Читать книгу Spine Intact, Some Creases - Victor J. Banis - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

This is not, and was never meant to be, a story of my life. For starters, I can’t imagine who would want to read that. I’m not a star or a celebrity or even (it seems to me) in any way unique, and I would probably pass out if I were even asked to be on a tv talk show.

My dreams are unique. I am the only person I know who dreams cartoon characters. I once had an incredibly torrid adventure with Bugs Bunny. You really don’t need or want to know the details, trust me, but I’m sure you will agree that it is peculiar. Another time it was Cathy from the comic pages, in company with Tom Cruise, and absolutely nothing sexual occurred, unless you count Cathy’s fainting dead away when she met him. I don’t know about you but I certainly think it unique, if not downright bizarre, that anyone would dream of Tom Cruise and not a hint of anything sexy going on. Talk about a waste of pillow time.

But those are just dreams and I don’t care how hard you pedal you are not going to get over the rainbow with nothing more than that. Dreams aside, what I am is an ordinary, upper age gay man. Yes, that does mean that like every gay person who grew up before the revolution I am at least a little bit crazy, but even that isn’t very interesting, is it? I mean, these days if you want to stand out from the crowd at all you really have to be certifiably sane, don’t you?

So when I was first approached about writing these memoirs, I asked that very question; Who would want to read them? Anyway, those who know me know that I am a very private person, almost certainly to a fault. I was frankly intimidated by the thought of focusing so much attention on myself, my private thoughts and feelings and my personal experiences. I’m embarrassed if anyone even sees me washing my step-ins, for Heaven’s sake.

I resisted the idea for the better part of two years (the idea, you understand, of writing my memoirs, not of washing my undies). Still, while I worked on other projects and tended to laundry, I became increasingly aware that I had played a part, if a modest one, in what has proven to be one of the most historically significant periods of social revolution.

How could I not become aware, when suddenly the reminders seemed to be popping up everywhere? I found my name appearing again and again in the indexes of other books dealing with the era. Writers and historians were now referring to me as a part of that history. All right, yes, someone did refer to me recently as ancient history, but you cannot keep other people from being snotty and anyway that’s probably another subject.

I began to hear with growing frequency from scholars looking into the period, wanting information from me. Book collectors and dealers sent me copies of my books to be autographed, to enhance their value; I was astonished to learn that they had “value.” Astonishing value, as it turns out. Copies of these one-time 75¢ books are now offered for sale on the Internet for as much as $175. I don’t even want to think of the rate of inflation.

And it isn’t only my books on the Internet. I was asked by the creators of an “Internet Museum” devoted to the pioneering gay magazine, Der Kreis, to provide an essay and photographs. There I am, seen in my early twenties, my middle years and in the recent present, so you can watch me age before your eyes—but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

A local businesswoman and gay history buff, Audrey Joseph, offered the San Francisco Public Library a five thousand dollar donation to do an exhibit of my work in the new main library then nearing completion. That is to say, my literary work. There are some of my talents that have really never been documented. Anyway, I nixed that idea when the library’s price got up to twenty thousand—minimum donations?—but it was flattering to say the least.

By the late nineties at least two different companies were issuing postcards, address books, and other such paraphernalia, with reproductions of the covers of my books.

Michael Bronski dedicated his book, Pulp Friction (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2003), to me—along with three other writers—for “(pioneering) what we now call gay and lesbian literature.” High praise indeed from one of the gay world’s top historians and chroniclers.

Students at San Francisco State University learned about me in their History 313 course—“The History of Sex” (which I suppose does make me, after all, an historical artifact).

I was even approached with requests for interviews in the gay press. I had done interviews in the press before, notably The Advocate, but that was at a time when my books were all over the place. By this time it had been more than fifteen years since I had a book on the shelves.

“But what am I to talk about?” I asked one would-be interviewer.

“About your contributions,” he replied.

My contributions? I had never been aware when I was living through that era that I was making “contributions.” I was earning a living and having fun—and from time to time tweaking a few blue noses and running scared for my efforts.

Still, it began to look as if I had become a cult figure in my old age. And it seemed that it behooved me at least to give some thought to what those “contributions” had been. If they had been. I sat down one day to see if I could list any.

Yes, it was true, because I had dared to portray lesbian activity in a positive light, I had been involved in one of the earliest and biggest of the anti-obscenity trials of the sixties—and that trial in itself had nudged the then nascent free speech movement forward. That was a contribution I supposed, if an indirect one.

