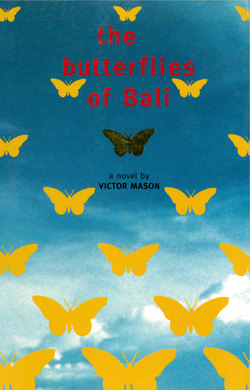

Читать книгу Butterflies of Bali - Victor Mason - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter I

A Curious Encounter

I CAN NO LONGER recall the exact date, but I retain the most vivid recollection of my first encounter with Hector.

It was on the night known as tilem, the name given by the Balinese to the black night which falls every thirty days or so between the old and new moons. The night of the black moon. Only the sounds of night and nature penetrated the potent stillness of the air; creaking of crickets and croaking of frogs, and intermittent hicket of the scops owl; and always the swish and gurgle of running water, and distant dinning of the dogs.

Descending the first short flight of steps in my path from paddy-field to main irrigation artery, I became on a sudden aware of another noise, quite apart from the nocturnal chorus and distinctly preternatural in quality, which seemed to emanate from the stream below. Its author was clearly human and in a condition of some discomfiture, since it consisted in a string of spluttered expletives and guttural interjections, the like of which I had seldom if ever heard before. I directed the beam of my flash-light to the source.

Floundering, half-immersed in the turbid flow, on hands and knees before me, was the figure of a man, clad in off-white shirt and gray trousers, seemingly somewhat the worse for wear. I hailed him;

“Hullo there! Do you want some help?”

The thrashing ceased, and upturned face peered, squinting in the light towards me. There was a discernible pause. Somewhere behind me, I could hear the scops owl call.

Then:

“Bloody hell no!” came the sputtered response, “I’m perfectly all right. But give us a hand anyway, would you?

The apparition held out a dripping palm, whilst I knelt down and leant over the steep embankment to proffer mine. The next thing I knew I was sitting in the water beside him. My torch must have fallen in with me. We remained there, motionless, in the swirling current and impenetrable inky blackness—I, in aggrieved and stony silence: he, choking with uncontrollable laughter. At length he calmed himself, then addressed me with no show of sympathy whatever.

“You clot!” he simply said, “what on earth did you do that for?”

“I was only trying to help,” I offered feebly. And as I spoke, it occurred to me that I ought to be enraged and that I should express myself accordingly. Yet there was nothing unkind or even condescending in his manner. In fact his next remarks failed altogether to surprise me.

“I know you were,” he said. “I think I must be a bit stoned,” which was merely stating what was manifest. “Since I don’t know you,” he continued, “I’m sure you will not object if I apologize. You really are a good Samaritan. Now, if you haven’t had dinner yet, perhaps you would care to join me. What do you say?”

I have forgotten to mention that I was in fact on my way into town for a meal at the time this never-to-be-forgotten incident occurred. So I assented readily to the proposal of this peculiar, unknown man. But first I needed to extricate myself—and my flash-light—from the stream; further, being soaked through, I required a change of clothing. Luckily I soon found the torch up-ended in the mud, and miraculously it was still shining. I scrambled up the bank, preceded by my host who was already marching off into the night and appeared to have made a most remarkable recovery.

“Look here!” I shouted after him, “I’m soaked to the skin: I must go home and change.”

“So am I,” he rejoined: “who cares?” Already he was halfway down the long flight of steps leading to the main road. There was nothing for it but to follow. I found it hard to keep up with him. He strode ahead at a furious pace.

“How on earth can you see where you’re going?” I ventured.

“Well obviously I can’t all the time,” came the equally obvious reply. “Papaw’s the stuff,” he added mysteriously.

Presently we came to a sign which bore the legend: Beggars’ Bush—Bar & Restaurant; and, not pausing for an instant, my companion darted up more steps and disappeared through the portal of the establishment. And I, paying no further mind to my sodden and dishevelled state, followed suit. Eventually, having tracked him down at the bar, I was more than ready to accept the glass of beer, freshly poured, that was thrust towards me at the instant of my arrival.

A couple of beers later, still dripping, we proceeded to the dining-room, where an excellent meal was served together with a first-rate bottle of wine. I remember we talked about this and that, most of it inconsequential, and I detected a certain reticence on the part of my new-found companion to declare anything at all concerning himself, beyond the fact of his first name being Hector and that he was in Bah for a brief sojourn in the course of a world tour. It was his intention to visit some of the Indonesian islands lying to the east of Bah, before going to Australia; but he was in no hurry, ungoverned by ordered time-table or itinerary. The only other thing one could point to with certainty was that he was unmistakably British. More accurately, he was what some chroniclers and librettists refer to as an Englishman.

During the course of our conversation, he let it be known that he had been born, more by accident than by design, in England where he had also been brought up and educated. Evidently he had spent little enough time there subsequently, although his family still possessed a crumbling pile of masonry surrounded by a park, somewhere in East Anglia. As for himself, he had no ties and owned nothing, he maintained: all he demanded was freedom of movement and the right of access. When I asked Hector what he did for a living, I was made immediately aware that I had committed a gross impertinence.

“I am not a businessman,” was all he would vouchsafe to me.

How shall I describe him physically? I am not adept in conjuring up mental images of people. In Hector’s case the difficulty is compounded by a universality of physiognomy, rendered all the more indistinct by a lack of irregularity and an unfailing blandness in manner. If there was one feature that could be considered arresting, it was his eyes, which were narrowly set and powerfully intent, and which ranged according to mood from penetrating gray to a mild fulvous brown. His face, clear-cut and clean-shaven, was thin; his skin pale, yet habitually tanned by the sun. His fairish hair he wore unfashionably short, parted high on the left side, one stray lock invariably falling across jutting furrowed brow.

Like Hector of yore, tamer of horses, he bore an immemorial look.