Читать книгу The Forgotten Japanese - Tsuneichi Miyamoto - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Grandpa Kajita Tomigoro

Оглавление[Tsushima Island, Nagasaki Prefecture, July 1950]

I called on Grandpa Kajita Tomigoro on a clear, bright morning late in July 1950, in the Azamo section of Tsutsu Village, on the island of Tsushima. Earlier at the post office, in the course of a conversation with the postmaster about various aspects of this village, I had learned that only one person from among the village’s first settlers was still alive. That was Grandpa Kajita. “Try visiting him,” the postmaster encouraged me. “He’s over eighty, but in good health, and he’s quite capable of conversation.”

Here was a person who had watched a village grow from its very beginnings. This was really something. I took my leave of the postmaster and went to visit the home of Grandpa Kajita nearby. He had retired from his position as head of the household and was living with his elderly wife. His son lived in the house just below theirs, where he also ran a confectionery store. I found Grandpa sitting and making fishing tackle on the wooden floor of a house that was blackened inside by the soot from wood fires.

I greeted him, saying, “Grandpa, I hear you were born in Kuka, in Yamaguchi Prefecture. I’m from Nishigata, to the east of Kuka. So I feel nostalgic, coming to visit you . . . ”

“Really, you’re from Nishigata? You’ve come a long way,” he mused. “It’s been ages since I’ve been to Kuka. I imagine it’s changed a lot.”

The old man spoke entirely in the language of my home, so right from the start he didn’t feel like a stranger. And when I said, “I was thinking maybe you could tell me about things from the distant past . . . ” he started to speak without hesitation.

It was long ago that I first came here. I was seven at the time, and I didn’t know east from west. I’d had bad luck with my parents. My father had died on me when I was just three and my mother around that same time. My brothers all died young as well, so, as for relations, I had just one grandmother and she took me in. Then, as it happened, there was a man named Masamura Jisaburo who didn’t have any children; he said he’d try raising me, so I went to live with him and stayed until I was seven. I don’t recall much from my childhood. My grandmother’s family, they were confectioners. Sometimes I’d go there and be given a toffee to lick, and I looked forward to that.

You ask how it is that I came here to Azamo? Well, they had what were called meshi morai [literally, “food receivers”] on Kuka’s large fishing boats. It was custom to put five- or six-year-old orphans on these boats, and I was placed on one too. As fishing boats go these were large, with five or six people on a vessel. But they didn’t fish off the coast of Kuka. Instead, they all went far away. Since way back, Kuka’s fishermen had been going to Tsuno Island in Nagato to fish for sea bream, half a dozen boats to a group. The oldest among these fishermen would become the “big captain” and when they went over to Tsuno he did all the bargaining with the people there, and decided both where they’d fish and where they’d lodge at night. After that everyone worked as they pleased. Then, when it came time to return, all of the crews and the locals would gather together to talk and the big captain would address the people of Tsuno Island, saying, “There were no troubles, so all went well.” And the fishermen would all return to Kuka. On the way, their boats traveled in pairs and helped one another out when there was an accident.

They didn’t just go to Tsuno Island. Some fishing crews went to Karatsu, too, on the west side of Kyushu. And in time they were even able to go to Tsushima. The Kuka fishermen were the first to make the journey. I’ve heard that, long before I was born, a feudal lord from Hiroshima married off his daughter to Lord So Sukekuni in Tsushima. After that, people started to go back and forth between Hiroshima and Tsushima, fishermen included. Crews from Hiroshima would come and fish off the coast of Kuka and probably the guys from Kuka heard their big stories right there because the Kuka fishermen came back with some tall tales. The visitors claimed there were fish in Tsushima that were fabulously large, and that the sea was filled with fish. Well, if there were that many fish, the Kuka fishermen wanted to go too, and so they followed the crews from Mukainada, in Hiroshima, and crossed over to Tsushima. That was all more than thirty years before I was born.

