Читать книгу Spine Intact, Some Creases - Victor J. Banis - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

American History XXX, by Fabio Cleto

Let us go then, you and I, and let us browse a little in America’s cobwebbed garrets. Among discarded rocking chairs and creaky hobby-horses, dusty dolls and moth-eaten dresses, tarnished primers, newsmagazines and grandma’s recipebooks, we may run into a half-concealed cardboard box full of timeworn 4”-x-7” paperbacks, little books with campy, thrilling covers, titles and taglines. Look at these! “Passions and Debauchery Explode in History’s Most Wicked City” (tagline for Paul Ilton’s The Last Days of Sodom and Gomorrah, Signet Books, 1957); “Twilight Lives of Talent & Torment, Man-for-Man in the World of Dance” (Ronn Marvin’s Mr. Ballerina, Regency Books, 1961); “Her Twisted Passion Drove Her to Evil Deeds as She Sought Pleasure in the Arms of Women” (Del Britt’s Flying Lesbian, Brandon House Books, 1963). And what about these? “The Uninhibited Story of a Free-Loving, Free-Wheeling Nympho!” (Victor Jay’s The Affairs of Gloria, Brandon House, 1964); “One Love Was Natural. The Other Was Forbidden—and Dangerous!” (Paula Christian’s The Other Side of Desire, Paperback Library, 1965); “He Burned with a Lusty Passion as He Soared into the Ecstasy of Love—but This Time His Partner Was a Man” (Victor Jay’s So Sweet, So Soft, So Queer, Private Edition Books, 1965). Well, they get more and more outrageously camp! Now, guess what? “For a Price, He Performed Any Act of Degeneracy That Appealed to His Perverted Mind! Sex Hungry Men and Women Offered Their Bodies for His Pleasure!” (Victor Jay’s AC-DC Lover, Private Edition, 1965); “Lancer Knew Damned Well He’d Married a Woman—but the World Refused to Believe Him!” (Stark Cole’s The Man They Called My Wife, Brandon House, 1968); “It Was a Haven for Oddballs…Sex Weirdos in Search of Offbeat Thrills” (Lou Morgan’s Hangout for Queers, Neva Books, 1965). And talking about campy stuff, there you are; “Yoo Hoo! Lover Boy!” (Don Holliday’s The Man from C.A.M.P., Leisure Books, 1966). Oh my, where does all this come from? Who are these authors, what are these publishers? And who on earth read this stuff? Bringing as they did the unbelievable to the spotlight, covers, taglines and titles cried it loud and clear; fifties’ and sixties’ queer pulps emerge from the realm of obscenity.

Named after the poor quality of the pulpwood paper they were printed on, and the queer offspring of late nineteenth-century dime novels and early twentieth-century detective or science fiction magazines, pulp novels and “social inquiries” capitalized, among other factors, on the sensation first created by surveys such as Alfred C. Kinsey’s 1948 landmark Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (followed five years later by the equally shocking Sexual Behavior in the Human Female) and as William Masters & Virginia Johnson’s Human Sexual Response (1966), unapologetically charting the field of human sexual practices, so as to disclose an astonishing variety of experiences and desires that radically undermined America’s wishful self-image of “normality.” The queer, shadowy world was hardly believable, and it needed to be addressed if one wanted to avoid unpredictable consequences such as the tagline for Don Holliday’s Stranger at the Door (Late-Hour Library, 1967) ambiguously squealed; “He Came to Camp!” While Jordan Park’s Half (Lion Books, 1953) and Eve Linkletter’s The Gay Ones (Fabian Books, 1958) wondered “What Was His Body’s Dark Secret That Made Him Neither Man Nor Woman?” and “Were They Pranks of Nature? Or Were They the Third Sex?”, others simply cried that homosexuals were “A Problem That Must Be Faced!” (W.D. Sprague, Ph.D., The Lesbian in Our Society, Midwood Books, 1962). Pulps did face such varied threats indeed; in Anthony James’ America’s Homosexual Underground (Imperial Books, 1965) “An Ace Reporter Covers a World of Vice and Intrigue”; March Hastings’ The Unashamed (Midwood Books, 1968) provided a heartbreaking explanation for such downfall from virtue (“After What Men Did to Her, She Found It Easy to Turn to a Woman For Love”); and Ray Train’s Miss Kinsey’s Report (Chevron Books, 1967) unveiled an appalling backstage to Dr. Kinsey’s intellectual heritage; “It Was Absolutely Unthinkable! To Collect the Money That Her Uncle Had Left Her in His Will, She Had to Make a Survey of All the Townspeople…and Question Them about Their Sex Habits”. Tawdry sexual practices deserved adequate investigation, indeed.

As howled by eyecatching garish covers and taglines, queer pulp promised sordid deeds and baffling passions (“One of the Three…a Sister…Who Strongly Opposed the Basic Convention and Taboos Against Incest”—Louise Sherman’s The Strange Three, Saber Books, 1957), bizarre geometries of desire (“A Lover and His Lady…and His Laddie!”—J. X. Williams’ AC-DC Stud, Greenleaf Classics, 1967) and tales of sheer self-love (“No One Could Admire Him More than Himself!”—J. X. Williams’ Pretty Man, Sundown Reader, 1966). Queer pulp promised to introduce the reader to the strangest of creatures; nymphos, hustlers, swappers, drag queens, ultra-femme vixens from this and other worlds (Frank Belknap Long’s Woman from Another Planet, Chariot, 1960, had “The Body and Passions of a Woman—but the Soul of a Demon”), transvestites and serial killers, hookers, junkies, tramps, luscious beefcake bodybuilders (“Most Men Fall In Love with Women, But Some Men Fall in Love with Themselves!”—Bud Clifton’s Muscle Boy, Ace Books, 1958), psychopaths and freaks of all confessions, “Scandalous Women from Society Dames and Suburban Sinners to B-Girls, He-Girls and Call Girls” (Lee Mortimer’s Women Confidential, Paperback Library, 1961), “strange Sisters” and “Odd Girls Out,” leather-clad lesbians, gay cowboys and detectives, transsexuals, fetish lovers and alien gender-benders. A weird throng indeed, confessing the underground Sin Scene, giving vent to the twilight, sorrow and doom shadowing the sleek façade of mainstream America (J. X. Williams’ Goodbye, My Lover, Sundown Reader, 1966, claimed that “Their Life Was a Sad Song Entitled ‘Good-Bye, My Lover’”). As rumors had been insinuating for years, the sancta sanctorum of the American pursuit of happiness, its dream-factory Tinsel Town, hosted lust and perversion; the shocking truth emerged in novels devoted to “A Hollywood Heyday of Dark Desire!” (Don Holliday’s Home of the Gay, Adult Books, 1968) and to “The Hollywood Scene—the Way It Really Is; Wanton, Luscious, Lusting Hunks of Woman Flesh Who Will Do Anything for Anyone for Fame…and Sensual Thrills!” (Marion Archer’s Thrill Chicks, Bee-Line Books, 1969). Pulps were, in other words, America’s favorite mass-marketed obscenity show before The Jerry Springer Show, webcams and reality shows peopled our night entertainment with freakish case-histories, petty plots, and lingerie show-offs.

