Читать книгу The Forgotten Japanese - Tsuneichi Miyamoto - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Translator’s Introduction

ОглавлениеMiyamoto Tsuneichi (1907–81) is one of Japan’s greatest ethnologists and one of her best kept secrets. Over a period of thirty years, Miyamoto walked some one hundred thousand miles in search of the meaning of life in rural Japan. He found it in the songs and stories, in the living and working habits of its fishermen, farmers, and mountain men and women. Born into a farming family on an island in Japan’s Inland Sea, Miyamoto was first a folklorist, an observer, and recorder who wrote more than eighty books and took ninety-five thousand photographs. But he did not stop there. He took what he had learned on the road and became a key government advisor, an advocate for the social and economic invigoration of rural communities weakened by outmigration and encumbered with an aging population.

Miyamoto’s parents were unable to pay for his education beyond junior high school, so after a year farming at home he set out to look for work in Osaka. Miyamoto was sixteen when his father sent him off with advice that would greatly influence his approach to life and to his work as an ethnographer:

1 When you take a train, look out the window at the condition of the fields and crops, the size of the homes, the kind of roofs they have. When you arrive at a station, watch carefully to see who is getting on or off. Observe their clothing and luggage. From this you will know if the place is wealthy or poor, whether it is a place where people work hard or not.

2 When you visit a city or town for the first time, always climb up someplace high to see where you are. Look for temples and for the forests that grow on shrine grounds. Look too at the nature of the homes and fields, and the surrounding mountains. If something at the top of a mountain catches your eye, go to it. If you take a good look from above, you will almost never lose your way.

3 If you have any money, try the local food and you will know the nature of life there.

4 If you have time, walk as much as you can. You will learn many things.

5 It’s not difficult to make money, but it’s hard to spend it wisely. Don’t forget that.

6 I’m unable to provide for your education, so I ask nothing of you. Do as you like, but take care of yourself. Think of yourself as disowned until you reach thirty, but thereafter, remember your parents.

7 If you become sick or have troubles you cannot resolve alone, then come back home. We will always be waiting for you.

8 This is no longer an age in which children care for their parents. It’s an age when parents care for their children. Otherwise the world will not improve.

9 Whatever you think is good, give it a try. We will not criticize your failures.

10 Look at what others have missed. There’s always something important to be found. There’s no need to rush. Whatever road you choose in life, walk it with purpose.

In Osaka, after working for the post office for several years and putting himself through teacher’s college, Miyamoto took a job as an elementary school teacher. When time permitted, he explored the countryside outside Osaka and began asking people about their lives. At twenty-two, Miyamoto came down with tuberculosis and returned home to Oshima Island to convalesce, but two years later he was back in Osaka, teaching elementary school and researching rural life.

In 1935, when Miyamoto was twenty-eight, he met Shibusawa Keizo, grandson of Shibusawa Eiichi, one of Japan’s most successful entrepreneurs. Ten years Miyamoto’s senior, Shibusawa was a banker and an avid ethnologist devoted to the study of the common people and their contributions to Japanese culture. He established the “Attic Museum” in a building on his own private property in Tokyo, which became a gathering place for Japanese tools and folk crafts, and for the young ethnologists whom Shibusawa engaged—and generously sponsored—in a wide variety of research efforts.

In 1939, at age thirty-two, Miyamoto resigned his job as an elementary school teacher and began walking and researching full time. With Shibusawa’s untiring encouragement and financial support, and often on government or academic assignment, Miyamoto would walk, look, and listen for much of the remainder of his life. In 1941 he went to Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, and heard stories that would become the basis for “Tosa Genji” and “Tosa Terakawa Night Tale” herein. Physically unfit to fight in the war, Miyamoto performed research for the government with regard to farm productivity and land reform. The war intensified around him and when Osaka was bombed in July, 1945, Miyamoto lost all of his research notes.

Having studied the resettlement of communities that had been devastated by landslides and flooding late in the nineteenth century—described in “Totsukawa Landslide” and “New Totsukawa”—Miyamoto helped communities that had been destroyed in the war resettle to Hokkaido. As an agricultural advisor to the Japanese government and later as a member of various interdisciplinary research teams, Miyamoto continued to explore and study villages that fished, farmed, and lumbered for their livelihood. In the early 1950s he began his first serious study of Japan’s islands, work that would contribute to the establishment of the Remote Island Development Act and to his becoming the first director of the Remote Island Development Council in 1953. His related travels to the island of Tsushima in 1950 and repeatedly thereafter would inform his writings in the first three chapters of this book.

Despite the return of tuberculosis in 1953, Miyamoto turned his incomparable energy to the study of forestry, visiting more than two hundred mountain communities in the mid- to late 1950s. The more he traveled, the more Miyamoto learned about fishing, farming, hunting, and logging, and about the ways in which individuals and communities fail, survive, and sometimes thrive.

Miyamoto encouraged rural communities to develop and sell products that were uniquely their own as a means of financial survival. On the island of Sado, for example, he advised farmers to grow a variety of persimmon that was unique to the area, and persimmons remain an important cash crop to this day. A persimmon farmer on Sado Island was known to have said, “Miyamoto gave us this factory, this port, and more importantly, he gave us pride in our lives.” Such examples can be found throughout Japan, in the thousands of villages Miyamoto visited as he walked the country. To this day there are monkey grinders, taiko drummers, countless museums of local culture, and local products that were spurred along and inspired by this man of rare energy and practical insight. And to this day, Sano Shinichi, Miyamoto’s primary biographer, continues to give talks about him; Miyamoto Tsuneichi reading groups read his books; and Sakamoto Nagatoshi tours with his monologue reenactment of “Tosa Genji.”

