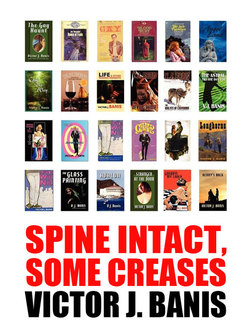

Читать книгу Spine Intact, Some Creases - Victor J. Banis - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

PAPERBACK VIRGIN

By the early sixties I had tried on a number of different hats. Acting, for one. I sang vowels over burning candles, the idea being not to make the flame flicker. I was pretty good at non-flickering but I was paralyzed by stage fright. Anyway, I was willowy and a bit effeminate. My drama coach kept the candles burning but warned me I had to be prepared to be limited to character parts. Later I would have welcomed that suggestion but at the time I thought he was insulting me. My real ambition was to play Lady Macbeth and I still believe I would have been fabulous in the part—but outside of Harvard there weren’t a lot of theater companies casting men in women’s parts in the fifties.

I moved on to dancing—I wasn’t bad for a guy with a questionable sense of rhythm. High on my list of Things-I-Never-Imagined is that time when I danced in Swan Lake with the La Scala Ballet Company.

Well, tee hee, that is a not-quite fib. I was only a super—a supernumerary, to be exact (or a spear carrier to make it clearer)—with the Company, and I had signed on mostly because the legendary Carla Fracci was dancing Odette and Odile.

What happened was, in the big wedding scene I was the friendly innkeeper and when I asked in rehearsal what we supers should do with ourselves, the director said, “It’s a wedding. What would you do at a wedding?”

I thought about it, and each night when the festivities began I grabbed my stage wife and we whirled around the big wedding table. So it’s not quite a fib to say I danced in Swan Lake with the La Scala Ballet Company, which is more than a lot of serious dance students can claim.

That, however, was pretty nearly the extent of my dancing career. I tried singing as well, with not much more success. I did get to appear with the San Francisco Opera Company but it was, again, only as a super. I met some fabulous people, including Placido Domingo, who couldn’t have been more charming. I had lots of fun but unfortunately this does not exactly constitute a career in music.

I made a stab at modeling. Somewhere out there surely copies remain of Army & Navy Times with yours truly in Navy blues (I’m afraid the white socks rather spoiled the illusion). Anyway, despite my best efforts—gazing into mirrors, glancing back at the camera from under my armpit—the shots they used avoided my face. A bad omen for any aspiring model, I fear.

Oddly enough, what I hadn’t pursued was writing. Oh, I still wrote, for my own pleasure. I was even published here and there. Some poetry in One magazine and a short story in Der Kreis, an early gay magazine published in Zürich (Switzerland) in three languages and also called Le Cercle and The Circle. In 1963 they announced an English-language short story competition, to which I submitted a gem titled “Broken Record,” which came in fourth and got me no prize, but was published. The magazine is long defunct, the story long out of print, and you are highly unlikely ever to see it anywhere—which is perhaps just as well.

“Broken Record” was not my only writing effort at the time. I worked for a while on a novel, Perry for President, in which a cartoonist launches a presidential campaign for his main character, Perry the Ostrich, and the campaign becomes a real one. I think the “Pogo for President” campaign was running at the time. I thought it was a funny idea—I still do actually—but I don’t recall that I ever finished it. Be my guest.

So it wasn’t that I didn’t write, but it really didn’t cross my mind to try to write for a living. I hardly bothered with getting my efforts published. Looking back it seems as if it just didn’t occur to me that a boy from Eaton, Ohio, could be a real writer—which is truly puzzling. Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) was in fact Camden, about nine miles down the road from Eaton, where I grew up. So there was precedent, as the lawyers say.

It was my good friend, George, who first suggested that I try writing for a living. However, I should explain that we have always called him Crazy George. The idea intrigued me but I still didn’t take it too seriously.

In any case, what happened was, I went into a paperback bookstore one day. Now, this in itself was a rather new development at that time, an entire bookstore devoted to paperback books—mostly sexy paperbacks, though I have to say again that the sex was tepid indeed compared to what gets published today.

Anyway, there were these racks and racks of sexy books—heterosexually sexy books, with the occasional nod in the direction of lesbianism but nary a gueen to the realm. I looked through a few of these books and said to myself, “Gosh, I could do this.”

