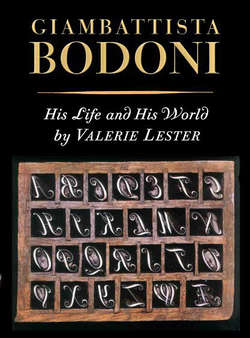

Читать книгу Giambattista Bodoni - Valerie Lester - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSaluzzo with Monviso in the background.

1

Saluzzo

PICTURE HIM! He is a vivacious child with wavy, light brown hair, and hazel eyes. Like other boys of his generation, he wears a long frock coat with large cuffs, breeches to the knee, stockings, and square-toed, buckled shoes. Diligent of hand and quick of wit, he soon reveals what the future holds for him. His toys are his grandfather’s punches and matrices, and under his father’s tutelage, he learns the rudiments of printing and takes to it with astonishing facility, often working with type when his schoolmates are at play. At school he rises to the top of the class and displays his passion for words, soon producing reams of prose and verse. He is well liked by his teachers and fellow students, many of whom grow up to be famous in their own right, in politics, the church, science, and academia. These fellow students have one particularly vivid memory of their childhood friend. During a religious festival with illuminations in Saluzzo, Giambattista created moving figures, representing scenes from the New Testament, on one of the exterior walls of his home.3

This early precursor to Italian moviemaking took place some time before his twelfth birthday, and is one of the few actual incidents on record from Bodoni’s childhood. However, a glance at his hometown, his family, the institutions and patterns of the age, (and the food he ate) go far to reveal the boy’s background and his destiny.

Saluzzo! Even the word sounds salutary, like a blessing for a sneeze. Bodoni’s birthplace is notched into a foothill of the Cottian Alps, close to Italy’s western border with France; its air is bracing and its view is wide. The cobbled streets rise sharply to the fourteenth-century castle that dominates the historic center, while lofty, snow-covered Monviso, which the Romans called Vesulus, lords it over the entire region. The house where Bodoni was born still stands at the start of a road now aptly named Via Bodoni, but the plaque on the front wall celebrating his life is today outshone by strident signs declaring “Lavasecco” and “Tintoria.” The ground floor is now a dry cleaning and dyeing establishment.

According to the register in Saluzzo’s Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta and San Chiaffredo (Saluzzo’s patron saint), Bodoni was born on 26 February 1740 and baptized Giovanni Battista by his uncle Carlo, a young priest. Dates of birth, so dear to the heart of biographers, are notoriously slippery. Even though Bodoni’s biographer, Giuseppe De Lama, presumably getting it straight from the horse’s widow’s mouth, holds firm for 16 February, the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani states firmly “Naque a Saluzzo il 26 (non il 16) febbr. 1740.”

The Bodoni family had moved to Saluzzo from Asti (of Asti Spumante fame) in the seventeenth century, and Bodoni himself tells this story about his grandfather, Gian Domenico:

. . . types were cut and cast in Saluzzo, in the workshop of my grandfather Gian Domenico Bodoni. When he was young, during the pontificate of Innocent XI [1676-89], he went to Rome and stayed there some years as a compositor in the Stamperia Camerale. He made friends with an engraver whose name I do not know, and learned punchcutting. When he returned home he spent his fortune and even sold a vineyard to support his passion for cutting punches and casting type. My father told me more than once that he had seen types being cast for a Garamone [sic] body, and I myself found a furnace set up on the gallery of our house, and moulds, counterpunches, a few punches and several matrices of little value.4 (See Appendices I, II and III for printing terms and an explanation of the printing process.)

