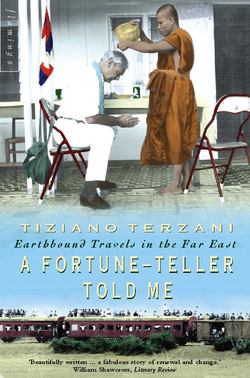

Читать книгу A Fortune-Teller Told Me: Earthbound Travels in the Far East - Tiziano Terzani - Страница 11

CHAPTER SEVEN Dreams of a Monk

ОглавлениеIs there such a thing as chance? I was coming to believe that a lot of what seems to happen ‘by chance’ is in fact our own doing: once we look at the world through different glasses we see things which previously escaped us, and which we therefore believed to be non-existent. Chance, in short, is ourselves.

At the end of February the Dalai Lama came to Bangkok on a lightning visit. During his few hours in the city he held a press conference at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club on the twenty-first floor of the Hotel Dusit Thani. Before the largest crowd of journalists ever assembled in that room, he appealed for the liberation of Aung San Suu Kyi, the imprisoned heroine of the Burmese democracy movement. He spoke of goodness, love, purity of heart and peace.

His speech left me very disappointed, and I drew no comfort from the fact that as he was leaving the room, in his kindly, smiling way he stopped when he reached me, as if my face were familiar. His hands met in front of his chest, and when I returned his greeting in like manner, he seized my wrists in a firm grasp and shook them, expressing the warmest good wishes and some sort of blessing.

‘Is he always so down-to-earth, so utterly simple? He talked like a country priest,’ I said to one of the monks who was hurrying after him. He was dressed like the others in a handsome purple robe trimmed with red and yellow, but his face was that of a Westerner, pale and short-sighted, with small spectacles. I had been watching him the whole time as he stood motionless, with a joyful smile, apparently absorbing the Dalai Lama’s words as if they were the truest and most beautiful he had ever heard.

Still smiling serenely, the monk replied, ‘Greatness may also be manifested in simplicity. This is the greatness of the Dalai Lama.’

His English was perfect, but I realized from his accent that he was not Anglo-Saxon.

‘No, no, no. I’m Italian.’

‘Italian? So am I!’

This was no chance meeting – I had been looking for this very man! He was Stefano Brunori, aged fifty, born in Florence, an ex-journalist who for the past twenty years had been a Tibetan monk with the name of Gelong Karma Chang Choub. Too many coincidences to be mere chance! He normally lived in a monastery in Katmandu, but his teachers (this word definitely caught my fancy; to have teachers must be wonderful – I haven’t had one for a long time) had allowed him to come to Thailand. He needed treatment for gastritis, caused by the ultra-strict vegetarian monastic diet. Next door to our home was an excellent hospital where he could have all the tests he needed. Thus it was that Karma Chang Choub came to stay in Turtle House.

We spent three days together, talking from morning to night. In our lives there were so many correspondences and parallels that each of us, without saying so (for it was only too obvious), could see in the other what he might have been. In that delicate play of mirrors it was easy to become friends, and perhaps to get to know each other a little.

We had both left Florence and travelled about the world, and in 1971 we both arrived in Asia. I came with Angela, two suitcases and two babies, without a job but determined to become a journalist. He too had brought a foreign wife with him, but no children, and as regards work he was already in a crisis. He was more ‘on the road’, as they used to say of those who have no clearer aim than to travel from Europe to Asia, taking pot luck when it came to transport. Usually such people would eventually disappear into some Indian ashram, or would finish up on the beaches of Goa, or in Bali, or with hepatitis in a Salvation Army hostel. In Chang Choub’s case the road had led to Nepal. In Katmandu, he said, something had happened inside him. He parted from his wife, entered a Tibetan monastery as a novice, and after some time took the vows. He was ordained a monk by the Dalai Lama himself.

From then on it was as if the burden of life had been lifted from his shoulders. He had no more possessions, the rhythm of his days was fixed by the monastic routine, all decisions were made for him by his teachers. It was they who decided if he could study another meditation method, if his mother could come and see him. A year previously, they had given him permission and money to spend the winter in a Buddhist monastery in Penang.

We soon got round to talking about my Hong Kong fortune-teller. The fact that I had decided to heed the warning and spend a year without flying did something to narrow the gap between Chang Choub’s existence and my own. Like him, I had entered an order of ideas that was anything but Florentine. I too had let myself follow the paths of Asia, and so he felt I understood him a bit better.

