Читать книгу The Forgotten Japanese - Tsuneichi Miyamoto - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Folksongs

Оглавление[Tsushima Island, Nagasaki Prefecture, July 1950 and July 1951]

As I had been delayed in the village of Ina, it was after five o’clock when I departed. Even though it was summer when the days are long, the sun was already on its way down. From Ina to the back end of Sago is a little over seven miles. Although I couldn’t be sure, if I hurried I might just be able to arrive with a little daylight left. At any rate, I departed with the thought of hurrying, and then someone from the place where I’d been staying came chasing after me. “Some people came to Ina from Sago to buy wood, and since they’ll be heading back now it would be good to join them.”

When I reached the edge of the village, three men stood there talking, their horses tied to a tree. Seeing me, they said, “So you’re the one that’s going to Sago. If that’s so, how about making the trip on the back of a horse? Today we came here thinking to buy some lumber, but since it hasn’t been cut yet we’re going back light in the rear.” I was grateful, but being poor, after calculating the cost of riding, I declined. “Then we’ll tie your shoulder bag on one of our horses,” they offered, so I had them strap my rucksack on. “You walk on ahead,” one told me. “We have to buy some gasoline to take back, and we’ll catch up with you directly.”

I set off hurriedly, relieved of my burden. After Ina, the village of Shitaru appeared and the evening sun on the ocean inlet there was beautiful. While I was walking on the road along the shore, the three men on horseback came up from behind and passed me, looking gallant. It was just like in the drawing of farmers off to get fish, running their horses, in the legend of Ishiyama Temple. They were dressed in light, short-sleeved kimonos, drawers down to their knees, and straw sandals.

It was all fine and good to look admiringly at their retreating figures, but in almost no time they’d disappeared from view. Relying on my map, I passed through Shitaru and started along a road through the mountains, but the men on horseback were nowhere to be seen. Completely at a loss, I asked someone working in a field if anyone had passed on horseback. “They were going at quite a pace,” he replied.

I had thirty-three pounds of rice in my knapsack, along with a change of clothes. Much like in medieval times, one had to carry rice to travel in Tsushima in 1950. Without this rice, more often than not, I’d have been imposing on the farmers I stayed with, for in Tsushima rice was scarce. That aside, I’d not asked the three men their names, or where in Sago they lived. The valley in Sago runs about two and a half miles north to south, and there are six tiny villages in that stretch. I thought things looked bad, but anyway I’d try walking as far as I could. If I took a wrong turn I could always sleep out in the mountains.

In May of that year, when Izumi Sei-ichi (a professor at the University of Tokyo) had come here to do preliminary research, he’d gotten lost on the road from Sago to Ina. He’d set off from Sago past noon, thinking he’d easily come out in Ina by evening, but he had become utterly lost, and didn’t arrive in Ina until ten that night. Izumi-san had warned me, “In many places in the north of Tsushima, the narrow road is the main one, so you have to be careful.” I could see that it was just as he’d said. When I came to places where the valley narrowed and, moreover, where the road divided into two, I was suddenly at a loss. There were no signposts or anything. So I tried walking both roads and looked for the presence or absence of a horse’s hoof. Then I took the road with the hoofprints.

Walking along in this way, it occurred to me that this was probably what the roads had been like in medieval times and before. In addition to being narrow, the road was overgrown with trees, and without the slightest chance of a view there wasn’t even a way to confirm where I was. I can well imagine taking the same road many times and still getting lost. Until you’ve walked a road like this, it’s hard to understand those stories about people being led astray by foxes and raccoon dogs [an animal related to dogs and wolves but more closely resembling the raccoon in appearance and temperament]. And at night these roads are absolutely unwalkable. The sun was probably still shining on the upper slopes of the mountains around me, but this narrow valley road was already as dark as night.

Walking along, I could hear voices somewhere. It sounded like they were calling out. For all I knew they were calling me, so I tried calling too, in a loud voice. And while doing this, I walked in the direction from which the voices had come. I climbed up the valley and came to a pass. But even up there, as the forest was dense, there was no view at all.

