted more than a hundred years, and only ended with the fall of Saigon in 1975. The Chinese fought in the Opium Wars, and in the end trusted to time to free themselves from the foreigners who ruled with the force of their more efficient weapons. (The last two pieces of Chinese territory still in foreign hands, Hong Kong and Macao, are returning to Peking’s sovereignty in 1997 and 1999 respectively.)

Japan, on the other hand, reacted like a chameleon. It made itself externally Western, copied everything it could from the West – from students’ uniforms to cannons, from the architecture of railway stations to the idea of the state – but inwardly strove to become more and more Japanese, inculcating in its people the idea of their uniqueness.

One after another the countries of Asia have managed to free themselves from the colonial yoke and show the West the door. But now the West is climbing back in by the window and conquering Asia at last, no longer taking over its territories, but its soul. It is doing it without any plan, without any specific political will, but by a process of poisoning for which no antidote has yet been discovered: the notion of modernity. We have convinced the Asians that only by being modern can they survive, and that the only way of being modern is ours, the Western way.

Projecting itself as the only true model of human progress, the West has managed to give a massive inferiority complex to those who are not ‘modern’ in its image – not even Christianity ever accomplished this! And now Asia is dumping all that was its own in order to adopt all that is Western, whether in its original form or in its local imitations, be they Japanese, Thai or Singaporean.

Copying what is ‘new’ and ‘modern’ has become an obsession, a fever for which there is no remedy. In Peking they are knocking down the last courtyard houses; in the villages of South-East Asia, in Indonesia as in Laos, at the first sign of prosperity the lovely local materials are rejected in favour of synthetic ones. Thatched roofs are out, corrugated iron is in, and never mind if the houses get as hot as ovens, and if in the rainy season they are like drums inside which the occupants are deafened.

So it is with everyone these days. Even the Chinese. Once so proud to be the heirs of a four-thousand-year-old culture, and convinced of their spiritual superiority to all others, they too have capitulated; significantly, they are beginning to find it embarrassing still to eat with chopsticks. They too feel more presentable with a knife and fork in their hands, more elegant if dressed in jacket and tie. The tie! Originally a Mongol invention for dragging prisoners tied to the pommels of their saddles…

By now no Asian culture can hold out against the trend. There are no more principles or ideals capable of challenging this ‘modernity’. Development is a dogma; progress at all costs is an order against which there can be no appeal. Merely to question the route taken, its morality, its consequences, has become impossible in Asia.

Here there is not even an equivalent of the hippies who, realizing there was something wrong with ‘progress’, cried ‘Stop the world, I want to get off!’ And yet the problem exists, and it is everyone’s. We should all ask ourselves – always – if what we are doing improves and enriches our lives. Or have we all, through some monstrous deformation, lost the instinct for what life should be: first and foremost, an opportunity to be happy. Are the inhabitants happier today, gathered in families chatting over supper, or will they be happier when they too spend their evenings mute and stupefied in front of a television screen? I am well aware that if we were to ask them, they would say that in front of a television is better! And that is precisely why I should like to see at least a place like Kengtung ruled by a philosopher-king, by an enlightened monk, by some visionary who would seek a middle way between isolation cum stagnation and openness cum destruction, rather than by the generals now holding Burma’s fate in their hands. The irony is that it was a dictatorship that preserved Burma’s identity, and now another dictatorship is destroying it and turning the country, which had so far escaped the epidemic of greed, into an ugly copy of Thailand. Would Aung San Suu Kyi and her democratic followers be any different? Probably not. Probably they too wish only for ‘development’. They too, if they ever came to power, could only allow the people that freedom of choice which in the end leaves them with no choice at all. No one, it seems, can protect them from the future.

