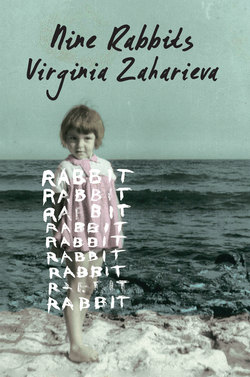

Читать книгу Nine Rabbits - Virginia Zaharieva - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDolphins and Lemon Cream

During the winter and in the early spring, when it was neither construction nor gardening season, my grandmother busied herself with my education. She put together a serious program of study, consisting of learning Czech from children’s books and practicing household skills, which, in her opinion, every girl ought to master. In the morning, I had two hours of Czech, with sewing lessons as a break. How to thread a needle, how to tie a knot, how to sew on a button, how to mend a sock, crocheting, backstitching, tacking, and hemming. The quick and dexterous washing of dishes was also a sort of wizardry unto itself—preparing the water, soaping, rinsing. Sweeping and washing the floor. Peeling potatoes, onions, and garlic. Cooking. Folding clothes. In spring I took part in hoeing the garden, weeding, planting the sprouts, reinforcing the greenhouses, painting, and spraying the fruit trees. As I made progress with my Czech and with my household and gardening skills, my grandmother’s gaze softened. She coddled me with pancakes and unlocked the cupboard with minty Lukche hard candies and Mu caramels. On these days, peace, coziness, and order ruled the house.

In the afternoon I was free to do as I pleased. In the evening, before going to bed, Nikula would stand in front of the mirror and put thick layers of lemon cream on her face. She didn’t have a single wrinkle. When she wasn’t reading Tolstoy, she would tell me fairy tales—she only knew two—about the fox who played dead and tossed the fish out of the cart, and the story about the goat who sang: Butchered, butchered, but not quite dead!

Grandma always slept on her back, stretched out like a board. She was warm, and her whole being exuded the scent of lemon. Surely somewhere in the labyrinths of her life that sweet morning sleep had left her, because at 4:30 every morning, Nikula was up and at it, ready for heroics. For starters, that meant running barefoot on the beach. All the energies are awake at that time and the sea gives off iodine fumes, or so she said. In early spring we slept out on the porch, to toughen up. Its walls were made of climbing plants that blossomed with tiny white flowers, but they couldn’t stop the sand, which flew in off the big dunes around the house. In the mornings when I awoke to the seagulls’ cries, sand crunched in my mouth. Before I knew what was happening, I was already following my grandmother down to the beach with chattering teeth, her sweater tossed over my shoulders. At that time of day, the surf was as gentle as a kitten. Even the sea felt like sleeping that early. From those jogs I clearly remember only the cold, her exquisite, tanned legs peeking out from beneath her gingham skirt, and the dead dolphins tossed up on the shore.

Now every morning I look at my legs, which are the same as hers, and wonder what to do with that furious urge to run and work from the early hours. But then I remember that I used to love sleeping in.

In the period of my early morning sprints with Nikula, the local fishermen often illegally bombed the fish with dynamite to kill more of them at once. The fish would float to the surface, torn apart or stunned, and ready to be gathered up. Such blasts would sometimes take out dolphins as well. There were a few spots where the beach cleaners would pile up the dead dolphins, and Rufi and I, plugging our noses, would go to watch them rotting away. Their skins mummified and lasted longest, black and hard, while the contents turned to white worms that eventually dried out, too.

A fish bomb killed Rufi’s father, and it was then that I saw a dead man for the first time. Since only the upper part of his body remained, in the coffin there was a soccer ball where his legs had been. Rufi claimed that his father was only pretending to be asleep, while I didn’t dare to breathe because of the room’s sweetish smell. I dashed outside and threw up.

After that, I stopped visiting the dolphin graveyard and forgot about death.