As it happened, the boat I was put on was going to Tsushima. I’ll never forget. It was in 1876. We left Kuka and it took any number of days before we arrived here. On windy days, we’d attach a tiny sail to the bow of the boat. When there was no wind, we’d put the oars in. When we got as far as Hakata, we took on miso, soy sauce, salt, and rice. Then we waited for good weather on Genkai Island, at the mouth of Hakata’s harbor, and when we thought the weather would hold for a few days, we departed. My young mind couldn’t believe that the first boat I’d ever been on was suddenly going to Tsushima. The little town of Kuka had been my playground, and now wherever I looked there were only waves. The boat wouldn’t stay still. We were rocked up and down and it was more than I could bear, so I held on to the side and just watched the big waves. The adults were something else, rowing along on the tops of those big waves. They rowed even at night, and I was relieved when we arrived at Iki Island. Climbing up on the hill at Katsumoto, on Iki, we could see mountains far to the north. When I was told that this was probably Tsushima, I was discouraged to think we still had that far to go.

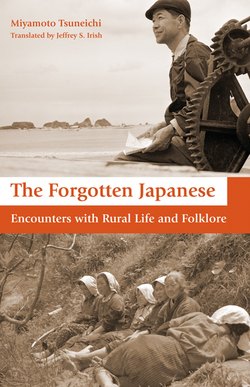

Boy sleeping on fishing nets. Yamaguchi Prefecture.

August 1962.

As an orphaned child taken aboard, I didn’t have any work to do. I was supposed to just play quietly on the boat. It was so small, though, and there was really no way to amuse myself so it did get boring, but the fishermen all doted on me and I somehow made it through. On the boat, when night fell, I’d take a cloth patchwork kimono from the stern and, covering myself with that, would burrow down under the rush mats. On rainy days, I’d make a roof of these rush mats and do nothing but sleep all day.

We were in Katsumoto for a number of days waiting for fair weather again, and then after a full day at sea we arrived in the castle town of Izuhara [on Tsushima]. I was amazed to find a town like this on an island at the other end of the sea. In those days some of the homes in Izuhara had tiled roofs but many still had rocks on their roofs. The feudal lord made his rounds of the island on horseback. He wore a hat and an open-backed half-coat and was a truly splendid sight.

It must have been around the time of the fall festival that we arrived in Tsushima. We’d left Kuka after Bon, but the weather was bad and it had taken the better part of a month.

We contracted with a seafood wholesaler in Izuhara, and because he was going to build a storage shed in Azamo that year, the boat I was on came here. Nowadays, Azamo is a fine, civilized town, but when I first came here, this bay was all dark and grown up with trees. See that grove of chinquapin trees across the bay, those big trees growing packed close together? In these parts, trees like that were growing all over. And there were big rocks in the bay, so it wasn’t the kind of place you’d moor a boat. What’s more, there were no people. The trees grew right down to water’s edge, so close that their branches touched the sea. There was just one shed atop the promontory at the border of Azamo and Little Azamo, and it looked like it might blow over. Someone from Hirado had put in a net for yellowtail just below, and the shed was for the net’s caretaker.

Properly speaking, Azamo was in a forest dedicated to Priest Tendo, so people were not supposed to live here. Around here, such places were called shige, and the people really feared them. They’d say, “That’s Tendo’s shige so you shouldn’t live there, you mustn’t do anything that will defile it.” The beach in the back of the bay was called “No Admission Beach” and no one was permitted to go there.

You ask why it was that people from Kuka came to live in such a place? There were a lot of samurai in Tsushima, and traditions were strictly observed in all the villages. We fishermen didn’t have etiquette or manners, so we weren’t able to associate with others there. It didn’t matter to us if we suffered divine punishment, and figuring it would be best to just live amongst ourselves, with people who got along well, we decided to build a shed in Azamo and live here.

So you want me to talk a bit more about what happened before that? Well, anything earlier was from stories I heard from the grown-ups so I don’t know much. Tsushima is near Korea, and I heard that the Japanese often went to Korea secretly [because Japan was still closed at the time], to buy ginseng. I often heard about ginseng. It was really costly, and what you could hold in the palm of your hand was worth many gold pieces. It just wouldn’t grow in Japan, so people went secretly to buy it.

The moneychanger Gohei was the boss. People would refer to “the moneychanger of Kaga,” or to “Kaga where the moneychanger is.” Gohei was a shipping agent and the wealthiest man in Kaga. When he came to Tsushima, he wore a Japanese kimono and raised a Japanese flag, but when he’d passed Tsushima he raised a Korean flag, wore Korean clothing, and, having become a Korean, made the crossing. Aside from the moneychangers, there were more Gohei imitations than could be counted. Eluding government officials located in Tsushima, they went to Korea as well. And there were far more of them than the government could handle.