Just like many late-night talk shows, these publications pivoted on a voyeuristic fascination for the creepy and ill-regarded. It was an “educational” experience, after all, and one had to face reality, however distasteful; “Never Had So Desperate a Group of Human Beings Banded Together…” (Stella Gray’s Abnormal Anonymous, National Library Books, 1964). One really had to read about them, to keep evil forces at bay; “The Girls Taught Each Other About Love! Every Parent Should Read This Shocking Novel of Adolescent Girls Who First Tolerated Vice—Then Embraced It—Then Could Not Live Without It!” (J. C. Priest’s Private School, Beacon Books, 1959; and please do pay attention to the grossest feature of this book; its author’s name). Of course, there were those fated to reach the gay spell, as it happened to the protagonist of J. X. Williams’ Born to Be Gay (Sundown Reader, 1966); “Fear Drove Him into the Third-Sex Shadow World!” But in case you could read about it beforehand, well, you might even consider checking the Sin Scene yourself, in order to verify the truthfulness of what had been exposed, and to feel relieved for the threats you had been saved from. Moral Beware Guides (or “Don’t” manuals) might thus well turn into weird Self-Instruction Guides (or “Do,-If-You-Really-Insist,-That’s-The-Way” manuals), queering up the guide-style of straight books such as Alex Comfort’s The Joy of Sex; A Gourmet’s Guide to Love Making (1972). The cover blurb for L. Jay Barrow’s Hollywood…Gay Capitol of the World (Dominion, 1968), in fact, promised to chart safer roads to queer Hollywood (“Carefully, in great detail, the author leads over every path of the homosexual community. He names places and people…he reports what’s new in fashions and entertainment. The sex practices of the gay crowd are documented as never before. It’s exciting! It’s a new type of guidebook to homosexual life”). Clearly enough, the revelations on the shadowy underworld might turn out to be, yes, something like David Reuben’s 1969 handbook, Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask), or even like Helen Gurley Brown’s landmark 1962 manual, Sex and the Single Girl; The Unmarried Woman’s Guide to Men, Careers, the Apartment, Diet, Fashion, Money, and Men. Hey, now that I think of it, there is another small, naughty book from that box; it’s Don Holliday’s Sex and the Single Gay (Leisure Books, 1967). No need to argue more on that issue.

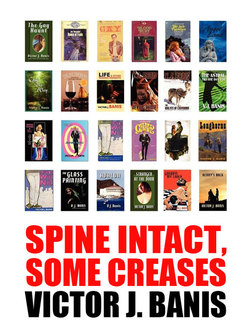

Absolutely; it’s a scandalous, thrilling, threatening, exciting world indeed, the world of pulp paper passions we just discovered in America’s ghostly garret. Are you willing (and legal) to plunge into the world revealed in that half-concealed cardboard box, in a journey à la recherche du temps perdu, or du temps you just missed? If so, the book you are about to read will make an excellent travelogue—and chaperon. This book is in fact penned by a top protagonist of the queer pulp scene, Victor J. Banis, the ubiquitous author—under numerous bylines of both genders—of well over one hundred paperbacks (including eleven of the above mentioned titles, plus the introduction to a twelfth), making him a cult figure in early gay writing. His first gay novel—The Why Not (Greenleaf Classics, 1965)—promised a “Scorching Excursion Through the Gay World of the Lost and the Not-So-Sure…” as a matter of fact. And provided an exquisitely appropriate tagline for the memoirs he would publish forty years later; an excellent guide to books whose authors are “lost, or not-so-sure,” replete with “every path, places and people, fashions and entertainment” of the queer pulp scene.

* * * *

Just like its articulations and protagonists—however formulaic and stereotyped they were—offer an amazingly varied and complex scenario, sixties queer pulp is obscene in a compound way. It sports the whole intricacy of the word obscene, in fact, and it can be useful to delve into such intricacy in order to address the pulp scene. A word of doubtful etymology, obscene apparently derives—via French—from Latin, either from obcænum (a compound of ob, “on account of,” and cænum, “dirt,” “filth,” “foulness,” “vulgarity”) or from obscænus (ob, “tension,” and scæna, “scene,” “communal ritual space”). As the obscene is “dirt,” “filth,” it translates into what is “not for stage.”

The twofold lexical root mirrors the duplicity of obscenity, which refers either to an aesthetical offence induced by something disgusting, impure, abominable, filthy to the senses, or to a moral offence, obscenity being what incites unchaste and lustful ideas, or impure, indecent, lewd, detestable behavior. But also, it enacts the tension between object and social representation, between private and public (requiring that very separateness of spheres it necessarily subverts), presiding over the legal battlefield of obscenity. For the obscene is at one and the same time a descriptive and prescriptive issue, at once a “dirty” object (the privy parts, say) and an action of and on desire (the inducement of immodest thoughts or behavior that privy parts, say, may provoke) breaking the communal rules of what is appropriate to display. On top of that, the obscene is a cultural negotiation (the very idea of standards of acceptable thoughts and practices varies, diachronically and synchronically; it varies in time and space, and it is different as social communities are, so that what is offensive or prurient in rural America may not be so in metropolitan East or West Coasts). Let alone that an object or conduct disgusting to some may be quite appealing to others, whose judgment is silenced, and made itself to some extent obscene.

The obscene therefore belongs both to one’s privacy, and to the communal ritual space, and as such requires the very act of making one’s privacy public, in order to offend the accepted standards of decency, confront social judgment, emerge as a libel against public opinion, “natural decency” and the social order, and constitute itself as, well, obscenity. We may say it implies a double, contradictory normativity, and a dialectic tension between concealing and displaying. On the one side, the obscene is not simply what is “off-stage,” but rather what should be off-stage, the dirt swept under the rug of representation; on the other side, it requires the confrontation with the communal court. The obscene is what should be concealed, but is in fact exposed. (Nobody condemns us for having more or less appealing privy parts; the charge of obscenity would be plausible in case we showed them off in public, which is to say, in case we brought onto the social stage what is “not for stage.”) The obscene is thus inextricably entwined with its seeming opposite, the monster, as etymology (monster deriving from Latin monstrum, “prodigy,” “portent,” “marvelous,” “a divine portent or warning,” also the root for the Latin verb monstrare, “to display”), pulps and tv freak shows—those repertories of human obscenity, making starlets out of the weird, unbelievable, thrilling, threatening, and alluring—illustrate well enough, showing the enduring interest we nourish for what we are supposed to loathe, and the authorization we receive to indulge in illicit excitement by invoking shock and “disgust.”

Obscenity is not necessarily pornographic or sexual in nature, however (wealth and power are obscene, as most of us perfectly know, if arrogantly displayed). But the offence was assumed to be against the prevalent sexual morality within the legal arena, by laws policing and censoring sexual expression. As Martha Nussbaum records in her Hiding from Humanity; Disgust, Shame and the Law (Princeton University Press, 2003), lawyers have had a tough time dealing with such complex and unstable issue, making courts the crucial battleground for the definition of the right to pulp, “pornographic,” queer citizenship, as theoretically warranted by the U.S. constitutional protection for freedom of speech.

Since the thirties, the movies’ Hays Production Code had decreed the obscenity of brutal killings, nudity and homosexuality, along with all kinds of “sex perversion” (adultery, rape, etc.), ruling them out of Hollywood studios productions. As to printed matters, i.e., the pulp battlefield, the test of obscenity in the fifties and sixties was grounded in their representing prurient stuff, while being—in notorious words—“utterly without redeeming social value.”

