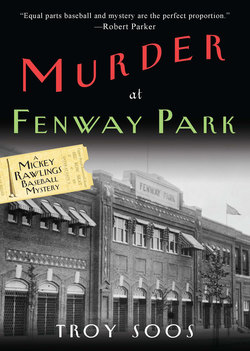

Читать книгу Murder at Fenway Park: - Troy Soos - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Four

My new teammates milled about home plate, coordinating their moves so that each time I tried to step to the batter’s box I was blocked out. This came as no surprise; preventing rookies from taking a turn at batting practice is a standard part of the hazing ritual new ball players have to endure. For form’s sake, I maintained a pretense of expecting a chance to hit, but I really didn’t mind when other players elbowed in front of me and stepped to the plate. I was engrossed in scanning the Hilltop Park stands. This was the first time I’d been in a stadium as a player where I used to come as a spectator.

The grandstand behind third base was filling up with fans: office clerks taking an afternoon off to attend a nonexistent aunt’s funeral, and courting couples who sat high in the stands to enjoy the view of the Jersey Palisades across the Hudson River.

Outside the right field foul line lay the open bleacher seats, bare pine boards occupied mostly by kids who couldn’t afford better vantage points. Less than ten years ago, I was one of those eager faces dreaming of actually being on this field some day.

Box seats between home plate and the dugouts held middle-aged men in business suits and derbies who looked as if they could afford the best. I had never been able to get a ticket for one of those seats, and gloated that today I would be sitting in an even better location: the dugout bench.

Everywhere, the ballpark was alive with sounds that had been dormant all winter and now burst out with the coming of April. From a hundred directions came the sociable buzz of friendly arguments—about off-season trades, which teams would make it to the World Series, which players were over the hill and which were promising rookies. Over the chatter, vendors barked Peanuts! and Beer! and fans shouted their orders for same. From the field came the sharpest sounds: loud cracks of wood on leather as hitters teed off on soft tosses from the batting practice pitcher; and hard pops of leather on leather, as baseballs were thrown into mitts eager to snap them up.

Ten minutes to game time, Jake Stahl called us in to the dugout. Contrary to what Bob Tyler predicted, Stahl had decided not to start me. He said he’d let me get adjusted to the team before putting me in the lineup. I wondered if he was also letting me recover from the episode in Fenway Park, but he said nothing about it.

I sat by myself at the end of the dugout bench. I knew the first rule for rookies: they should be seen and not heard. I also knew the second rule: they shouldn’t be seen either. To my teammates I had as little stature as a batboy. It would take a while for me to be accepted by them. Usually the way it worked was that a rookie would be paired with a veteran player on road trips. After the veteran showed the youngster around and gave his approval, the other players would start to think of him as part of the team, too. My roommate was to be Clyde Fletcher, another utility player, but only his luggage made it to our hotel room last night so we had yet to meet.

The game got under way with Harry Hooper leading off for us against Hippo Vaughn. The Highlander pitcher looked as huge as his name implied, but I thought he was more imposing in appearance than he was in performance (of course it’s always easy to think that from a safe spot in the dugout or the bleachers). Hooper had no trouble with him, lining a single back through the box on the second pitch.

While the next batters took their turns, I fixed my attention on Hal Chase at first base. I was oddly comforted by his presence there. Not because it was Chase—famed equally for his fielding prowess and his unsavory character—but because he was a player I had watched as a boy in this very ballpark. When I was a kid, sitting in the bleachers and fantasizing about playing in the big leagues, I always envisioned in my daydreams playing against the very players who were on the field in the very ballparks where I watched them. Those players had been leaving the game, though, and huge new stadiums were replacing the homey ones I used to know. So it was with a feeling of comfortable familiarity that I sat in old Hilltop Park, reassured to see Hal Chase manning first base for the Highlanders.

Six and a half innings went by with the Sox hitters methodically driving singles and doubles off of Vaughn and circling the bases for seven runs. Our pitcher, Bucky O’Brien, just as methodically mowed down the New York batters, holding them scoreless with only two hits. Already some fans were crossing the corner of the outfield to get to the exit gate in the right field fence. It seemed odd to see people walking through fair territory while a game was in progress, but it was one of the quaint facts of life at Hilltop Park.

“Rawlings! You come here to sleep or play ball?”

I looked up at the angry voice. “Huh?”

Stahl was standing in front of me, clutching his mitt in one hand and pointing toward the infield with the other. “I said you’re playing second. Get out there! We’re not paying you to sit on your ass.”

I snatched my glove and stumbled out of the dugout, running to second base. Jake followed close on my heels to take his position at first. O’Brien threw his last warm-up pitch, and the Highlander leadoff man stepped into the batter’s box. I was now officially in my first Red Sox game. Stahl must have figured that with a 7–0 score it was safe to put me in.