It was true as well that, thanks to the notoriety that I garnered from the trial, I was able to persuade a number of the West Coast publishing houses, who until then had no interest in the genre, to begin publishing gay material. My 1966 novel The Why Not was the first gay fiction published by Greenleaf Classics. As a result of its success—and my lobbying efforts—Greenleaf went on to become the biggest of the gay pulp publishers throughout the sixties and early seventies. And with their track record to bolster my arguments, I was able personally to convince other pulp publishers to “go gay.” My campaign succeeded beyond my wildest dreams and launched that entire boom in gay publishing that so changed the book and social landscape of the sixties, unloosing a heretofore unimaginable flood of gay and lesbian fiction and nonfiction. Certainly, for gay people, that could be counted a contribution, couldn’t it?

Having broken the ice with The Why Not, I went on to write literally scores of gay novels and nonfiction works (and non-gay as well, I should probably point out) under my own name and as Victor Jay, Don Holliday, J. X. Williams, Jan Alexander and dozens of other names, in quantities that I am sure remain unequaled.

In addition to the American and British editions (hard and soft cover) of my books, I was eventually translated into German, Swedish, Dutch, Norwegian—even foreign language audio editions.

It was said in the late sixties, and I have no reason to doubt it, that I was at that time the most widely read gay writer in the world—or, more correctly, the most widely read writer of gay material. I hasten to say that this was in part a matter of having written large numbers of different books and not because any single book racked up such spectacular sales figures, though certainly many of them did well. By the early seventies, by the most conservative estimates, there were more than three million copies of my gay books in circulation. Mere peanuts for writers like Danielle Steele or Stephen King, but not bad for a paperback writer whose name never graced a bestseller list. More importantly, not bad for a market that only a few years earlier was thought not to exist.

I am not altogether sure, you understand, that everyone would consider that contribution a welcome one.

There was no question, however, that I had been a major factor in creating the soon burgeoning demand for gay material. To help fill that demand, I went on to train other writers and even to represent many of them as an agent. For the next several years my writers and I supplied far and away the majority of gay fiction and nonfiction being published. There was a joke going around the industry in the late sixties, to the effect that the gay publishing revolution had mostly happened around my kitchen table. It wasn’t too far off the mark, actually.

At the same time, in book after book, we continued to break down the barriers to what could be said or described in print and so opened doors to alternative themes. I was among the first to write openly and in depth about a number of theretofore taboo subjects—Men & Their Boys (1966) looked at the relationships between adult males and teen boys, and Black and White Together dealt with interracial sexuality. In various books I cast light on bisexuality, incest and homosexual rape, subjects barely whispered about then and with which many people even today remain uncomfortable. I thought, and still think, that they ought to be looked at more openly.

I published straightforward male nude photography when it was still far from clear whether we could do so legally, and while I was at it launched the careers of underground photographers like Pat Rocco and Tom Di Simone. And along the way fought often and vigorously with those who thought male nudity obscene. I was convinced that it was not.

Indeed, I believed wholeheartedly that in a free society people should be free to write, photograph, print, publish or read what they choose. History has tended to agree with me but let it be said, history took some persuading.

I produced the first of the high quality, over the counter books containing sexually explicit photos, breaking one of the last remaining barriers to free expression. Perhaps a dubious contribution, but the jury is still out on that one, I think.

I helped launch the Groovy Guy Contest, the first of the male beauty pageants (as opposed to body-building competitions) and subsequently much imitated. Yes, a minor contribution at best. Nevertheless, Tinker Bell, if you like beautiful men strutting their stuff, this is the time to applaud.

Throughout the sixties and early seventies I brushed shoulders (and sometimes more) with many, perhaps most, of those leading the sexual revolution. I swapped gay porn and bisexual musings with Hugh Hefner, the bunny man himself, and discussed the legal niceties of sex-oriented publishing with Wardell Pomeroy, Kinsey’s one-time righthand man and ultimately his successor at the Kinsey Institute.

For twenty plus years I worked as writer, publisher, editor, agent, and writing instructor, and in all of those roles fought stubbornly (if not always wisely) for the rights of writers and publishers to say what they wanted to say, how they wanted to say it.

By the mid-seventies I doubt if there were many in the publishing world who didn’t at least know my name, though they may not always have spoken it with pleasure.

Alas, I should no doubt point out that at the same time all of this was going on I was endlessly harassed by the would-be guardians of our morals, particularly the U.S. Postal Authorities. Many of my books dealt in a positive way with homosexuals and homosexuality, which in itself made them—in the view of the Federal government—obscene and so placed me outside the law, a criminal. I was arrested twice on obscenity charges and lived for many years with the threat of arrest and prison confinement hanging over my head, and was nearly forced into exile to avoid prison. It was not altogether a glamorous profession.

