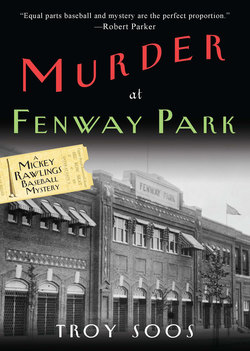

Читать книгу Murder at Fenway Park: - Troy Soos - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Seven

I showed up two hours early for practice Monday morning. Except for that interrupted view through the runway corridor, it was my first real look at the Fenway Park playing field.

It was the damnedest baseball field I had ever seen. There was a hill in left field! About twenty-five feet in front of the left field fence, the ground began an upward slope, rising to a height of ten feet where it made contact with the wall. The rest of the park was strange, too. It seemed as if it had been squeezed in several directions to fit into the shape of the building lot. The outfield fence went from shallow to deep to shallow as it wound its way from the left field corner around to right, with a number of interesting nooks and corners that would make playing the outfield far too much of an adventure for me.

I was surprised that my roomie also arrived early to get in some extra fielding practice. As my counterpart in the outfield, Clyde Fletcher filled in for Speaker, Hooper, or Lewis if they needed relief. He hadn’t played so much as a single inning this year, but here he was, eager to shag some flies. I had dismissed him before as a dissipated sloth, but he obviously took professional pride in his play, and I grudgingly discovered that I was developing some respect for him.

Since there were no other players around, Fletcher and I traded off. He hit me practice grounders, then I hit fungoes out to him in left field. He looked pretty comical stumbling up the hill trying to go back for fly balls, but I had to admire his determination. He said if he never got into a game all year, he was going to conquer that hill. I suggested that if he got rid of his enormous wad of tobacco, he’d be a lot lighter and could run up the slope faster. He suggested I do something to myself that I unfortunately had never yet experienced doing to anyone else. I decided Clyde Fletcher and I might get along after all.

Soon other players joined us on the field, and fans trickled into the stands. I picked out the Red Sox stars as they warmed up—the ones who played with ease and grace, the natural ball players Clyde Fletcher and Mickey Rawlings would never be. We could fill in for the stars when they were hurt, but we’d never have their fame and stature.

Centerfielder Tris Speaker was the team’s leader and second only to Ty Cobb as the best all-around player in the American League; he was exchanging long throws with Duffy Lewis and Harry Hooper in the outfield. Jake Stahl, coming to the end of the line as a player but still batting .300, was hitting pepper to the infielders. Baby-faced fireballer Smoky Joe Wood threw light pitches to Bill Carrigan along the right field foul line. Next to him, throwing more seriously, was today’s starting pitcher, Bucky O’Brien.

This team could win it all. Jimmy Macullar could be right: the Red Sox could be on the way to the World Series. If the current roster survived the season. A fan, an opposing player ... could a Red Sox player be next? Would the first year of this magnificent, peculiar ballpark be ruined by more tragedies? I wanted to yell out to the players who were warming up so leisurely. To scream a warning at them. And, just as strongly, I wanted to keep utterly quiet—to forget all I knew and all I feared.

I didn’t yell. But I knew I wouldn’t keep my thoughts to myself much longer.

When the ball game against the visiting New York Highlanders got underway, Clyde Fletcher and I were both relegated to the pines. As the Red Sox regulars took the field, the two of us sat together at one end of the nearly deserted dugout. Hal Chase led off for the Highlanders, and I remembered our last game in New York. I nudged Fletcher with my elbow and asked him, “Hey, Fletch, do you believe the stories about Chase?”

“What stories?”

“That he throws ball games.”

Fletcher looked down the length of the bench, and seemed satisfied that we were out of earshot. Veterans don’t like to be seen talking to rookies. Hchoowook. Shptoo. Schplat. “Well, I don’t know that he throws games, but I’m sure of it.”

“What do you mean?”

“I don’t think nobody ever caught him at it, and I never heard him admit it, so I can’t say that I know it. But from what I do know about the son of a bitch, and what I hear from other guys who know him, I’m sure of it.”

I suppressed an impulse to tell Fletcher that I had caught Chase blowing plays. “Why does he do it? Money?”

“I dunno... maybe money. Mostly I think it’s a game with him. He likes the idea of pulling something over on somebody.” Fletcher grimaced. “It’s not just ball games, either. He took me in a card game once.”