I was a tight bundle of nerves anyway. To settle down, I went over the fundamentals: if it’s a grounder to me, I throw to Stahl at first ... a bunt toward first, I cover the bag ... a hit to right field, I move out for the cutoff throw ... a drive to left, I cover second.

None of these situations developed, as O’Brien struck out the first two batters and the third flied out to center. I jauntily trotted off the field, having accomplished nothing but feeling satisfied at having done nothing wrong.

I didn’t get a turn at bat in the top of the eighth, as our side went down in order. In the bottom half, my first fielding chance came as Hal Chase himself hit an easy one-hopper to me. I played it cleanly, and felt my confidence grow.

I was due up fourth in the final frame, so I wasn’t sure if I’d get to bat at all. Tris Speaker then led off the inning with his second double of the game and my chances improved. Speaker moved to third base on a fielder’s choice, and I moved to the on-deck circle. I swung two bats together to loosen up. They weren’t my usual bats, but new ones that I bought in a sporting goods store earlier in the day. The short stubby pieces of wood had roughly the same heft as the homemade bats I’d left in my hotel room.

Stahl struck out looking, and I approached the batter’s box slowly. As nervous as I first was in the field, I was more so coming to the plate. At second base there was always a chance that I wouldn’t be involved in a play, but in the batter’s box there was no place to hide. It would be just Hippo and me.

I took my place in the box, kicking my right spike into the dirt. When facing a pitcher he hasn’t seen before, a hitter will usually take the first pitch looking. But I didn’t like to let good ones go by, so I would choose one spot and one type of pitch, and if it was served there, I’d take a rip at it. I now tried to pick a location for the first pitch, but absolutely nothing came to mind. While I frantically tried to think of the pitch I wanted to look for, I unconsciously kept kicking with my shoe.

“Hey, busher! Dig it a little deeper! You’re gonna git buried in it!” Hippo got my full attention with that yell. I called time and backed out of the box. Glancing sideways at him, I could see that Hippo did not look happy—no surprise since he’d taken a beating from the Red Sox hitters. Okay, so I have to expect one at my head. No pitcher likes to have a batter dig in on him, and none would let a rookie get away with it. Just what I need: something more to think about. Okay, if it’s a fastball knee-high down the middle, I’m swinging. If it’s at my head I’m ducking. But Speaker’s on third; if Vaughn throws a wild pitch, he’ll score, so maybe he won’t try throwing at me. But if he hits me, the ball’s dead and Speaker can’t advance, so he will throw at me, but he’ll make sure not to miss me. Hmmm ... Only one thing is for certain: it is impossible to think and hit at the same time.

I took my stance in the box. In less than a second, I gracelessly dropped to the ground as Hippo tried to keep his word. He was mad—the ball was thrown behind my head. That’s where you throw it if you really want to hurt somebody; the batter’s instinct is to duck back into the path of the ball. But the ball missed me, and the catcher missed the ball, so Speaker trotted home with another run. Vaughn apparently didn’t care if he lost 7–0 or 8–0.

Okay, this isn’t working out badly. We have another run, and my pants are still dry. Considering the scare I got, I should get an RBI for that run.

The next pitch from Hippo was right where I wanted it. I pulled the trigger, but a little too early. The ball cued off the end of the bat and rolled up the dirt path from home plate to the pitcher’s mound. Vaughn threw me out before I was halfway to first base. A pretty good at bat: I got some wood on the ball, and earned that moral RBI for Speaker scoring.

The clubhouse was boisterous after the easy victory over New York. The players kidded each other, snapped a few towels—and sawed my new bats in half while I was in the shower.

When I discovered the useless pieces of lumber they left me, I loudly let loose with most of the cuss words I knew—a considerable repertoire after all my years around ball players. My teammates laughed at my reaction to their little prank. Welcome to the Red Sox, kid. What they didn’t know was that I was really relieved. One more aspect of the hazing was over, and I could safely bring in my good bats.

A stocky player with a small towel around his waist and an enormous wad of tobacco in his cheek shuffled up to me. Lush patches of wiry black hair sprouted on parts of his body where I didn’t even know hair could grow. “I’m Clyde Fletcher,” he said, spraying a shower of tobacco juice in saying the “tch” of his last name. “We’re gonna be roomies. I got plans for tonight, so if Jake comes by for bed check, tell him I went out for cigars. Got it?”

“Yeah, sure.”

“Goo’ boy.” Fletcher belched out a dribble of brown juice, turned around to reveal a broad back that was nearly as hairy as his belly, and returned to his locker.