Such test, along with material conditions of production and reception that we’ll address shortly, primarily accounts for the historical form and circulation of queer pulp fiction; the history of queer pulp is intertwined with the history of pornography, censorship regulations, and obscenity charges. In the mid-fifties, in fact, homosexual characters, friendships and settings left the spaces of indirection they had been relegated to in early twentieth-century queer writing, and made their way onstage, to the center of the novel scene. Still, the greater bulk of queer pulps from the forties and fifties had lesbianism or third-sex twilight stories as its subject matter, and as a rule it was “sociological”—read “pathologizing”—in nature. While lesbianism in these novels largely staged a heterosexual fantasy, and was in fact redeemed by the male gaze—Yvonne Keller, in a splendid essay from The Queer Sixties (edited by Patricia Juliana Smith, Routledge 1999), tags them “virile adventures,” one-handed male readers, written by men and for heterosexual men—both unchained female, freakish and proto-gay sexuality could be converted into “social value” by framing them either as stories that inevitably condemned eccentric (off-stage) sexual subjects to a doomed destiny, or as social psychology investigations in the urban lowlife of unorthodox sexualities (pathological or situational homosexuality, Kinsey-flavored bisexuality, transsexuality as scientific frontier, etc.).

Even in this sanitized context, there were very few titles specifically devoted to gay passions until the mid-sixties, if compared to lesbian, transvestite, transsexual and nympho-themed titles. Just some paperback reissues of homosexual classics, such as Forman Brown’s Better Angel (originally published in 1933), and a handful of novels, including some mainstream press hardcover releases—Truman Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948), Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar (1948), André Tellier’s Twilight Men (1948), Nial Kent’s The Divided Path (1949), James Barr’s Quatrefoil (1950), Jay Little’s Maybe—Tomorrow (1952), James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room (1956).

These scarce fifties’ and early sixties’ gay titles were often successful, commercially if not politically. By and large, in fact, they were dominated by the “sad young man” theme (as Richard Dyer labeled it in The Matter of Images, Routledge, 1993) or, as David Bergman puts it (in the mentioned Queer Sixties anthology), by the “boy meets boy, boy dies” pattern—the only appropriate pattern to a bleak and shadowy underworld peopled by deviant subjects indulging in sin, sex, alcohol, drugs, and crime. Those novels largely deployed classic, elegiac themes in male homosexual early writing; discovering one’s sexual orientation, facing a hostile environment, meandering to the fairy underworld or fighting for a passionate relationship, and finally meeting one’s doomed fate. That is to say, both an elegiac pattern, an acceptance of one’s negative self-image, and the best way to keep representation as “meant for the public benefit.” Given the allegedly “inherent” pornographic nature of homosexual representation, a gay man might be gay only if he and his (miserable) lover “Lived in Fear, Loved in Secret” (as the tagline to Tellier’s Twilight Men 1957 pulp cover eloquently stated), only if one of the two would eventually fade away, so as to restore the order of normality, bring the “redeeming social value” onstage, and call the censor dogs off. One could only be gay if, after all, he clearly wasn’t gay about it, and enjoying himself.

(Such troubled, fluid identity of gay characters and writing is reflected in the unstable generic nature of queer pulp. In the last thirty years, the very possibility of a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender writing has been defined, each with their specific history, features, issues and tradition, but the queer pulp scene did not provide such clarity. Usual elements invoked to characterize lesbian or gay writing—authorship and readership—do not easily apply to the fluid, industrial, obscene, queer scenario of pulp production and circulation, so that the only defining trait immediately available is subject-matter; lesbian-themed, gay-themed, S&M-themed pulps, etc. While most lesbian-themed pulps were in fact written by hets or gay men, gay pulps were largely written by gay authors under pen names shrouding their literary identity in order to avoid obscenity charges, and “polished” by editors, who severely intervened in their writing so as to keep it within legal standards—in some cases, by padding heterosexual scenes in, or by promoting a “sanitizing” cover; both strategies allowed you to be a gay author only if you did not look to be really gay about it.)

There is a story told that a lack of gay-positive images in queer pulp is no big surprise indeed; the fifties and early sixties were the age of McCarthyite culture and of Cold War paranoid homophobia (being homosexual entailed being a likely communist spy; un-American sexual identities might result in anti-American conduct). It is commonly said, in other words, that it took the legendary 1969 Stonewall uprising, and the birth of gay civil rights activism, to make possible the “gay is good” world-view, and reject the “social realism” and/or sensationalism presiding over stigmatized queer pulp images. And yet, unsurprisingly, such historiographic commonplace does not tell the whole story; Stonewall was not a self-generated event, and gay liberation was not born in the seventies, in fact, but in earlier homophile societies activity and magazines, and also, yes, in those “obscene,” contradictory representations made available in that very box we found in our cobwebbed garret, and in the forensic arena concerning alleged “pornography.”

Along with editors, who commissioned materials on the risky line of obscenity and made sure they might appear “socially valuable,” attorneys played a relevant role in pulp publishing houses, monitoring sentences in the field, assisting owners, editors and writers when indicted, inviting them to tone sexual content down, or authorizing them to boost it up as soon as verdicts started dropping charges. A series of sensational trials brought visibility to unorthodox sexualities, and their surprising verdicts entailed a change in legal standards both for heterosexual and homosexual representation. It was Grove Press, with their unexpurgated 1959 edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover and 1961 edition of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, who won the first spectacular trials. While less resonant to the straight audience, a key role for gay pulps was played by the 1961 acquittal of H. Lynn Womack, the king of male erotic photo magazines. Having seen acknowledged the rights of his magazines to circulate in the United States, he would create Guild Press in 1962 and build what would later become a mail service porn empire. News was not always encouraging, though; in 1963 two California-based publishers, Sanford Aday and Wallace de Ortega Maxey, were sentenced to twenty-five years in prison. But signs of a fresher wind blowing were all over the place. The sixties were the decade igniting a sexual revolution, after all; sex issues were treated in popular music, in factual reports and “Do-Your-Own-Thing” manuals, and increasingly at the movies, with censorship loosening its grip (the infamous Hays Code, in fact, was suspended in 1967). Youth rebellion and anti-war demonstrations, the Pill and rubber prophylactics, free love and flower power, the birth of Playboy and Cosmopolitan, drug experimentation, mass hedonism and androgyny, the mini-skirt, the camp craze and women’s liberation, all belong to a multifaceted and contradictory scenario of mass consumption, anti-authoritarianism, anti-conformism, and cultural change. When the Putnam edition of John Cleland’s classic erotic piece Fanny Hill got away with it in 1966, the forensic battlefield decreed—as Charles Rembar, the lawyer who defended Putnam and Grove Press in their causes célèbres, phrased it—the “end of obscenity.” It was not just heterosexual obscenity which was challenged, as a matter of fact; that very same year, William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch got away with it too. The sixties sexual revolution was not just heterosexual revolution, as most social histories may lead us to think.

It is important to stress that it was not just a content issue at stake here; it was rather an issue of what, how and where did it circulate, and with what impact. As we’ve seen, obscenity is not simply an object; it is rather the display of some object that is required to be hidden, and its causing a reaction (at once pleasurable and “repelling”). Pornography had been available for centuries, in fact, to privileged cliques; copies of banned books such as Naked Lunch, Tropic of Cancer, and Fanny Hill were usually smuggled in the U.S., and did have some clandestine circulation. In the monitoring of its social effects, an unorthodox practice was something if represented in a hardcover novel of some literary complexity, because that limited and safeguarded its circulation. Such representation would merely reach, in fact, a highly literate and rather affluent readership having access to literary journals and upper-class newspapers (which, in case the book was too “dangerous,” might even refuse to run an ad for it, as it happened in 1948 to Vidal’s The City and the Pillar) and to metropolitan bookstores. The circulation of that unorthodox practice was, in some degree, safely kept off-scene enough, so as not to produce obscenity charges. That very same practice would be quite different, on the other hand, if represented in a paperback book, which was much cheaper, required a less literate readership, and was available next door. This is precisely what queer pulps represented in the sixties, enhanced as they were by the distribution that had been inaugurated in the late thirties by Penguin Books (who also won a trial that removed the ban on Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960) in the U.K., followed by presses like Popular Library, Fawcett Gold Medal, and Pocket Books in the U.S. All of a sudden, books staging “not for stage” identities and conducts were all over America. No more smuggling, or high cultural capital, was required; they could be found in sleazy newsstands, soda shops and grocery stores, sold “over the counter” or displayed in rack stacks, and with effective self-advertising covers and taglines. You could also carry them home discreetly, by slipping them into your pocket.