The Forgotten Japanese was first published in 1960. It is a collection of life stories and vignettes as told by men and women in their seventies, eighties, and nineties, people Miyamoto met during his research and travels. It is an eye-opener even for the Japanese; a look at life in rural Japan between 1850 and 1960 that introduces us to farmers, carpenters, and fortune-tellers who are adventurous, curious, mischievous, and resourceful. Through their lives we witness Japan’s modernization, and we are offered glimpses of important moments in her history as well.

These are the stories of common people; this is history and culture from the ground level. A carpenter is drafted to fight against the shogun’s army in a war that signals the end of the Tokugawa period. An old man describes the shogun’s final flight from Osaka, requisitioning a small boat to take him to safety. But the storyteller is as interested in the fate of the common boatman as in that of his famous passenger. We learn of families that are too poor to care for their own children and others who take them in, of outlandish priests, and of long and grueling hours of farm work. A woman tells of her travels to see the world. A woodsman talks of wolves, goblins, and fox spirits. A grandfather sings ballads to his grandson. When a boy is lost, the villagers go searching, knowing him well enough to suspect where he might have gone. We encounter a woman with leprosy on a narrow mountain path, and attend a village meeting that lasts through the night. We are introduced to fishermen, hunters, wood carvers, mountain ascetics; to people from every imaginable trade and livelihood. We witness men pulling carts, then horses pulling carts, and finally the arrival of paved roads and cars.

Vestiges of what Miyamoto found on his travels are still to be found in rural Japan to this day. While the bullet train has extended its reach into much of rural Japan and thatched roofs have been replaced by ceramic tiles, many rural Japanese continue to heat their baths with firewood, and individual communities hold meetings much like those Miyamoto experienced. The way of life that appeared to be nearing its end in Miyamoto’s time is still nearing its end today. It may finally disappear as the last of those born in the Meiji period pass away, their values and memories lost with them.

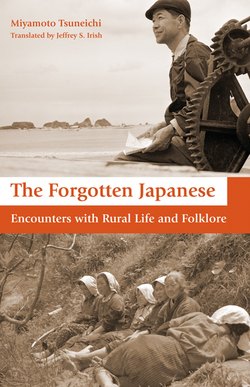

With the exception of the photographs in which Miyamoto appears, a photograph of Sakon Kumata in chapter 9 and a photograph of Tanaka Umeji in chapter 10, all photographs were taken by the author. Those that did not appear in the original Japanese version of The Forgotten Japanese were selected from among the ninety-five thousand photographs taken by Miyamoto with, for the most part, his Olympus Pen camera. The maps have been redrawn and expanded upon here to provide greater clarity and context. In an effort to make this compelling description of life in rural Japan all the more accessible, the chapter order has been changed slightly and the chapters have been arranged in two parts. In the first, we join Miyamoto on the road where we are introduced to his research methods and then offered accounts of individual lives, each a unique window on life in rural Japan. In the second, we step back to look at whole communities as they respond to a variety of crises and hardships. Only when the original text was redundant or where elaborate geographical details interrupted the flow of the writing have omissions been made. A glossary provides information regarding people, places, events, and concepts that may not be familiar to the reader.

In Japan, a younger person will often address someone older as “Grandpa,” “Grandma,” “Uncle,” or “Aunt,” though they are not related in any way. In the text that follows, Miyamoto often does this as well, out of affection and respect, and toward the establishment of a rapport that then led to the many frank and open conversations we find herein.

The Forgotten Japanese (original Japanese title: Wasurerareta Nihonjin) is now in its fifty-seventh printing in Japan. It has never been translated into English. This translation is based on a longer version of The Forgotten Japanese, prepared by the author as the tenth volume in a collection of his published works.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Miyamoto Tsuneichi’s eldest son, Chiharu, for his kind permission to translate his father’s work. I am also grateful to Messrs. Okamoto, Takasaki, and Takagi of the Suo oshima Cultural Exchange Center—where Miyamoto’s writings, photographs, and a vast collection of fishing, farming, and other tools are kept—for their assistance in the selection of photographs and in the checking of innumerable facts. Stewart Wachs, Jerry Irish, and Anne Connolly read, edited, and offered valuable advice with regard to the manuscript. Inagaki Naotomo, one of Miyamoto’s students, talked with me at length about his teacher while Sano Shinichi’s biography of and lectures regarding Miyamoto provided me with a new perspective on his life. Tsuda Yojiro of Iwanami Shoten generously shared important photographic data while Iwao Sudo and Haga Hideo allowed me to make use of their photographs of Miyamoto. Kikuno Kenichiro drew the maps and Kodama Tatsuro performed the map graphics. Nakamura Koji introduced me to the wonderful world of Miyamoto Tsuneichi, and Ken, John, and Stewart at the Kyoto Journal encouraged me to pursue this translation. The elderly members of my village served as a sounding board regarding life before the war, and Sayaka kept me going for the years that I disappeared into the vast world of this book and this man. Finally, I thank Peter Goodman of Stone Bridge Press who took on, and stuck with, this important story, helping it to find its way into the English language some fifty years after its Japanese debut.

Jeffrey S. Irish

Kagoshima Prefecture

Japan