Читать книгу Murder at Fenway Park: - Troy Soos - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Three

The whitecaps of Mystic Seaport sparkled through the window to my left; less than twenty-four hours ago, I’d admired them through a window to the right. Since Boston and New York both prohibited Sunday baseball, today was used for travel, with the entire Red Sox team on the train heading to Grand Central Station.

Tyler’s generosity in putting me up at Boston’s newest hotel had been wasted. Last night was a sleepless one—every time I closed my eyes, I was jolted awake by the full-color image of a viciously battered face. Exhausted from yesterday’s catastrophes and drowsy from lack of sleep, I dozed off after boarding the train and napped until the sunlight skimming off the water penetrated my eyelids.

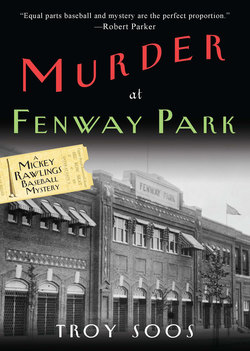

Before leaving the hotel this morning, I had stopped at the newsstand for a paper. The lobby had been surprisingly tranquil—I’d expected to encounter newsboys shrieking lurid headlines, “Murder at Fenway Park! Red Sox Rookie Stumbles on Stiff! Read all about it!”

I now scanned Page One of the Boston American and saw that the crime didn’t make the front-page news. Most of the articles were still about the Titanic, although it had been two weeks since it sank. The death toll was up to fifteen hundred, but I was unaffected by the enormity of that tragedy. I was concerned with just one death, one victim who had lain shattered before my own eyes.

I turned the pages, puzzled to find no mention of the crime. Eventually, a small item headed GRISLY DISCOVERY caught my eye. But the story turned out to be about a robbery victim who had been found beaten to death in Dorchester. There was nothing about the body at Fenway Park.

I felt a need to know something about the man I’d found. I wasn’t looking for a particular piece of information, just something that would humanize him: his name, where he lived, his work. Anything would do. If I could associate him with some other aspect of his identity, then maybe when he entered my thoughts—and I was sure he would on many nights to come—I could envision him in some way other than as that shockingly mutilated face.

Until I could picture him differently, I would just have to try to avoid thinking about him at all.

With some effort, I gradually prodded my thoughts away from the dead man.

And there were indeed more agreeable musings available to occupy me. For despite the disturbing start to my association with the Red Sox, I had every reason to look forward to what was ahead. Particularly to our immediate destinations: my first appearances in New York and Philadelphia as a major-league baseball player.

I grew up in Raritan, New Jersey. It was perfect for seeing major-league baseball, even though the state itself didn’t have a single team. In a journey of less than two hours I could reach the home grounds of any one of five big league clubs: the Giants in upper Manhattan, the Highlanders—or Yankees as some papers called them—in the Bronx, the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the Phillies and Athletics in Philadelphia.

I was raised by my aunt and uncle. Uncle Matt ran a general store in town and taught me baseball. And he gave those tasks about equal priority. My earliest memories are of playing catch with him in the backyard.

My uncle took me to major-league games whenever he could, usually to the Athletics’ Columbia Park, where I could cheer for my favorite player: Rube Waddell, a hard-throwing eccentric pitcher who spent his off-time wrestling alligators and chasing fire engines.

As I was growing up, I worked hard to polish the baseball skills I had and learn the ones I didn’t have. I rarely attended school, finding it useful only for rounding up enough other boys to play a full-scale ball game. I tried to get into every baseball game that the boys would organize, though I dreaded the choosing-up-sides ritual. Not once was I the first boy picked. I was smaller than most of the other kids, and despite all my practice, there was always one boy who could throw harder than I could, another who could run faster, and many more who could hit the ball farther. But I was usually the best fielder and best place hitter, so I was never the last picked either.

When I was fourteen, my aunt died after a brief illness. Uncle Matt didn’t feel like playing catch or doing anything else anymore. With my aunt gone, my uncle totally withdrawn, and school holding no interest for me, I was on my own.

I always knew that my career would be in baseball. I also knew that I would never be a star. But I figured I could have a pretty good career as a journeyman ball player and then go on to coaching and maybe managing.

