Читать книгу Giambattista Bodoni - Valerie Lester - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLa Pilotta from the town.

4

Parma 1768

City of sweet, enveloping fogs and flat horizons marked by majestic poplars . . . city of masks and narcissistic poses, sophistication, epicurean appetites, and earthy realism . . . All in all, the city is gorgeous.

WALLIS WILDE-MENOZZI

PARMA in February is damp and cold. On some winter days, fog obscures the distant Apennines; sometimes it obscures the hand in front of your face. On other days, snow and ice turn cobbles into treacherous chutes. The city boasts an air of mystery and chilly grandeur that is swiftly dispelled by shafts of winter sun illuminating red and ochre buildings and the pink Verona marble of the baptistry. Unlike Saluzzo and Rome, Parma is flat, sitting on a bed of gravel 400 meters deep that helps absorb earthquakes. The city bestrides the Parma, a considerable river for most of the year as it snakes its way to join the Po, but which is referred to as a torrente rather than a river because of its ability to flood in autumn and dry up completely in summer.

A thriving center of printing as early as 1472, Parma produced a quantity of incunabula, that is, works printed in the 45 years following Gutenberg’s first use of a moveable type press in the 1450s. After this flowering, printing in Parma languished, in common with printing in much of the rest of Italy, apart from Turin and Venice. The Farnese family, rulers of Parma from 1545 until 1731, pursued large-scale, wide-ranging projects but had not the slightest interest in publishing books. Meanwhile, printing was flourishing in other European countries, especially in the cities of Paris, Madrid, Lyons, and Basel.

THE COACH bringing Bodoni to Parma arrived at noon on Saint Matthias’s day, 25 February 1768.78 (Usually falling on 24 February, St Matthias’s day was celebrated on the 25th in leap years like 1768.) The significance of this date would not have been lost on Bodoni; tradition held that it was the luckiest day of the year because Saint Matthias won the lottery to replace Judas Iscariot as Jesus’s twelfth apostle.

Bodoni’s first task was to find the site of the new printing office that, with his lodgings one floor above, was located in the palace of the Pilotta on the banks of the river. Prime Minister Du Tillot had informed him that this site would be temporary; he had grandiose plans for a state-of-the-art printing establishment on its own site, but the offices in the Pilotta turned out to be Bodoni’s workplace for the rest of his life.

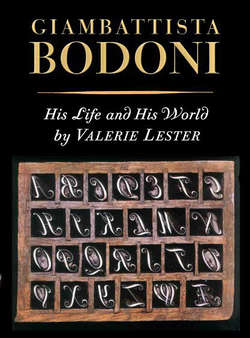

La Pilotta.

The palace of the Pilotta, a vast, forbidding complex, was built in 1583 by the Farnese family, who did not occupy it but used it as a setting for court and government affairs and theatrical extravaganzas. It housed the immense and staggeringly pretentious Farnese theatre and a smaller theatre for the court, as well as barracks, armory, stables, feed stores, and a playing ground for jeu de paume, the ancestor of handball and tennis. The scale of the Pilotta was so vast that it could accommodate all this and later house the Archaeological Museum, the Academy of Fine Arts, and the National Gallery.

Bodoni discovered the rooms that were to become his printing office on the ground floor of the west wing of the Pilotta, near where the Ponte della Rochetta (also called the Ponte Verde and now named the Ponte Verdi) crossed the river and led directly to the ducal park and palace. In days to come, if the river were in flood, Bodoni would occasionally find waves lapping at the doors of his studio. His living quarters boasted a fine view across the water to La Rochetta, the 13th-century tower on the other side and, beyond the tower, to the ducal gardens. In an otherwise closely built town, the open sky and spacious view across the water were a pleasant and welcome relief from the exacting, close work of publishing.

When Bodoni arrived, Father Paciaudi was in the process of establishing the library, now the Biblioteca Palatina, which was also housed inside the Pilotta. The happy reunion between Paciaudi, now a mature 58-year-old, and 28-year-old Bodoni was freighted with significance for both of them. Paciaudi was certainly taking a risk by bringing a virtually unknown Italian printer to Parma instead of a surefire Frenchman; Bodoni carried the burden of living up to the expectations of Paciaudi, of Prime Minister Du Tillot, and of the young duke, Don Ferdinando I (referred to as “Don” because King Philip V, the Bourbon king of Spain, was his grandfather, and he himself was an infante of Spain).