The government placed a lookout on Teppo [Gun] Point, west of Azamo, on the southwest end of Tsushima. When they sighted a fishing boat that had set out rowing west from the Ko Peninsula, which juts far out into the ocean east of Azamo, they’d fire a warning gunshot into the air. If the boat didn’t start back east, they’d come rowing out of the Tsutsu Bay in a longboat. These boats were narrow and long. They had eighteen oars and were so fast it seemed they were flying. They’d even beaten steamships in a race. With all those oars, they were also called “centipedes” and everyone feared them.

GRANDPA KAJITA’S TRAVELS

When the gun was fired from Teppo Point, the rowers in Tsutsu Bay would ready themselves. When a second shot was fired, they’d come out rowing. Nearly all the fishing boats were caught. And when they were caught, they were taken to Izuhara and subjected to water torture. They’d force the fishermen’s mouths open and pour water in and they’d choke. It was more painful than a person could bear. Fearing that, the fishermen did their best not to go west of Ko Peninsula.

As it happens, nearly three miles out from Ko Peninsula there was a place called Ose, the number-one fishing spot for sea bream in Tsushima. There were big fish there. At times they caught sea bream there that were three feet from eye to tail, bigger than any you might see these days. It was that kind of fishing spot, so everyone went. And before they knew it, the wind and tides would take the fishermen out to the west. A gun would go off, the longboat would come along, and they’d run for it, scattering like baby spiders. Those who fell behind were caught, and though they’d committed no crime, they too were subjected to water torture. It was like dancing on the edge of the boiling pot of hell.

When night fell, the fishermen would anchor and spend the night east of there, off the coast from Naiin, in the shadow of Naiin Island. They called that place “Sails Down,” and it was the best-hidden anchorage.

Then, after the Meiji Restoration [1868], fishing boats were allowed west of the Ko Peninsula. The Kuka fishermen jumped for joy. The sea bream there were coming from the west so, without a doubt, there were even more sea bream off the coast from Tsutsu, and that’s where all the fishermen rushed to be. Sure enough, the fish were there for the catching. The ocean was full of them. The people of Tsutsu allowed fishing offshore, but didn’t permit people to moor their boats there, so when night fell these fishermen would go back to Naiin Island.

Well, one day something terrible happened. It was December 15, 1872. The sun had sparkled a bit in the morning, and when it sparkles, a wind will come up. Not thinking much of it, though, the Kuka fishermen headed out, offshore from Tsutsu. Past noon, a terrific northerly began to blow. They say the air grew damp and salty, and Tsutsu, right there in front of their eyes, grew dim and hard to see. They rowed for Tsutsu with all their might, but nearly everyone was swept out to sea and died. Altogether forty-four people went missing, and the great Katsuemon was among them. The man was thought to be a fishing god. Katsuemon could look at the weather, the tide, at fish . . . he was never off the mark about anything having to do with fishing. But even Katsuemon died, and to this day that storm is referred to as the Katsuemon Storm.

Most everyone living along the sea between Kuka and Tsushima knew Katsuemon. If someone mentioned “Katsuemon from Kuka” others would think, “Oh, the fishing god.” If someone asked Katsuemon, “What’ll the weather be tomorrow?” ten times out of ten it would be as Katsuemon had said. But even Katsuemon was capable of an oversight. Apparently he’d said, “What an unpleasant day!” on his way out, and he never came back.

The people of Tsutsu were hard on outsiders, but they were all good people and they held a memorial service at the Eisen Temple for the forty-four who had died. And to this day, the souls of the dead are enshrined there. Sometimes, on the night of December 15, the people of Tsutsu see the spirits of the forty-four fishermen walking in from the sea, towards the Eisen Temple.

But even after such a large accident, the people of Kuka didn’t stop coming to Tsushima. It’s said that on that day, one of the boats had capsized and drifted away with a father and son clinging to it. They were exceptionally lucky, for they drifted and drifted, to the ocean off Hirado, and were saved by the people there. This father and son returned to Kuka and told others, “Our boat capsized because waves came in over the bow and stern. Mount wide boards in your bow and stern, and your boats will be stronger in the waves.” After hearing this, fishermen started doing just that. And when waves rose up they spilled back to the sea and didn’t swamp the boat. In any case, after that, there was never an occasion when as many as forty or fifty people died.