I remembered reading once that Rube Waddell had a clause put into the contract of his roommate that prohibited him from eating crackers in bed—Waddell said the noise kept him awake nights. I had a feeling I would soon be wishing for a roommate whose most annoying habit was munching crackers.

I was back at the Union Hotel by half past six. I walked up three flights of stairs to my room, intending to lie down for an hour and then go out for a late supper. But my bed was already occupied.

Neatly laid on top of the cover was Mabel, my favorite bat. She was lengthwise, with the knob toward the foot of the bed and the barrel denting the pillow—right where my head would be.

I turned to look on either side of the door. No one there.

Who put the bat on my bed? And how did he get in? I quickly examined the door lock: it was intact, no sign of force. And I’d needed the key to open it. I swept across the room to the one window—it was unbroken, securely locked, and sealed up with thick beige paint.

I checked the rest of the room. The two sagging iron-rail beds were still made up. Fletcher’s bags were at the foot of his, the same as they were last night. A pitcher of water and my shaving tools were in place on the washstand. I sifted through my luggage and the dresser drawer where I’d stashed my clothes; nothing was taken or moved. Everything looked in order.

Staring at Mabel, I sat down on the room’s only other piece of furniture, a pinching straight-back chair with legs of unequal length.

This was no prank by playful teammates. Nor was it an attempt at burglary or vandalism. This was a message. The context of the message was obvious: it had to do with the man I’d found at Fenway Park. But what was the content—what exactly was I being told?

Was it a warning, telling me to keep quiet about my find or I’d end up the same way? Or was it a notice, the calling card of some perverse killer? Had the dead man at Fenway also found a bat in his bed? I read all sorts of ominous scenarios into the sight of one round piece of wood.

I’d made Mabel when I worked in a furniture factory. Instead of the usual ash, I selected a choice block of hickory, turned it down on a lathe, and sanded it smooth. As the bat took shape, I named it for movie star Mabel Normand, and “it” became a “her.” I spent long hours honing her with a hambone to keep her from chipping, and rubbing sweet oil into her to protect the wood. Now, as I worried over the message she bore, I couldn’t even bring myself to touch her. What I had so lovingly created repelled me.

Not until Jake Stahl knocked and announced himself at the door could I move her; I grabbed her delicately at each end and stashed her under the bed.

When I let him in, Stahl took a glance around the room, and wearily asked, “Fletcher out getting cigars?” I nodded, but doubted if I seemed convincing.

“Uh-huh,” he grunted. Stahl wore a tired expression and a blue herringbone suit that looked a size too small. “Don’t worry about it, kid. You did okay today. Tomorrow you’re starting at second. When we get to Philadelphia, you’ll fill in at shortstop. Get some sleep.”

He turned to go out the door, and added, “Oh ... don’t bother to wait up for Fletcher.” When Stahl left, I thought his was a job I didn’t envy. He was expected to bat .300, field his position at first base, run the team in the day, and baby-sit it at night.

With my bed now free, I undressed and tried to take Stahl’s advice.

Once I was under the covers, it occurred to me that whoever left the message might return, perhaps to clarify its meaning. I tried to sleep lightly, keeping one eye open to spot any intruder. I found that it can’t be done. All I accomplished was tire my eyes by trying to close only one at a time. I was soon asleep.

I awoke with a ringing in my ears. Was that the alarm clock? No, it’s still dark out. Wait a minute, are my eyes open? I chafed my right eyeball by sticking a fingertip in it. Yes, my eyelids are open. So, it’s still night. Why am I awake?

Hchoowook. Shptoo. Ping!

That was the noise. I sat up.

“You up, kid?”

“Mmm ... yeah.”

Hchoowook. Shptoo. Ping! Fletcher hit the spittoon with another gob of tobacco juice. “Well, you oughta go to sleep,” he said. “We got a game tomorrow.” With that helpful advice, Fletcher spit out his wad and plopped into bed.

The next day, I did get a turn at batting practice, probably because nobody else wanted one. It was a chilly sunless spring afternoon and there were bees in the bats. Unless the ball was hit with the sweet part of the bat, it stung like hell to make contact.

Since I was starting the game this time, I paid attention to the field instead of the bleachers and the fans. And to get my mind off the message that was left in my room, I tried to concentrate on the proper use of a baseball bat. After taking my practice hits, I checked out the ground near home plate. I wanted to see how far a bunt would travel, and in what direction. Some groundskeepers graded the foul lines so that balls would tend to roll either fair or foul, depending on their own team’s bunting skills. The ground here looked level, but it was packed hard. To keep the ball from skipping too fast and far, I’d have to deaden a bunt by holding the bat loosely.