“Cheated?”

“Oh yeah. I didn’t realize it till after the game, but no doubt about it. I watch for that in poker, but this was a goddam bridge game. Me, Addie Joss, Billy Neal, and Hal Chase. Chase took all of us, got away with a bundle. He seemed too sure of himself during the game, grinning like it was some kind of joke. His goddam joke cost me two months’ salary. But—nothing I could do about it.”

“Jeez.”

Hchoowook. Shptoo. Schplat. “Yeah.”

One thing about his story surprised me. Joss had been one of the best pitchers in baseball until he got sick and died the year before. I couldn’t imagine Fletcher palling around with a star player. “You knew Addie Joss?” I said.

“Not real good, but yeah, I knew him. I was with him in Cleveland.”

“He could have been a great pitcher.”

“He was a great pitcher. He just died too young. Barely thirty years old.”

I suddenly wondered how old I’d get to be.

With the Highlanders side retired and the Sox fielders coming into the dugout, our talk ended.

Fletcher and I remained on the bench throughout the game, and thus avoided contributing to our 3—1 loss. The fans were vocally disappointed, not only at losing, but for hometown favorite Bucky O’Brien who was charged with the defeat.

After the game, O’Brien stopped by his aunt’s rooming house for dinner. I welcomed what I thought was an opportunity to get to know him better, but he was in a surly mood after the loss to New York and didn’t say much at first.

His aunt, a short, round, chatty woman who seemed to think of herself as a mother to her boarders, explained that her stuffed cabbage was the only thing that could console Bucky after a loss. Whenever he was pitching in Boston, she would prepare it for supper. If he won, he’d go out to celebrate with the other players, leaving plenty of extra food for her boarders; if he lost, he would visit her and gorge himself with cabbage.

After filling himself this evening, Bucky revived a bit and became more talkative. The two of us went into the parlor after dinner, and after settling ourselves in overstuffed chairs, he started to review every pitching mistake he made in the game. I liked the fact that he only criticized his own performance; he didn’t complain about scoring opportunities missed by the Red Sox hitters, or lack of hustle by the fielders, or poor pitch selection by Bill Carrigan behind the plate.

Bucky had arrived in the big leagues late. His aunt told me that his thirtieth birthday was day after tomorrow, and I knew he was in only his second major-league season. He seemed determined to do everything in his power to stay in the majors for whatever good years he might have left. Too many seasons in the minors—grueting travel, cheap hotels, bad food, worse companions—had taken a toll on him. Bucky’s short brown hair was neatly groomed and a stylish blue suit draped his muscular frame, but he had sunken eyes and an overall grizzled look that would be his forever.

After he had gotten the self-criticisms out of his system and relaxed a little, I decided to broach the subject of the dead Tiger player. “Say, Bucky, I heard one of the Detroit players got killed during the last series here.”

“Yeah, Red Corriden. I struck him out three times in the last game. Couldn’t touch my spitter.” Bucky was still thinking like a pitcher.

I tried to move off of Corriden’s batting ability. “Clyde Fletcher was telling me he thought Corriden used to play with the Browns.”

“Sure did. Don’t you remember what he did in the batting race a couple years ago?”

“The batting race?”

“Yeah. Where you been? The Browns tried to give the title to Nap Lajoie. Remember?”

“Ohhh, okay. I thought his name sounded familiar. That’s where I heard of him.”

“Yeah, it’s a damn shame. Now the kid’s just going to be remembered for being a sap.”

“I read about what happened, but it seemed awful mixed up. I still don’t think I know what all went on. It was over a car, wasn’t it?”

“Not just a car, it was a Chalmers 30. I don’t make enough in two years to buy an automobile like that. I don’t know if it was really about the car though, or because Ty Cobb’s such a mean son of a bitch that everybody hates him.”

“I remember Cobb and Lajoie went just about all of 1910 neck and neck for the batting title—and whoever won the title would get the car as a prize. Right?”

“Yup. Then it came down to the last day of the season. Cobb was ahead by a few points, so he didn’t play—didn’t want to risk going hitless and blowing his lead. Son of a bitch is as gutless as he is mean. Anyway, the Tigers let him sit out.