Night fell in Kengtung, timeless night, a blanket of ancient darkness and silence. All that remained was a quiet tinkling of bells stirred by the wind at the top of the great stupa of the Eight Hairs. Led by this sound we climbed the hill by the light of the moon, which, almost full, rimmed the white buildings in silver. We found an open door, and spent hours talking with the monks, sitting on the beautiful floral tiles of the Wat Zom Kam, the Monastery of the Golden Hill. That afternoon several lorries had arrived from the countryside full of very young novices. Accompanied by their families, they were all sleeping on the ground along the walls, at the feet of large Buddhas with their faint, mysterious smiles, that glimmered in the light of little flames. Statues though they were, they were dressed in the orange tunic of the monks, exactly as if they too were alive and had to be shielded from the night breeze that came in at the windows. The novices, small shaven-headed boys of about ten, lay wrapped in new saffron-coloured blankets given them by their relatives for the initiation. For years to come the pagoda would be their school – a school of reading, writing and faith, but also of traditions, customs and ancient principles.

What a difference, I thought, between growing up that way – educated in the spartan order of a temple, beneath those Buddhas, teachers of tolerance, with the sound of the bells in their ears – and growing up in a city like Bangkok where children nowadays go to school with a kerchief over their mouths to protect them from traffic fumes, and with Walkmans plugged in their ears to drown out the traffic noise with rock music. What disparate men must be created by these disparate conditions. Which are better?

The monks were interested in talking about politics. They were all Shan, and hated the Burmese. Two of them were great sympathizers of Khun Sa, the ‘drug king’, but now also the champion in the struggle for the ‘liberation’ of this people which feels oppressed.

In 1948, under pressure from the English, the Shan, like all the other minority populations, consented to become part of a new independent state, the Burmese Union, with the guarantee that if they chose they could secede during the first ten years. But the Burmese took advantage of this to wipe out the sawbaw and reinforce their control over the Shan States. Secession became impossible, and ever since there has been a state of war between the Shan and the Burmese. Here the Rangoon army is seen as an army of occupation, and often behaves like one. In 1991 some hundreds of Burmese soldiers occupied the centre of Kengtung and razed the palace of the sawbaws to the ground, claiming the space was needed for a tourist hotel. The truth is that they wanted to eliminate one of the symbols of Shan independence. In that palace had lived the last direct descendant of the city’s founder. His dynasty had lasted seven hundred years. Old photographs of that palace now circulate clandestinely among the people, like those of the Dalai Lama in Lhasa.

When we left the pagoda it was still a couple of hours before dawn, but along the main street of Kengtung a silent procession of extraordinary figures was already under way. Passing in single file, they seemed to have come out of an old anthropology book: women carrying huge baskets on long poles supported by wooden yokes across their shoulders; men carrying bunches of ducks by the feet; more women, moving along with a dancing gait to match the movement of the poles. The groups were dressed in different colours and different styles: Akka women in miniskirts with black leggings and strange headgear covered with coins and little silver balls; Padaung giraffe-women with their long necks propped up on silver rings; Meo women in red and blue embroidered bodices; and men with long rudimentary rifles. These were mountain people who had come to queue for the six o’clock opening of one of Asia’s last, fascinating markets.

Sitting on the wooden stools of the Honey Tea House we had breakfast – some very greasy fritters, which a young man deftly plucked with bare hands from a cauldron of boiling oil. We dunked them in condensed milk. Among the soldiers and traders at the other tables on the pavement, Andrew saw a friend of his, the son of a local lordling of the Lua’ tribe, and invited him to join us. People continued to file past on their way to the market. We saw some men dressed entirely in black, each with a big machete in a bamboo sheath at his side. ‘Those are the Wa, the wild Wa,’ Andrew’s friend informed us with a certain disgust. ‘They never part from their big knives.’