All three men — Paciaudi, Du Tillot, and Don Ferdinando — were relying on Bodoni to put Parma on the map, and it is worth getting to know them.

Father Paolo Maria Paciaudi was an extraordinarily erudite man with a passion for organizing. When Bodoni knew him in Rome, he was a fiery and fashionable preacher and an archaeologist. After years of excavating and cataloging in both Naples and Rome under the aegis of Cardinal Spinelli, he was invited to Parma in 1761 by Prime Minister Du Tillot. Together the two men worked for educational and ecclesiastical reform, and it was Du Tillot who gave Paciaudi the mandate to re-establish the city’s library. (Paciaudi was the first in Italy to use index cards as a means of cataloging books.) He would subsequently become the head librarian, antiquarian, and overseer of archaeological excavations at nearby Veleia.

More important for this story is that Paciaudi had never forgotten the skill of young Giambattista Bodoni at the Propaganda Fide in Rome. What had impressed him most was Bodoni’s talent for working with exotic languages. This was a gift that could add glamour to a newly established press.

LÉON GUILLAUME DU TILLOT was born in Bayonne in 1711. The son of a valet de chambre, and expected to follow in his father’s footsteps, he was a handsome whippet of a man with rapier-like intelligence who made his own way in life and was prepared to leave France if offered the opportunity for advancement. He found work in the household of Don Filippo, Don Ferdinando’s father, in Madrid, and accompanied him to Parma when Don Filippo became duke in 1749. Don Filippo quickly made Du Tillot minister of finance, which meant he was effectively in charge of everything. Henri Bédarida describes him as an egalitarian, although always loyal to the sovereigns he served, a man who desired order and regularity but had the ability to adapt, a man who was blessed with an elegant spirit, a happy physiognomy, and a slender silhouette.79

Du Tillot had unflagging inventiveness and energy, and he was determined to infuse the city with the spirit of French idealism. He was innovative; he encouraged business, trade, technological reforms, industrial arts, the manufacture of silk, and beekeeping. In 1753 he imported the French architect Ennemond-Alexandre Petitot and the sculptor Jean Baptiste Boudard to freshen Parma’s tired face. He was the power behind the reawakening of the University of Parma; he instituted museums and the Academy of Beaux Arts, and he was a religious reformer who made many enemies within the Church with his sweeping ecclesiastical reforms. These reforms included the closing of nonproductive convents and monasteries, and just before Bodoni’s arrival in Parma, Du Tillot influenced the duke to sign a decree banishing Jesuits from the city, and that decree was turned into action on 7 February 1768. Unfortunately, Du Tillot also made enemies among the local people, who resented his reforms and above all resented the imposition of so much Frenchification. He had surrounded himself with his compatriots, importing not only Petitot and Boudard but other French workers in place of Italians to take care of the needs of the court. Among these workers were carpet makers, mattress makers, tailors, corset makers, clock makers, carpenters, cabinet makers, metal workers, carriage makers, and gardeners.80

Du Tillot first realized the importance of having a press at his command when he wanted to publish a special book as a present for Don Filippo, but had to send it out of the country for publication. No press in Parma in those years was capable of printing a truly elegant book. He also needed a printing office where material could be produced secretly, engaged as he was in a mighty struggle with Rome over issues of ecclesiastical reform.

He set the wheels in motion for the instigation of the press by acquiring supplies of high quality paper and ink, and then he started hunting down good type. In 1758, on seeing a specimen page of Fournier’s type, he wrote eagerly about it to Anicet Melot in France. He commented on how beautifully proportioned and elegant Fournier’s designs were and wondered if it were possible to acquire some typefaces, including a few rare examples. Melot responded by sending characters “considered by experts to be the best ever made”81 and insisted that an intelligent compositor who could use them with good taste would produce superior work. That was the catch; skilled compositors were hard to find.

