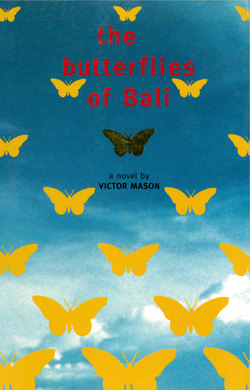

Читать книгу Butterflies of Bali - Victor Mason - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter II

Hector

IT WAS NOT SO MUCH the circumstances of my introduction to Hector as the sheer presence of the man that made such an indelible impression on me. Nowadays one refers to so-and-so as having charisma, usually someone in the limelight, such as a pop-star or politician, most of whom would seem to attract a captive band of adherents, and must therefore have and exercise this quality to some degree, whatever it may be. I am unsure of the term, and its currency is far from precise. I tend to think that the aura attending the person of Hector was more peculiar and elusive, if not unique; and I was not alone in appreciating and being affected by it. To put it plainly, I would say he was a genius, which handle may be seldom employed and must be treated both circumspectly and advisedly. There is no doubt that he had a singular talent for causing one to gasp and stretch one’s eyes that predisposed him to popular acclaim; but he was not in any sense an exhibitionist. Furthermore, his tutelary spirit, albeit beyond belief benign, was apt to lead him astray on occasion.

I could also have mentioned that other attribute by which he excelled, as catalyst—catalyst in the sense of bringing people together quite haphazardly in certain situations, if not actually working any fundamental change in the individual or collective psyche.

It was this latter quality that became apparent the very evening of my involuntary immersion in the stream. For I noticed during our dinner that a number of guests exchanged civilities with Hector or nodded in his direction. And afterwards when we adjourned to the bar, it seemed to me that he attracted quite a crowd around him: it was not as if he in any way physically compelled their presence, or even actively encouraged or acquiesced in it. They simply happened to be there; and, as I recall, a good time was had by all.

As we chatted in the snuggery, I also had occasion to observe that Hector was a more than competent linguist. He spoke rapidly and (to me) unintelligibly in fluent Spanish and French to those who expressed these languages as their mother tongues, and he owned more than a smattering of the local lingo, which could be inferred from his frequent and summary demands of the barman. The promptest service was preceded by only the one request.

He displayed also a considerable knowledge of music, most notably of the vintage jazz that regaled us for the best part of the evening, played, I might add, on an ancient gramophone at the behest of the landlord, another Englishman with whom Hector evidently enjoyed more than a nodding acquaintanceship. But the highlight of the proceedings was unquestionably the musical performance of which Hector himself was the author.

The establishment boasted a battered old upright piano. Now it is axiomatic that whenever a piano is installed in a public place, there will be a host of budding musicians and others imbued with artistic pretensions to play it.

For an appreciable while, some fellow had been plinking ineffectually, if unobtrusively, in the background, trying to follow the recorded orchestrations relayed by the gramophone. At length he gave up and resumed his seat by the bar, an air of resignation defined by his every movement. It had been a hard act to follow. We were listening to the first Victor recordings, cut in 1926, of Jelly Roll Morton and his Red Hot Peppers, intricate ensemble music, punctuated by breathtaking breaks, and played by New Orleans musicians in the grand New Orleans manner.

There came a lull in the programme provided by our publican. At the time I was deep in conversation with a Canadian couple whom I had met previously, and who, like me, professed a keen interest in birds. I was only dimly aware that the music had stopped, and then started up again. Unmistakably, it was still Jelly Roll at the keyboard, but this time in solo performance. I could claim a certain familiarity with both the composition and its rendering, for I had always been a Morton fan and kept practically all his discs in my own collection.

Yet I detected a subtle difference in timbre and execution, which struck me as odd; indeed so odd that I thought I would make mention of my discovery to Hector. On turning to address him, I found his seat vacant. And then I had the shock of my life, for I saw in one blinding flash of recognition that, quite unbeknown to me, Hector had exchanged bar-stool for piano-stool: it was he, not Morton, who was now the founder of the feast.

To say that I was entranced would be to understate the case. I passed the rest of that soiree in a state of total exaltation. He played beautifully, and, I must say, with great originality. His was no slavish imitation; everything he performed was his own highly individual interpretation. Apart from one or two numbers derived from other jazz masters, it was mostly Morton; but there were tunes of his own composing which would have graced the repertoire of Mr. Jelly Lord himself. He even came up with one perfectly spontaneous piece, which he entitled Beggars’ Bush Bumps and dedicated to the landlord’s lively and luscious Balinese wife.

After playing for two hours or more, Hector declared a halt and his intention to have one for the road. I congratulated him on his virtuoso recital, and although he evinced only a characteristic modesty, I had the distinct impression that my appreciation of his output pleased him no end.

My enthusiasm had touched him. That much was evident. There existed already between us that bond which unites the devotees of any idiom; and although I lacked Hector’s musical faculty, we shared an affinity for classic jazz and for what is considered to be classical music in general. As I was later to learn, Hector could recreate the compositions of Morton and Chopin with equal facility—his two favourite composers he maintained. He had that God-given gift of being able to reproduce, after one hearing only, any melody or set-piece note for note. Having perfect pitch, he played everything by ear. As to scored arrangements, he was unable to read a note.

“Thanks for being such good company and rescuing me from the flood.”

“Really it was nothing. I thank you. And I loved the way you played: simply marvellous.” We were standing at the foot of the steps, under the sign of the inn, and it was time to go our separate ways. But before our parting, another revelation was at hand.

“You’re keen on birds, aren’t you?” Hector announced and enquired. “I’m fairly keen myself,” he went on, “although I must admit I’m not as well versed in the local avifauna as you.”

That shook me, I can tell you. Not everyone talks in terms of avifauna. And while I may have mentioned birds en passant at the table, I had deliberately refrained from revealing my passion for the subject. It is very boorish to inflict one’s specialities on perfect strangers, unless previously apprised of their personal interest. Possibly Hector had overheard a part of my discussion with the Canucks. I hardly knew how to respond; so I let him continue.

“Tell you what,” he proposed unexpectedly: “why don’t we slope off for a bit of bird spotting in the next day or two, provided of course that you don’t have something better to do?”

I assured him that nothing would please me more, and that I was ready when he was. “I’m as free as a bird,” I said.

“Great! Well that’s settled. How about tomorrow?”

“Suits me fine.” So it was arranged that we should meet the following day at noon, on the selfsame premises.

“First we’ll have a bite and sup,” insisted Hector, “before setting off in search of the rara avis.”

And as he pronounced these final words, it occurred to me that I might have already found it.