Significantly, the most pervasive censorship activities were conducted by Postal authorities, who might refuse to circulate books and exert surveillance on publishers and writers, so that the fight for queer visibility had courts as its battlefield, editors and writers on the one side, aided by their attorneys, obscenity laws—with Post Offices as their armed forces—on the other side. In such traffic warfare, pulps played a role indeed in changing the self-image of America. The readership for paperback novels had been boosted by military authorities, who promoted cheap editions of American classics—a huge number of books were published by Armed Services Editions—to benefit troops in World War II; cheap entertainment, role models and motivation for the heroes of American identity, freedom and constitutional rights. They served this end far beyond the first intentions of the military forces; when the battleground moved from trenches and warships to the legal courts, pulps were a relevant factor in reassessing what was legitimate to stage as part of American identity and constitutional rights—precisely because a potential readership had been created by such mass-produced American classics, and liberal consumer society models.

First came the success gracing John Rechy’s City of Night, issued by Grove Press in 1964. A bestselling exposé on the promiscuous and degraded underworld of hustlers and drag queens, it introduced the queer scenario to a wider reading public, and with a sensation that is testimony to the furtive titillation that the reign of neon-lighted obscurity, the aura and fascination of obscenity, exerted on both queers and ‘straights.” Then came signs of a pulp deluge. The year 1965, in fact, inaugurated a flood of gay pulps, and announced the Golden Age of the gay paperback. Overnight, within a few months, an impressive number of gay pulps (thirty paperback originals were published in 1965; more than a hundred were issued the following year), and a whole throng of gay representations, were made available. Hey, there were thousands of readers out there, there were writers ready to give them the stories they were looking for, there was an adequate production system, and an excellent distribution line. There lay a huge potential market, and the gay pulp industry was born. With a number of presses on both East and West coasts (Greenleaf Classics, Pyramid Books, Paperback Library, Classic Publications, Brandon House, and dozens of imprints) ready to seize the opportunity to harvest the field of increasingly explicit (albeit rather tame, by today’s standards) gay writing.

The reality depicted in gay pulps, however, was not in itself positive; the weakening of censorship strictures did not automatically imply a gay pride. Characters were stereotyped, sexploitation was the dominant feature, and writers still largely used the cover up of pseudonyms, as nothing guaranteed that the cultural wind would not, abruptly, change its direction again. (And it did change, occasionally; as late as 1970, one of the major presses in queer pulp, Greenleaf Classics, was indicted and condemned; the Supreme Court confirmed the verdict in 1975, sending pulp guru Earl Kemp to prison.) In the bourgeoning pulp industry of the mid-sixties, few book contracts were signed (better not to leave traces), books were written in days, manipulated by editors for both legal and market reasons (pulps usually had standard length), attributed to pen or house names, and issued by analogously ubiquitous publishers, whose name and location shifted frequently. A standardized production for standard plots, characters and length, plus a fixed rate of sex to feed the market; that’s how the production line of queer pulp beauty worked, and one may well say that it apparently had little to share with the gay pride, poetry and art of the seventies. What it did share, though, is the political relevance of representation, as inherent to the very possibility for self-recognition; despite their industrial nature, despite all their literary and political flaws, pulps were the first mass representation available to generations of (embryo) gay people, as they made the obscene into a sensation. Gay characters and plots progressively lost their lurid nature, developed a more ironic and sexually explicit stance, and peopled a whole new variety of gay fantasies (including gay westerns, thrillers and detective stories, war stories, gay spoofs, etc.), offering a queer mirror that enabled queers—and heterosexuals, to some extent—to literally come to terms with their own self-understanding.

The Golden Age of the gay paperback was rather short-lived; it lasted for the brief time span between the 1966 lift of bans on Fanny Hill and on Naked Lunch, and the actual “end of obscenity” in the early seventies. A landmark legal statement took place in 1973, in the famous Miller vs. California case, whose verdict changed the test regulating obscenity charges. The three-pronged Miller test assessed the obscenity of a work i) that “the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find [to appeal] to the prurient interest,” ii) that represents, “in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct,” and iii) that “taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.” But the Miller test was quite ineffective; the Supreme Court, chaired by Chief Justice Burger, had to acknowledge that “community standards” must be locally defined; as to “artistic value,” Andy Warhol and John Waters had shown that it may be found even in supermarkets and in filth (well, Waters’ Pink Flamingos made drag actor Divine the ultimate trash superstar by having her eat dog’s fresh poo). The frailties of the Miller test unleashed the gates to the season of commercial, mass pornography. In the same years, as gay pulp grew more unabashedly explicit in its sexual content, and social psychology justifications became less stringent, the birth of a gay activism following the Stonewall riots, and the increasing legitimacy of a gay identity, made pulp redundant. The two-fold nature of pulp, its pornographic and socioliterary self-justificatory nature, was split. Pornography acquired its own right to exist as such, and the possibility for gay writing, of high literary value and positive self-representation, was envisioned. Depriving them of their obscenity, the early seventies decreed the end of pulps.

It was a new freedom of expression, gay activism, and the fight for gay rights to constitutional happiness, that brought gay pulps to the cobwebbed garrets, and into the garbage bins of history. Back off scene, to the obscure and shadowy realm that they rightfully belonged to. Until, some thirty years later, cultural critics, second-hand book dealers and postcard companies unpacked those half-concealed cardboard boxes in their garrets, ran into these campy revenants, and reconsidered their worth, as collectibles, memorabilia, and significant cultural tokens. Pulps offered a Barnum of popular beliefs on what being queer before Stonewall was like. They were not just amusing Kitsch, a source of camp-flavored nostalgia for both queers and straights; they were documents on the time when pulps provided a queer mirror to many people giving evidence that they were not the only “freaks”—once small-priced, but now precious documents on the fragmented identities, desires and struggles out of which seventies liberation and identity politics emerged. Pulps had found a new market, a refurbished stage. Yes, they were obscene again.

* * * *

The history of pulp fiction is not only the history of mid-twentieth-century obscenity regulations, charges, trials and verdicts; it is in itself an obscene history, both invoked and hidden by the “(hetero)sexual revolution” rhetoric, and the Stonewall mythology of gay (self-)liberation. Pulps entail that hetero and queer sexual revolutions were part of an economic negotiation between representation, and market strategies, culture industry and pornography, a negotiation in which the very categories of heterosexuality and homosexuality cannot simply be distributed into clear-cut fronts, even more so into fronts of heterosexual conservatism vs. homosexual progressive agency (it was a queer scenario, after all, that preceded identity politics). The return of pulps does set up in fact an agenda for a more complex cultural and social history, an agenda taking into account the variety of actors and factors inherent to cultural production. In other words, the history of pulp fiction summons what is still much silenced in American history—and it is in itself a necessarily pulp, fictional history.