The first teams that paid me to play were factory teams. Many companies would give jobs to men or boys who could play on the firms’ baseball teams. I worked and played for a variety of industries across the Northeast, including a snuff factory in New Jersey and a shipyard in Connecticut. I once took a job with a cotton mill in Rhode Island, but quit after just three days. Most of my coworkers in the mill were children, as young as ten. They labored sixty hours a week for forty cents a day, breathing air that was foggy with lint. I was getting twelve dollars a week to play baseball. My conscience couldn’t reconcile itself with the unfairness, so I left. I knew my departure didn’t help those kids any, but I liked to think that it hurt their employer by weakening the company team.

During those semipro years, I sharpened my playing skills, learned to get along with different kinds of people, and picked up the rudiments of a dozen industrial trades. My only book-learning came from what I read while killing time in railroad depots: dime novels, The Police Gazette, and The Sporting News.

I made it to the minors a year ago, and played most of the season with Providence until the Braves bought my contract. To my delight, old hurler Cy Young was on the team, playing his last season after more than twenty years and five hundred victories. The highlight of my stint with the Braves was that someday I could tell my grandchildren that I had been a teammate of Cy Young.

I had always assumed that once I made it to the majors, I would stay there. It didn’t occur to me that I could head down the system as well as up, and I was devastated when the Braves released me after the season. At age nineteen, I thought my career was over.

But now the Red Sox were giving me another shot at the big leagues, and I intended to make the most of it.

A sharp cough snapped my mind to attention. I looked up to see the stadium attendant I met yesterday standing next to my seat. He wore a navy suit almost identical to his uniform, with a red polka dot bow tie protruding from a high tight collar. I was startled to see him on the train—surely the Highlanders and Athletics had ushers for their own ballparks.

“I don’t believe I ever introduced myself,” he said, extending his hand. “My name is Jimmy Macullar.” I took his grip. “Mind if I sit down?” I shook my head, and he gently settled into the seat next to me.

In a low voice Macullar said, “I was feeling badly about yesterday.” The bumping train caused his words to rattle softly through his teeth. “It’s a terrible thing that happened. You must have been very shaken up.” He looked at me sympathetically as I murmured agreement. Considering my embarrassing physical reaction to the situation, I thought him gracious in understating my condition as “shaken up.”

“One way or another, I’ve been in baseball more than forty years,” he said. “I don’t go back quite as far as Abner Doubleday, but I’ve seen just about everything in the game since then. I want you to know that I’ve never been as excited about any team as I am about the 1912 Red Sox. Even before the season started, it seemed like everything was coming together for us. We already had the players, and now the new owners have taken care of everything else.

“Stop me if you like, but I thought you might want to know something about the ball club.” I didn’t stop him, so he went on. “A new group of owners bought the team last year. Some of them had been players, some managers—all of them have a solid baseball background. They know the game on every level.

“You met Bob Tyler. He’s the treasurer and general manager—handles all the day-to-day business decisions. I’m his assistant and sometimes I help out at the gate or do odd jobs. Mr. Tyler used to work for Ban Johnson—”

“Really?” I interrupted. I couldn’t picture Tyler working for anyone but himself—although if anyone could order Tyler around, it would be the American League president. “What did he do?”

“Mr. Tyler was the league secretary for six years. He knows more about league affairs than anyone but Ban Johnson himself.

“Jake Stahl is quite a man, too,” Macullar said. “I think you’ll like him. He owns about ten percent of the club. Player, manager, and owner all at the same time. It’s a lot of responsibility, but he handles it well.

“Anyway, what I wanted to say is that we have the ideal owners for a baseball club. They know the game from the playing field to the league president’s office. The first thing they did was move us out of the Huntington Avenue Grounds, and put up Fenway Park. Beautiful ballpark isn’t it?”

I shook my head up and down in unrestrained agreement.

“Opening Day at Fenway was a grand time—the game was postponed three days by rain, but that just made it more exciting when we did get it in. Mayor Fitzgerald and his Royal Rooters were there in force. They kept singing “Tessie” over and over—that was our fight song in ought-three when we won the first World Series.

“Anyway, we beat the Highlanders 7–6 in extra innings opening day. I took it as a good sign for the season. It seems like the whole city is excited by the team. Of course, with Honey Fitz our biggest fan, everyone is eager to get behind us.” I deduced that Honey Fitz was the mayor of Boston.

“Well, I’ve talked too much,” Macullar concluded. “Mr. Tyler asked me to bring you to his car, but I wanted to take a few minutes to let you know that this is a very special team, and you have a lot to look forward to.” He smiled confidently. “We’re going to the World Series.”

Macullar rose to his feet. I stood up and followed him through the train, wondering why he had made such an effort to talk up the team’s ownership.