There’s an explanation for why we came to live in Azamo. The year before I came to Tsushima, in December of 1875, an eight-oared longboat from Tsutsu went to Izuhara to make a payment to the authorities there. When they were on their way back, a terrible westerly blew, and they were beaten by waves and overturned off the Ko Peninsula. They were found by a large fishing boat from Kuka which, after uprighting the longboat, rowed back to Naiin, nursed the crew, and brought them back to Tsutsu. The people of Tsutsu were overjoyed and they said, “We’re truly in your debt. As a token of our thanks, we’ll do whatever you ask of us.” So the people from Kuka said, “In that case, can you allow us to live along the Azamo Bay?”

“We can do almost anything you ask for,” they replied, “but that place is shige and you’d be cursed.”

To which the Kukans said, “It doesn’t matter if there’s a curse. Besides, now we’re living in an age where a living god, the emperor, rules Japan, so Priest Tendo won’t do us any harm.” So, with permission to build a shed in Azamo, they returned to Kuka.

The following year, the year they built a shed here, that was when I first came. When I say we built a shed, that was not something we fishermen could do. First, a merchant from Izuhara named Kameya Hisabei came, felled trees, cleared the land, and built a shed. The roof was made of cedar that had been cut down and split into boards. Bamboo was then placed over these cedar planks, with rocks on top of that to hold it all in place. The shed’s posts were made with logs that were sunk right into the ground, and its walls were lined with straw mats. There wasn’t a floor—just straw mats placed on the ground—but just the same, the place made me feel like a lord. Until then, every day I’d only been living on waves. I’d wake to the sound of them striking the side of the boat. It’s nothing when you get used to it, but as a child of seven I wanted to try sleeping in a house on land.

I’ve been calling it a shed, but it was really more like a storehouse. A clerk and apprentice came from Kameya’s store in Izuhara, and they’d buy the fish we caught, gut them, salt them, and take them back there. Most every day a boat would come from Izuhara, and when they did, they’d bring the kind of things fishermen want: rice, miso, tobacco, and the like. We’d come back from sea, enter the shed, and buy the various things we needed. After that, everyone would sit indoors by a fire that burned quietly in the sunken hearth and talk late into the night.

All the talk was frightful for a child, for fishermen’s stories are all about encounters with rough seas. And in the old days, for some reason, there were lots of monsters. Off the coast of Kuka, on a drizzly night, like clockwork, a voice would come up from deep down in the ocean, saying, “Give me a ladle, give me a barrel.” That was the cry of a sea monster, and if you gave him a ladle, he’d use it to fill the boat with water and sink it. And Genkainada [a stretch of ocean between Tsushima and the Kyushu mainland] was a place where sea spirits often appeared. Everyone delighted in the telling of such stories, but we small children were seized with fear.

I wasn’t the only orphan who had been brought along. Every boat had a meshi morai, so there were probably seven or eight of us. I’d go into the shed and there’d be others, so I had someone to play with and wasn’t bored.

The thing that caused the most trouble for the fishermen was the harbor. Countless big rocks along the shore left no place to moor a boat. The inlet at Old Azamo was large and could have made for a good harbor, but there were only a few of us, and it was just too hard for us to clear, so we decided to use Little Azamo, and set to clearing a harbor there.

Clearing a harbor meant removing the rocks that were lying around in it. People are resourceful, and after some thought the fishermen came up with a way to clear out the big rocks: When the tide was out and the sea was shallow, they’d put a boat on either side of a rock. Then they’d lay down a log across the two boats, and the strong fellows among them would dive into the water with a large rope made of wisteria vines and wrap it around the rock. And last, they’d tie the other end of the rope to the log which they’d slung between the boats. When the tide came in, the boats would rise and the rock too would float free, suspended in the ocean. Then they’d row their boats out and drop the rock in a deep spot. Using two boats and one turn of the tide, they could only move one rock. But working patiently, they managed to make a place where the boats could moor. All of us celebrated when the work was done but then a big storm came, bringing the rocks up with it again and making a mess of the harbor.

The fishermen had dumped the rocks in a bad place and it was decided they had to take them much farther out. And so they did. That was no ordinary effort. As a child, all I could do was watch, but in my own childish way I was impressed by how hard they worked. And you know, they did all of that between fishing runs.

