Читать книгу Nine Rabbits - Virginia Zaharieva - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGnomes and Gardens

My grandmother was a good gardener, but the garden that Grandpa created on the acre around the house was magical. Our house was built in the new part of Nesebar near a forest, amidst huge sand dunes. It was finally my grandma’s own house and her own garden after so many years of trials and tribulations with six children in fureign houses in fureign lands. The garden thrived on the sand, and my grandfather worked his magic. Flowers and vegetables previously unknown in these parts appeared—and little clay gnomes! No one had even dreamed of garden gnomes back then. One was a hunter with a rifle and a rabbit in his hand; another gathered mushrooms in the basket on his back, which filled up when it rained. There was a lazy, mischievous, lounging one, as well as industrious gnomes with all sorts of tools thrown over their shoulders. Slightly shorter than me, they were my dolls; I fashioned clothes for them from flowers. I was convinced that mercury came from the droplets on the leaves of the watercress and velvet from the petals of the dahlia, and corn silk made fantastic coiffures.

In our garden, vegetable crops alternated with rows of flowers. Marigolds, tagetes, and nasturtiums separated the potatoes from the carrots and peppers. The herbs blanketed everything with fragrance: rosemary, celery, basil, dill, anise, coriander, lovage, mint, pennyroyal, marjoram, sage. At the very end of the garden, beyond the cucumbers and pumpkins, lived a family of turtles, whom I lulled to sleep in a cardboard box. Grandpa made the garden fence out of fresh poplar cuttings that took root. It didn’t take long before our garden was ringed by a thick wall of saplings. Boris set colorful, decorative gourds to creep up their trunks, which rattled in the wind and scared off the birds. Amidst the fruit trees, there was also a scarecrow with red wavy hair, which resembled Nikula when she was enraged. Besides the usual sorts of tomatoes, my grandfather was very proud of his orange tomatoes and yellow peppers; meaty and massive, they were brought from Hungary, but the seedless oxheart tomato with its delicate pinkish hues was still the most delicious.

For the first seven years of my life, I didn’t even know what a greengrocer was, or a telephone or television. Whenever we needed something, I was told to go and get some cabbage near the fence or some potatoes next to the nasturtiums. Somewhere around that time, I learned to eat hot peppers. When Grandpa sent me into the garden to pick some of his peppers for him, he told me to pluck one of the baby ones for myself, which were slightly spicy. I was the fussiest eater in the world. My grandma got it into her head that the only way to save me was for me to start eating spicy foods.

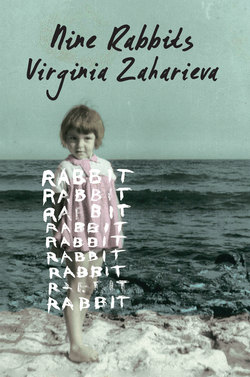

I was scrawny, baked by the sun, with long, dark hair down to my shoulders. I look like an Indian in photos from that period. I would wear white, sagging pants, and woolen socks, sewn by my grandma to the soles of old sneakers cut to fit my foot. These were pretty uncomfortable, because in the toe something like a sand bomb would form, with its own, independent trajectory. I had two dresses and one pair of shoes, which were saved for more dignified occasions. Most of the time, I tramped around barefoot.

It was poverty with a capital P. Aunt Maruna, after coming home and carefully putting away her school dress, would pull on some reworked skirt of Grandma’s, with no panties on underneath. Who’d buy you those extras? The dresses in the attic were not to be touched. When I wanted to get back at Maruna for something, I would wriggle under her skirt and lift it high over my head in front of the other kids or the workmen in the yard. Maruna would scream and chase me, until Grandma caught us and lifted us both up by the ears.

I didn’t have any toys, but as compensation, besides the gnomes, all the construction tools were at my disposal: pliers, an adz, a hammer, nails, lumber. With them, I crafted various contraptions. These undertakings led to my interest in building and to the creation of dozens of little houses, huts, and other dwellings. This proved to be an unenviable passion, since I seemed to be the only one gripped by it. Immediately after our initial rush of excitement to make a fort, the other kids’ enthusiasm would evaporate and I usually had to finish building it on my own. Afterward, however, I could never drag them out of what I’d just cobbled together from scraps of rugs. In the evening, they’d show up with potatoes and peppers, asking, “Why don’t we light a campfire? Why don’t we roast these and all live together in the little hut?”