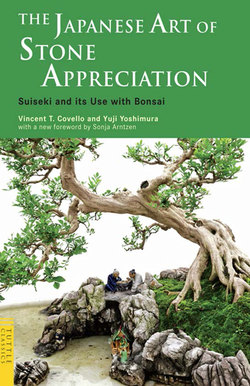

Читать книгу Japanese Art of Stone Appreciation - Vincent T. Covello - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

Who among us, when walking along the banks of a river or the shores of a sea, is not drawn to collect stones, be they small pebbles, or rocks just within our carrying capacity. The collecting itself is akin to meditation, for the preoccupations of our busy minds fade away as we focus on distinguishing the minute differences between the stones at our feet. What a moment before was an undifferentiated mass, becomes a community of individuals, each with its own marvelous suchness. Thus begins appreciation. This book is devoted to the Japanese art of appreciating such small-scale stones, known as suiseki.

As the chapter on historical background touches upon, the appreciation of stone has a long history in China, which can be dated back to pre-history and the veneration of jade. Disks and other jade objects constitute one of the important categories of pre-historical artifacts in China. The first term for special stones in Chinese vocabulary, guaishi 怪石 “fantastic stones” appears in a list of imperial tribute dating back to the middle of the first millennium B.C.1 It most likely referred to semi-precious stones like jade, but came to be the general term for stones and boulder-size rocks with unusual attributes. The term itself is instructive, however, because the Chinese taste for stone was marked from the beginning with a predilection for the strange. The prevalence of limestone along Chinese rivers and sea coasts has resulted in the natural production of stone in writhing shapes, full of hollows and holes. These twisted, verging on grotesque, forms have always been the mainstay of Chinese garden design. For more than a thousand years, huge stones of this type have been shipped from one end of China to the other for the creation of “stone forests” and “grottos for immortals.” Fortunes were spent on these enterprises and their owners fretted over the difficulty, despite the enduring quality of stone, to preserve these gardens for posterity. One of the most famous cases of this was Li Deyu (787-850) whose villa at Pingquan outside of Luoyang was legendary for its rock and plant collection. Li Deyu wrote in an exhortation to his descendents, “Whoever sells even one rock or a single plant will not be considered a good offspring of mine.”2 Yet, no sooner had he died than economic and political exigencies forced his descendents to sell off the treasures, including one of his favorites, the “Rock for Sobering Up from Intoxication.” Apparently Li Deyu used to lean against it, as though it were a servant, whenever he got drunk. Such notorious cases mark the point where petrofilia crosses over into petromania; readers of this book beware, it may be catching! I once had the opportunity to witness the arrival of a container load of Chinese fantastic boulders ranging in size from half a ton to five tons for the garden of a friend in England who is a dealer in Chinese art. He had long been seduced by the smaller scale “scholar stones” (of the type illustrated in figure 2), but he dreamed of creating a Chinese stone garden for himself. The rocks themselves apparently were not so expensive, but shipping them half-way round the world was, needless to say, a fantastic extravagance. When they arrived in Britain, the credulity of Her Majesty’s Customs’ agents was strained by the bill of lading listing the contents of the container as only “Chinese rock” and ordered a thorough check of the shipment. When it was revealed to be just what it said, my friend was still charged for the inspection on the grounds that he had “caused mischief,” presumably with such a whimsical import. Such are the dangers of petromania.

The appreciation for stone in Japan has a long history too. While it has been influenced deeply by the Chinese tradition, it also, as is pointed out in the introductory chapter, has its own independent root in the native religion of Shinto. Animistic beliefs in Shinto led to the veneration of natural stones in situ as dwelling places of spirits. Perhaps this explains to some degree why the taste in stone in Japan from the beginning has tended to a preference for the restrained and simple, a predilection subsumed under the wabi, sabi, shibui, and yugen aesthetics dealt with in Chapter 2 of this volume. It is certain that immense sums have been expended in Japan for the creation of private gardens, but such creations have not generally achieved legendary status. Even the affection felt for stones has had a more restrained character in Japan. As evident above in the example of Li Deyu, a personification of stones in China has been part of their appreciation. Here is a charming example of that kind of anthropomorphic view from the conclusion of a poem by Bai Juyi (772-846), who is coincidentally the most beloved of all Chinese poets in Japan. In this long poem, Bai Juyi eulogizes a pair of rocks in his garden and ends with the following:

Each man has his own preferences:

All things seek their own companions.

I have come to fear that the world of youth

Has no room for one with long white hair.

I turn my head and ask this pair of stones:

“Can you be companions for an old man?”

