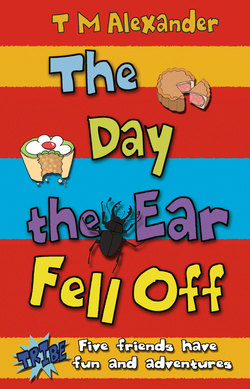

Читать книгу The Day the Ear Fell Off - T.M. Alexander - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеtea with the enemy

I didn’t say anything. I couldn’t. There was a tight feeling as though someone had bandaged up my lungs a bit too tight with parcel tape.

Loads of questions were flying around my head, out of my ears, back in through my nose, buzzing in front of my eyes.

Will Jonno rat on us?

If he does, what will Mum say?

If he doesn’t, will we all pretend to get on like proper mates?

Will Jonno go along with it?

Will I be able to swallow my tea with Jonno staring at me?

Does Jonno have any telltale signs of being throttled?

The words started to reorganise themselves into nonsense:

I like to swallow throttled rat.

Mum drew level and gave me a worried look. ‘I know you don’t like things that aren’t planned, but Jonno’s mum was so pleased that I asked, and when she suggested today . . .’

I could feel my legs start to tingle. Luckily Mum knows the signs.

‘Take a breath NOW,’ she ordered.

I did.

‘That’s right. And another.’

HOW I BECAME A BREATH-HOLDER

When I was a tiny baby and couldn’t walk or talk or get food in my mouth without smearing it over my face first, my mum had a bright idea: I think I’ll take this little baby (who can’t even sit up) for a swim. So she took me and my sister Amy (who was five) to the pool and (because she’d been told that babies can swim underwater) she let go of me. I floated below the water for a bit while she chatted to Amy and then (when she remembered I was there) she pulled me out of the water.

At that point, I was meant to take a big breath but no one had taught me that, so I didn’t. That was the first time I went blue.

Amy says that after that I did it every time I didn’t get my own way. But that’s a lie.

Everything started to come back into focus. I’ve been a breath-holder since before I could talk, although it doesn’t happen very often now. I don’t mean to do it. It just happens. I forget to breathe, go bluish and then faint. Luckily as soon as I begin to faint my body takes over and I start breathing again. Fifty’s mum says it’s attention-seeking behaviour. My mum says it’s a quiet version of a tantrum and tells everyone to ignore me. That’s what it’s like having a mum-doctor! Even if I’m really ill, all I get given is a spoon of pink medicine and a vest.

The breathing helped. I needed to stay calm.

‘The car’s just along here. Jonno, would you like to sit in the front with me so we can get to know each other?’

‘Thank you,’ said Jonno. I hadn’t noticed his voice before. It was proper, like on the radio.

Flo scrambled on to her seat and I got in the middle, followed by Fifty. Using faces and signs, we panicked silently. Mum did the talking. ‘Your mum’s description was spot on, Jonno. I had no trouble finding you.’ She paused. ‘So how are you settling in?’

‘OK so far,’ he said. Phew!

‘Snack?’ Mum asked as we walked into the house.

‘Yes, please,’ said Fifty and Jonno at the same time.

‘Yes, please, Mummy,’ said Flo. She’s a creep.

The four of us sat at the kitchen table eating cheese biscuits and drinking blackcurrant. Luckily Flo chats to anyone so she made all the noise. I was completely mute. What could I say to a boy we’d deliberately told on for things he hadn’t done, been rude to and practically beaten up?

‘What are you going to do before tea?’ Mum said.

Fifty could see I still wasn’t functioning so he stepped in. ‘I think we’ll go outside and . . . find something to do there.’

‘Good. What about you, Flo?’

‘Can I do Play-Doh?’

‘Of course,’ Mum said. She cleared away the plates and sent us out.

So we stood on the grass.

My gaze was fixed on the wavy blades, the bright shiny green and the duller greyish green of the underside. I could easily have stopped breathing again. It would have been better than the embarrassment of not knowing what to say. And the worry that we’d still be standing in a silent circle when Mum called us for tea. And if she never called us for tea because a big wave swept her away, then we’d grow old and grey and die there. In between my desperate thoughts, a label kept gliding into view, like a subtitle on a film. It said, SORRY.