Gian Domenico Bodoni married into a printing family when he wed Francesca Benedetta, the daughter of the printer Nicolà Valauri, an only child who inherited her father’s printing business. Unfortunately, Gian Domenico died in 1723 and the boy never had a chance to meet his grandfather in person; it would be a mistake, however, to underestimate the influence of being able to play with his grandfather’s printing equipment. The printing business was in turn inherited by Bodoni’s father, Francesco Agostino Bodoni, who improved and enlarged it. According to Stephan Füssel, Francesco Bodoni specialized in popular writings on cheap paper at affordable prices and “. . . all production stages were vertically integrated; not even the formes were bought from suppliers but were developed and cast in-house.”5 Bodoni’s mother, Paola Margarita Giolitti, came from a well-known family in Cavallermaggiore, about 80 miles from Saluzzo. She was said (perhaps wishfully) to have been descended from the famous Giolito family, illustrious Piedmontese printers of the sixteenth century who made their fortune in Venice and Monferrato.

Examples of printing by Bodoni’s grandfather (left) and father (right).

Giovanni Battista (whose name later became Giambattista) was the seventh child and fourth son of eleven children. Three died in infancy before his birth and one died shortly after, but he was robust and navigated the dangerous shoals of childhood with vigor, even though he was probably premature. His closest sibling in age, Angela Maria Rosalia, was born and died in May 1739; Bodoni arrived in the following February, a mere nine months later.6

Millennia before the Bodonis lived and died there, Saluzzo was a tribal city-state, inhabited by the mountain tribes of the Vagienni and the Salluvii. The Vagienni proved to be an irritant to Rome and were summarily annihilated in the third century B.C. As for the Salluvii, when they descended from the Alps and floated down the Durance to prey on Marseilles around 125 B.C., the Roman consul, Marcus Fulvius Flaccus, retaliated by marching into Saluzzo and taking control. At that point the Salluvii vanished into the mists of history, leaving nothing behind but a wisp of memory that survives in the word Saluzzo.

After the fall of Rome and the Dark Ages, Saluzzo became the site of territorial tugs-of-war, but during the relatively settled era of the marquisates from 1142 to 1548, the town burst into flower. Its altitude, good air, and abundance of food from nearby fertile plains provided a bulwark against decline. The marquises of Saluzzo left a legacy of impressive buildings, art, and chivalric romance. One of their most astonishing engineering feats, the first transalpine tunnel, was completed in 1481 during the marquisate of Ludovico II. This tunnel, affectionately known as Buco di Viso [Viso’s Hole], is 75 meters long, 2.5 meters wide, and 2 meters high; it burrows under Monviso at 2,882 meters above sea level and links Italy with France. The tunnel provided a necessary and effective trade route for the transportation of salt from Provence, as well as fabric, furniture, horses, and other livestock. In return, Italy exported rice, wool, and leather to France.7 By the middle of the eighteenth century, the tunnel had suffered many internal rock falls, so it is unlikely that the young Bodoni or his friends ever made the journey through it. Since then the tunnel has been repeatedly cleared and reopened.

Monviso, at 3,841 meters, is the highest mountain in the Cottian Alps. It is the site of the three sources of the Po, a river that persistently seeks out the East, rising near Italy’s border with France, flowing past Saluzzo and then across the entire north of Italy, finally mouthing its way into the Adriatic south of Venice.

In the late fourteenth century, the Marquis Tommaso III propelled Saluzzo onto the world scene with Le Chevalier Errant, his rambling, allegorical, chivalric “novel,” written in French, in both prose and poetry, and full of fables, legends, and peculiar science. It traces the travels and adventures of a dissolute but, of course, ultimately redeemed knight, and the concomitant dangers of earthly love. As contemporary portraits attest, the tale spawned generations of boys who rushed around on hobbyhorses, waving wooden swords.