He told us that since he was small his father had taught him to be extremely careful of these Wa. Unlike the ‘civilized’ Wa, these had remained true to their traditions, and they still really cut people’s heads off. Shortly before the harvest, when their fields are full of ripe rice, the wild Wa make forays into their neighbours’ lands, capture someone – preferably a child – and with the same scythe that they later use for the harvest, cut off his head. ‘They bury it in their fields as an offering to the rice goddess. It’s their way of auguring a good harvest,’ said the young man. ‘They’re dangerous only when they go outside their own territory. At home they don’t harm anyone. If you go and visit them they are very kind and hospitable. You only have to be careful of what they give you to eat!’ At times, he said, someone invited to dinner by the Wa finds a piece of tattooed meat on his plate. In a word, it would seem that the Wa are also cannibals – at least if you take the word of their neighbours, the Lua’.

I asked Andrew and his friend to help me find a fortune-teller. Divination is a widely practised art in Burma. It is said that the Burmese, geographically placed between China and India – the two great sources of this tradition – have been especially skilled in combining the occult wisdom of their two neighbours, and that their practitioners possess great powers. Superstition has played an enormous role in the history of the whole region. It was the Burmese king’s hankering after one of the King of Siam’s seven white elephants, very rare and therefore magical – that sparked off a war which lasted nearly three hundred years – the upshot being that Auydhya was destroyed and the Siamese had to build a new capital, present-day Bangkok.

Even in recent times, astrology and occult practices have been crucial in the life of Ne Win and the survival of his dictatorship. One of the first things you notice on arriving in Burma is that the local currency, the kyat, is issued in notes of strange denominations: forty-five, seventy-five, ninety. These numbers, all multiples of three, were considered highly auspicious by Ne Win, and the Central Bank had to comply.

Like the Thais, the Burmese believe that fate is not ineluctable, that even if a misfortune is forecast it can be averted: not only by acquiring merits, but also by bringing about an event which is similar in appearance to the predicted calamity, thereby satisfying the requirements of destiny, so to speak. Ne Win was a master of this art. He was once told that the country would soon be struck by a terrible famine. He lost no time: he issued orders that for three days all state officials and their families should eat only a poor soup made of banana-tree sprouts. The idea was that by acting out a famine they would avoid the real one – a calamity which in the event never materialized.

On another occasion, Ne Win was told by one of his trusted astrologers to beware of a grave danger: a sudden right-wing uprising which would lead to his deposition. Ne Win gave orders that everyone in Burma immediately had to drive on the right-hand side of the road rather than on the left, as had been the rule since British times. The whole country was thrown into confusion, but this ‘right-wing uprising’ fulfilled the prophecy after a fashion, and the real revolt was averted.

In 1988 the same astrologer warned Ne Win that Burma was on the eve of a great catastrophe: the streets of the capital would run with blood and he would be forced to flee the country. Shortly afterwards, thousands of students were massacred and the streets of Rangoon really did run with blood. Ne Win feared that the second part of the prophecy might also come true. He had to find a way out, and the astrologer suggested it: in Burmese, as in English, the verbs ‘to flee’ and ‘to fly’ are similar. The president would not have to flee if, dressed like one of the great kings of the past and mounted on a white horse, he could succeed in flying to the remotest parts of the country. Nothing simpler! He got hold of a wooden horse (a real one would have been too dangerous), had it painted white and loaded it on to a plane. Dressed as an ancient king, he climbed into the saddle and flew to the four corners of Burma. The stratagem succeeded, and Ne Win was not forced to flee. He is still a charismatic figure behind the scenes, the eminence grise of the new dictatorship.

The new rulers too have their advisory fortune-tellers. Not long ago one of the generals was warned by an astrologer that he would soon be the victim of an assassination attempt. He immediately ordered a public announcement of his death, and so no one tried to kill him any more.

Obviously the reason why the famine, the right-wing uprising, the expulsion of the president and the assassination attempt did not happen was – how shall I put it? – that they were not going to happen, not that they were averted thanks to prophecies. But that is not the logic by which the Asians – especially the Burmese – look on life. Prescience is in itself creation. An event, once announced, exists. It is fact, and although it is still to come it is more real and more significant than something that has already happened. In Asia, the future is much more important than the past, and much more energy is devoted to prophecy than to history.