Of course, he said, monks with great meditative powers can see the future, but that is not their aim in meditating. They are reluctant to say what they know because they do not want to become like fairground freaks. The truly enlightened ones, like Buddha and Christ, did not like to perform miracles just to convince unbelievers. The ability was there, obviously enough, but they used it only when it was absolutely necessary.

I have always liked the story of Buddha arriving at a river and the people asking him to cross it by walking over it. He pointed to a boat and said: ‘That’s the simpler way.’

Many Tibetan monks have developed special powers. The Dalai Lama himself has a personal oracle who helps him predict the future and make decisions. It was his previous reincarnation, back in 1959 when Mao’s troops were entering Lhasa, who told the Dalai Lama exactly when to leave and in what direction to go. The flight was successful. That same oracle, it is said, is now convinced that the Chinese will soon lose control of Tibet, and that the country will regain its independence.

It amused Chang Choub to speak of his life as a monk. He gave the impression that he saw the whole story from the outside, with the irony with which a Florentine would look on a man like him, a Westerner who becomes a Tibetan monk: an anomaly, a contradiction in terms. The first years, he told me, were very hard. Weakened by the diet and the cold, he was often ill. One thing that he never got used to, and indeed found more and more unbearable as time went by, was the sound of the long horns that woke the monks at three in the morning. ‘If it had been Beethoven, Bach, you’d have got up gladly, but that booooo…booooo – on a single note that never changes, day after day, booooo…booooo – puts a strain on all my hard-won detachment from the things of the world.’ He said this almost with anger.

Even in speaking about the religious aspect of his choice, his tone was detached. ‘Buddha said we were to question everything, question the teachers and Buddha himself.’ He seemed to be justifying a deep uncertainty which, even after so many years, had stayed with him. What sounded strange to me was his way of speaking about the teachers he had studied under. Of one of them he remarked, ‘Of course, he is very advanced, he has more than two hundred years of meditation behind him.’ Of another whom he wanted to meet he said, ‘He is only nine years old, but in his last life he was one of the greatest, and this could well be his last reincarnation.’

I have lived much of my life among the Chinese, Buddhists, for the most part, who find it natural to believe that a man passes through a long series of lives, each time occupying the body of some living being; but that idea had never really engaged me personally. Talking with Chang Choub, who took reincarnation for granted, I at least understood the underlying concept of the belief. Our existence is merely a link in a long chain of many lives and many deaths. Each new birth brings, along with the body, a sum of tendencies and potentialities which result from the spiritual path followed in former lives; this is our karma. With this baggage we resume the journey where it had been left off, sometimes moving forwards, at other times backwards. The baggage of wisdom, as it were, has nothing to do with the everyday knowledge of the world which everyone must accumulate from scratch for himself. Even the reincarnation of a great guru must learn again that fire burns, that one can drown in water, and so on.

Some very advanced teachers can remember details of their previous lives with great precision. A classic anecdote tells of a child, the son of peasants, who said, ‘It’s mine, it’s mine,’ when he saw the rosary of the late Dalai Lama in the hands of a monk who was travelling Tibet dressed as a beggar in search of the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation. He found it in that child. The little boy was taken to the Potala, where he stopped outside the wall, wanting to enter at the exact spot where there had been a door during his previous life – a door that had since been walled up.

Believers also tell the story of a child who saw some Tibetan exiles in India perform an ancient ritual dance. Suddenly he cried: ‘No, no! Not that way!’ He ran among the monks and in a trance began to move like an experienced dancer. They all prostrated themselves, recognizing in him the reincarnation of a great teacher, the Karmapa. Then he became a child again, and returned to his mother’s arms.

Talking about these things with Chang Choub – I called him by that name, to emphasize my acceptance of him as he wished to be – felt like going on a long journey, while remaining seated on the veranda of Turtle House. It was like taking a holiday from normal life.

‘But surely you can’t believe in reincarnation in the strict sense,’ I said. ‘The population of the world is constantly increasing, millions more are born every minute. From whom are they all reincarnated?’ The question was banal and prosaic, a bit like asking a saint to prove the existence of God by performing a miracle. But Chang Choub did not perform miracles – far from it. He had learned countless techniques of meditation, he had been a pupil of great teachers, he had spent months as a hermit in a cave; but he admitted, with some sadness, that he had not achieved a great deal.