At the top of the pass, the three men were waiting, their horses tied to a tree. I paused to catch my breath, and when I said rather emotionally that it was no easy task to walk the roads in these mountains with absolutely no visibility, an old man of nearly seventy said, “There’s a good solution for that. Speak out, so others will know you’re walking here now.” When I asked him in what manner I should speak out, he answered, “Sing. If you’re singing and someone else is on the same mountain, they’ll hear your voice. If they’re from the same village, they’ll know who it is, and they’ll sing too. If the person is near enough that you can make out the words, then you call out to them. By simply doing that, each knows at least the direction the other is heading, and what they will be doing there. So if you get lost, as long as someone has heard you singing, they can imagine what happened and where.” I found that to be rather convincing and realized that a knowledge of folksongs is necessary when walking a mountain road such as this one. When I asked the old man if he would sing, he replied, “Let’s wait until we’ve started walking again,” and mounted his horse.

The road descended through uneven rocks. Astride his horse, the old man held the reins with one hand and the saddle with the other to keep his body from sliding forward and falling, for although there was a saddle it had no stirrups. He explained that the reason for the absence of stirrups was to reduce the chance of an injury; in mountains such as these, one can get thrown from a horse if one gets caught up in the drooping branches. Walking together like this, I came to feel that the folksongs these people sang and every detail of the way they rode their horses were accumulations of a deep wisdom about life itself.

Then, sitting on that unstable saddle, the old man began to sing. And from the moment he began I was struck with admiration. This was definitely a packhorse driver’s song. It was not rhythmical and refined like the songs of the Matsumae and Esashi packhorse drivers, which have become parlor songs. It had the simple artlessness of a horseman’s song, and although the old man was approaching seventy, his voice truly carried well. Atop his horse, he seemed to be lost within his own song. I followed him, running along behind.

When the road became a little better and the valley more open, we came upon a village called Nakayama. The houses, about ten in all, were scattered here and there among the fields. Though the sun had already gone down, none of the houses had lit their lamps yet. At every house the people could be seen out front, putting things in order or talking. The red fire burning for a bath at one house made an impression on me. A young man stood in front of that home, removing dirt from a hoe.

When the man on the horse asked the young man if he wanted to come over, he responded, “At Bon.” This being Bon on the old calendar, the festival would be some ten days later. “You haven’t come much this year.” “Yeah, the last time was in May.” The young man stretched his back and looked at us. He was a bright, round-faced, and sturdily built youth. While it was nearly five miles from Nakayama to Sago Valley, these were neighboring communities. Yet he was saying that since New Year’s, he’d only been to Sago the one time in May. There’s no radio or newspaper, no Saturday or Sunday. Life here is still without plays or movies. When I asked, “Do you spend all your time working?” The old man answered, “No, we make a picnic lunch and go over to Chuzan (a village on the coast) for shellfish in among the rocks, and to fish. We have fun.” Another of the men on horseback said, “This old man has a good voice, so he’s had quite a lot of good fun.” I thought this was because he was enraptured with his own singing and that this had brightened his life, but there was another meaning to what the man had said.

We continued on from Nakayama along a valley road, and at the upper reaches of the Sago River the road descended alongside the stream. Sometimes on the right bank, sometimes on the left, the road passed on whichever side offered even a bit of flat ground. In many places I had to traverse the river from right to left or from left to right, and each time I would pull off my shoes and socks, roll up my pants, and make the crossing barefoot while the men on horseback splashed their way across. When I reached the other bank, I would hurriedly wipe my feet, put on my socks and shoes, and run after them, for they’d have already gone far ahead. Soon I was exhausted, completely out of breath.

I’d not eaten lunch. Even here on Tsushima if I stayed at an inn I’d be given breakfast, lunch, and dinner. But when I asked farmers to put me up, while they’d eat breakfast and dinner, many ate no lunch to speak of. It was rare to have any meal that was worthy of being served on a tray. When the farmers were hungry, they’d eat whatever was on hand. Most of them didn’t have watches. Even if for argument’s sake they did, they didn’t have radios or the like, so there was no fixed time. Families with children in elementary school would have some notion of time, but the average farmer wasn’t bound by what we call time. When I broke my watch during my travels, I came to know what the world was like without one.

