Читать книгу Japanese Art of Stone Appreciation - Vincent T. Covello - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

Characteristics and Aesthetic Qualities

Apart from the suiseki’s aesthetic qualities, the collector is initially concerned with the size and hardness of the stone. The test for size is only approximate: the stone should be larger than a jewel or pendant but not too heavy for a person of average strength to lift. Anything larger is considered to be an outdoor garden stone (niwa-ishi). Miniature suiseki—stones smaller than 3 inches high and 3 to 4 inches wide—are seldom less than 1½ inches high (Fig. 35); large suiseki are rarely more than 12 inches high, 24 inches long, and 12 inches wide. Within this range of sizes the most valuable stones are those that are hard and firm. Soft and lightweight volcanic or sedimentary stones have traditionally not been used, although in recent years they have gained in popularity.

Having selected a stone of appropriate size and hardness, the collector is primarily concerned with the stone’s aesthetic qualities. Does the stone have an interesting color, patina, and texture? Is the shape balanced and harmonious? Are there obvious faults or structural defects? Does the stone suggest a distant peak, an island, or some other object associated with nature? What emotion does the stone arouse? Is it one of tranquillity and serenity or one of striving and anxiety?

By asking these questions, the collector is seeking information about three interrelated aesthetic qualities common to nearly all traditional suiseki: suggestiveness, subdued color, and balance. The collector is also judging whether the stone possesses wabi, sabi, shibui, and yugen—four closely related Japanese aesthetic concepts with no direct English equivalents. Their meanings will be discussed later in this chaper.

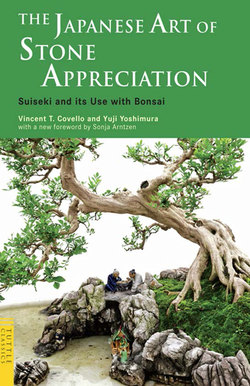

Fig 7. Near-view mountain stone. The shape of the stone suggests the mountain scenery shown in Figure 36. Height: approx. 4 inches (10 cm.). Place of origin: United States (California).

SUGGESTIVENESS

The beauty of a suiseki is derived, in part, from the power of the stone to suggest a scene or object (Figs. 7, 36). For centuries collectors have searched for stones that excite the imagination. Prior to the nineteeth century the most admired stones were those that suggested a mountain set in a lake, or an island in the sea. By the twentieth century, however, Japanese tastes had changed, and virtually any naturally formed stone that suggested a natural scene or an object associated with nature could be given serious consideration.

The suggestive possibilities of suiseki are almost limitless. The stone can transport the viewer to a lonely, abandoned thatched hut by the sea, or to a world of snow-covered mountains, hidden valleys, alpine meadows, austere mountain passes, desert plateaus, cascading waterfalls, windswept islands, hermit caves, clear mountain lakes, or storm-battered cliffs. Alternatively, the viewer may see the beauty of a delicate flower eternally frozen in the stone.

Today, as in the past, suiseki are often given names which express the suggestive qualities of the stone. The names of some well-known Japanese stones are “Snow-Covered Cottage,” “Moon over the Rice Paddies,” and “Twilight Clouds.” Suiseki are also frequently given names that express a poetic or emotional sentiment, such as “Stillness” and “Elegance.” The name given to a suiseki may, in addition, evoke literary, musical, artistic, philosophical, mythological, or religious associations. Some illustrative names of American suiseki, for example, are “Mona Lisa,” “Shangrila,” and “Four Seasons.”

Paradoxically, it is often the case that the simpler the stone, the greater its richness and expressive possibilities. The highest-quality suiseki are not exact copies of natural objects; in accordance with the Zen-related preference for simplicity, the best stones capture the essence of the object in only a few simple gestures. By presenting only a suggestion of the object, by expressing more with less, such stones stimulate and challenge the imagination, enticing the viewer to complete the picture.

Suggestion, being both ambiguous and subjective, depends in large part on the willingness of the viewer to admit a deeper beauty in the stone. Drawing on each individual’s unique experience and ability to go beyond literal facts, a single stone can evoke a variety of associations, interpretations, and responses (Fig. 37).

SUBDUED COLOR

The color of most traditional suiseki is somber and subdued. Stones of deep color—especially black, gray, or the more subdued shades of brown, green, blue, yellow, red, and purple—are generally preferred to those that are light in color. Crystals and stones that are pure white have traditionally not been selected. Most collectors feel that crystals have a superficial charm that is distracting, and that pure-white stones lack character, interest, and depth.

Color is a vital element in the suggestive power of a suiseki. The color of a stone may evoke the image of the first green tender leaves of spring, the blue of a crystal-clear day in the mountains, the scarlet and crimson colors of autumn leaves, the soft gray of a morning mist, the pastel colors of the breaking dawn, or the pale pink color of a winter twilight reflected on a mountain glacier.

The most prized suiseki are those that possess a blend of subtle colors. The colors arise from deep within the stone, as if illuminated by a hidden light source. Each color veils the one beneath, creating an effect of age and mystery.

The beauty of a stone can be considerably enhanced by a subtle patina, and by deep patches of green or black suggesting cliffs and caves. To encourage the formation of a patina, some owners water their stones several times a day and store them in partially shaded places. Many collectors spray their stones with water to enhance their color while on display. Wetness brings out subtle surface tones; it also deepens the color and produces a more aged appearance. In order to achieve the same effect, many collectors frequently touch their stones, thereby transferring body oils to the stone’s surface.

Fig 8. Distant mountain stone illustrating the interplay and harmonious balance of opposite yet complementary aspects. Place of origin: Japan (Kamogawa, Kyoto).