In that way, the New Year passed and about the time the trees were coming into leaf we returned to Kuka. Back there, I was once again in Masamura’s keep and, as before, I helped out with the making of confections at my grandmother’s house. Then, when fall came, I came to Tsushima as a meshi morai. I repeated this until I turned ten, and since somehow or other I’d learned how to prepare meals, after that I went along as the cook. This work was for children who had yet to come of age, or for men who were over sixty. You’d eat what you were given and the pay was scanty, but poor families would send their children from early on to be cooks on fishing boats so that they’d have fewer mouths to feed.

By that time, I’d come to understand most of what was going on around me. It would have been fine to be a confectioner in Kuka, but since I had very few kin and could do whatever I wanted, wherever I wanted, I decided on the life of a fisherman and set out in earnest to learn how to fish.

After that, Azamo became more and more civilized. Everyone had a saw and hoe and they cut down trees and turned the soil. They cleared small plots and took to growing vegetables, and somehow made this place livable.

In only five or six years, between 1876 and 1882, Azamo changed beyond recognition. And while I’d thought of it as a very distant place, around that time boats were made stronger and their sails bigger, so they could go from Kuka to Tsushima in five or six days. Azamo became a place you could go to easily, in no time at all, as if you were going next door. And that happened with only a few small changes in the way boats were made. On top of that, in Azamo, though they were only sheds, we had homes. The more crude among them had knotty log posts and walls made from the branches of chinquapin trees, but when we came in from the sea at night, we had a place to sleep.

We weren’t educated. We didn’t know how to read or write and could hardly count money. We knew nothing of how they were keeping the accounts at the Kameya storehouse, and we asked Master Kameya to make Masamura Kunihira of Kuka the clerk there. Do you know of Kunihira? He was a great man. In Kuka, he could have lived with his hands in his pockets. After all, he was a gentleman. But he came to this remote place and became the storehouse clerk. The storehouse may have been Master Kameya’s, but being a man of understanding, he employed Kunihira. And we worked and left everything up to Kunihira.

Kunihira told us, “This storehouse should be owned by someone from Kuka. Things aren’t going well these days because Kameya doesn’t know how to do business. Living in Tsushima, he doesn’t understand the outside world, so he’s losing out all the time. It’s not like in the days of the feudal lords. People these days are shrewd, and nothing will come of this business if it’s handled in Kameya’s large-hearted manner. We must bring someone competent from Kuka to handle the business here. I can look after things, but I have work to do in Kuka, so I can’t devote all my energies to this place.” It was agreed that what Kunihira had said was quite reasonable and so Goshima Shinsuke was brought here to replace him. This guy came along and gave a kind of structure to Azamo. He was a deep thinker too and he said, “No doubt, in the future, things will open up as far as Korea. When that happens, Azamo will be right in the middle between Korea and Japan. All the fishing boats going to Korea will pass through here. To prepare for that time, we must all settle here. Nothing will come of going back to Kuka whenever winter comes. Those who can bring their parents and siblings should do so.” And saying this, he built himself a house with dirt walls.

Eventually everyone built houses. I was still young, so I was going back and forth between Kuka and Azamo, and in those days it was popular to leave Kuka for Hawaii. While a day of work in Kuka only paid thirteen sen [100 sen = 1 yen], in Hawaii you’d get fifty. Saying they wanted better earnings, people left, one after the other. But I was now a fisherman and had decided to spend my life catching fish, so I didn’t change my mind. And besides, I was catching a lot of fish. Try catching 150–250 pounds of sea bream in a day. Your fingers and arms start to hurt. They’re all big fish. You feel one on your line and try pulling, but it doesn’t come up. Just when you think you’ve snagged a rock, the fish starts jerking on the line. It’s no easy task to handle and humor it, and pull it up to the side of the boat. It’s like persuading a woman who hates you. You try this trick and that, letting the line out and pulling it in, and if you’re not careful, the line will be cut. On the other hand, there’s no greater happiness than when you bring one up. Try catching ten such sea bream in a single day. You’ll generally feel pretty good, and at night you’ll want to have a drink. At times like that, you don’t think about things like making money. I just felt that fishing was fascinating. It was a mystery to me why everyone in the world wouldn’t want to become a fisherman.