* * * *

Well, I suppose those were contributions, if not all of them positive. When I turned my attention to that period in time, I was surprised to discover that so much of it, in particular the publishing revolution of the era, of which I had certainly been a part, was so poorly documented. Not that there had been nothing published on the subject. Indeed, there were some very fine books and articles available. But everything of consequence that had been written had been written by East Coast writers for East Coast publishers, and critiqued by East Coast critics—when in fact that publishing explosion had been primarily a West Coast phenomenon. I found nothing of consequence that did not share that bias; which is to say, nothing that told the whole story.

It began to seem to me that perhaps I ought to share my experiences with those others who were interested in the era. And quite frankly I realized that if I were going to do so, it needed to be sooner rather than later. Already names and dates were fading from my never-very-perfect memory.

I sat myself down before the word processor and began to type, with reluctance at first but with more enthusiasm as the pages went by. Not that I was any less concerned about my step-ins; but it was an exciting time that I was describing and reliving it turned out to be more fun than I had imagined. What began as a chore became in short order a labor of love.

When my friends at Bolerium Books of San Francisco, Mike Pincus and John Durham, originally asked me to do this for them, it was meant to be something in the nature of a pamphlet to be distributed through their mailing list and on their web site. It soon became evident that there would certainly be more than a pamphlet. Well, I couldn’t have written all that stuff if I hadn’t been wordy, could I? Anyway, I am particularly grateful for their generosity in letting me develop their idea for someone else.

I have written this more or less as it occurred to me, without strict allegiance to time sequences or any sort of logical structure—more as if I were sitting chatting with the reader. You may find it helpful to read it in a corresponding manner. So far as that goes you don’t have to read it at all. That’s the nice thing about freedom, it works both ways.

For the most part I have tried to tell the story of the revolution of the sixties and seventies, though for the sake of historical perspective I have written as well about the earlier years; the early sixties, the fifties and, to a lesser degree, the forties.

The story I have told, however, is a personal one; the era as I experienced it. Which is to say, it is not the history of the sexual revolution that occurred then, which it seems to me yet remains to be written, nor of the companion revolution in publishing. But it is a small bit of that history and I can only hope it will provide a glimpse or two of what happened and what changed in those ten or fifteen years.

I hope too that you will find it interesting. I certainly did, both living it and reliving it. Although I said at the beginning that this was not the story of my life, I could hardly write about my experiences without sometimes talking about myself and how I came to be who and what I was, so, yes, some of my life pops up here and there; but you expected that all along, didn’t you?

It is, as I have indicated, a discursive work, and some of the subjects I touch upon will no doubt seem arbitrary and certainly peripheral to the main theme. Since I wrote at length, for instance, on my success in teaching other writers, it seemed to me that I should give some idea of how or what it was that I taught them. And since I wrote what I can now see was a rather large if uneven chapter in the history of gay fiction, I felt qualified to offer my opinions on the subsequent state of gay fiction. And after that I thought, “What the hell?”—and threw in some sleazy gossip and a few diet tips because, let’s face it, those things sell better than history.

Soon enough, however, I began to worry that I might have left myself open to charges of venality, so to be safe I added my thoughts on religion and the soul. Hmmm. Better, surely. No one could accuse me now of prostituting my art.

But then I got to thinking about those diet tips. Anyone who sees me on Oprah will know at a glance that diet tips are not my strong suit. So to offset that, because I didn’t want to come across hypocritical, I added some recipes, good fattening ones that would be more in keeping with my image. Or at least more in keeping with my figure.

And after that…but the point is, you can see that things get away from me. Which really is the story of my life, although I realize I promised at the beginning that this wasn’t going to be that.

I have made free with my opinions on all of these matters but they are only my opinions. I have also been cavalier in ignoring, where I chose, the thoughts or positions of others on the same subjects. You may object all you want. This is a personal expression. If your objections are particularly vehement or you think your diet tips are better than mine, you can always write your own book and leave my coattails alone—or as an old friend used to say, “Get off the runway, Rose, it’s my turn.”

This is a work of nonfiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is probably unavoidable.

* * * *

I have written, in addition to verse, short stories and articles, well over one hundred books. The best estimate I can make is somewhere around one hundred and forty. This, however, was far and away the most difficult writing I have ever done, for the very reason that it was so personal.

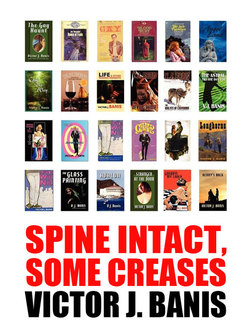

The only easy part was a phrase that I ran across in a book collector’s catalog, describing the condition of a particular book offered for sale; “Spine intact, some creases.”

“Little book,” I thought, “I know just how you feel.”

And dog-eared, too.