Читать книгу Nine Rabbits - Virginia Zaharieva - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDresses

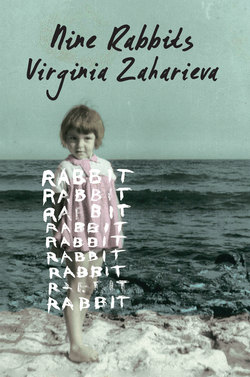

I turned up in the seaside town of Nesebar—an inconvenient four-year-old grandchild. My grandmother was raising the last two of her six children, putting the finishing touches on the house, ordering the workmen around, and doing some of the construction work herself. Thank God for this, as it used up some of her monstrous energy. Otherwise who knows what would’ve become of me.

Klement and Maruna, the runts of the litter, were rarely at home, since they went to boarding schools in Burgas. My aunt studied agriculture, while my uncle was at the nautical school.

Whenever I disappeared for long stretches somewhere inside the house, you could bet that I was in the attic, where there were a dozen big chests full of shoes, dresses, and all sorts of accessories brought from Czechoslovakia, where the family had prospered. Grandma Nikula and Grandpa Boris—“the Czechs,” as they were called—had worked in the glass factories of Bohemia between 1948 and 1958, during the most optimistic years of the Klement Gottwald regime.

Nikula’s father had been a cloth trader, so she had an eye for materials and colors. In Czechoslovakia she had sewn dresses for herself and her daughters and had even managed to marry off her oldest girl in Prague at the age of eighteen.

Nikula truly did dress with taste, although she only did so now when we went to the movies or when she stumped for the Communist Party’s Fatherland Front in the nearby villages.

She took me with her. Where could she leave me? I stood in front of the podium and watched her. When she got up in front of the masses, my grandmother was very beautiful and convincing. I was proud of her; she always managed to slip in something from her own heroic biography that made her speech entertaining. For example, when she was eight months pregnant with my uncle, she helped the brigades build the Hainboaz Pass in the Balkan Mountains and was a Shock-worker despite her huge belly.

Now, absorbed in building the house, she didn’t have the time or occasion to parade around in her dresses. So they all belonged to me.

The attic was plastered with a mixture of sheep manure, fine straw, and dark red clay. The scent of turds and dust accompanied my odysseys through 1950s fashion in front of a large cracked mirror, illuminated by the single skylight in the roof. First, I would put on a black satin slip with lace trim. Then I would add white silk petticoats. Next came the colorful flowered dresses—tailored at the waist, flared at the bottom. They either had straps, were backless, or had plunging necklines. Trembling, I would try them on one by one. The shoes had solid heels, open backs and another little opening at the tip of the toes. I climbed up onto the high heels and was beautiful. Dolled up like this, I would spend hours enraptured by the family treasures. Once I even found a pistol. I showed it to Rufi, my friend from next door, and then hid it again in a different spot. Grandma and Grandpa fought a lot, and I was afraid that they’d end up shooting each other some evening.

I shared the attic with giant nesting seagulls who yielded their territory to me with a squawk. At that time I hadn’t yet seen Hitchcock’s The Birds, so I studied the eggs in the nest without a thought for the mother lurking outside. During some important surveillance mission, I would hear my grandma’s raspy voice: “Where are you, girl? Saraaa, Pepaaa, Marunaaa, Klemooo, Ivaaan, Veraaa!” Once she finished reeling off her children’s names, completely furious, she’d hit upon my name and bark, “Mandaaaa, I’mgonnatearoutyourhair, get down from there this instaaaant!” Sometimes I thought my name was I’mgonnatearoutyourhair. “How many times have I told you not to rummage around in the attic?”

Her voice echoed through the shaft leading up to the attic. It was a difficult place to climb up to. I counted on this while hiding among the chests, but sometimes she was so mad that she’d climb up the ladder, huffing and puffing. A wild chase around the rafters would ensue; “You little turd,” and “Brat” were her war cries. At first it was fun, but the fun soon ended. She would beat me with whatever was at hand—a belt, a hanger, an umbrella—and then she’d collapse, exhausted, onto some heap of clothing while I quickly escaped. I would come back late, hoping she would be asleep, but she would be lurking by the door to smack me again: this time for good-night.