Because I was traveling to study Tsushima for the Federation of Nine Academic Societies, when I had left Izuhara, the island’s main town, I’d been provisioned with a little more than thirty-three pounds of rice, the amount necessary for the completion of my research. But actually a fair amount had been taken out. The archaeology team had to employ laborers, and they had to be given food. Since allotments hadn’t been made for them by the food supply office, deductions were made from those of us who were on the island for long-term research. I had received a per-day ration of one pound of rice, so as a rule I had to skip lunch.

When I walked the island, I did my best to stay with farmers, and for lunch some of them made do with sweet potato powder, others with nothing at all. In one house where I was asking questions of an old man, he didn’t eat lunch, even when midday had come. When I suggested that he eat and that we could talk afterward, he answered, “I’m not working today,” and made no move to eat. The idea of “no work, no meal” seemed to be alive and well in this area. So when I was able to buy sweets, I’d make do with them for lunch, but in Ina I’d skipped lunch altogether. On this trip, however, getting up at six every morning, listening and taking notes until midnight or one, and copying old documents, no matter how excited I may have been, the fatigue was merciless. And what is more, since the top of the pass I’d been at a constant run for more than two and a half miles. If I hadn’t run, I could not have kept up.

At last I’d become desperate, and while crossing the river I put my face in the water and drank with abandon. I took off the wing-collared shirt I’d been wearing and my pants and wore only my undershirt and trunks. Dressed like this a little sweat wouldn’t hurt. I balled up my shirt and pants, tied them with my belt, and slung them over my shoulder. Wearing my heavy work shoes and looking rather heroic, I ran on once again. Because I’d fallen a little behind, I heard one of the men call out to me. When I caught up they asked, “Are you tired?” “What? No!” I dissembled, though I was having a bit of a rough time of it.

What appeared to be a five- or six-day moon was now in the sky. It was approaching half full, and the night road was bright.

The old man had sung the horseman’s song for the better part of an hour atop his horse. Tripping along after him, I ventured to ask, “Are there also Bon dance songs?”

“No, Bon dancing has already faded away.”

“But the songs are still around, aren’t they?”

“It’s not that they’re not, but . . . ”

“Then, one of those.”

“Well, then one epic ballad . . . ” agreed the old man, and he then began a Bon epic, the Oeyama Epic. It was a truly quiet song and seemed to contain an old Buddhist tale.

According to my grandfather Ichigoro, the Hyogo Epic was the oldest. And I’d heard that his own song pulled water, so to speak, from the stream of the Hyogo Epic, but I’d never dreamed that I would hear, from an old man in the valley of Sago, in the north of Tsushima, a song almost no different in cadence from my grandfather’s. The Oeyama Epic tells of when Yorimitsu slays the young man Oeyama, who takes the guise of a demon and steals from others, and it’s thought that the lyrics of this song are relatively old.

The old man also sang the Otsuya Seishin and Shiraito epics, among others. And finally we came to where we could see the light of fires in the homes in the valley of Sago. Every time we passed in front of a house, the horses whinnied. The ones the three men rode were all males. And at every home, a mare was tied. With each house we passed, the stallions were drawn to the mares and tried to head in their direction. There is a line in a haiku about “a horse neighing when a horse passes,” and it was just so. There’s a knack to pulling in the reins when passing in front of a home, and it was no time for a song. Anyway, I’d arrived in Eko, in Sago Valley, having run more than seven miles. The man who’d helped me with my load said, “Tonight come to my house and spend the night,” so I parted with the other two and settled in at a farmhouse in the middle of rice paddies. And that night I listened to stories about the valley of Sago until after midnight.

The next day, I visited Old Man Suzuki who, already four years over eighty, was said to be the best singer in the valley. He was behind his house in the shade, making grass sandals. “Grandpa, I heard you’re the best singer in Sago, so I’ve come hoping you’d give me a chance to listen.”

“Where are you from? You say you’re from Tokyo? That’s where the emperor lives. These days the emperor has come on hard times.” After that we talked of various things and gradually, in time, he appeared to be in good spirits. Saying, “Maybe I’ll sing one song,” he started the Oeyama Epic. He was old and got out of breath, but definitely sang better than the old man of the night before. He had a practiced voice and could truly turn a verse. In places he even resembled one of those ballad singers accompanied by a samisen. I sat cross-legged on the ground, listening with my eyes closed. When he’d sung to the end, he simply said, “I’m out of breath, it’s no good,” and didn’t make a move to sing any more thereafter.