‘What is it you are aiming at?’ I asked. ‘What are the dreams of a monk like you?’

And for the first time I heard the word: ‘Satori.’

‘Meaning what?’

‘A moment of great clarity. The moment when you rise above everything.’

‘A moment. And you haven’t managed to get there even a moment?’

No, he said, and it was like admitting a great defeat. I was left to wonder why twenty years of effort, sacrifice, fidelity to so many vows, years of silence, cold, rice with nothing but vegetables, and the horrible sound of the horns at dawn, should have yielded such a meagre harvest. Chang Choub told me that a monk he knew had had satori one day after barely two years of exercises – suddenly, just like that, while driving along a freeway in California.

In the morning Chang Choub would sit in our salà, the small wooden pavilion over the pond, meditating with closed eyes, motionless and withdrawn. Watching him from a distance, I could not, try as I might, shake off a feeling of unhappiness which his presence conveyed to me. Between the colour of his skin and that of his robe there was a deep contradiction; I felt it too in his pose as he sat cross-legged on the floor. In him, so Western despite his Asian clothes, there seemed to be something discordant, out of kilter. I imagined that one day, surrounded by monks who are his brothers in name only, speaking a language not his own in a place where not one sound or smell was of home, Chang Choub might feel terribly lonely, lonelier than ever. I asked myself if at the end of his life he would find himself wondering – as perhaps he already does at times – whether he had not spent his days pursuing someone else’s goal, prey to an illusion that was not even his.

The crisis that Stefano Brunori had undergone twenty years previously was clear enough. It was one that sooner or later affects everyone in some way. As soon as you start asking questions you find that some of them, especially the simplest, have no obvious answers. You have to go out and look for them. But where? He chose the least expected direction, a difficult one. Perhaps he was attracted by the exotic, by the strange. Those alien words, new to his ears, appeared much more meaningful than the old familiar ones of his own language. Satori seemed to promise so much more than ‘grace’.

And yet, if that young Florentine had chosen a path furnished by his own culture and become a Franciscan or a Jesuit, if he had retired to Camaldoli or La Verna instead of a monastery in Nepal, perhaps he would have found a solution that was more familiar, more suited, less lonely. And at least he would have been spared those terrible horns in the morning! Was he, like me, a victim of exoticism? Of a need to seek the ends of the earth? After all, I could perfectly well have become a journalist in Italy, in a land which is just as exotic as Asia, a land whose real story is yet to be told.

When Chang Choub left, it felt as if we had known each other much longer than three days. He believed that at the Dalai Lama’s press conference we had simply found each other again. It cost me an effort to accept that ‘again’, but I too felt that we were joined by many, many threads which I would have liked to continue disentangling. Talking about his life had made me look again at my own; talking with him, I began for the first time to think seriously about meditation. I had seen the possible connection between the mind, trained through meditation, and powers including that of prescience. For the first time I had heard someone talk about techniques of meditation, and had been encouraged to try them out. It may be strange, but it is so. How many times had I seen advertisements for courses in Transcendental Meditation, or heard of young people going to meditate at a temple in southern Thailand? I paid no attention; it seemed to belong to another world, a world of weird, marginal people in search of salvation. I felt that it had no relevance for me personally.

Chang Choub, with the life he led, brought all this before me again, and made me think that it might have something to do with me. When he left Turtle House, with his half-empty purple sack over his shoulder, it was as if he left behind a trail of little white stones – or breadcrumbs? – to show me the way towards new explorations.

We promised to meet again in India. I have felt for years that India is in my future. In origin the reason was simple. I had grown up politically in the 1950s, when anyone interested in the Third World came up against two great myths, Gandhi and Mao – two different solutions to the same problem, opposing bets on the destinies of the two most populous nations on earth, two hypotheses of social philosophy from which it seemed that we in the West also had something to learn. Having spent years among the Chinese, trying to understand what a disaster the myth of Mao had been for them, it seemed logical to go one day to India to see what had happened to the myth of Gandhi. Living in Peking or Hong Kong, whenever we felt fed up with the prosaic pragmatism of the Chinese, or noticed ourselves reacting in a Chinese way, Angela and I would say to each other: ‘India. India.’ For us India had become the antidote to the mal jaune, that poison concocted of love and disappointment, of endless small irritations and great faith, which afflicts all those who put down roots for a while in the Middle Kingdom and then find that they cannot tear themselves away.