‘Sorry,’ said Fifty.

My head snapped up. ‘Yes. Sorry.’

‘Accepted,’ said Jonno. ‘I’ve had worse welcomes.’

Although we’d only said eight words between us, everything changed. Not speaking was so uncomfortable. Speaking was like finally having a pee when you’ve been holding on and holding on. Jonno grinned so I grinned back.

‘Have you been to lots of schools?’ asked Fifty.

‘Enough. This is the fourth school in seven years.’

‘Did you get expelled?’ Fifty said.

‘No, but I wouldn’t have minded if I had. I’ve been to schools where the classroom is scarier than being in a cage with . . .’ He paused.

‘A panther?’ I suggested.

‘I was actually deciding between the devil and the tooth fairy, but a panther would do. Did you know there’s no such species?’

‘There is. It’s black and it’s a cat,’ said Fifty.

‘It’s black and it’s a cat, but it’s actually a leopard or a jaguar with black skin. Opposite of an albino.’

‘I didn’t know that,’ I said.

‘Same,’ said Fifty.

After that the questions flew: Why does he keep moving? When is he moving again? Why is he scared of the tooth fairy? (He isn’t, any more.) Which school was the best? What is the worst thing that’s happened to him? How far can he see without his glasses? (As far as his elbow. )

We started to chuck a ball around as we chatted and it was OK. (And his neck looked normal!) He’d lived in London and Glasgow, where he met his best friend, Ravi. His worst first day was in Oxford where the teacher asked a posh kid to show him the way to the loos and he showed him the girls’ not the boys’ and then went and got all the other boys so they could watch him come out. How nasty is that?

It was nice talking to someone new – we all know everything there is to know about each other.

Jonno asked questions too: Why do you have such strange nicknames? I can guess Keener, but Fifty? Copper Pie?

We enjoyed answering that.

NICKNAMES

COPPER PIE: Ages and ages ago (we must have been about six) he was eating in class (absolutely not allowed) and the fill-in teacher (a man who didn’t know any of our names) shouted, ‘You with the ginger hair, put down that sandwich.’ And C.P. yelled back, ‘My mum says it’s copper, not ginger, and this is not a sandwich it’s a pork pie.’ He’s been Copper Pie ever since.

FIFTY PER CENT (or FIFTY): He hasn’t grown since he was about three, so he’s half the size of everyone else.

BEE: Short for Beatrice.

KEENER: It’s obvious, isn’t it?

JONNO: Has never had a nickname.

‘Do you want to go out the front?’ I said. Our garden’s quite small so we often play on the road.

We decided to play piggy in the middle, one on each side of the road and the pig in the middle, who had to try to get the ball and not get run down. I was in the middle, and had been for ages, when we heard yelling.

‘Keener!’ It was Copper Pie, and someone chasing him – Bee.

What were they doing here? My house isn’t on the way to Bee’s or C.P.’s. She lives on the estate and he lives on the main road.

Copper Pie skidded to a stop two drives down. So I ran over.

‘What is it?’

‘What’s he doing here?’ Copper Pie gave Jonno the evil eye.

‘Long story. Mum invited him. He’s all right.’

‘He’s the reason I’m for it.’

‘Come on, Copper Pie. He just wanted someone to hang out with. Do you know he’s never been at a school longer than about five minutes? He’s always been the new boy.’

‘So?’

‘Anyway, why are you here?’

Bee caught up. ‘Trouble. Big, big trouble.’

Fifty came over. ‘Did I hear trouble is brewing, witchy-poo?’

‘Brewed,’ said Bee.

Copper Pie sat on the kerb and put his head in his hands.

Bee made an aren’t-you-going-to-tell-them face, but he didn’t look up.

‘What is it?’ I said. ‘Did something happen on the way home?’

Bee shook her head.

‘Well there wasn’t time to get in any more trouble at school today,’ I said. ‘Was there?’