Saluzzo and its lovely surroundings had already provided the scene for other literary adventures. Virgil mentions Vesulus (Monviso) in the Aeneid (X, 708). In the Decameron, Boccaccio tells the tale of cruel Gualtieri, marquis of Saluzzo, and his lovely wife, the infinitely patient Griselda. Petrarch tells the same tale in his De obedientia ac fide uxoria mythologia and his prohemium begins “Est ad Italiae latus occidum Vesulus, ex Apennini iugis mons unus altissimus.” [Vesulus/Monviso on the western side of Italy is the single highest mountain in the range of the Apennines.] Petrarch attracts Chaucer, who repeats the tale of the marquis of Saluzzo, now Walter, and patient Griselda almost word for translated word in “The Clerk’s Tale.” Here is Chaucer’s lovely description of Saluzzo (Saluces):

Ther is, right at the west syde of Ytaille,

Doun at the roote of Vesulus the colde

A lusty playn, habundant of vitaille,

Where many a tour and toun thou mayst biholde,

That founded were in tyme of fadres olde,

And many another delitable sighte,

And Saluces this noble contree highte.

The Clerk’s Tale, 57-63

These lines breed speculation: might Chaucer have visited Saluzzo when he traveled to Genoa and Florence in 1373?

Bodoni called Saluzzo his sweetest, most venerated birthplace, and retained a constant affection for it throughout his life. The beauty of the landscape, the literary and artistic tradition, and the opportunity to start printing at a very early age indelibly influenced the child who would become the greatest Italian printer of his era, and arguably of all time. This then was Bodoni’s patrimony: a small but important town set strategically on the top of a hill, on a trade route between France and Italy; an extravagantly fertile plain below; towering, gorgeous Monviso, one of the most perfectly shaped mountains in the world; a castle; beautiful civic and private buildings, some with terraces and exterior frescoes, including one of a particularly elegant Lady Geometry wielding an enormous pair of compasses; the hangover from chivalric romance; literary respect for patient women; and, most importantly, an already thriving printing tradition in which his own family played a major part.

IN 1729, the much-titled Vittorio Amedeo II (duke of Savoy, marquis of Saluzzo, marquis of Monferrato, prince of Piedmont, count of Aosta, Moriana and Nizza, king of Sicily, king of Sardinia) issued new legislative orders to his realm concerning education. The Comune of Saluzzo was directed to locate a bright and well-illuminated house with at least five rooms to act as classrooms. The Comune chose to rent the house of Signor Cavassa, heir of a powerful Renaissance family. The Casa Cavassa was built in the fifteenth century, carved and frescoed, and accommodated the steep nature of its site by flowing down six floors. The school, operated by the Jesuits and known as the Collegio Regio, was attended by Giambattista Bodoni and his brothers. In no way a backwater establishment, it attracted famous teachers from other parts of the country.

The Casa Cavassa, where Bodoni went to school.

The school year ran from November to August or September, at which point students were required to help with the harvest. No lessons were held on Thursdays and Sundays. The bell of the civic tower rang out each school morning to announce the start of lessons, a bell that served the useful purpose of informing parents of the time and thus preventing the boys (no girls, of course) from leaving home too early and making a nuisance of themselves in the town before classes. They attended Mass at school, and each morning recited a Latin prayer in unison, giving thanks to God, requesting help from the Blessed Virgin, and invoking protection for the sovereign. During holidays, they were obliged to attend Mass in their own parish.

The legislation of 1729 had ironclad rules: students were prohibited from playing ball; from frequenting cafés, inns, and theaters; from bearing firearms and knives; and from going to balls and wearing masks. Boys who failed to respect teachers and parents were harshly punished, and those who were incompetent or irreligious faced expulsion. These regulations were instituted deliberately to help to ensure the power of Savoy, and the sovereign, expecting complete obedience, left nothing to chance. Teachers were advised what classes to include; what textbooks to adopt; how to organize the school’s timetable; the way in which to correct and comment; the criteria for promoting boys from one class to the next; and the number of students per class. The regulations even went so far as to decree what homework the boys were assigned.8

A student was given seven years of education, but did not attend the actual school during his first year, working instead with tutors to learn how to read and write. Once installed at school, he began the study of Latin, Greek, Italian and French. Because of Saluzzo’s proximity to the French border, Bodoni grew up speaking Italian and French as well as the local dialect, which was seeded with both languages. Later, mathematics, history, geography, and mythology were introduced, and finally rhetoric, science, and humanities.