I bought an armful of them, seven or eight I suppose, took them home, read them, and sat down to write my own. It was intended to be a spoof, but not too pointed in its spoofery; I didn’t, after all, want to offend these potential publishers. I sent the manuscript off to the publisher of three or four of the ones I had read, the publisher who seemed to offer the most variety—Brandon House Books in North Hollywood. Milt Luros’ company as it happened, though I did not know this at the time.

In a short time I got a letter back from a Brandon House editor—I’m afraid time has robbed me of his name—telling me he liked the book but it was too short for their purposes. Would I be interested in expanding it?—in which case he would like to see it again and thought probably they would buy it.

I did and they did and within a few months I had in my hands copies of my first novel—The Affairs of Gloria (“The uninhibited story of a free-loving, free-wheeling nympho!”)—or as Fanny later described it, Dolly-Do-Good in the Boudoir.

Now, she had a point. Gloria did do lots of good deeds—I wanted a virtuous heroine—and she also did lots of moaning and writhing, and some of the latter was with women instead of men; but the strongest words in the book, if memory serves, were one “damn,” and elsewhere, “to hell with it!” Furthermore, Gloria did not have tits. She had melons. So far as any other anatomical questions were concerned, for all the details I provided she could have had a feather duster down below; the only thing I made clear was that it tickled many people.

I found the cover rather fetching. I cashed the check (five hundred? seven hundred?) and rushed off another two or three manuscripts to Brandon House, the titles of which have long since fled my memory, and sat by the phone to await the call from the Pulitzer people.

I should perhaps have remembered the advice I had so often offered others, that there are few things in life more fraught with peril than getting what you thought you wanted. The call that came was not from the Pulitzer people but from one Mel Friedman, who worked at Brandon House in a position that never did become altogether clear to me.

“We have been indicted,” he told me, “and are invited to meet for our arraignment tomorrow at the Federal Building in downtown Los Angeles.”

Just at that moment I was standing at my balcony window. In the park across the way the spring flowers made a riot of color. Couples lolled on the grass. There was the thwack of tennis balls from the court nearby. It was, in short, a glorious spring day, except that my toast was burning in the kitchen.

Mister Friedman made his statement with such nonchalance that it took a while for his words to register. “Indicted?” I asked this unfamiliar voice on the telephone. Thwack went the tennis ball. A whiff of smoke reminded me of the toast, but this was no time to put down the phone.

“On Federal obscenity charges,” he explained, in a voice that suggested I ought to have known that.

Obscenity? I was not entirely naïve. Even in those days you could get stag movies, if you knew somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody. There were still pictures too, that left nothing to the imagination. Often they were said to be this or that famous person. I saw nude pictures of actor “David Hardison” (not that I would have recognized him) and “Burt Lancaster” (maybe) and “Andy Griffith” in naked horseplay with a couple of other guys (it really did look like himself but who could be sure? I had certainly never seen anything personally by which I could identify him in this sort of situation).

You could buy little comic books, Tijuana Bibles we called them, featuring rip-off Popeyes and Greta Garbos and Flash Gordons in grotesque sexual contortions, and everyone had one or two of the typed or often mimeographed sex stories that passed from hand to hand, sometimes for years, and sometime also called Tijuana Bibles. Please understand, we had no reference books to clarify these points.

But what did any of that have to do with my lovely Gloria, with her “melon shaped breasts” and her admitted penchant for “manhood”?

Curiouser and Curiouser. I kept the appointment as arranged and found that I was to be charged, along with ten others, with Conspiracy to Distribute Obscene Material. I met my fellow conspirators—Milt Luros and his wife, Bea, the owners of Brandon House and a number of other publishing operations; Mel Friedman, of course; Bernie Abramson, who headed their shipping department; Stanley Sohler, Harold Straubing, and Paul Wisner, who were editors; Elmer Batters, a freelance photographer; and two other freelance writers besides myself—Sam Merwin and Richard Geis. The others were each of them hit with a variety of charges, but I was included only in the first, blanket conspiracy charge, a fact which would ultimately prove significant.