On the island of Tsushima there are six miracle-working goddesses of mercy. Traveling to worship these six Kannon first became popular around the end of medieval times. Men and women would form groups and go on a pilgrimage. In Sago there was also a hall for the Goddess of Mercy, and these flocks of pilgrims would come along and stay in the people’s homes. When this happened the young people in the village would go and sing, in turns, with the pilgrims. They competed based on the quality of a verse or a phrase, and in the end they would bet all sorts of things. The men would even make the women wager their own bodies. Apparently it was rare for a woman to ask a man to bet his own body, but at any rate, they would go that far. Old Man Suzuki had never lost in such a sing-off with the women. And, it was said, he had slept with nearly all of the beautiful women who had come along on pilgrimages. That was what had been meant the night before about the old man having enjoyed himself because he sang well. Anyway, in the north end of Tsushima, young men and women sang and danced together until around the end of the Meiji period. A fire was lit in the yard in front of the house where the pilgrims were staying, and the pilgrims and village youth would have sing-offs and even dance-offs, forgetting the passing of the night. At such times no distinction was made between married and unmarried women.

Songs were not just sung. They were accompanied by movement and sung back and forth. No doubt Old Man Suzuki was not only in the possession of a good voice but was also the most skilled in these parts at all the rest as well.

In the following year, 1951, I returned to Tsushima for research. I heard the most folksongs in Sasuna, near Sago. One evening I arrived in Sasuna, together with Shibusawa-sensei, chief of this research, and the women of the village performed a Kabuki dance for us. They sang each passage of the story of Chushingura, and the dance with which they accompanied it was truly refined. I became friendly with the old woman who sang. Remarking that I thought this area should have a lot of songs, I asked if she might sing for me. She consented with pleasure, and told me to come over that night.

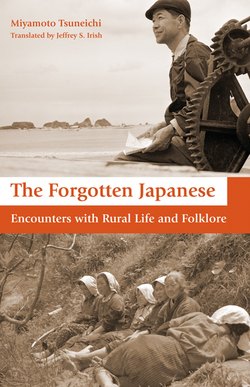

The women who sang for Miyamoto, seeing him off at

the local pier. July 1951.

After finishing dinner at the place I was staying, I waited. When it had grown late, she came to get me. I went along carrying a bottle of sake. Four grandmothers, all over sixty, had gathered, and there were young people there as well. One of the older women said, “First you’ve got to start things off by singing,” so I sang a verse from the Bon festival dance from my hometown. They said that it was much like their own, and the grandmothers happily began to sing. To moisten their throats I poured them sake, and they drank freely. That was when the singing really started. Their voices were pretty. Thinking that if I took out my notebook I’d ruin the mood, I decided only to listen. When one woman had sung and grown short of breath, the next would begin. Many of the songs were from the Kabuki stage, and there was always dancing with the hands. Moving their hips, standing on their knees, although they danced only with their upper bodies, they radiated beauty from deep within. I was unable to see them simply as old farming women.

The young, seated men were attacked and disparaged by the older women, who called them artless monkeys. I learned that Bon festival dancing had thrived in Tsushima and that there was Bon dancing in nearly every inlet, up every creek. During this Bon dancing, they also had a scene from Kabuki, and it had become an important occasion for the learning of folksongs as well. But in Sasuna, for some reason, Bon dancing had fallen out of practice. This, it would seem, had reduced the number of opportunities for the elderly to pass on their knowledge to the young.

When the old women had sung, they demanded a song of me as well. I don’t know all that many songs, but for every three times they asked, I’d sing once. This, I thought, is how singing competitions came to pass. As the singing became more excited, more and more of the lyrics had to do with sex. The young people shrieked with elation, but the old women remained relatively composed. It had grown late, and the singing voices were loud, so people in the neighborhood gathered in front of the house. The singing continued in this way until about three. Of course, during that time there was also animated conversation. And so it was that I first came to have a notion, though faint, of what sing-offs in these parts had been like.