Bodoni’s sisters were taught to cook, mend, knit, and spin, and as members of the bourgeoisie, they could count on private tutors to teach them to “calculate” for the purpose of doing household accounts, and to read and write, as attested to by the letter of 22 September 1801 with its firm handwriting that Bodoni received from his sister Benedeta, saying “I have already written to you regarding the marriage that my son Francesco wants to make, without our consent . . . and your sister Angela has written to you . . .”9

Daughters of the nobility received a higher level of education. After learning to read and write, they studied French, the language of the court, reading mostly books of devotion and moral tales. They were taught to play a musical instrument, to draw, to paint, and to embroider. Poor girls were out of luck. Their job was working in the home; their challenge was to learn by example.

When the Comune first acquired the Casa Cavassa, the students and teachers endured long school hours in an unheated building with high ceilings and soaring windows, a building that threatened to collapse. The archives of the Comune contain a note of expenses for the acquisition of paper, flour, and oil for “breading” in the winter months. Breading refers to an early attempt at insulation in which paper imbued with oil and flour was placed over windows. Fortunately, in 1742, about five years before Bodoni entered the school, inspectors perceived the sorry state of the building and instituted desperately needed but minimal repairs.

The Casa Cavassa still stands, and functions as Saluzzo’s delightful municipal museum. It underwent serious restoration in the nineteenth century, and visitors today can enjoy its fifteen rooms, its frescoed chamber, Hans Klemer’s10 grisaille frescoes in the inner courtyard, painted wooden ceilings, period furniture, and the thought of young Giambattista Bodoni honing his already sharp intelligence within its walls.

As well as the influence of his family and his teachers, Bodoni was subject to the influence of the ruler of Savoy, in this case the long-lived Vittorio Amedeo III, a ruler known for his military courage, honesty, hard work, and wisdom. Giambattista grew up conservatively, respecting his ruler, his teachers, the church, and his family. He profited from a fine education in a small town where printing was already well established, and he lived in beautiful surroundings. With such a childhood behind him, he became a confident, ambitious young man, unafraid to seek fame and to boldly look it in the face.

Although no portraits exist of Bodoni as a boy, those that appear after his arrival in Parma reveal a handsome man who steadily gains girth as he grows older. He clearly relished his food; perhaps he enjoyed it too much, as gout would later suggest. One thing is certain: the food on offer in Saluzzo in his early years was of the highest quality, reflecting the cosmopolitan nature of the place.

Il cuoco piemontese perfezionato a Parigi11 is a marvelous book, published in Turin in 1766, and giving an idea of the kind of food available to the growing Bodoni family. Its anonymous author (most likely a man) follows the order of the seasons, starting with spring, which he calls the most pleasant season of all, but sadly lacking in chicks and ducklings, small birds, vegetables, and fruit. However, young hares and rabbits, piglets, lambs, calves, and kids abound, and fortunately beef has no season. Nor do eels or frogs. (Frog fricassée is a featured recipe.) Freshwater and saltwater fish are available. Artichokes, asparagus, certain kinds of mushrooms, peas, cardoons, spinach, lettuce, turnip tops, sorrel, and chervil come into season, as do strawberries, gooseberries, and cherries.

Summer sees an increase in poultry, game, and other birds, including songbirds. Beans, cauliflower, cabbage, and onions appear, along with peaches, plums, apricots, figs, currants, mulberries, melons, and pears. Autumn brings a bounty of fish, meat, cool weather vegetables and fruit, with the welcome addition of nuts, olives, and a huge variety of grapes. The lean winter months of December, January, and February, see an increase in the consumption of dairy products and dried and preserved food.

Even in 1766 Italians were already preoccupied with the preparation of coffee. The author insists that the beans be fresh and not vitiated by seawater (presumably on their perilous voyage from the Levant), should not smell moldy, and should be freshly ground. An ounce and a half of coffee per pint of water was the correct proportion, and if served with milk, that liquid had to be steaming before being poured on top of the coffee. How tempting, but forbidden, the local cafés must have been for the young Bodoni, and how delightful to celebrate the last of his schooldays by heading out to a previously forbidden café to celebrate with friends.