Conspiracy? Didn’t that require some form of communication among the conspirators? I had never met any of these people before, nor communicated with them in any manner. Indeed, until we met at the Federal Building, I had never even heard their names. The only person from the Luros publishing business with whom I had communicated—except for the call the day before from Mel Friedman—was the editor who had written regarding my book, and his only suggestion had been to expand its length. There had been no suggestions, veiled or otherwise, to “spice up” the book in any way, as would later be suggested in court, or to address myself to anyone’s prurient interests. Gloria’s melons were entirely my own. Anyway, that editor wasn’t among my indicted co-conspirators.

It was all a bit Kafka-esque. The more so when, as we were leaving the courtroom, I was met by a man who introduced himself as Donald Schoof, Chief Postal Inspector for the Los Angeles area. I later learned that it was Mister Schoof who had headed the so-called investigation and brought the charges against us. Mister Schoof asked to speak with me alone; apparently the others were all known to him but I was a paperback virgin, so to speak. Or almost, anyway, which I have always thought ought to count in those matters. Mister Schoof muttered—muttered, I swear it, just like in a bad gangster movie—that he could make things easier for me if I would care to switch sides and cooperate with the government.

Now, at the time, I had no problems with cooperating with the government. I had always considered myself a good citizen, if not a model one, and had never set out to commit any crime. Up until now my only courtroom experience was in Dayton, Ohio in 1956, when an angry wife named me as co-respondent in a divorce case.

This was shocking stuff for Dayton in 1956, and created quite a furor. If I live to be normal, which is only the scantest of possibilities, I shall never forget that day. The courtroom, hot and close, a disoriented fly trying to find an open window, and the scent of too much, too musky perfume. Not, certainly, my Chanel, though I was not one to point fingers. And not, I am sure, the Judge’s. A no-nonsense Midwestern burgher, he took his solemn place at the bench. He heard the petition. He looked over his glasses and asked, in innocence, “Is the other woman in the courtroom?”

There was a quick intake of breath and a long silence as he looked from one to the other of us. When finally his gaze rested upon me, I smiled and tootle-waved with my fingers. To say that he blanched would be an understatement. Nonetheless, regardless of what anyone may have heard, I did not blow him a kiss. Yes, all right, my lips did pucker, entirely of their own accord but only slightly; no more, say, than if one had tasted a lemon. I kept them tightly pursed and only nodded to the question he could not quite get into words.

Still and all, co-respondent was guaranteed to get you laughed at by the visitors in the courtroom, as it did, and dirty looks from the judge, but it wasn’t likely to land you in jail. I dressed defiantly for the occasion. I would like to tell you I opted for a broad brimmed hat with a veil and large cabbage roses but I was not quite that defiant. I settled for a fire engine red blouse and black jeans. I had only recently seen Joan Crawford in Johnny Guitar. If anyone knew how to dress to show disdain for convention, it was Joan Crawford. Incidentally, the divorce was granted. The moral is obvious—always dress for success. Also, you might want to think twice about dating a married man.

* * * *

But it did seem to me that if this Mister Schoof’s interest was in making things easier for me, the best time to have approached me might have been before I was charged with a crime of which I was so patently innocent. I have always been a devout coward. And after that debacle in the divorce court I certainly wanted no more legal entanglements. To be honest, had someone taken the trouble to romance me beforehand (candlelight and soft music are givens in this scenario) I would probably in the afterglow of consummation have blabbed everything I knew about Milt Luros—which was of course absolutely nothing. But didn’t they already know that?

Looking back, I can see that what I was really guilty of was criminal innocence. I hadn’t a clue. In my defense, I might point out that I had not bought those initial paperbacks from “under the counter”; no plain brown wrappers, no hasty swaps in darkened doorways. I had walked into a store in broad daylight, had taken them directly from the racks on the walls, and forked over my money. How could I have guessed that forking so openly might involve anything illegal?

I scorned Mister Schoof’s advances. Anyway, his approach struck me as a bit too “after the fact.” I was indignant at being so falsely charged, and kiss me where he might, Mister Schoof was not going to have me on his mattress willingly. I thought then—and think still—that if they had done a sufficient investigation to bring all these charges against all these people, they must certainly have known that this was a first time effort from me and that I had never met with—let alone conspired with—any of these people.

Besides, when I went home and reread Gloria, I was convinced that someone from the other camp had only to get around to reading this lovely book to realize at once what a mistake had been made.

This was America. Indivisible. With liberty and justice for all.…