While some pioneering, classic studies from the early eighties—say, Barbara Grier’s annotated checklist in The Lesbian in Literature (Naiad Press, 1981), and Michael Bronski’s Culture Clash (South End Press, 1984), outlining the role of porn in the “making of gay sensibility”—offered valuable, albeit unsystematic, insights into the role played by queer paperbacks, in the last few years a number of invaluable resources have been made accessible. Relevant critical readings have been published by established presses, including, most notably, Dawn B. Sova’s Passion and Penance; The Lesbian in Pulp Fiction (Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1998), Jaye Zimet’s Strange Sisters; The Art of Lesbian Pulp Fiction, 1949-1969 (Penguin, 1999), and Chris Nealon’s Foundlings; Lesbian and Gay Historical Emotion Before Stonewall (Duke University Press, 2001). Meeting the desires of those who also want to read the pulps themselves rather than just reading about them, a few classics have been reissued, such as Ann Bannon’s fifties’ novels (including Odd Girl Out and I Am a Woman, reprinted by Cleis Press), and the excellent anthology—Pulp Friction; Uncovering the Golden Age of Gay Male Pulps—Michael Bronski edited for St. Martin’s Press in 2003. In case you want to go less “classic,” well, library pulp special collections have been established, and second-hand bookstores have been made internationally available to fans and scholars through the Internet. Nowadays, in other words, you don’t have to be literally nosy about your neighbor’s readings and look for his naughty boxes, in order to run into pulp imagery. You just need to go to a library, or a bookstore, or have Internet access, which will introduce you to many websites devoted to pulp memorabilia, souvenirs and collectibles; the “dirty” snooping job is being done by scholars, webmasters and librarians on your behalf—so you may just sit down and enjoy. And of course, you can still wonder about your neighbor, if you fancy doing so.

These charming ghosts, restoring pulps to visibility and interest (both critical and commercial), did not therefore come back spontaneously; they are the result of cultural research that cannot firmly rely upon the institutional tools of historical analysis. Such research is best achieved as a fictional, pulp history, insofar as it can only be done by ransacking the trash bin of history; by skimming through that huge, virtual archive of tarnished pulpwood paper that lay half-forgotten across the country, reading about pulps in underground publications such as the journals published by early homophile organizations, and by looking for the protagonists of that era, enhancing the very possibility of telling a history though their stories, gossip, covers, and pulpwood.

The sex wars and revolution of the sixties and seventies had paper and images as their armies; a fierce cultural battle, we have seen, was fought in representations, and in the very legal possibility of “re-presentation” (i.e., mass-printing and distribution). A cultural history of the sixties, sated with icons and iconoclasts as they were, should therefore account not only for movie stars, fashion and political leaders, art and pop music stars. It should also account for the heroes of the pulp theatre of obscenity; authors, editors, attorneys, cover artists—and characters. It was in characters, in the obscenity of their plots and desires, in fact, that the pulp freak show was created. It is no accident that histories of pulp are told through these covers and characters, as the stars of a pop cult for the demi-monde that was, insomuch as it was obscene, at once underground and fully exposed, at once bordering on the illegal and evident in the pulp dazzling covers and “points of distribution.” Just like the pulp theatre once transformed weirdoes into starlets, time has turned them into vintage smut gems—or, if you are in a metaphorical mood, it turned these cultural sand-grains into oyster pearls.

Of all the starlets and heroes of the Golden Age of the queer paperback, one cover and character surely stand out as a recurrent presence in visual and critical overviews of the queer pulp era, so as to become the ultimate star of sixties queer pulp culture; it’s Jackie Holmes, the protagonist of Don Holliday’s legendary series opened in 1966 by The Man from C.A.M.P. (yes, the book sporting the Yoo Hoo! Lover Boy! tagline, remember?), followed by eight other titles in the next two years. There he was, on the foreground of an optical pink and blue vertigo pattern; stylish haircut, velvet jacket and waistcoat, embroidered pochette, silk shirt, leotard pants and gleaming leather boots—a flamboyant blond-haired queen indeed, posing in his sunglasses, winking looks, arm akimbo and cigarette holder, while keeping a white poodle on the leash. Quite the stereotype of a sixties homosexual and his pet, we would say; but in that duo there was evidently more than meets the eye. In fact, they were both undercover agents. Jackie Holmes was the queer outcome of the Bond mania that flooded the U.S. in late 1964, with James Bond and Napoleon Solo, that Man from U.N.C.L.E., raging in theatres, on tv and in magazines, fighting communist spies and deviate corporate capitalism worldwide—and, in their spare time, reasserting the male gaze and patriarchal order that were under threat. Yes, for the sake of the nation (nothing personal; just a means to a good end), they had to do their duty with that throng of blond and brunette playthings. Jackie is himself the top agent of an all-powerful secret Agency, but one that is far less banal than the Bond herd. His Agency is eloquently enough named C.A.M.P. (no, we don’t ever get to know what the acronym stands for, but that’s what camp is all about, isn’t it?), an Agency dedicated to “the protection and advancement of homosexuals” throughout the world. The luxurious offices of C.A.M.P. may be found in the back of rundown bars, via—of course—their toilets. A blond sex bombshell, a diamond expert and a vintage cars connoisseur, from such offices Jackie Holmes steps into the world; making all heads turn, he fights evil plots, wins over villains—and crushes hearts—of all sexual confessions. He inexorably brings Interpol straight agents into his bed, as a matter of fact, so as to make them into notches on his huge wooden, penis-shaped trophy totem. As to Sophie, the white poodle co-starring in that book cover, she is his appropriately undercover pet; while looking harmless, she reveals “razor sharp teeth” and is “trained to kill.” Wow, now that’s something different indeed.

The symbolic value of Jackie Holmes and his C.A.M.P. confreres in mid-sixties pop queer culture can hardly be overestimated. A few months before Susan Sontag had brought camp travesty, aestheticism and inverted hierarchies to mass consumption; her famous Notes on “Camp” essay, first published in Partisan Review in Fall 1964—right on the verge of the Bond mania outburst (Goldfinger premiered in New York in December 1964)—captured the Zeitgeist so much that the New York Times and Time magazine immediately reported on it, alongside instances of the Bond craze, and pushed throngs of Americans to flea markets, looking for that piece of endearingly “failed seriousness” Sontag had taught them to love. By “betraying” (her term) the camp secret code, by acting as an intellectual spy and divulging camp to the masses, Sontag herself—“Miss Camp,” as she was tagged at the time—would thus become a media celebrity, and an emblem for sixties mass “masked culture,” one that, by adopting camp as its catchphrase, offered intellectuals a way to reaffirm their aesthetic supremacy as taste-makers, precisely because they derided modernist aesthetic categories, laughed away paranoid homophobic McCarthyite culture, and exhilaratingly espoused queer popular culture. But Jackie the queer icon was more than just another mass icon, however extraordinarily significant Sontag and Bond were. Jackie staged a more elitist cult, both more exclusive and popular, for he was no icon to New York literati, but to thousands of obscure readers who bought his adventures in newsstands (hence, he was more “popular”), and had access to a deeper underground (hence, his more “exclusive” nature) deployment of the camp travesty. Jackie’s C.A.M.P. Agency was a celebration of camp as gay ‘survival strategy,” the strategy allowing generations of queers to cope with a gloomy reality—by letting them find thrilling spectacles, self-fashioning theatrics, identity and community in flamboyant parody, behind closed doors and in rundown bars, amidst human debris and desolation. But Jackie himself did more than that. He showed the very possibility, before Stonewall, to be gay and proud, to be both a committed social activist and a gay Don Juan. Of all queer pulp images, name one who better qualifies as spy queen.

As a secret agent, underground celebrity, icon and iconoclast, Jackie is an apt figure for sixties queer pulp culture; a paradoxical culture indeed, grounded in pop secrecy, in pseudonyms and sensation. He captures and embodies the sixties tension between paper agency, sub-cultural rebellion, survival strategies, and undercover self-recognition. He vanished in 1968, but he lived as a legend in the heart and mind of all those who had read his pulp adventures. Until he reappeared, in web pages and in critical studies, leading the ghosts from the Golden Age of the gay paperback. And eventually, this ultimate pulp star and hero made his comeback as a reissued classic in early 2004, when Harrington Park Press published three of his stories in one volume.