Years passed, and Du Tillot was promoted from finance minister to prime minister, granted the title of marchese di Felino [marquis of Felino], and given the lands that accompanied the title. He was often seen in company with the beautiful, literate, and highly intelligent Marchesa Anna Malaspina, the unofficial first lady of the court. Known affectionately as “Annetta,” she was the wife of Marchese Giovanni Malaspina della Bastia, a gentleman of the ducal household. She was also the close confidante and mistress of Du Tillot. Her beauty and charm were such that in earlier years she had been summoned to Versailles to distract King Louis XV’s attention from Madame de Pompadour. At Parma, “Fiorella Dianeja” (her Arcadian name) was adored by poets, soldiers, and the entire court. “But the prime minister himself was the man whom her beautiful eyes had conquered above all.”82

Du Tillot was alert to new developments and inventions. Smallpox was a terrible scourge in those days, and after the death of Don Filippo’s wife, Louise-Élizabeth of France, from the disease, Du Tillot encouraged the duke to bring Théodore Tronchin, the great Swiss physician and proponent of inoculation, to Parma to inoculate his son, the 13-year-old Ferdinando. It was a wise move; Ferdinando never succumbed to smallpox, but his father, who did not take advantage of Tronchin’s skill and Du Tillot’s advice, died of it in 1765.83 The death of Don Filippo and the young age of Don Ferdinando effectively meant that Du Tillot became the most powerful man in the duchy of Parma, Piacenza, and Guastalla. A prestigious court press was now not a whim but an absolute necessity.

In fact, three other presses were already operating in Parma, but they were all dedicated to specific utilitarian purposes. One printed material for the state and for the bishops of Parma and other towns; a second printed material for the mayor; and the third produced scientific and literary texts.84 None of them aspired to the heights of grandeur that Du Tillot envisioned for the royal press. Although advised by early planners that the printing office could operate perfectly well with just one press, a small selection of type, and a few decorations,85 Du Tillot was adamant; he wanted far more. But first he sought Paciaudi’s counsel in the matter of a perfect, available, intelligent, expert printer who could set up and then run the printing office. It was then that Paciaudi had the brilliant idea of suggesting Giambattista Bodoni.

At the time of Bodoni’s arrival in Parma in 1768, Don Ferdinando was 17 years old. On his mother’s side, he was the favorite grandson of Louis XV of France, and from an early age he had been educated by French tutors. One of these was Baron Auguste de Keralio, a mathematician and military engineer. Ferdinando himself described him as a truly honest, but excessively severe, man to whom was owed what little value he possessed. The other tutor was Abbé Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, a philosopher, proto-psychologist, sensualist,86 friend of Rousseau, and key figure in the French Enlightenment. Ferdinando was more interested in what Keralio had to teach him than what the philosopher Condillac espoused; speculation was never Ferdinando’s strength, while physics and mechanics remained of interest for the rest of his life.87 It may have been the young duke’s resistance to serious philosphical thought, and his own insistence upon it, that drove Condillac to write his 13-volume Cours d’Étude pour l’Instruction du Prince de Parme, which was finally published in its entirety by Bodoni in 1782.

Limp, lame, plump, and squat, the young Don Ferdinando was certainly unprepossessing. In the early 1770s, Lady Mary Coke described him as having “a very handsome face, fair complexion, fair hair, and dark eyes, good teeth, and something agreeable in his countenance, tho’ not a look of sense. His figure bad, very short and thick.”88 Joseph II of Austria described him as being well-mannered, inexperienced, but having no genius and little intelligence, and “is as tiresome as it is possible to be, leaning on my arm and never leaving me alone for a step.”89

Don Ferdinando spent a great deal of time praying ostentatiously. Marzio Dall’Acqua points out: “He was religious to the point of bigotry, careful to present an external faith, which manifested itself in rites, vestments, collections of relics, trips to various sanctuaries, especially Loretto. Yet his character was also joyful . . . He loved performing in the little theatre at the court in Colorno, and loved celebrating holidays with the countrywomen . . .”90 Generally regarded as pious to a fault, the purity of his piety has been questioned by some. People in Parma still gossip about him as though he were alive. Gossip, like rumor, knows no bounds; a few say he liked to dress up as a shepherd and head out into the countryside to round up not sheep, but pretty young women.91