You know, it’s not like catching little sea bream off the coast of Kuka. Before long we weren’t just fishing at Ose. Twelve to fifteen miles farther out was another shoal, and we discovered lots of sea bream there too. I couldn’t believe my eyes. And it wasn’t just sea bream. We found an incredible number of swordfish—lots of big ones swimming with their fins up out of the water. But we didn’t know how to catch them, and we talked it over, saying “If we caught these, who knows how much money we’d make.”

There were lots of yellowtail, too. But Kuka fishermen specialized in sea bream, so we didn’t know how to catch yellowtail. If only someone could come and catch them. The whole situation was really frustrating.

Then, when I was coming back from Kuka, I met some fishermen from Okikamuro (in the Towa Township, Oshima District, Yamaguchi Prefecture) in Hakata. I asked them, “Do you want to try going to Tsushima? There are fabulously large fish. You catch them, and you catch them, but there are more than you can catch.”

“Are there yellowtail?” they asked.

“You want yellowtail? I said. “If you went to Tsushima you’d be amazed. When the yellowtail come, there are so many that the water level rises.”

“Is that true?”

“Would I lie?”

So it came to be that fishermen from Okikamuro came to Tsushima. That was 1887, and I’d become a competent young man. Those guys from Okikamuro knew how to fish yellowtail, and they came here and caught an appalling amount. They needed a storehouse, so they got Kuranari of Izuhara to be their wholesaler. He was a good man and treated them well. The yellowtail fishing spot was off Teppo Point, but they worked out of Azamo and developed Naka Azamo.

Just as it had been in Little Azamo, it was hard work clearing rocks out of the inlet, but by that time people knew how to get dynamite and break up the rocks with it. More fishing boats were also coming to these parts, and they made sure that each boat that came into the harbor slung a rock onboard and took it offshore, so clearing the harbor was easier than it had been in Little Azamo. Once the rocks had been cleared away, the harbor in Naka Azamo was larger and deeper, a good port.

You can’t build a harbor all at once, and though I said it was easier, it probably took about thirty years for it to get like it is now. A harbor that only held four or five boats when the fishermen from Okikamuro first came sheltered more than five hundred by the middle of the 1920s, and larger boats were able to come in too. You know, the energy and drive that fishermen have shouldn’t be taken lightly.

Azamo, Tsushima, Nagasaki Prefecture.

July 1950.

Up until late in the 1890s most of the homes in Azamo were sheds. They were truly crude. Then, in the same year that there was a war, in 1894 or 1895 [the years of the Sino-Japanese war], a big wind blew. I’d never seen a wind like that. Little Azamo is in a hollow so it wasn’t hit so bad, but in Naka Azamo the wind was channeled right in, and a lot of houses were blown over. I heard tell of a family who was sitting by their hearth when a huge gust suddenly came, picked their house up, and carried it eight to ten yards. The house was flattened. It’s said that the family suddenly realized they were sitting outdoors. That’s just how bad the typhoon was.

Well, things couldn’t go on like that. Typhoons would come again in the future, and stronger homes had to be built. There’s a place called Sare, near Okikamuro, and we brought a tile maker from there and had him make roof tiles. While there were stone roofs in other parts of Tsushima, this was the only place with tile roofs from early on. Tsushima was known for its hawks, crows, and stone roofs, but only here in Azamo we had tile roofs and plaster walls and rows of nice homes. People came from Tsutsu to have a look.

People really started to settle here late in the 1880s. In those days one could often see fox fire burning over on the other side of the inlet. It was rather unsettling. And on a really quiet night, there was sometimes a sound like the world being torn apart. People said this was probably Priest Tendo taking flight. By the late 1890s, the number of houses had grown to a hundred, and about seventy boats came from the Kii Domain to fish yellowtail every year. The harbor became lively, and we stopped seeing the fox fire or hearing the sound of Priest Tendo in flight. It seems that in this world we live in, people are at the top.

Around that time I got married and decided to live out my life here, and because we couldn’t get by on fishing alone, I taught my wife what I’d learned as a boy about how to make sweets. I’d go out to sea while my wife made sweets at home and sold them. In that way, we made a humble living.

There was a lot that was interesting and much that was sad. But as a person with no talents, fishing was about all that interested me. As for what was sad, the time when my wife suffered a loss was about all. Fifty years living with her, that was the happiest thing of all.

I’ve been talking for quite a while. Shall we take a break?