Although the stones cannot speak,

They agree that we three shall be friends.3

By contrast, traditional Japanese poetry tends to present rocks and stones simply as part of a natural landscape. Here is one example by Fujiwara no Shunzei (1114-1204),

In one place, frozen,

in another, breaking up,

the mountain river

sobs between boulders,

a voice in dawn’s light.4

There is a slight feeling of personification in the verb “sobs” but the boulders are not depicted as having human attributes. Rather than anthropomorphize the natural elements in this scene, the poet’s mind has merged with the scene. This is also evident in one of the most famous haiku on stone and sound by Basho (1644 to 1694),

Such stillness, sinking into the stones, the cicadas’ cries.5

Perhaps this long tradition in Japan, nurtured by poetry, of cultivating attentiveness to the special qualities in the most ordinary of natural scenes has contributed to a love for stones characterized by a quiet, unexaggerated beauty.

The greater part of this book is reserved for an overview of the Japanese canons of stone appreciation, as well as practical matters related to collecting, altering, and displaying stones. When I was first approached to write a foreword for this book, I was at a loss as to what I might be able to provide, given that I am not an expert in Japanese stone connoisseurship. At first, I felt that I lacked the frame of reference to fully appreciate the classification system. The next morning, however, after reading the book, I wandered out in my garden and suddenly one of the rocks I had casually gathered from the beach took on new and exciting significance. I should explain that I live on one of the Gulf Islands off the Pacific Northwest coast of Canada. The geological foundation for the islands is sandstone and shale, but over the shale beaches are strewn a great variety of stones that have been ground and polished by an ancient glacier before being dropped as the glacier receded. The stone I noticed that morning was smooth, dark gray-green, with three white lines descending its sides in a pleasingly random pattern. It came to me, of course, this is a “Thread-waterfall stone” (Itodaki-ishi) and I rushed inside to fetch the book and look it up on p. 34. There was the description and the illustration, Fig. 41, to confirm it. I derived such pleasure from this recognition, and the stone has become infinitely more precious. This experience made me reflect on the importance of classification systems to help us recognize differences among the myriad phenomena surrounding us. Naming actually enables us to see more clearly. That is what the classification system in this book did for my perception of this one stone. Now, I am contemplating ways to create a suitable display for it, perhaps improvise a driftwood stand to suggest a surrounding ocean, or find a suitable clay pot in which to immerse it in sand. All the aesthetic advice and instructions for display that I would need for such a project are available in this volume. Thus, I can recommend this book highly to anyone with a natural but untutored penchant for collecting stones. You will find your enjoyment of this pastime much enhanced.

In this essay, I have used “stone” and “rock” as though they were interchangeable in usage, but one notes that the title of this book is indeed, “The Japanese Art of Stone Appreciation.” I would like to close with a poem by Naomi Wakan, a Gulf Island poet, that contemplates the distinction between rocks and stones. She, like the authors of this book, comes down resolutely on the side of “stone” when one is dealing with something to be aesthetically appreciated.

Are Rocks Stones?

Stones are quiet things

gathered on beaches

shifted about in pockets.

Stones are tumbled together

until, become gem-like they are viewed with awe.

Rocks are torn from moons

and other exotic places;

shredded in labs for what their innards might reveal.

Rocks are attacked with cleats

and picks and Vikings who seek

to conquer, or, as in the inevitable

cycle of things, themselves

be conquered in turn.

Stones are placed in courtyards

and gazed at patiently for years

until there are signs of growth.6

Sonja Arntzen

Footnote

1 Edward H. Schafer, Tu Wan’s Stone Catalogue of Cloudy Forest, University of California Press, 1961, p. 1.

2 Xiaoshan Yang, Metamophosis of the Private Sphere: Gardens and Objects in Tang-Song Poetry, Harvard University Press, 2003, p. 18.

3 Author’s translation, but I first found the poem in Yang’s Metamophosis of the Private Sphere, and followed Yang’s citation of the original Chinese on p. 101.

4 Katsu koori/ katsu wa kudakuru/ yamagawa no/ iwama ni musebu/ akatsuki no koe, poem no. 631 in the Shinkokinshu poetry anthlogy. (c. 1200)

5 Shizukasa ya/ iwa ni shimiiru/ semi no koe, from Basho’s Oku no hosomichi, “Narrow roads to the Back Country.” Basho composed this haiku on a visit to Ryushaku Temple in Yamagata province.

6 Poem by Naomi Wakan, from Gardening, Bevalia Press, 2007, p. 12. Reprinted with permission from the author.