Yes, good food was certainly available for the growing boy. Wine, too. The area around Saluzzo was, and still is, rich in a variety of autochthonous vines, and is nowadays a center for the preservation of these ancient varietals. One light, sweet wine, pellaverga, was very popular in Bodoni’s day and has an interesting history. Every year, one of the marchionesses of Saluzzo, Margherita di Foix, would send thirty bottles to Pope Julius II, who appreciated the wine so much that in 1511 he made Saluzzo an episcopal seat.

Religion also played its customary part in the life of the Bodoni family, and Saluzzo’s dashing patron saint, the aforementioned San Chiaffredo, loomed large in the children’s lives. He was easy enough for them to recognize because of his attributes of sword, standard, elm, and military attire. His handsome portrait by Hans Klemer hung in the cathedral, and his shrine in nearby Crissolo attracted pilgrims in search of miracles. Legend has him born in Egypt and a soldier in the famous Theban legion, most of whose members were Christian. In 285 A.D., the co-emperors Maximian and Diocletian, wanting to quell a revolt in Gaul, shipped the entire Theban legion, 6,600 strong, from Egypt to Rome, and then marched it north through Italy and over the Saint Bernard pass into Switzerland. After successfully crushing the revolt, the soldiers camped in nearby Agaunum (now the Swiss town of St. Maurice-en-Valais) and were ordered to celebrate their victory with sacrifices to the Roman gods. To a man, the Theban legion refused, whereupon they were decimated (that is, a tenth of them was slaughtered). When the remaining troops still refused to comply, another tenth was slaughtered, and so on. Chiaffredo escaped. He made his way back over the Alps, finally reaching Crissolo, about 30 kilometers due west of Saluzzo, where he met eventual martyrdom.

In about 522, a man fell over a precipice near Crissolo and landed miraculously unhurt. The local populace attributed the miracle to his having fallen on the very spot where a skeleton had been plowed up by a peasant, its bones attributed to San Chiaffredo. The cult of San Chiaffredo is still very much alive today, and the sanctuary in Crissolo contains his relics and a vast number of votive offerings.

AT SOME TIME during Bodoni’s teenage years, just when he was finishing his course in “philosophic studies,”12 his brother Nicolino died. Nicolino, nine years older than Giambattista, had shown enormous promise. Not only had he taken holy orders, but he had become a doctor of law, on top of which he received high honors in the public examination at the University of Turin. These achievements opened the door to his becoming tutor to the children of the marquis of San Germano. His death occurred just a year after he entered the marquis’s household.

Giambattista, until then committed to the study of philosophy, immediately changed his mind in favor of following his brother into the Church. This plan was summarily scotched by the bishop of Saluzzo, who was well aware of Bodoni’s overwhelming liveliness [la soverchia sua vivacità13]. After talking things over with the bishop, the youth decided to enter his father’s business and train as a printer, a natural decision considering his early prowess. He also showed exceptional skill making wood engravings, often using San Chiaffredo as his subject. Everyone, but in particular the bishop, was astonished by the ease with which he accomplished his designs and how quickly he achieved results. Giambattista, too, was well satisfied with his work and, always ambitious, decided he needed a wider market than Saluzzo. Off he went to Turin, where his prints found ready buyers. He stayed for a while in that city, pleasing his father by furthering his education under the guidance of the printer Francesco Antonio Maiaresse.

Ambition had taken hold of him. Turin was all very well, but Rome would offer him greater opportunities for glory — glory for himself, for his family, for Saluzzo, for Italy. Hadn’t grandfather Gian Domenico already paved the way? Bodoni returned to Saluzzo to make preparations for travel to Rome, determined to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps. The bishop endorsed his plan and encouraged him to acquire training in engraving while he was there, recommending that he seek instruction from the engraver Lucchesini.

