Читать книгу Butterflies of Bali - Victor Mason - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter V

The Temple on the Cliff

WHEN I AWOKE the sun was already high in the heavens, and there was no denying that I felt a bit grim. The realization that today was the last day of my vacation, and that my presence was expected in the nether regions, brought no consolation. I had barely enough time in which to prepare for my departure and organize transport to the coast, let alone become involved in such diversions as observing birds or penetrating caves and a labyrinth of flooded subterranean passages.

I wondered whether Hector and Hermione had decided to go off on their own. The awful truth was that I had no recollection of any discussion we might have had following dinner at the Beggars’ Bush, and I retained but the vaguest memory of making my fond adieux later outside the premises, and of holding Hermione ever so briefly in my arms while bitterly reflecting that our time together had been so short, and that there could be no guarantee of our meeting again within the foreseeable future.

It was with a heavy heart that I set off in my hired motor-car soon after midday, my thoughts occupied with the divine Hermione and her flashing smile and the part she had played in our adventure together. All the same, I felt reasonably certain that I should see her again, and we had exchanged addresses, promising to get in touch with one another on her return to England. But that might not be for many months hence, since she planned to accompany Hector on his travels through the Indonesian Archipelago, before arriving in Australia where they intended to visit relatives who were farming in Victoria.

The sun-drenched countryside swept by, terraced fields in every stage of growth, some fallow or flooded awaiting the new planting, others ripe for the reaper’s sickle; bound on all sides by lush green curtains of vegetation, where nestled the dwellings of the inhabitants of this fabled isle. Here and there stood flocks of snowy egrets, fossicking for eels and frogs, while overflying the fields were hosts of little swiftlets mingling with the swallows in their constant round of seeking out small insects in the air.

Burdened with my introspection, I paid little enough attention to the idyllic landscape, sculpted by one hundred generations of villagers whose livelihood was the land and its productions. As we passed the last strip of open cultivation by the shore, I beheld a squadron of frigate-birds cruising in formation above the coastline; but even the sight of these magnificent creatures, sailing on the wind, huge angular wings seemingly inflexible and motionless, failed to lift me from my despondent state.

Presently arriving at my hotel, a small complex of thatched pavilions, set in a botanical treasury of variegated beds and borders, and sheltering in a grove of coconut palms, I was shown to my room situated ten yards from the beach. A few minutes later found me installed by the beach-side bar, awaiting the arrival of my luncheon party.

By the time the fourth aperitif appeared before me, without a sign of my intended companions, I began to feel morose, if not a trifle out of sorts. Where the devil were they? The arrangements had been perfectly clear; the time of our rendezvous precise—12:30. It was now 1:30. Having telephoned around the town with no result, and once more drained my glass, I was really rather cross. How damned inconsiderate to keep me waiting like this, when I could have been so much more profitably employed! Doing what? For a start, I could have been exploring secret passages with Hector and Hermione.

Hermione, ah! The thought of her produced a pang, or rather accentuated it, for my last lingering look at her departing form had occasioned an access of despair, which had weighed heavily on my spirit ever since. Hermione! Her flashing teeth, her floating hair. Her eyes. Could I not recall their colour? At once gray and violet, as the hazy outline of Bandit’s Island on the far horizon, enveloped in mist and mystery. There was a place I should care to explore. But for one or two brief landings and a circumnavigation, and what little I had managed to glean from the literature, I knew practically nothing of this remote and rugged tract of coral outcrop, which had in earlier times served as a penal colony to the kingdoms of Klungkung and Karangasem. Sparsely populated and clothed with vegetation, and lacking surface water entirely, it was one of the most inhospitable spots imaginable. Searingly hot and dry, a land benighted in perennial rain-shadow, Nusa Penida (for that was the name by which it was known to the Balinese) had no potential as a touristic destination; and to me that was the greater part of its attraction.