I had been told in Bangkok that there used to be an old Catholic mission in Kengtung, and that perhaps there were still some Italian nuns living there. We climbed up the hill to the church at dusk. A night light was burning at the feet of a plaster Madonna, and in the refectory young Burmese nuns were clearing the rows of tables after supper. I told one of them who I was and she rushed off, shouting: ‘There are some Italians here! Come…come!’ Down a wooden stairway came two diminutive old women, pale and excited. They wore voluminous grey habits and veils with a little starched trimming. They were beside themselves with joy. ‘It’s a miracle!’ one of them kept repeating. The other said things I could not understand. One was ninety years old, the other eighty-six. We stayed and chatted for a couple of hours. Their story, and that of the Catholic mission in Kengtung, was of a kind that we have lost the habit of telling. Perhaps it is because the protagonists were extraordinary people, and today’s world seems more interested in glorifying the banal and promoting the commonplace types with whom all can identify.

The story begins in the early years of this century. The Papacy, convinced that it would never manage to convert the Shans, highly civilized and devout followers of the Dharma (the way of the Buddha), saw instead a chance of making conversions among the primitive animist tribes of the region, thereby planting a Christian seed in Buddhist soil. The first missionary arrived in Kengtung in 1912. He was Father Bonetta of the Vatican Institute for Foreign Missionaries, a Milanese. He brought little money, but with that he managed to buy the entire peak of one of the two hills overlooking the city. It was there that they hanged brigands on market days, and the land was worthless: too full of phii.

Bonetta was soon joined by other missionaries, and in a short time they built a church and a seminary. In 1916 the first nuns arrived, all from Milan or thereabouts, all in the Order of the Child Mary. An orphanage and a school were opened, later a hospital and a leprosarium. As the years went by, Kengtung was caught up in the political upheavals of the region, and troops of several armies passed through it as conquerors: the Japanese, the Siamese, the Chinese of the Kuomintang and then those of Mao. Last came the Burmese; but the Italian mission is still there.

Today nothing has changed on the ‘Hill of the Spirits’: the buildings are all there, well kept and full of children. Father Bonetta died in 1949, and with other missionaries who never returned to Italy, he lies in the cemetery behind the church. Five Italian nuns remain: three in the hospital, and the two oldest in the convent, together with the local novices.

‘When I first came here you couldn’t go out at night because there were tigers about,’ said the oldest, Giuseppa Manzoni, who has been in Kengtung since 1929 and has never gone back to Italy. Speaking Italian does not come easily to her. She understands my questions, but most of the time she answers in Shan, which a young Karen sister translates into English.

Sister Giuseppa was born in Cernusco. ‘A beautiful place, you know, near Milan. I always went there on foot because there was no money at home.’ Her parents were peasants. They had had nine children, but the seven sons all died very young and only she and her sister survived.

Sister Vittoria Ongaro arrived in Kengtung in 1935. ‘On 22 February,’ she says, with the precision of someone remembering the date of her wedding. ‘The people had little, but they were better off then, because there were not the differences between rich and poor that there are now.’

The Catholic mission soon became the refuge of all the sad causes in the region. Cripples, epileptics, the mentally disabled, women abandoned by their husbands, newborns with cleft palates (left to die by a society that sees any physical deformity as the sign of a grave sin in a previous life), found food and shelter here. Today it is such people who tend the garden, look after the animals, and work in the kitchens to feed the 250 orphans.

It grew late, and as we got up to leave I asked the two nuns if there was anything I could do for them.

‘Yes, say some prayers for us, so that when we die we too can go to Paradise,’ said Sister Giuseppa.

‘If you don’t get there,’ I said, ‘Paradise must be a deserted place indeed!’

This made them laugh. All the novices joined in.