I headed back to the dugout where most of the Sox sat huddled in their red plaid warm-up jackets. Without a jacket of my own, it struck me how drab the Red Sox uniform was in comparison with the bright coats. The entire outfit was flat gray with faint blue pinstripes, even the bill of the cap; the only extra decoration anywhere was BOSTON spelled out on the front of the jersey in navy block letters. The Red Sox’s new ownership may have done a great job building Fenway Park, but Bob Tyler and his partners would have done well to snazz up the team uniforms some, too.

Only two other players lacked the colorful overcoats: pitcher Charlie Strickler and catcher Billy Neal, an aging battery that just joined the team. Continuing his effort to bolster the injured Red Sox roster, Tyler bought the duo from Frank Navin for $5,000 cash. It gave me some degree, if only a day’s worth, of seniority on the team.

Holding the lineup cards in one hand and a battered brown megaphone in the other, the plate umpire faced the crowd behind home plate and announced the starting lineups. He must have given the names of both nines, but all that caught my ear was Rawlings, Second Base. I savored the sound as it echoed through the stadium.

The Highlanders were throwing Jack Warhop at us. Smoky Joe Wood, the only Sox player who looked as young as I, was pitching against him.

Harry Hooper again led off the game, this time by popping out to third. Duffy Lewis and Tris Speaker went down easily, too, and I trotted to second base as the Sox took the field.

I quickly discovered why Joe Wood was called “Smoky”: he threw the ball so fast that the only thing visible was the smoke that seemed to trail behind it. I used to think this an exaggeration by the sportswriters, but the blur of the speeding ball really made it look like it had a tail of steam. Smoky Joe had his best stuff this day; he shut down the Highlander batters in the first inning, striking out the side.

The game was still scoreless when I led off the top of the third. I chose my spot for the first pitch: curveball, belt-high on the outside corner. That’s where Warhop put it, and I took a cut. The ball broke sharper than I expected, and I topped it a bit, hitting a hard grounder between third and short. I tried to leg it out to first, as the shortstop went in the hole to field the ball. I should have been out by a step or two, but the play didn’t click somehow. As usual, Hal Chase had been playing a deep first base, and he didn’t get to the bag in time for the throw. The ball skipped off Chase’s glove and flew into the stands. I went on to second base as the umpire retrieved the ball from the fan who caught the overthrow.

That play felt funny. The timing was off, and it shouldn’t have been. I looked to first base, and saw Chase smirking as he moved back into position. Was he playing his games again? Although Chase was unquestionably the best fielding first baseman in the game, he was known for slacking off at times. Rumors had it that he was friendly with gamblers and would sometimes throw games for his pals. But I don’t think anyone ever actually caught him at it. Perhaps the stories circulated only because there are always rumors about odd people—and Chase was certainly that. Who but a screwball would throw lefty and bat righty?

While I speculated about Chase, Warhop picked me off second. It is impossible to think and run at the same time.

The innings passed quickly with neither team scoring.

Whenever the Sox batted, I kept my eyes on Hal Chase, looking for any funny business. If he was trying to throw the game, he’d have to blow some more plays.

In the fourth, Duffy Lewis grounded to third and again Chase didn’t make it to the bag in time. He did look to be hustling, but again the rhythm of the play was wrong.

My next at bat came in the sixth. With a 2–2 count, Warhop served up a low lazy curve. I slid my right hand up the barrel of the bat and rapped down at the ball with a short stroke. The ball shot off the wood, down onto the hard earth. It hit a foot in front of home plate and bounced up to the height of a pop fly. By the time it came down, I had crossed first base safely. Hal Chase glared at me with pale gray eyes and greeted me with scorn, “Nobody hits Baltimore chops no more.” That’s okay—so what if I’m old-fashioned? I’m on first base with a single. But there I stayed, as the hitters who followed me went down on outs.

The game remained scoreless into the top of the ninth inning. And that’s when I figured out how Hal Chase did it.

Jake Stahl hit a grounder to third to open our half of the inning, and I kept my eyes on Chase from the moment the bat made contact. While the ball skipped to the third baseman, Chase stayed anchored well off the first base bag. Then just before the ball was fielded, he broke for the base. When the third baseman’s throw arrived, Chase was hustling as hard as he could to take the throw at first—but his initial delay ensured that he wouldn’t be in time to catch the ball cleanly. The son of a bitch. He was really throwing the game.

Yesterday, with the sight of a dead man still fresh in my eyes, I would have thought that murder was the most heinous of crimes. But now I’d seen Hal Chase try to throw a baseball game. It was an offense that seemed worse than murder—a crime less gruesome, but a sacrilege more sinister.