As a traveling companion, Giambattista chose his friend Ignazio Cappa, a discerning and capable young man who had also worked with his own father, a specialist in wrought iron. Bodoni beguiled him into joining the adventure, but just before they were ready to leave, Cappa lost his nerve. This did not deter Bodoni. He quickly assessed the rest of his comrades, and his eye lit on Domenico Costa, a young man destined for the Church, for whom the idea of Rome had a strong attraction. Costa turned out to be a better choice than the anxious Cappa, being filled with a soaring ambition that more than matched Bodoni’s. While Bodoni intended to become the pride and joy of all Italy, Costa saw himself as an exemplary shepherd of souls and the pride and joy of God. Both came from that breed of Piemontese whom their fellow Italians described as tough and self-reliant, and both certainly lived up to this reputation.

The young men raised money for their journey however they could. Bodoni went into a frenzy of wood engraving and printing, producing a series of vignettes and decorations to sell when they arrived in Rome. He and Cappa were breezily confident about finding accommodation with family members. Costa had an uncle who was secretary to Abbot Lagnasco, the Polish ambassador to the Pontificate, and Bodoni counted on his uncle Carlo, then living in Rome, and the same priest who had baptized him.

Giambattista and Domenico chose to leave Saluzzo on Ash Wednesday, which in 1758 fell on 8 February.14 The day before, martedì grasso, the Bodoni family would have prepared an enormous farewell meal that would hold Bodoni over for a lean Lent, and they would also have made sure that his knapsack was stuffed with cheese, salted anchovies, and bread for the journey.

“Dopo aver asciugato coi loro baci le lacrime delle rispettive mamme . . .”15 [After having dried with their kisses the tears of their respective mammas], they said goodbye to the rest of their families. Giambattista embraced his brother Domenico, who would work for most of his life in the family printing business in Saluzzo; his sister Benedeta, just married to Angelo Lobetti (she was the only member of that generation of the Bodoni family to produce heirs); his brother, the mysterious Felice Vincenzo, about whom nothing is known; his sister, Angela; and Giuseppe, the brother who would work shoulder to shoulder with him in later years.

Then Bodoni and Costa turned their backs on Saluzzo. Giambattista was not yet eighteen years old.

IT IS ANNOYING not to know precisely by what means the boys traveled. The possibilities were: foot, horseback, diligence (a public stagecoach), and private coach, this last being extremely unlikely due to its cost. The most likely choice would be a local diligence to Turin before a long-distance diligence from Turin to Genoa, then a sailing vessel from Genoa to Civitavecchia, and another diligence from there to Rome. “Viaggio lungo, faticoso, interminabile”16 says Carlo Martini. Yes — long, exhausting, and seemingly interminable for two eager young men.

The entire journey lasted from at least eight days to as much as two or three weeks, depending on the length of their stay in Genoa and their means of transportation. The diligence from Turin to Genoa stopped overnight along the way, and passengers descended to eat their meal of the day and to stay in local establishments of varying degrees of sleaziness. On offer were inns, guesthouses, and rooms in private homes. Sometimes travelers were given dirty hay to sleep on, but this might have been preferable to the letto abitato, a bed shared with other people and bed bugs. Tobias Smollett, the dyspeptic Scottish author, traveling in Italy at almost the same time as Bodoni, grumbles: “The hostlers, postilions, and other fellows hanging about the post-houses in Italy, are the most greedy, impertinent, and provoking. Happy are those travelers who have phlegm enough to disregard their insolence and importunity: for this is not so disagreeable as their revenge is dangerous.”17 Invariably, travelers came away feeling exploited, and quickly learned to negotiate a price before agreeing to spend the night.

Lenten fare along the way would have consisted mainly of vegetable soup, which relied heavily on field greens and a variety of legumes such as kidney beans, chickpeas, lentils, and above all fava beans. Bread, omelets, anchovies, frogs, snails, crabs, plus fresh water fish caught in local ditches and streams, would also be available18 — for prices the boys may not have been able to afford.