If the top agent of C.A.M.P. is the one star character of that era, the star author of pulps actually resembles Jackie in many ways, as far as some pictures from the sixties suggest; same hair and profile, in fact, same heartbreaking, classy, naughty looks. And in one picture, he can also be seen with a white poodle. Unsurprisingly so, for this is Jackie’s creator. No, his name is not Don Holliday, as the book cover stated. The author of an undercover star character and series was, most appropriately, an undercover star author. Yes, you are—I wonder how you can not be—on the right track. Just like Sontag, Bond, and Solo, the other media spy celebrities of those months, Victor J. Banis had himself made his appearance in the New York Times in late 1964; not so much in the Arts & Entertainment pages, though, but rather in the forensic news, for he was indicted in an obscenity trial in Sioux City, Iowa, on the ground of his first novel, The Affairs of Gloria (yes, you met that “free-loving, free-wheeling nympho” above), issued by Brandon House in 1964 and nominally authored by “Victor Jay.” Upon acquittal, Victor Banis did not orderly retreat to other, safer professions; as Don Holliday, Victor Jay, J. X. Williams, Jay Symon, Jay Vickery, Bob Michaels, Victor Samuels, Victor Dodson, Jay Dodd, Dodd V. Banson, or anonymously, he outpoured a huge amount of pulps, including Jackie’s adventures, so as to become the most prolific author of the Golden Age of gay pulps, the underground chief of writers like Richard Amory, James Cain, Phil Andros, Chris Davidson, Ed Wood Jr., and possibly the most read author of gay materials in the world—by the early seventies, Banis had sold around three million copies of his books. In that brief time span, Banis was a big underground star indeed, shrouded in many pseudonyms, as elusive as his books were ubiquitous. When gay pulps lost their momentum, he donned another series of pen masks (Jan Alexander, Lynn Benedict, Jessica Stuart, Elizabeth Monterey), and became “the Queen of Gothic Romance.” Then he moved to historical novels, published under the pen name “V. J. Banis’—but right when his literary mask moved closer to his own real name, in the mid-eighties, and he eventually seemed ready to give up the safeguard of his caped crusader identity, well, he vanished. He was no longer heard of, on the literary scene, and the fog of time closed around him. What better star, for the pulp scene, than an undercover star author, who avoids the Time magazine front page and downtown bookstores in favor of masked, sudden and short-lived appearances in grocery stores and soda shops, and then evaporates, leaving behind himself only his textual ghosts?

* * * *

In the last few years cultural critics, librarians and book-collectors have found themselves playing the part of characters in a hardboiled, sexy detective story; they turned into sleuths, sniffing for paper clues and traces as they went after lost paperbacks and those who authored them. It wasn’t an easy task, in fact; they first had to try and unveil the real identity that lay behind the cover of their collective or personal pseudonyms, and then they had to try and dislodge them from their forced retirement. Real-life versions, as these pulp heroes are, of the superheroes of the 2004 Pixar movie, The Incredibles, such hunt, if successful, is bringing them back onstage. They are not usually required to save the world, but rather to do what they were great at doing forty years ago; they are asked to tell their stories, as witnesses and protagonists of an era of most radical social and cultural transformation. Their personal memories turn out to be among the most extraordinary documents we may produce in charting the obscene social history of pulp.

In a recent article he wrote for the New England’s gay and lesbian newspaper Bay Windows, Michael Bronski tells us a witty story about his detective work in 2002 as he was looking for the authors of the pulp classics he excerpted in his Pulp Friction collection. He was struggling to trace Victor Jay, the author of a gay ghost story, The Gay Haunt (The Other Traveller, 1970). Textual traits led him to suspect that Victor Jay, Don Holliday, and a number of other writers might in fact be the same person, and the only likely real name among the throng of pen masks this textual subject sported was “Victor Banis.” But even in case the guess was right, how could the Sleuth Critic trace him on earth? Well, the specter of Edgar Allan Poe’s purloined letter must have materialized in Bronski’s mind—in order to decrypt the most obscure secret, he might well try and look at the most visible place of all, at the very index of visibility; there a “Victor J. Banis” was in the white pages of the phone book, living in San Francisco. And answering the phone.

I was even luckier than that. I had been frustratingly looking for that Man from C.A.M.P. series for years, in fact, to little end (that was before the Internet made things much easier). As in late 1998 I was completing a book on camp, I went to the University of California at Berkeley (thanks, Chris, for inviting me there), and I decided to stay in San Francisco (thanks, Gian Piero, for suggesting that). With no connection whatsoever to my actual research, I met Victor. A friend (thank you, Fulvio) had told me that he had been a writer, once upon a time, and gosh, that’s part of my job, getting to know writers better. So I asked him what sort of stuff he had written, back in the sixties. And there he was, that Man from C.A.M.P. in person, the author of the books I had been searching for years, the creator of the Jackie Holmes star character and—as I was to discover—of numberless other starlets of the queer freak show. Now, that’s what I call serendipity.

Later, I was even luckier. I found a good publishing house, the Haworth Press in New York, that was interested in bringing back to print Jackie Holmes; I thus edited the 2004 reissue of three C.A.M.P. adventures, and interviewed Victor for that book. So, I learnt that he had decided to write his memoirs. Of course, that’s what big stars are expected to do, aren’t they? And I was so lucky as to read them—not just that, I could edit them. In doing so, I had a chance to fully appreciate the fact that Victor J. Banis is no mere starlet, as dozens of pulp authors and characters have been. Just like his darling creature Jackie, he is certainly the one big star of that scene. Even better, he is its superstar. Not so much, or just, because he possibly wrote more books and sold more copies than any other gay pulp author, in that half-decade. Rather, because his work and memoirs are a cipher of pulp authorship, and best illustrate the dynamic of superstardom, one that hypes, parodies and demystifies the ideological apparatus of stardom.

Let me articulate on this point, which I take to be a central issue both in pulp fiction, and in the remarkable life and work of Victor J. Banis. As we learn from Chapter II, in an ironic deployment of the “artist as a young man” trope, Banis remembers how he did not set out, in his early days, to become a writer. He basically set out to become a stage actor of any kind, and he tried his chances along different routes to the spotlight; dancing, acting, singing, modeling. Banis confesses that, in all these professions, he inexorably made his way to the stage, but only marginally so, as he managed to become “only a super—or a supernumerary, to be exact.” In such self-ironic, nonchalant remark, Banis inadvertently provides us with a key to his career and field. For it was when he struck on writing, that he turned this recurrent failure of being “only a super” into the epitome of his later success and underground star identity, as being “really a super.” It was when he found an appropriate stage, the pulp stage, a stage pivoted in fact on the very idea of “the super”—the super prefix (“over,” “above,” “on the top,” “higher in rank, quality, amount, or degree,” “beyond,” “besides,” “in addition”) standing at once for contradictory conditions, for what is “very great, or too great,” dictionaries tell us. A cognate term of extra, super stands in fact both for what is superior, “exceptional,” “remarkable” (a meaning best represented in recent use which, lexical repertoires such as the Oxford English Dictionary tell us, designates “a person, animal, or thing which markedly surpasses all others, or the generality, of its class”), and for what is added, “over the top,” “inessential,” “in excess of what is usual, or of what ought to be.” That’s what pulp fiction—a “paraliterary” and generic writing, bringing excess, sensationalism, freak subjectivity to the spotlight—represented, in fact; a whole stage whose essence is the parergon (i.e., what lays beside and beyond the artwork proper), celebrating the marginal, unnatural, unusual, superfluous and discarded, what in other words exceeds the “hard facts” of history; the feather boas, zoot suits and second-hand dresses that we may run into by ransacking the trash bins of cultural and social history. As to its protagonists, its chief characters, authors, cover artists and editors, it is only appropriate that they reach not so much a banal kind of notoriety or celebrity—the one gracing mainstream figures—but rather the paradoxically underground condition of superstardom, as emblems of the realm of “the super.”