I would have liked to move to India in 1984, when the Chinese took a decision for me that I would never have been able to take on my own, and thus did me an enormous favour: they arrested me and expelled me from their country. But at the time I did not manage it, and more years went by. To my original reason for wanting to go to India a new and more important one has been added: I want to see if India, with its spirituality and its madness, can resist the disheartening wave of materialism which is sweeping the world. I want to see if India can solve the dilemma and preserve its uniqueness. I want to see if in India the seed of a humanity with aspirations beyond the greedy race for Western modernity is still alive.

Living in Asia, I have told myself again and again that there is no culture with the capacity to resist, to express itself with renewed creativity. Chinese culture has been moribund for at least a century, and Mao, in the effort to found a new China, murdered the little that remained of the old. With nothing left to believe in, the Chinese now dream only of becoming Americans. Students marched in Tiananmen Square behind a copy of the Statue of Liberty, and the old Marxist-Leninist rulers erase the memory of their crimes and their lust for power by letting the people run after illusions of Western wealth.

Which Asian culture has preserved its own springs of creativity? Which is still able to regenerate itself, to develop its own models, its own alternatives? The Khmer culture, which died with Angkor eight centuries ago and was once again killed by Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge in their absurd attempt to revive it? The Vietnamese culture, which can define itself solely in terms of political independence? Or the Balinese, now packaged for tourist consumption?

India, India! I said to myself, nursing the hope – or perhaps the illusion – of a last enclave of spirituality. India, where there is still plenty of madness. India, which gives hospitality to the Dalai Lama. India, where the dollar is not yet the sole measure of greatness. That is why I made plans to go to India, and meet there my fellow Florentine escapee, Chang Choub.

A rich woman from Hong Kong came to see me. She was in Bangkok to meet her guru, a Tibetan monk and follower of the Dalai Lama, ‘a very advanced teacher’. He belongs to the international jet set, at home in New York, Paris and London, and he has a following of such women, usually rich and beautiful, in constant attendance. He plays the guru and the women pay the bills, buy his air tickets, organize his life. ‘He’s the reincarnation of a great teacher. He can’t be bothered with such things,’ said the understanding lady, a consenting victim – perhaps like Chang Choub? – of Tibet’s great, subtle, historic vengeance.

Quite extraordinary, Tibet! For centuries it remained closed and inaccessible, removed from the world; for centuries, in isolation, cutting itself off from any other field of study, it practised the ‘inner science’. Then came the first explorers. At the beginning of the twentieth century the British entered Lhasa; fifty years later the Chinese occupied the country and made it a sort of colony. A hundred thousand Tibetans fled, but that diaspora lit the fuse for the time bomb of revenge.

Tibetan Buddhism, first practised exclusively in the Himalayas and Mongolia, has been spreading throughout the world. Tibetan gurus have settled everywhere, from Switzerland to California, displacing the yogis who had formerly conquered the soul of Europe in its quest for the exotic. Their dogmas, once secret, have become best-sellers. Young gurus claiming to be reincarnations of old Tibetan teachers have become the mouthpieces of this ancient wisdom. With thousands of followers all over the world, they are looked after by little circles of rich lay nuns. Bernardo Bertolucci’s advisor on his film Little Buddha was one of these young gurus, born and raised outside Tibet, but a reincarnation of a great teacher. The capital of the Dalai Lama in exile, in Dharamsala, north of Delhi, has become a place of pilgrimage for thousands of young Westerners, and he has acquired the stature of a sort of second Pope, not only a spiritual leader, but also the head of the Tibetan government in exile.

By occupying Tibet, the Chinese have indirectly sown the seeds of Tibetan Buddhism throughout the world, thus practically planting a bomb in their own house. Sympathy for the Tibetan cause is growing, and interest in the spiritual aspect has become political. The Dalai Lama is welcomed as a guest in the centres of world power. He has become the symbol of the struggle against Peking’s totalitarian regime.

The other side of the coin is that the gurus, with their mythical roots amid the Himalayan peaks and their role as representatives of an oppressed people and bearers of spirituality, provide a perfect alibi for people who pursue redemption while remaining completely enmeshed in materialism. Because of the widespread disorientation from which our culture suffers, people have lost their natural scepticism. Today any charlatan can sell his spiritual potions if he gives them an exotic name.

Am I too a victim of this phenomenon? Is that why I spend days listening to Chang Choub, why I obey the prophetic warning not to fly, and say ‘yes’ when invited to see a new fortune-teller?