At Genoa, Bodoni had his first sight of the sea; until then, his experience with important bodies of water had been exposure to a rather petite Po flowing through the lower reaches of Saluzzo and a plumper Po flowing through Turin. At Genoa, la Superba, with the Appenines at her back and the Mediterranean at her feet, Bodoni came into contact with a city filled with gorgeous palaces and parks plus all the seaminess of a port that was home to sailing vessels plying their trade from port to port in the Mediterranean.

Bodoni and Costa remained in Genoa waiting for transportation to take them south. Bodoni spent his time wisely: he quickly found work with a printer. (Genoa has a history of printing dating back as far as 1471.) There he earned more funds for the continuation of the journey. Finally, in the most likely scenario, he and Costa set sail for Civitavecchia, the port for Rome, rather than traveling overland.

On arrival at Civitavecchia, after a fast, stomach-churning winter sail, with the north wind racing down the coast of Italy, they would pick up a diligence for the last stage of their journey of 85 kilometers along the Via Aurelia to Rome. The closer they approached Rome, the more desolate the landscape became, a landscape exhausted by its own glorious past, now nothing more than an unproductive wasteland. After the sweet orderliness of Saluzzo, the long approach to Rome through this miserable malarial wilderness would have been disconcerting and disappointing. At last the diligence passed through the Porta San Pancrazio and into Rome, near the top of the Janiculum hill.

Now we must imagine the moment: a few paces more and the boys can quench their thirst in the huge, gushing Acqua Paola fountain, and then, looking east, they see the city unfolding in the valley below. Look! There’s the Tiber! I see the Pantheon! Is that the Forum? Over there on that hill, that’s Trinità dei Monti! Look at the snowcapped mountains beyond!

They had arrived at last, and all Rome lay at their feet as they gazed out across the Tiber.

The Palazzo Valentini, Bodoni’s home in Rome, directly behind Trajan’s column.

PLATE 1 Don Ferdinando di Borbone, Duke of Parma. Circa 1770. By Pietro Melchiorre Ferrari.

PLATE 2 Father Paolo Maria Paciaudi. By Giuseppe Lucatelli.

PLATE 3 Ennemond Petitot. By Domenico Muzzi.

PLATE 4 Guillaume Du Tillot, Prime Minister of Parma. By Pietro Melchiorre Ferrari.

PLATE 5 Don Ferdinando di Borbone, Duke of Parma. By Johann Zoffany.

PLATE 6 Maria Amalia of Austria, Duchess of Parma. By Johann Zoffany.

PLATE 7 José Nicolás de Azara. By Anton Raphael Mengs.

PLATE 8 Joachin Murat, King of Naples.

PLATE 9 Is it or isn’t it Bodoni? This unnamed portrait of a young man, attributed variously to the artists Giuseppe Baldrighi and Andrea Appiani, was long assumed to be of Bodoni. Recently, experts in the history of clothing have dated it to the 1790s rather than the 1770s, so unless either artist were drawing from memory, it is probably not Bodoni. However, the young man’s features so closely resemble those in Appiani’s later portrait that a face-match on iPhoto paired the two images.

PLATE 10 Giambattista Bodoni. By Andrea Appiani.

PLATE 11 Napoleon in the Robes of the King of Italy. By Andrea Appiani.

PLATE 12 Empress Marie Louise of France. Later Duchess of Parma. By Robert Lefèvre.

PLATE 13 Don Ferdinando in Maturity. Artist unknown.

PLATE 14 Maria Amalia in Maturity. Artist unknown.

PLATE 15 Giambattista Bodoni in 1792. By Giuseppe Turchi.

PLATE 16 Giambattista Bodoni. By Giuseppe Lucatelli.

PLATE 17 Margherita Dall’Aglio Bodoni. By Giuseppe Bossi.

PLATE 18 Camera di San Paolo by Correggio.