Читать книгу Japanese Art of Stone Appreciation - Vincent T. Covello - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Historical Background

For thousands of years the Japanese have looked upon stones with a spirit approaching veneration. It is therefore not surprising that Empress Regent Suiko greatly admired the miniature landscape stones first brought to Japan as gifts from the Chinese imperial court during her reign (A.D. 592-628). Reflecting the Chinese taste of the period, these imported stones were often fantastically shaped, with deep folds and hollows, pass-through holes, highly eroded surfaces, convoluted forms, and soaring vertical lines (Fig 2). Stones of this type were popular in Japan for many centuries and were an important item of trade (Fig. 1).

During this early period of development, miniature landscape stones were appreciated both for their natural beauty and for their religious or philosophical symbolism. For Buddhists, the stone symbolized Mount Shumi, a mythical holy mountain that was believed to lie at the center of the world. (Fig. 31). For Taoists, the stone symbolized Horai, the Taoist paradise (Fig. 32). For believers in the Chinese philosophical system of yin-yang (in Japanese, in-yo)— the ancient doctrine that attempts to explain nature’s workings according to two opposing yet complementary principles—a miniature landscape stone set in water symbolized the two fundamental forces of the universe. The stone represented yang characteristics: hard, solid, unyielding, dry, hot, bright, strong, forceful, rough, and penetrating. The water represented yin characteristics: soft, void, yielding, moist, cool, dark, mysterious, weak, passive, delicate, sensitive, and receptive.

The Japanese, appreciation for miniature landscape stones was also highly influenced by Shintoism, the native religion of Japan. For the Shintoist, specifically designated natural stones and other elements in the natural environment—the sun, the moon, and particular trees—were the abode of powerful spiritual forces or gods (kami). To symbolize the divine nature of such stones and to mark them off as places of worship, they were encircled by a thick rope of plaited rice-straw fringed with rice stalks and strips of folded white paper. A striking example of this practice is the pair of rocks in Futamigaura bay, which lie just offshore near the city of Ise on the Pacific coast of Japan (Fig. 33). For centuries these two rocks—romantically called “Wedded Rocks” (Meoto-iwa)—have been associated with Izanagi and Izanami, the male and female mythical creators of Japan.

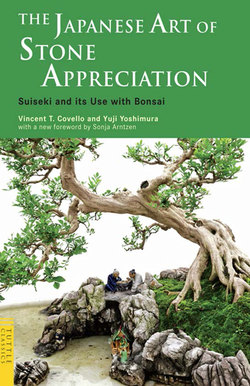

Fig 1. Section of a sixteenth-century Japanese screen entitled “Portuguese in Japan.” The screen shows Portuguese traders unloading stones and other imported Chinese goods from a ship.

From these diverse religious and philosophical traditions there developed in Japan several forms of artistic expression based on the aesthetics of stones. Miniature landscape stones set in trays were one manifestation; however, the art of stone appreciation was particularly refined in garden design. One of the earliest and most comprehensive Japanese books on the latter art was an eleventh-century garden manual called the Sakuteiki.7 It describes in minute detail the characteristics of stones and their proper positioning, advising the gardener to exercise great care in aligning them. It is warned, for example, that a stone incorrectly placed—such as a naturally upright stone set horizontally—will disturb the spirit of the stone and may bring misfortune to the owner.

Detail of screen.

Fig 2. Chinese Coastal rock stone with tunnels. Height: approx. 16 inches (41 cm.).

The artistic appreciation of stones underwent further refinement in the centuries immediately following the writing of the Sakuteiki. From the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, however, there occurred a radical change in Japanese taste, due partly to the political developments in Japan at that time. During the latter part of the Kamakura period (1183-1333), the samurai-warrior class rose to power. Active trade and cultural exchanges with China hastened the transmission of Zen Buddhism, which won quick and wide acceptance by the samurai. Under the influence of Zen—with its emphasis on austerity, concentrated meditation, intuitive insight, the experience of absolute “nothingness,” and direct communion with nature—a different type of stone came to be admired. Unlike the older Chinese stones, these new stones were subtle, profoundly quiet, serene, austere, and unpretentious (Fig. 3).

During this period of Japanese history, suiseki, as well as the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, bonsai, calligraphy, literature, painting, music, and architecture, attained new levels of refinement and perfection. Connoisseurs of miniature landscape stones would hold gatherings where participants competed with one another writing poetry about the stone on display. Stones were sometimes so highly prized that their owners carried them wherever they traveled. It is believed, for example, that the emperor Go-Daigo (1288-1339), after having failed to throw off the Kamakura regency, fled to Mount Yoshino with his favorite stone, known as “Floating Bridge of Dreams” (Yume no Ukihashi) (Fig. 4). The stone’s name is a literary allusion to the retreat from the world and sorrow of Lady Ukifune, a character in The Tale of Genji. The emperor may have named the stone in reflecting upon his own unfortunate fate. One hundred years later, in the fifteenth century, another well-known admirer and collector of miniature landscape stones was the military dictator, or shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1435-1490).

Fig 3. Human-shaped stone suggesting a sitting Zen monk or old man staring into space. The stone is named “Li Po Meditating on a Waterfall.” Li Po (Li Bo) was a famous poet of the Chinese Tang dynasty (a.d. 618-907). Originally found in China on Mount Lu Shan, Fukien (Fujian) province, the stone is believed to have been brought to Japan in 1654. Over the centuries, it has had several owners, including the literati painter Rai San’yo (1780-1832). Height: approx. 9 inches (23 cm.).