Super-stardom may best be addressed by summoning Andy Warhol, who allegedly coined, in fact, the very term superstar, and ultimately articulated the grammar of superstardom aesthetics. Stars like Candy Darling, International Velvet, Ingrid Superstar, Ultra Violet, Mario Montez, Holly Woodlawn, Edie Sedgwick, Joe Dallesandro, Viva, Ondine et alii were no mere stars; they were Factory products, a counter, serialized version of the Hollywood industry of exceptional individuality. As such, they were superstars in the compound way inherent to the super prefix; they were so, in fact, both as “hyped stars” and as stars of “the super,” of trash and the leftover. In The Philosophy of Andy Warhol; From A to B and Back Again (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975, p. 93), in fact, Warhol states that he liked “to work on leftovers, doing the leftover things,” for “[t]hings that were discarded and that everybody knew were no good […] had a great potential to be funny.” The Factory, in other words, was a recycling industry of individualities; “You’re recycling work and you’re recycling people, and you’re running your business as a byproduct of other businesses.” In describing the queer, derivative economy of his “funny” cultural (re)production, Andy Warhol was envisaging the campy aesthetics of pulp stardom, the role played by superstars such as Victor Banis, and the very logic of his memoirs. The pulp superstar, secondary as s/he is, enacts a parody of “proper” stardom and iconicity, a travesty of celebrity culture and the consumerist economy of exceptionality, originality, iconicity, and emblematic value, that one finds in Oprah and Hollywood culture. A “transgressive reinscription,” it might be called in academic jargon. A less sensational, more urbane version of the stardom enacted in freak reality shows and gutter press revelations, and yet rooted in the very same “confidential” nature (obscenity, confession and stardom are intertwined discourses, founding and reinforcing each other), talk shows and interviews are the sites in which star figures are expected to unfold their private side, “show” their real (to reel) soul and personality, open up their heart to America—and by doing so, they are supposed to bring us to the heart of America they epitomize, to the specters of emotional stories, longing and fears, they embody and direct for their fans.

This is precisely what Banis’ memoirs enact and provide, in fact, albeit on a minor/superior, “obscene” theatre. As with mainstream star autobiographies, Banis’ personal memories offer invaluable insider knowledge on the “super” stage he was a protagonist of, on the gay book market he actually contributed to create, and on queer pulp authorship. Part social history, part emotional history, these “remembrances of a paperback writer” bring us indeed to the heart of America, and to its most private fictions. In an extraordinary tale entwining personal and collective histories, a tale bringing us from fifties McCarthyite culture and naughty superhero comics to the sexual revolution and gay rights fights of the seventies, we are thus introduced to the early, pre-Stonewall gay scene of marginal lives and cravings, bars and friendships, to the celebrity cruising and Hollywood mystique that structured both straight and queer identities, to the role sex played in boosting at once the porn industry, the book market and social change, and to the spy-like, undercover, hit-and-run lives that pulp authors and editors led. New, bizarre chapters in American history are thus unfurled, chapters in a pulp, graphic, emotional and criminal history, one that interlaces public and private narratives, under the aegis of obscene superstardom, bringing to the centerfold the public/private, showing/hiding dialectic inherent to stardom. (A dialectic best figured, as a matter of fact, in the sunglasses sported against the paparazzi’s flashbulbs, representing the contradictions inscribed in the star identity, with both her need to publicize her work, passions, love affairs, and her opposite yearning for privacy.)

It is only appropriate that such chapters emerge from the anecdotes of a man that first reached the spotlight, and faced flashbulbs, as a “criminal star” indicted for conspiring to distribute obscene materials, the deeds of a free-wheeling, free-loving nympho. A figure that, Banis confesses in his opening remarks, is “a very private person,” embarrassed by the idea of making himself into a public show. That’s precisely how he managed to live, however, as an episode in Chapter 4 illustrates. When as a youth he faced the threat of an assault, he managed to escape violence not by facing the robber, but rather by adopting the ruse of intelligence; his self-defense was in making recourse to his talking talent. So, it was by means of a show, by staging his seductive wit and yarning flair, that he managed to keep the villain under control; he managed to escape physical violence and, metaphorically, to hide. By displaying himself, he concealed himself. That’s how the gay pulp author negotiated the very possibility of his speech and existence, in fact, before gay identities started acquiring the rights to full citizenship.

In this respect also mirroring his pop spy star Jackie, an undercover celebrity doubling the visibility/secrecy paradox of the James Bond star image, Victor Banis acts as a spy figure in writing his memoirs. His insider’s knowledge trades in obscene information about the U.S. culture industry and sexual revolution, about the who, when, where and how of the criminal history of pulp’s undercover agents—reading his “gossipy” history, naming places and people as it does, turns out to be an issue of intelligence, in fact. Such “intelligence” is precisely invoked in a confidential narrative, the star memoirs genre (one appropriately deploying the double, public/private dynamic of confession on the double, private/public star identity), especially when related to the confessional stage of pulp fiction. Another episode from Banis’ remembrances aptly illustrates this issue. In Chapter 12, while discussing his case-history books production, Banis tells us that he had to amass information on the infinite variety of human experience and sexual entertainment. The pulp sociologist thus had to interview wife swappers, fetish-lovers, and the queer likes. There we learn how Banis gained access to weird family albums indeed, and how he found himself acting as a non-judgmental “father confessor,” one willing to collect the tales of those sins and “abhorrent practices” that even the two major institutional confessors of modern society—the priest and the psycho-sexologist, who in different ways offered scolding and invitation to conform (be it in contrition or “treatment”) rather than validation, rather than the neutral acknowledgement intrinsic to just listening—were unlikely to be told in their respective confessional rooms. Just by noting down the funniest practices, the pulp author was providing them a legitimization, as social and discursive practices. In offering America’s Wicked Queens the validating reflection of mirrors (“Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest one of all?”), by offering a magic self-reflecting surface to untold desires and stigmatized selves, the pulp author was a confessor that enabled self-recognition and acceptance of unorthodox identities.

In reading a pulp star’s confessions, we are thus reading something like America Confidential—America’s heart and soul, did we say? Unsurprisingly so, as a matter of fact, if we link the pulp theatre of obscenity to the twofold confessional nature of stardom that cultural criticism has unfolded since the 1972 publication of Edgar Morin’s classic study, Les Stars. The private/public existence of stars implies a confessional nature, both on part of the star, who constantly confesses to her fans by means of interviews, appearances etc., and on the fan, whose identifying adoration, in addressing the star identity as guidance and role model, confesses and “writes” her/his own subjectivity. The pulp superstar author may thus be seen as the father confessor of America’s most recondite fantasies, made up of celebrity culture, sexploitation and Playboy empires, “Petunias,” “McDonalds” and bovine Salomes—names and institutions you’ll have a chance to get to know better, and fully appreciate, as you read Banis’ memoirs.