As we walked to the gate Sister Giuseppa took my hand and whispered in my ear, this time in perfect Italian with a northern accent, ‘Give my greetings to the people of Cernusco, all of them.’ Then she hesitated for a moment. ‘But, Cernusco, it’s still there, isn’t it, near Milan?’

I was delighted to confirm it.

As I went down the hill I felt as if I had witnessed a sort of miracle. How encouraging it was to see people who had believed so firmly in something, and who believed still; to see these survivors of an Italy of times past, which only distance had preserved intact.

People born into a family of poor peasants at the beginning of the century, in Cernusco or anywhere else in Italy, could not dream of having the moon: their choices were extremely limited, which meant that they had a ‘destiny’. Today almost everyone has many alternatives, and can aspire to anything whatsoever – with the consequence that no one is any longer ‘predestined’ to anything. Perhaps this is why people are more and more disorientated and uncertain about the meaning of their lives.

Children in Cernusco no longer die like flies, and none of them, if asked ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ would reply, ‘A missionary in Burma.’ But does their life today have more meaning than that of the children who at one time might have answered in that way? The nuns in Kengtung had no doubts about the meaning of their lives.

And the meaning of mine? Like everyone else, I often wonder. Certainly one is not ‘born to be’ a journalist. When I was little and my relatives bombarded me with the usual stupid question, which seemingly must be inflicted on all children in all countries and perhaps in all ages, I used to annoy them by naming a different trade every time, and in the end I invented some that did not exist. It is an aspiration that I continue to nourish.

After three days in Kengtung Andrew and his friend had not yet found me a fortune-teller. Perhaps Andrew’s Protestant upbringing made him reluctant, or perhaps it was true that the two most famous fortune-tellers were out of town ‘for consultations’. Finally, on our last evening, we found one playing badminton with his children in the garden of his house. But, with great kindness, he excused himself: he received only from 9.30 to 11.30 in the morning, after meditating. I tried to persuade him to make an exception, but he was adamant. He had made a vow imposing that limit ‘to avoid falling victim to the lust for gain’. If he broke that commitment he would lose all his powers, he said. His resistance impressed me more than anything he might have told me.

On the way back to the border we saw the chained prisoners again. This time we were prepared, and managed to give them a couple of shirts, a sweater, some cigarettes and a handful of kyat.

At the border we were given back our passports, without any visa stamp. Officially we had never left Thailand, never entered Burma. A fast taxi took us to the city of Chiang Rai. We spent the night in a sparkling new, ultra-modern hotel, where young Thai waiters dressed like the court servants of old Siam served Western tourists dressed like explorers in shorts and bush jackets. The next day they would be taken in air-conditioned coaches to Tachileck, where they would be photographed under an arch that says ‘Golden Triangle’, visit a museum called ‘The House of Opium’, and buy a few Burmese trinkets of a kind that by now can be found in Europe as well.

A French mime, with a bowler hat and walking stick, who had been hired by the hotel on a six-month contract, did a Charlie Chaplin turn between the tables of the restaurant, in front of the lifts and among the customers at the bar, in an attempt to liven up the atmosphere. I could not have imagined anything more absurd, after the chained prisoners, the monks and men who chopped off heads.

The next morning Angela and Charles caught a plane, and were in Bangkok in two hours. I had ahead of me four hours by bus to Chiang Mai and then a whole night on a train. Inconvenient. Complicated. But the idea of keeping to my plan still amused me. I remembered how as a boy, on my way to school, I tried not to step on the cracks between the paving stones. If I succeeded all the way I would do well in a test or write a good essay. I have seen this done by other children in other parts of the world. Perhaps we all from time to time have a primordial, instinctive need to impose limits, to test ourselves against difficulties, and thereby to feel that we have ‘deserved’ some desired result.

Thinking about the many such bets one makes with fate in a lifetime, I reached the bus station easily enough, then the railway station, and finally Bangkok.