It was rumoured (and I had read somewhere) that the island was a kind of catacomb—a honeycomb of caverns and black corridors, carved by both Nature and the hand of man, or giant maybe. I had heard tell of stupendous underground cathedral-like formations, whose aisles and transepts led to apse and private chapel and other secret recess; where the local populace was wont to hold its feasts and ceremonies; and where; through a network of cloistered passage-ways, the villagers might wander at will beneath the desiccated surface, safe from the roving packs of rabid dogs and scourge of blistering sun. There existed a tunnel, it had been suggested by certain wise and holy men, which linked the vassal islet to its neighbouring larger mass, below the sandy bottom of the intervening sea. Not that it was beyond the bounds of plausibility, I reflected now as I so often had before, given the porous nature of the rock and the incidence of subterranean volcanic activity; but just assuming it were so, that one might actually walk the intermediate distance of seven miles or so beneath the sea, such a journey would represent a hazardous undertaking, as perilous a venture as any devised by Homer or Verne, and requiring months of careful preparation as well as heaps of respiratory and other specialist equipment. It was certainly not an enterprise to be embarked on by one person alone. My thoughts turned again to noble Hector and Hermione. Would that we could do it together.....one day. Though that day might be long in coming. My mood remained sombre.

It was almost two o’clock. Something must have happened to prevent my friends from joining me. I wondered whether I should order a bite to eat, though to tell the truth I was not in the least bit hungry; or perhaps I should have another drink, but this did not seem a particularly good idea. I gazed ruminatively, across the troubled waters of the Penida Strait, at the violet hulk suspended betwixt sea and sky. The line of chalk cliffs glinted dully, ending abruptly in severed stacks which reached sheer from the ocean swells. They reminded me of the white walls of the South Downs of southern England. I had seen this view before exactly, looking out over the Solent to the Isle of Wight. How closely the vast slabs separated from the headland resembled the famous Needles. The realization was made less welcome by the succeeding thought that in a few hours I should be winging my way toward the latter. Away from the island of Bali, and away from Hermione.

At that moment I became aware of the perfumed presence beside me, and turning simultaneously in my seat, I saw with a tremendous start none other than the precious object of my reverie before me.

I gaped incredulously, no sound issuing from my lips, and two or three seconds must have elapsed before I managed to blurt out, “Heavens! Hermione! What on earth are you doing here? I was just thinking of you.” Heavens indeed! What was I saying?

Smiling wickedly, she parked herself on the chair next to me and tapped my arm. “I couldn’t let you go off like that. In any case I was dead bored up there on my own. Hector was keen to return to the cave, but I decided to give it a miss today and come and see you instead. By the way,” she added tangentially, “haven’t you had any lunch yet? I thought I should find you tucking into a huge feed with your chums.”

I explained how I had been stood up by the others and was deliberating on whether I should or should not eat at precisely the moment of her arrival. My appetite had suddenly revived.

“Well that’s settled,” said Hermione; “we shall have lunch together, and if the others show up, they can join us.”

“Shall we eat here?”

“Why not?”

The whole complexion of the day had changed. I felt at once more vibrantly alive.....and ravenous. Now I was delighted that my luncheon party had fallen by the wayside, and I fervently wished it would fail to recover. So we sat at a table on the beach, and ate and chatted late into the afternoon. Everything was perfect, and I was enraptured.

And then I suggested that we take an excursion to the southern tip of the island—to the cliff-top temple at Ulu Watu, perched high above the rolling breakers of the infinite Indian Ocean, dashing eternally at its foot and shaking its very foundations with a hollow roar.

To the temple known as Pura Luhur, one of Bali’s holiest where, one thousand years ago, the pioneering Brahmanic divine, Pedanda Wawu Rau, had accomplished moksa ascending to heaven in a puff of smoke, it was agreed that we should go.