These pages are the legacy of a queer father confessor, and a queer role model. In them you’ll find many things that may sound rather loosely related, or utterly unrelated, to his pulp work. You’ll find some juicy gossip, of course, and a three-chapter writing manual, organizing the tips he imparted to many writers whose work he promoted, in the late sixties and seventies. You’ll find an evaluation of gay writing, discussing figures that have either emerged from the Golden Age of pulps, or established themselves as major authors in the newly legitimate gay market of the eighties and nineties; the role he played in gay pulp authorize him in fact to speak on gay writing—not from “above,” we may say, but from his insider’s privileged knowledge on the production line of the gay culture industry. But you’ll also find considerations on religion and the soul, on how to “live with a style,” from ethics to manners to drinks and food (yes, there are even some cooking recipes). Does this strike you as irrelevant? Hey, what did you expect from a superstar’s autobiography? Ever read Elizabeth Taylor’s or Barbara Cartland’s memoirs? While these may well be marginal issues in an author’s life story, they are technically part of the star mystique. In dispensing pills of wisdom on life, death and some details in between the two, the star offers her fans the guidance that is her duty to provide as a role model. Stars do live in passions, and in the following of fans, in the emotional energies of those who identify and believe in them. How can you be an emblem of modern subjectivity, and ideologically central to our existence as social subjects, if you don’t confess your most private feelings and experiences, how you dress and make up, how you cook, eat and prepare your drinks? Marginal issues have such value, and even more so on the “super” stage—one that parodies the identity formation value of mainstream stardom, and at the same time provides alternative role models. Banis’ superstar image may be less flashy than, say, John Waters’ Divine, and yet it provides a model that many would acknowledge, one inspiring the values of curiosity, tolerance, and understanding.

The heart and soul of America we can read in Banis’ confessional, as a matter of fact, is not only peopled by secreted passions, social struggles, and some extra dietary tips. In his entwining of personal and collective histories, you’ll also find the stories of small town provinces like Eaton, Ohio, where Banis was born, and the example of a “family without familism,” as French critic Roland Barthes tagged it in his autobiography, Barthes par Roland Barthes (1975); a family devoid of the tyranny inscribed in “Nature” and the common sense.

Banis’ was a quite large, poor family, and nonetheless such family scene provided him with a profound sense of community, with a personal model for the sense of “social family” shared by many gay people (those that, expelled from their own biological family, rebuild it in the social spaces acknowledging their right to exist), and a utopia of solidarity and integration. His large family, mother father and eleven kids, plus aunts and uncles, Banis remembers, was a community in which one would be accepted independently from one’s class, means or sexual orientation; the only reason for being rejected was one’s pretending to stand above others—or, in other words, one’s refusal to accept one’s place as a peer, sharing the little they had, and making room for diversity and difference. This model may not have been realized in Banis’ life, as we all know (even the gay social family is all too often reduced to a ghetto or a lobby), but it certainly stands as a model to look for, as an ultimate utopia of tolerance and understanding. A utopia, of course, that as such won’t be found in the real world—but that’s precisely the value of utopias, those ideal figurations that, Oscar Wilde said, make humans crave for something better, and achieve some progress. This is a much better American dream, I do think, than, say, the one bringing third-rate movie actors to become governors of California.

This is the heart and soul of America that Victor Banis shows us, and the dream of integration that, as a superstar, he stands for. For there is more to the obscenity of pulp than soft-porn and sensationalism, irony and parody. The history of pulp is an emotional history, after all. It was Barthes again, in Fragments d’un discours amoureux (1977), who stated—in the seventies, when porn “came of age”—that there was a sphere, more than pornography, increasingly relegated to the status of obscenity; the sentimentality of love.

The most recondite aspect of pulp history, the ultimate obscenity to be found in Victor Banis’ memoirs, and what an intellectual may be embarrassed to confess to, is its emotional side. The love and affection, thinly disguised in irony, breathing though its pages.

* * * *

Let me close this introductory essay to a confessional narrative with a brief, highly personal note. I mentioned above my casually running into Victor, in early 1999. I knew very little on pulps, at the time; and I had just seen a number of movies whose pathos had kept lingering in my mind, and whose direct relevance to that serendipitous meeting, and to my later interest in pulps, took me some time to realize. P. T. Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997), on the raunchy SoCal porn industry of the seventies, starred Mark Wahlberg as Dirk Diggler, a remarkably “endowed” porn star recalling the idol of P. T. Anderson himself (along with endless movie-goers, I should add), John Holmes.

Todd Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine (1998) staged the glam rock scene of the same years and the David Bowie icon (in the character of Brian Slade, interpreted by Jonathan Rhys Meyers), as construed through the research of a journalist (Christian Bale) who was growing up at the time of Slade’s heyday; an inquiry which turns out to be a self-investigation and self-(re)discovery.

Bill Condon’s Gods and Monsters (1998) told the last days of Frankenstein queer director James Whale (superbly interpreted by Sir Ian McKellen), and his meeting with straight young gardener (Brendan Fraser), who models for him in sittings that turn out to be mutual self-confessional sessions, a queer legacy bequest on the naïve gardener, and the basis for a “scientist vs. creature” final understanding and redemption (“friend?”).

Tony Kaye’s American History X (also released in 1998) had Edward Norton as a neo-Nazi skinhead ending in jail for the brutal killing of an African American; his younger brother (Edward Furlong) idolizes him, until his teacher assigns him the task of writing an essay on his role model—fittingly entitled “American History X.” The essay appropriately turns into an epiphany, an essay in (auto)biography as well as in American history; by writing his brother’s biography, the Furlong character writes and understands himself, filling that “X” with himself, his brother, and his father’s ominous legacy of racism and hatred. All these pictures were elegiac movies about stars, in fact, and about fandom; they all made the biopic genre the site for the parallel writing of both the star’s biography and the fan’s (the journalist’s, gardener’s, film-maker’s, sibling’s) identity and self-understanding.

It was when I met Victor, and I started working on the C.A.M.P. reissues, on the interview and his memoirs, that these movies started acquiring a particular taste; the taste of self-recognition. These movies joined the detection script of the Bronski purloined author tale I reported above, to my own script of serendipity, my own story of unexpected friendship, and mutual (self-)knowledge. In these four movies, different generations meet, and biography spurs a double autobiographical process, in the older as well as in the younger generation, valuing the diversity and differences it establishes as mirroring images.

I love to think that this book, Spine Intact, Some Creases—a witty and exuberant tale of A Thousand and One Knights, flitting blithely from tale to tail, in one era and out the other, alternately hilarious and touching, instructive and impassioned—was born in a similar vein and spirit.

When I met Victor, he had retired to San Francisco, and he hadn’t written a book for fifteen years. In a way, it was when he realized that Jackie Holmes might be back to the bookshelves, that he started writing these memoirs, so that the undercover star author might join its undercover star character on the same shelves. In working with Victor, I myself was reading on the queer pulp scene, and I learnt about the chapter of American History, that was being written by cultural historians, and by pulp protagonists; a chapter in Victor’s history and increasingly, to some extent, in my own.

By collecting his tales and experiences, checking dates and names, tracing pictures and editorial information, we were staging a queer college (self-)writing course, one that might well be tagged “American History XXX,” dialectically engaging the pulp masters and ourselves, the children of the (sexual) revolution; a mutually self-definitional enterprise between generations, cultures, subjectivities, identity formations, sexual proclivities.

That early 1999 meeting in San Francisco opened my eyes to a whole historical treasure lying beyond the rigorous exactitude of historical documents and textbooks, a treasure made of numberless “obscene” personal stories. The imaginative wealth Victor introduced me to (“friend?”) is part of myself, now. Just as it is an endearing portion of American emotional history—the history I learnt to respect, and to love.

American History, xxx.

—Fabio Cleto, Bergamo, Italy

November 2004