Fig 4. Distant mountain stone, “Floating Bridge of Dreams,” originally found on Mount Chiang Ning (Jiangning), Chian Su (Jiangsu) province, China, and later owned by Emperor Go-Daigo (1288-1339) of Japan. The unusual tray was originally a Ming-dynasty incense burner. Height: ¾ inch (2 cm.).

It was also during the fifteenth century that most of the great dry landscape gardens (karesansui) were constructed. The most famous of these is the garden of sand and stone located within the grounds of Ryoan-ji, a Zen Buddhist temple in Kyoto (Fig. 5). In a rectangular space approximately the size of a modern tennis court, fifteen stones of various sizes are set on moss in an expanse of carefully raked white gravel. The grayish-brown stones, arranged in five groups, are thought to have been composed by the artist Soami, although this is by no means certain. Since the creation of the Ryoan-ji garden, thousands of observers have marveled at the perfect balance, harmony, subtle tones, and mystery of these stones. For some, the stones suggest islands dotting a vast sea, or mountain peaks rising high above the clouds. For Zen monks and others, the stones were symbols of Zen thought, serving as objects for contemplation and meditation. According to the teachings of Zen, everything finite tells of the infinite, and everything animate and inanimate is the product of the same force. By meditating on the stone, a monk could understand the essence of the stone, the essence of a mountain, and all else in the universe. To experience this essence, to become one with the stone, was to become enlightened.

In order to more clearly perceive the essence of the stone, there developed among Zen monks of the Muromachi period (1338-1573) a preference for stones stripped of all distracting elements and unnecessary detail. This, in turn, led to a preference for stones that were more suggestive than explicit, more natural and irregular than artificial and symmetrical, more austere, subdued, and weathered than ostentatious, colorful, bright, and new. Reduced to its bare essentials, the stone became a means of spiritual refinement, inner awareness, and enlightenment.

During the Muromachi period, the aesthetic tastes of Zen monks strongly influenced the Japanese ruling classes. The warlord Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582), for instance, who overthrew the Ashikaga shogunate, was known to be an enthusiastic collector of both Zen-inspired garden stones and miniature landscape stones. In one incident, he is said to have sent a miniature landscape stone, named “Eternal Pine Mountain” (Sue no Matsuyama), together with a fine tea bowl, in exchange for the Ishiyama fortress (currently the site of Osaka castle) in 1580.

Another well-known collector of stones was Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591), a sixteenth-century tea ceremony grandmaster famous for his simple and quiet ceremonies. Rikyu, a strong admirer of miniature landscape stones, is believed to have introduced the custom of formally displaying a quiet and simple stone in the alcove of a tea ceremony hut. As part of the tradition, the stone is set in the middle of the display area and placed under a hanging scroll (Fig. 6).

Fig 5. Section of the dry landscape garden created in the fifteenth century at Ryoan-ji, a Zen temple in Kyoto.

In the seventeenth century one of the best-known collectors of miniature landscape stones was Emperor Go-Mizuno’o (1596-1680). In addition to being an avid collector, he is believed to have played a major role in introducing the practice of using low-rimmed oval or rectangular trays for the display of stones. Until his time, stones were customarily set in a high-rimmed (about 2 in.), black-lacquered oval tray.

Fig 6. A formal display of a simple, quiet stone in the alcove of a Japanese tea ceremony hut.

During the Edo period (1603-1867) the development of the art of suiseki was associated with the rise of wealthy merchants and townspeople, who competed with the aristocracy for the best stones. The growth of the art was also closely associated with the Bunjin, or literati, school of painting, which flourished during the Edo period. Members of this school, mainly classical scholars who followed Chinese models, freely expressed poetic sentiments through their light wash paintings of mountain landscapes. Many of the stones collected by literati painters, such as Rai San’yo (1780-1832), have been passed down from generation to generation as prized treasures and exist in collections today (see Fig. 3).

Early in the Meiji era (1868-1912) there was a brief period during which the development of the art of suiseki came to a virtual standstill. The wealth of the nobility and the samurai had declined, and the merchant classes had turned their attention to other art forms. By the turn of the century, however, the popularity of suiseki had revived, reaching an all-time high in the latter half of the twentieth century. Since 1961, for example, the Japanese Suiseki Association., in collaboration with the Japanese Bonsai Association, has sponsored annual exhibitions of suiseki in Tokyo. At Japan’s twenty-first national exhibition in 1981, 119 suiseki were exhibited, including 2 from the United States. To promote the appreciation and understanding of suiseki, several international exhibitions have also been held: the first at Tokyo’s Hibiya Park, in conjunction with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics; and subsequent ones at the Expo ‘70 Commemorative Park in Osaka, Japan. At the 1981 Osaka International Exhibition, suiseki collectors from around the world submitted photographic entries. The international status of the art was further enhanced in 1976 when the Japanese people presented six priceless suiseki to the United States as part of their Bicentennial gift. These stones are on permanent exhibit at the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington D.C. (Fig. 34).

Footnote

7 Toshitsuna Tachibana, Sakuteiki: The Book of Gardens, trans. Shigemaru Shimoyama (Tokyo: Town and City Planners, 1976).