BALANCE

Balance is an essential element in the beauty of a suiseki, providing much of its aesthetic interest. In judging a suiseki, the collector examines the stone from all six sides (front, back, left side, right side, top, and bottom) and looks for asymmetrical, nonrepetitive, irregular, and contrasting elements in harmonious balance. These elements are especially important in choosing the “front” (i.e. the most attractive and interesting side) of the suiseki. Stones with elements that exactly repeat one another and stones that are distinctively square, round, or equilaterally triangular in shape are seldom chosen. Most collectors feel that such stones are excessively rigid and formal in feeling, and that they lack the traces of individuality that set each suiseki apart from all other stones.

Balance is created by the dynamic interplay and equilibrium of several opposite yet complementary aspects or characteristics of the stone: tallness/shortness, largeness/smallness, verticality/horizontality, convexity/concavity, hardness/softness, straightness/roundness, roughness/smoothness, darkness/lightness, movement /stillness (Fig. 8). The quality of a suiseki is determined, at least in part, by the answers given to the following questions: Do the various elements combine to form a stable and well-grounded stone? Are the various parts harmoniously proportioned? Are any triangular shapes equilateral or asymmetrical? (Preference is given to shapes that form an asymmetrical triangle.) Is there variety in the stone’s texture and in the size and shape of the peaks? Is the number of peaks odd or even? (Preference is given to an odd number of peaks if there are more than two.) Is there a pleasing balance of vertical and horizontal features? If the stone is not balanced, these varied elements will clash with one another, creating a feeling of instability and clutter. In a well-formed suiseki, asymmetrical elements combine together to create an integrated, stable, and harmonious whole.

WABI, SABI, SHIBUI, AND YUGEN

Suggestiveness, subdued color, and balance are all important qualities of suiseki. Yet the traditional appeal of suiseki is best expressed by a stone’s possession of wabi, sabi, shibui, and yugen—several highly complex Japanese aesthetic concepts closely associated with Zen Buddhism, the Japanese tea ceremony, and the haiku poetry (seventeen-syllable Japanese verse) of the famous seventeenth-century Japanese poet Basho. None of these concepts can be precisely defined; nor can the qualities they express be directly seen, for they represent a mental state felt by the viewer in the presence of the stone. Although each word conveys a vaguely similar meaning and feeling, each differs in nuance and connotation.

Wabi can mean melancholic, lonely, unassuming, solitary, desolate, calm, quiet, still, impoverished, or unpretentious. Wabi is a subjective feeling evoked by an object, the classic image being an abandoned fisherman’s shack on a lonely beach buffeted by the wind on a gray wintry day. Sabi can mean ancient, serene, subdued, mellowed, antique, mature, and seasoned, as well as lonely, solitary, or melancholic. The presence of sabi is often suggested by the patina and other signs of age or wear on a treasured antique. Shibui can mean quiet, composed, elegant, understated, reserved, sedate, or refined. The quiet and understated elegance of a formal tea ceremony communicates much of the essential meaning of shibui. Finally, yugen can mean obscure and dark, although this darkness is a metaphor for the mysterious, the profound, the uncertain, and the subtle. The classic illustrations of yugen are the moon shining behind a veil of clouds, or the morning mist veiling a mountainside.

Considering the Japanese taste for ambiguity, it should come as no surprise that these concepts are so vaguely defined. For many collectors, the multiple meanings of wabi, sabi, shibui, and yugen can only be captured through poetry. The solitary and tranquil scenes evoked by the following lines of poetry, for example, express much of what is meant by these terms.

To those who long for the cherries to blossom

If only I could show the spring

That gleams from a patch of snow

In this snow-covered mountain village

— FUJIWARA NO IETAKA (1158-1237)

A bird calls out

The mountain stillness deepens

An axe rings out

Mountain stillness grows

— ANONYMOUS (Ancient Chinese Zen poem)

The qualities of wabi, sabi, shibui, and yugen are most evident in stones with worn edges that have endured centuries of weathering, erosion, and buffeting by wind, sand, ice, earth, heat, and water. Such stones are not only beautiful in their own right, but are appreciated as symbols of endurance, solidity, stability, strength, sturdiness, and character. Yet the various accretions of time—scars, lines, wrinkles, fine cracks, patina, and rusting— also reveal the relentless workings of nature and symbolically represent the impermanence, transience, evanescence, perishability, and fleeting character of all things (Fig. 38). The stone, as solid, stable, permanent, and unchanging as it may seem, is fated to disintegrate and disappear. These contrasting yet complementary aspects of the stone make the experience of its beauty deeper and more poignant.

Stones possessing wabi, sabi, shibui, and yugen tend to be especially subtle in their beauty; thus the viewer must be sensitive to nuances and minute details: fine shadings of color, slight differences in texture, and nearly imperceptible refinements of shape. When combined with other aesthetic features of the stone, it is these qualities that distinguish a great suiseki from an ordinary one. The beauty of a great suiseki often lies modestly below the surface and must be uncovered by a discriminating eye.

Some Japanese commercial establishments and collectors use a variety of methods—grinding, chipping, cutting, painting, acid burning, and polishing—to alter the stone. Occasionally a dealer or collector will also apply a coat of matte lacquer to bring out the color of the stone. Purists feel that such alterations violate the spirit of wabi, sabi, shibui, and yugen. According to the traditionalist point of view, the stone should be left as nature made it, except perhaps for some light brushing or grinding of an uneven base. Many commercial dealers argue, however, that high-quality suiseki are rarely found in their natural state. These dealers feel that some form of treatment is often necessary to meet the growing demand for quality stones.