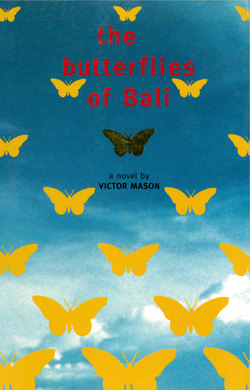

Gaily we drove along the narrow, cratered road, between high hedges of cactus and lantana, ablaze with clusters of scarlet and orange flowers, and covered with spotted blue and tawny black-veined Danaid butterflies. In dancing clouds they fluttered as we swept past. How very different was the landscape here: it seemed indeed that we had journeyed none too gently, but with a palpable jolt, from one geographical zone to another—from the Oriental to the Australian Region precisely, at one fell swoop. Here were no palms sheltering terraced rice-paddies, but stunted, thorny shrubs and eucalypts, with here and there a towering cotton-tree, affording little shade to the slopes of jagged coral scree and plots of sparse dry cultivation. Once this land must have been thrust up by violent seismic upheaval from the ocean depths: not perhaps so very long ago. From our vantage at the height of this table-land or bluff, we caught occasional glimpses of the surrounding aquamarine sea. Although it was late afternoon, the light and colour had shed none of their intensity. Everything was brighter here. The sun beat fiercely down.

“You know what this reminds me of?” Hermione suddenly turned enquiringly to me, as we bowled through the unexpected, unfamiliar terrain: “it reminds me for all the world of Corsica. It has that same quality of light, and that rugged, untamed look about it. The few people we’ve seen also have a sun-burned, swarthy complexion not unlike Mediterranean fisher-folk.” And I could not help but agree.

We passed through a straggling village of houses crudely constructed of limestone blocks, hewn from the hillside nearby. These were the only habitations we had seen. A contrary blaze of violent magenta bougainvillaea sprang over a drab compound wall, imparting a spark of life to the overpowering dereliction. Here were no wayside stalls serving drinks and confections, and providing a venue for neighbourliness and idle gossip. A knot of ragged, wild-looking individuals squatted by the roadside, staring menacingly at passers-by. From Indra’s garden we had moved to another sphere. One keenly felt the alien nature of this place.

As we drew near our destination, the countryside around us assumed a still more rugged aspect; strangely sculpted coral knolls poked through a dense undergrowth of dwarf acacia and spiny Zizyphus; here and there yawned cavern mouths. A steep descent and hairpin bend brought us to a shady parking area, situated a few minutes’ walk away from the eminence on which the temple stood, at the head of a timeless rock-cut staircase and avenue of fragrant white jasmine, as a shining throne or diadem atop a marbled citadel, adorned with wreaths of flowers. The effect on us both was awesome.

Entering the outer gate and quadrangle, we were overwhelmed in turn by the austere simplicity of design, and the silence and utter solitude of the enclosed space. It was the perfect foil and understatement for the scene that was to come. For passing through the coral portal to the inner precinct, we were in one breathless instant assailed by the blast of rushing air and the roar of surf pounding the promontory beneath our feet. We stood transfixed and mute, Hermione and I, consumed by the might of this elemental display; mere specks of form in time and space. There was no one else within the walls: we might have been the last inhabitants of planet Earth.

Holding Hermione’s hand, I steered her towards the low parapet encircling the court and scattered shrines, and together we gazed out, over the even lines of rollers receding to the sharp horizon, and finally below where the massive breakers dissolved in broad bands of churning foam, racing to meet the foot of the towering chalk cliffs. A lone tropicbird sailed by, white suffused golden, ethereal, immensely long tail-streamers floating behind and of such delicate appearance that they seemed certain to sever. And lost in contemplation of this aerial splendour, etched against the cresting waves, I suddenly saw what I had hoped to see, briefly outlined and uplifted in the translucent swell, for once free as the bird above it—a turtle.

“Look,” I squeezed Hermione’s arm, “a turtle!” These were the first words either of us had spoken in a quarter of an hour. But the wave had peaked and broken in the time taken to pronounce them, and the beast was submerged in a seething cauldron of froth.