We both entered Bob Tyler’s private car. Tyler was seated in a plush chair, his hands folded on the large gold head of a walking stick that stood between his knees. He glared at Macullar, silently asking, “What the hell took you so long?” Verbally he told him, “That will be all for now, Jimmy.” Macullar quickly ducked out of the car.

In addition to the cane, Tyler had an aggie-sized diamond stickpin in his tie and a hefty gold watch chain draped across the vest of his striped brown suit. Buff spats covered his ankles. He reminded me of some of the factory owners who used to hire me to play: petty autocrats who thought they could impress the world by sporting the sort of trappings I now saw before me. Usually, the most adorned and pompous men ran the shabbiest factories.

I was in my one good traveling suit, which was still grimy from yesterday.

Tyler pointed me into a seat, and adopted a grave tone. “Mickey, Captain O’Malley’s investigation isn’t going very well. In fact, he seems to think you’re the leading suspect.”

“But I didn’t have anything to do with it! All I did was find the guy!”

“Well, if it’s any consolation, I believe you.” With a grimace, he added, “I never heard of a killer who pukes on a man he’s just murdered. I’m not the police though—it’s their opinion that counts. And you were found at the scene of the crime.” Tyler allowed me to squirm uncomfortably. I stared at his face, and noticed with some surprise that he was younger than I thought at first; he probably wasn’t out of his forties. His brown hair was thick, without a hint of gray. From his dress and bearing, he wanted to appear older—to bolster his autocratic manner, I figured. He finally went on, “However, I’m not without influence. The team does have a certain status in the city of Boston, and we can probably protect you somewhat from any hasty accusations by the police.”

“But why would I need protection? I didn’t do anything wrong.”

“You’re a major-league baseball player. You’re in the public eye now. If he wants to, a cop or a reporter could get a lot of attention for himself just by accusing you. That kind of publicity tends to stick, though, and that’s bad for all of us. The point is that a ball club can do a lot to protect its players.” Tyler glanced up at the ceiling for a moment. Then he said in a confidential voice, “I’ll let you in on something: every couple of years, Ty Cobb gets in one of his rages and assaults somebody. Then Frank Navin has to calm down the cops and try to keep it out of the papers. You remember when the Tigers played the Pirates in the World Series?”

I nodded. It had been just two or three years ago.

“Cobb had to travel outside the Ohio border every time they went from Detroit to Pittsburgh. You know why?”

I shook my head.

“Because he knifed some hotel worker in Cleveland, and there was a warrant out for his arrest. Navin took care of it in the off-season. He’s a good owner. He takes care of his players’ problems. If the Tigers can keep it quiet when a famous player like Cobb really commits a crime, we should be able to protect a nobo—a, uh, lesser-known player who was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. You’re going to have to do your part, though.” I started to ask what that was, but he talked over my question, already answering, “You don’t say anything to anybody about anything that happened.”

“But what about the police? What if they want to ask me more questions?”

“Of course we want to cooperate with the police—just like we expect them to cooperate with us. If Captain O’Malley has any questions for you, you should answer them—just make sure I’m there, too.”

“You mentioned the papers. I saw today’s paper and there wasn’t anything about it.”

“Well ... Boston’s a big city. People turn up dead all the time.”

“At Fenway Park?”

Tyler looked annoyed. “We wouldn’t want Fenway to be mentioned, would we? Look. Nobody even knows who the man was. I don’t know if this occurred to you, but he may not have been some innocent victim. What if he was killed in self-defense? What if he was a hoodlum who had it coming? Look. This is what it comes down to: you don’t need trouble, the team don’t need trouble. The cops will do their investigating, but they’ll have to do it quietly. If O’Malley wants to talk to you, that’s fine—I’ll just come along and make sure your interests are protected. Other than that, you don’t say a word to anybody. Understood?”

I didn’t feel like I understood, but I nodded that I did.

With a forced smile Tyler said, “Good. Let’s get this behind us, and concentrate on baseball. Jake’s probably going to start you in tomorrow’s game.” He clapped his cane on the floor to signal an end to the conversation. “Send Jimmy in on your way out.”

I did as he asked and returned to my seat. I wasn’t able to get my thoughts on baseball, though, so I fruitlessly mulled over Tyler’s words. This business with the police and the papers and the ball club was beyond my experience. I could make no sense of the situation.

But I could tell that this didn’t look like it was going to be my season.