Читать книгу Giambattista Bodoni - Valerie Lester - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

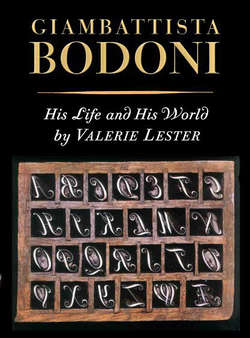

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

I HEARD the word Bodoni for the first time at a dinner party in California, over a meal of pork loin, roast potatoes, and asparagus. As we lingered over dessert, strawberries and crème fraîche, our host suddenly announced: “I recently had a call from a bookseller who told me I am the owner of a ‘hot’ book.” He shuddered painfully. “It’s the jewel of my collection, and I must return it to its rightful owner.”

I felt the sudden prickle of interest. I had been casting about for a new project, fooling around with this and that — articles, a translation, newsletters — but nothing major had grabbed my attention. Here’s an approximation of the conversation that ensued.

“What’s the book?” I asked.

“Bodoni’s Manuale tipografico, the sum, the summit, the chef d’oeuvre, the masterpiece, the work of all his works.”

“Who is Bodoni?”

“The illustrious Italian printer and type designer, born 1740, died 1813.”

“Why is the book ‘hot’?”

“I bought it from a dealer, who bought it from a dealer, who bought it from a dealer, who bought it at auction, where it had been put up by a ‘collector’ who had stolen it from a university’s rare book collection. It’s ‘hot’ not because it’s naughty; it’s hot because it’s swag.” A ripple of excitement shivered up my spine.

Bodoni, Italy, swag. I knew I had found my topic.

At first I was distracted by the theft of the book rather than by Bodoni himself, and I spent time wandering down that particular street of thieves. I importuned my husband Jim, a psychologist, to go to the Library of Congress to research book theft in general. The most salient fact he gathered was that book thieves were almost invariably men, with the occasional moll sitting quietly in the getaway car. But the convicted thief of the Manuale tipografico was a woman.1

Mimi Meyer worked as a volunteer in the book conservation department of the Harry Ransom Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. A short, smiling, self-effacing woman with brown hair, she blended in with her background like a nondescript little bird. She had free rein in the library, and she was often seen in the company of the Professional Librarian (who happened to be her romantic partner). Over a period of years during the 1980s and until 1992, Meyer stole literally hundreds of rare books. The choice of subject matter was eclectic; it included topics such as printing, horses, Oxford, and rowing. (Meyer and her partner were rowing enthusiasts.) Some volumes were clearly chosen for their value: a quarto edition of Audubon’s Birds of America; Japanese art books; works by Lewis Carroll; and, of course, Bodoni’s Manuale tipografico. Others were chosen because of the beauty of their bindings.

How did she manage these thefts, and on such a grand scale? She admitted that she stowed books under her clothes, but it is hard to imagine a small woman tucking Birds of America or the large, two-volume Manuale tipografico under her dress and getting away with it; it is easy to imagine, but impossible to prove, alternative scenarios.

Day by day, the collection grew, but one day she slipped up; she was found with a rare book outside the secure area. This was a flagrant transgression, and she was summarily dismissed. Although the librarians had already begun to notice the absence of certain books, the university was unable to prove her guilty of theft at that time.

Meyer guarded the books carefully, but eventually found herself in financial straits, so she put her conservation skills to use and started removing evidence of provenance, sometimes covering existing bookplates with other bookplates, sometimes even removing incriminating pages. She then sought out high-end dealers and auction houses, and over time became known as a serious collector who had inherited rare books from a relative. But eagle-eyed and educated dealers have long memories and are often well-acquainted with individual books, and the appearance in a Swann Galleries’ auction catalog of a rare Il Petrarcha caught the eye of such a dealer. He knew the book well — it was the beautiful vellum edition bound in red goatskin, containing Petrarch’s sonnets to Laura, published by Aldus Manutius in 1514 — and he knew where it belonged. He immediately reached out to the librarians at the University of Texas, who double-checked and found it missing. They in turn made contact with the FBI, who followed the trail to Meyer, and swooped.

Mimi Meyer confessed to her crime, and agreed to cooperate with the FBI. By this time, not only had she provided Swann Galleries with 46 volumes, but she had sold another 57 volumes through Sotheby’s in New York, Heritage Book Auctions in Los Angeles, and Pacific Book Auction Galleries in San Francisco, thus earning herself a tidy sum of money. The FBI catalogued another 781 stolen books still at her home.

On 30 January 2004, U.S. District Judge Sam Sparks issued Mimi Meyer a three-year probation and ordered her to pay $381,595 in restitution fees. She escaped a prison sentence because of her cooperation with the investigation and because she was then being treated for alcoholism and mental problems. Witnesses at her trial remarked that Meyer, then 57, was a small woman with surprisingly large red hands.

The good news is that, even though my host had to return his copy of Bodoni’s Manuale tipografico to the University of Texas, he was reimbursed the cost of the book through the State of Texas restitution fund. He was then able to locate another copy of the Manuale that he likes just as well as the first. So the jewel was in fact restored as the crown of his collection.

As for me, after that flurry of interest in book theft, I found myself more and more drawn to the robust Bodoni himself, to his career, his geography, and his cuisine. To my dismay, however, when I started trying to discover something, anything at all, about him, I learned that, while plenty had been written about him in Italian two hundred years ago and then again at the centennial of his death one hundred years ago, precious little apart from T.M. Cleland’s 1913 biographical essay had ever been written in English.2 What could I do? How could I learn more?

I did what any person totally out of her mind would do. I shook off my fascination with book thievery, brushed up my vestigial Italian, and set course for Italy, the eighteenth century, and the life and times of Giambattista Bodoni.

V.L.

SEPTEMBER 2014